born: Giuseppe Balsamo

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

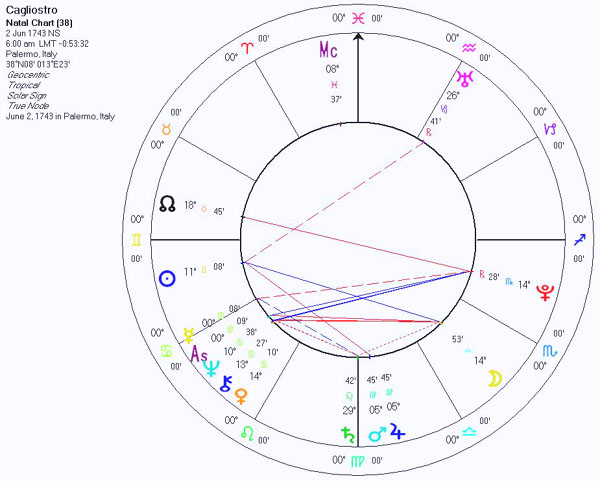

June 2, 1743 in Palermo, Italy

TO BE REWORKED

Alessandro, Count di Cagliostro

1743-1795born Giuseppe Balsamo on June 2, 1743 in Palermo, Italy.

Early in Cagliostro's life his father died and because his mother was unable to support him, he was sent to live with his uncle until he ran away after which he was sent to a seminary and he again ran away. Finally Cagliostro was sent to a Benedictine monatery, where he discovered a talent for medicine and chemistry. Although he was a very good student he tried to look beyond the basic information he was given . After several years Cagliostro once again ran away from the monastery joining a band of 'vagabonds', that committed petty crimes as well as murders. Constantly in police custody thanks to his association with the vagabonds, it was only thanks to his uncle that he wasn't sent to prison for his crimes. As quickly as he had become involved with the vagabonds, when at the age of seventeen he began to feign interest in the occult and alchemy when a goldsmith named Marano arrived in Palermo and became associated with Cagliostro.

Marano met with many alchemists who had claimed to be able to transmute metals, but he believed that Cagliostro alone had the power to do so. Seeing that Marano believed in him, Cagliostro asked for sixty ounces of gold (a very large sum, considering that one ounce costs nearly $300 today 9/99) to conduct magical ceremonies and then would show Marano the location of a large cache of treasure hidden near the city. With some hesitation Marano gave Cagliostro the gold and at midnight that night he was led to the field some distance from Palermo. The only thing awaiting Marano were some thugs Cagliostro had hired to attack him. Soon after, Cagliostro fled Palermo and began his world travels.

Cagliostro traveled throughout the world, visiting Egypt, Greece, Persia, Rhodes, India and Ethiopia, studying the occult and alchemical knowledge he found in those countries. In 1768 Cagliostro returned to Italy first going to Naples, where he met one of the thugs who helped him attack Marano. The two men went to Naples and opened a Casino, to cheat wealthy foreigners out of money. Neapolitan authorities quickly discovered their plot and forced the men to leave. Cagliostro went to Rome where established himself as doctor, making a very good living. While in Rome, he met and married Lorenza Feliciani, called Serafina. The couple lived in Rome until members of the Inquisition began to suspect Cagliostro of heresy. Quickly they both went to Spain, where they spent several years and then returned to Cagliostro's home town of Palermo, where he was arrested by Marano. Cagliostro was saved by a nobleman, and after cheating an alchemist out of 100,000 crowns (about $1 million) the man and wife went to England in the 1760's, claiming to have discovered an alchemical secret.

Cagliostro met the Comte de Saint-Germain in London, who initiated him into the rites of Egyptian Freemasonry, as well as the recipes for the elixirs of Youth and Immortality. After establishing Egyptian Rite Masonic Lodges in England, Germany, Russia and in France Cagliostro went to Paris in 1772, where he again sold medicines, elixirs and began to hold séances. King Louis XVI became interested in Cagliostro, and was entertained by the Count who held magic suppers to entertain the court at Versailles. For many years Cagliostro was a favorite of the French court, until 1785 when he was involved in the Affair of the Necklace, one of the major events that led to the French Revolution in 1789. Thanks to his involvement in the scandal, Cagliostro spent six months in the Bastille and then was banished from France.

Cagliostro went to Rome with his wife in late 1789, taking up the practice of medicine and séances once more. All went well for several years until he attempted to found a Masonic Lodge in Rome, after which the Inquisition arrested him in 1791, imprisoned him in the Castle of Saint Angelo (originally the tomb of Roman Emperor Hadrian in ancient times) in Rome and held a trial, accusing him of heresy, magic, conjury, and Freemasonry. After eighteen months of deliberations, the Inquisition sentenced Cagliostro to death but his sentence was changed by the Pope to life imprisonment in the Castle of Saint Angelo. Cagliostro attempted to escape, but was easily overpowered. Then, he was sent to the solitary castle of San Leo near the city of Montefeltro, one of the strongest castles in Europe, where he died on August 26, 1795. The reports of Cagliostro's death were not believed throughout Europe and only after a report commissioned by Napoléon did people accept the fact Cagliostro was actually dead.

Cagliostro is said to be one of the greatest figures in occult, although since the late 19th century he has been considered by many to be a charlatan. Many wild stories have grown up around him, which have obscured the true facts of his life, which are more unbelievable than the fiction.

see Francis Rakoczy biographical

From a Theosophical website: CAGLIOSTRO

FOR 150 years Alessandro Cagliostro has been defamed as the arch-impostor of the eighteenth century. Why? Because it is claimed that Cagliostro was one of the many aliases assumed by the notorious adventurer Giuseppe Balsamo. This claim is based, first, upon the lies of Theveneau de Morande, a French spy and blackmailer who, in the words of a brilliant study by M. Paul Robiquet, was "from the day of his birth to the day of his death utterly without scruple"; and, second, upon a Life of Balsamo published anonymously in 1791 under the auspices of the Inquisition.

In 1890 H. P. Blavatsky boldly took issue with these two "authorities" by declaring that "whoever Cagliostro's parents may have been, their name was not Balsamo." In 1910 W. R. H. Trowbridge, in his book on Cagliostro, asserted that the statement that Cagliostro and Balsamo were the same person "would appear to be directly contrary to recorded fact." As Cagliostro gave out his own story through his advocate, Thirolier, common justice demands that some attention be paid to his words.

In these Memoirs, Cagliostro frankly admitted that he knew neither the name of his parents nor the place of his birth. He had been told that his parents were Christians of noble birth who had left him an orphan at the age of three months. He believed that he had been born on the Island of Malta. His earliest recollections took him back to the holy city of Medina in Arabia, where he was called Acharat and where he lived in the palace of the Muphti Salahaym. Four persons were attached to his service, the chief of whom was an Eastern Adept named Althotas who instructed him in the various sciences and made him proficient in several Oriental languages. Although both teacher and pupil outwardly conformed to the religion of Islam, Cagliostro later wrote, "the true religion was imprinted in our hearts."

When the boy was twelve years old, he and Althotas began their travels. The first stopping place was Mecca, where they lived for three years in the palace of the Cherif. On the day of their departure the aged Cherif pressed the boy to his bosom and exclaimed: "Nature's unfortunate child, adieu!"

In Egypt they "inspected those celebrated Pyramids which to the eye of the superficial observer appear as enormous masses of granite," but which, to the Adept-eye of Althotas, were holy fanes of initiation. Certain Temple-priests of that ancient land took the boy into "such palaces as no ordinary traveller has ever entered before." Finally, after wandering through Asia and Africa for three years, the two reached the Island of Malta, where they were entertained in the palace of Pinto, Grand Master of the Knights of Malta. There Althotas donned the insignia of the Order, and the young wanderer assumed European dress for the first time and received from his teacher the name of Cagliostro.

Althotas died in Malta, and Cagliostro, accompanied by the Chevalier d'Acquino, then visited Sicily and the Isles of Greece, stopped for a while in Naples, and finally reached Rome, where he made the acquaintance of Cardinal Orsini and the Pope. It was in Rome, when Cagliostro was twenty-two years old, that he met and married Lorenza Feliciani, who proved to be a tool of the Jesuits and the chief cause of his troubles.

In 1776 the Count and Countess Cagliostro were occupying apartments in Whitcombe Street, Leicester Fields, London. Cagliostro, now a man of twenty-eight, spent most of his time in his chemical laboratory, while his attractive wife amused herself with her new-found friends. Cagliostro's extreme good nature and the blind confidence which he placed in his friends made him their easy victim, and when he left London eighteen months later he sadly confessed that they had swindled him of 3,000 guineas.

On April 12, 1777, Cagliostro became a Freemason. His life in Egypt, his association with the Temple-priests, and his probable initiation into some of the Egyptian mysteries had fired him with a determination to found an Egyptian Rite in Masonry based upon these Mysteries, the aim of which was the moral and spiritual regeneration of mankind. The Masonic authority, Kenneth Mackenzie, says:

His system of Masonry was not founded on shadows. Many of the doctrines he enunciated may be found in the Book of the Dead and other important documents of ancient Egypt. And though he may have committed the fatal error of matching himself with the policy of Rome and getting the worst of it, I have not yet been able to find one iota of evidence that he was guilty of anything more reprehensible than an error of judgment during his various journeys. (Royal Masonic Cyclopaedia, p. 100.)

Baron von Gleichen, a man of irreproachable integrity and wide experience, declared that "Cagliostro's Egyptian Masonry was worth the lot of them, for he tried to render it not only more wonderful, but more honorable than any other Masonic Order in Europe."

Although Cagliostro's Egyptian Rite was open to both sexes, his was by no means the first attempt to give women a standing in Masonry. The Grand Orient of France established a "Rite of Adoption" in 1774. The Duchesse de Bourbon was Grand Mistress of the Rite in 1775, and in 1805 the Empress Josephine acted in the same capacity.

Cagliostro made his first speech on Egyptian Masonry in The Hague, where a Lodge was formed in accordance with the Rite. In Nürnberg, when Cagliostro was asked for his secret sign, he replied by drawing the picture of a serpent biting its own tail. This symbol was the "Circle of Necessity" of the ancient Egyptians, and it is also found on the seal of the Theosophical Society. After establishing his Egyptian Rite in other German cities, Cagliostro arrived in Mittau, capital of the Duchy of Courland, in March 1779. The Masonic Lodge in Mittau was composed principally of noblemen, most of whom were interested in some branch of the occult sciences. The head of this Lodge, the Marshal von Medem, had been a student of alchemy from his early youth, and he welcomed his new brother with open arms. Cagliostro was immediately invited to give an exhibition of his occult powers. He refused, declaring that such powers should never be displayed for the gratification of idle curiosity. Later, after much persuasion, he consented. As a result, some of his new friends began to look upon him as a supernatural being, while others denounced him as a charlatan.

Cagliostro then proceeded to St. Petersburg, where he appeared for the first time as a magnetic healer. In May, 1780, he arrived in Warsaw, then a great stronghold of both Masonry and Occultism. There he was entertained by Prince Poninski, whose initiation into the Egyptian Rite gained the adherence of a large number of the Polish nobility. The King of Poland heard of Cagliostro's occult powers through a prediction he made to a young lady of the Court. "I do not know," writes Laborde, "what confidence the King and the young lady placed in these predictions, but I do know that they were all fulfilled."

In September, 1780, Cagliostro reached Strasbourg, the capital of Alsace. On the morning of his arrival crowds of people gathered on both banks of the Rhine to catch a glimpse of the mysterious stranger whose fame as a magnetic healer and friend of humanity had preceded him. From the day of his arrival in Strasbourg Cagliostro gave up his entire time to altruistic service. No sick or needy person appealed to him in vain. Every day he visited the unfortunate, whose distress he relieved not only with money, but, as Baron von Gleichen says, "with manifestations of a sympathy that went to the hearts of the sufferers and doubled the value of the actions." He refused all compensation for his services, and if a present were given to him, he repaid it with a counter present of double value. He supported his poor patients for months at a time, often lodging them in his own house and feeding them at his own table. Like Mesmer, Cagliostro treated his patients magnetically, applying the force directly without the aid of magnetized objects. When he left Strasbourg 15,000 people claimed to have been helped by him.

Shortly after Cagliostro's arrival in Strasbourg he was summoned to the palace of the Prince Cardinal de Rohan, who was deeply interested in the occult sciences and possessed one of the finest alchemical libraries in Europe. When Cagliostro was invited to live in the Cardinal's palace, malicious tongues began to wag, and the rumor spread that His Holiness was spending a fortune upon his new friend. The Baronesse d'Oberkirch repeated the gossip to the Cardinal, who vehemently asserted that "Cagliostro is a most extraordinary, a most sublime man, whose knowledge is equalled only by his goodness. What alms he gives! What good he does! I can assure you that he has never asked for nor received anything from me!"

After leaving Strasbourg, Cagliostro went to Bordeaux and Lyons, where Saint-Martin had formerly lived. These cities welcomed him as a new prophet, and many influential men and women were initiated into his Egyptian Rite. In Lyons his Rite was so highly acclaimed that a special Temple was built for its observance, which later became the Mother Lodge of Egyptian Masonry.

Cagliostro settled in Paris in 1785, and his house on the Rue St. Claude became the talk of the town. The entrance hall was adorned with a black marble slab upon which was engraved Pope's Universal Prayer. Statuettes of Isis, Anubis and Apis stood along the walls, which were covered with Egyptian hieroglyphics, and the two lackeys were clothed like Egyptian slaves as they appear on the monuments of Thebes. Cagliostro received his guests in a black silk robe and an Arabian turban made of cloth of gold and sparkling with jewels. He had a striking countenance with "eyes of fire which burned to the bottom of the soul." Cardinal de Rohan confessed that when he first saw Cagliostro he found a dignity so imposing that he was penetrated with awe. According to Georgel, Cagliostro "lived in the greatest affluence, giving much to the needy and seeking no favors from the rich," although no one seemed to know the source of his income. His friends addressed him as "Grand Master," and busts of le divin Cagliostro adorned the salons of his admirers.

Shortly after Cagliostro's arrival in Paris he was invited to membership in the Philalethès, a Rite founded in 1773 in the Loge des Amis Réunis. The Mother Lodge was a Theosophical organization founded by Savalette des Langes, whose manuscripts, after his death, passed to the Philosophical Scottish Rite. Cagliostro joined the Philalethians hoping to infuse some Theosophical principles into their Rite. There are many landmarks in Cagliostro's biographies showing that he taught the doctrine of the "principles" in man and the presence of the indwelling God, and there seems to be no doubt that he served the Masters of a Fraternity he would not -- could not -- name. This fact is admitted by Kenneth Mackenzie:

It is a rule recognized amongst adepts -- in fact, a stringent obligation -- that they shall not reveal the identity of their preceptors and initiators; and if that rule was applicable in times before Cagliostro, so it was in his own time. He was sent, in accordance with occult discipline, to rove about Europe, and we have before seen him under the protection of the Knights and Order of Malta; he completes his course by going to Paris and London, and there he was initiated into Masonry. (Royal Masonic Cyclopaedia, p. 99.)

In Cagliostro's letter to the Philalethians he assured them that the "unknown Grand Master of true Masonry" had cast his eyes upon them, as he wished to prove to them "the original dignity of man, his powers and destiny . . . of which true Masonry gives the symbols and indicates the real road." When the Philalethians refused his help, Cagliostro replied: "We have offered you the truth; you have disdained it. We have offered it for the sake of itself, and you have refused it in consequence of your love of forms." Cagliostro's own Egyptian Rite, however, flourished from the moment he reached Paris. One of the first persons to be initiated was the young Marquis de Lafayette, already a high Mason and the leader of the pre-Revolutionary period in France. Cagliostro also acted as delegate to the two great Masonic conventions which took place in Wilhelmsbad and Paris in 1782 and 1785.

On August 23, 1785, Cagliostro was accused of complicity in the "Diamond Necklace Affair" and sent to the Bastille. After being imprisoned for nine months he was honorably acquitted, but at the same time (as the Queen was implicated in the scandal) he was asked to leave France. Upon his arrival in England he was accused by the French spy Morande of being the notorious Giuseppe Balsamo. Cagliostro refuted Morande's accusation in an Open Letter to the English People. Morande was forced to retract his statements and apologize to his readers. Nevertheless for the past 150 years historians have continued to confound Cagliostro with Giuseppe Balsamo.

Broken-hearted by the loss of his good name, Cagliostro left England. After years of wandering he arrived in Rome in the spring of 1789. Making one last desperate effort to revive his Egyptian Rite, he was prevailed upon to initiate two men, who proved to be spies of the Inquisition. On the evening of December 27, 1789, he was arrested and thrown into a dungeon in the Castle of St. Angelo. Shortly afterward he was sentenced to death, the sole charge against him being that he was a Mason, and therefore engaged in unlawful studies. As an instance of the hatred of the Papal government for Freemasonry, part of Cagliostro's sentence, issued on March 21, 1791, is worth quoting:

Giuseppe Balsamo, convicted of many crimes, and of having incurred the censures and penalties pronounced against heretics, has been found guilty and condemned to the said censures and penalties as decreed by the Apostolic laws of Clement XII and Benedict XIV, against all persons who in any manner whatever favor or form societies and conventicles of Freemasonry, as well as by the edict of the Council of State against all persons convicted of this crime in Rome or in any other place in the dominions of the Pope.

During his imprisonment Cagliostro's private papers, family relics, diplomas from foreign Courts, his Masonic regalia and even his manuscript on Egyptian Masonry were publicly burned in the Piazza della Minerva. While the condemned Occultist was awaiting his fate, a mysterious stranger demanded an audience with the Pope. He was received, and immediately thereafter Cagliostro's death sentence was changed to life imprisonment in the Castle of St. Leo, located on the frontiers of Tuscany. This Castle stands on the summit of an enormous rock with almost perpendicular sides. Cagliostro was pulled up the side of the mountain in a basket and incarcerated in a dungeon. Here he languished for three years, writing a sentence every day on the walls of his living tomb. The last entry bears the date of March 6, 1795. Exactly seven months later, on October 6, the Paris Moniteur contained a small paragraph announcing that "it is reported in Rome that the famous Cagliostro is dead."

If this statement was true, and Cagliostro actually did die in the Castle of St. Leo, why are tourists shown the little square hole in the Castle of St. Angelo in Rome where he is said to have expired? After his supposed death it was whispered that Cagliostro had escaped from his dungeon in some miraculous manner, thus forcing his jailers to spread the news of his death. H.P.B. says that "having made a series of mistakes, more or less fatal, he was recalled." His downfall, she declared, was due to his weakness for an unworthy woman and to his possession of certain secrets of nature which he refused to divulge to the Church.

A century and a half have passed since then, and modern Masons, although describing Cagliostro as "a Masonic martyr" (a change of heart due principally, it seems, to the influence of Trowbridge's book), also write of him as a "medium" who perhaps resorted to trickery and employed the devices of a mountebank. (See The New Age, XXVII, Nos. 5 and 6.) How long will thoughtless people continue to defame the good names of the living and mar the memory of the dead by repeating slanders and calumnies? H.P.B. declared that Cagliostro's justification must take place in this century -- a task in which Theosophists can do their part.