Helena P. Blavatsky

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

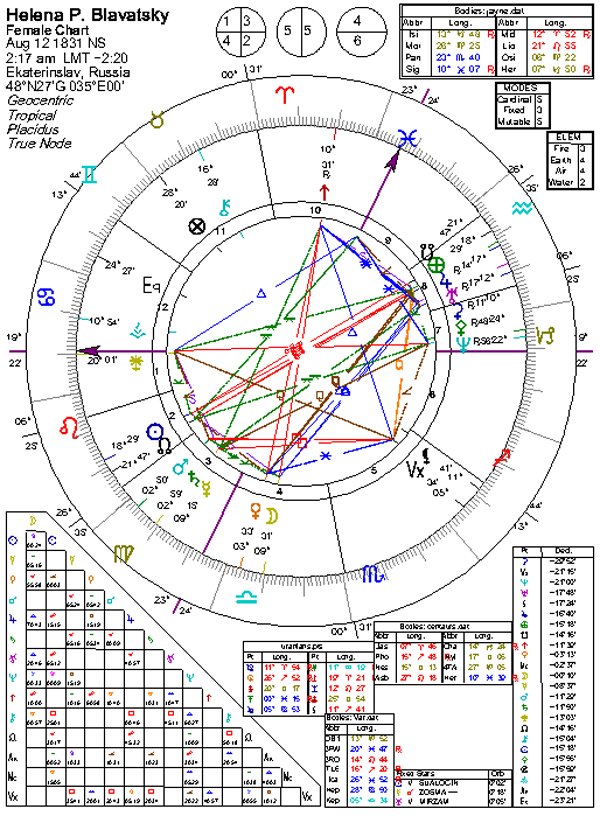

Helena P. Blavatsky - Theosophist, Occultist, Founder of the Theosophical Society: August 12, 1831, Ekaterinoslav, Russia. Time rectified variously as 2:17 AM, 2:33 AM (Davison), 1:56:56 AM and 4:38 AM, and even 00:10 AM. Died, May 8, 1891, London, England.

(Sun, Cancer; Leo; Ascendant; Moon conjunct Venus, Libra; Mars, Saturn, Mercury conjunct in Virgo; Jupiter conjunct Uranus, Aquarius; Neptune, Capricorn; Pluto, Aries).

Bringing the Theosophical Society to birth was a function of her Cancerian energy and the germinating energy of Virgo. Madame Blavatsky needed the great authoritative strength of Leo to carry out her mission. She had to stand as a “tower of strength” against the virulent and ignorant religious and scientific orthodoxy of her day. A keenly discriminating and practical mind bestowed by the Virgo energy was also a necessity for her work. Bringing the Theosophical Society to birth was a function of her Cancerian energy. She also had to act, not only as an exemplar (Leo) of the Ageless Wisdom, but as a defender (Cancer) of the Ageless Wisdom Tradition against all defamers.

Knowledge increases in proportion to its use; that is, the more we teach the more we learn.

To act and act wisely when the time for action comes, to wait and wait patiently when it is time for repose, put man in accord with the rising and falling tides (of affairs), so that with nature and law at his back, and truth and beneficence as his beacon light, he may accomplish wonders. Ignorance of this law results in periods of unreasoning enthusiasm on the one hand, and depression on the other. Man thus becomes the victim of the tides when he should be their Master.

Be humble, if thou would'st attain to Wisdom. Be humbler still, when Wisdom thou hast mastered.

The Path that leadeth on is lighted by one fire - the light of daring burning in the heart. The more one dares, the more he shall obtain.

We cut these numerous windings in our destinies daily with our own hands, while we imagine that we are pursuing a track on the royal high road of respectability and duty, and then complain of those ways being so intricate and so dark. We stand bewildered before the mystery of our own making, and the riddles of life that we will not solve, and then accuse the great Sphinx of devouring us."

To act and act wisely when the time for action comes, to wait and wait patiently when it is time for repose, put man in accord with the rising and falling tides (of affairs), so that with nature and law at his back, and truth and beneficence as his beacon light, he may accomplish wonders. Ignorance of this law results in periods of unreasoning enthusiasm on the one hand, and depression on the other. Man thus becomes the victim of the tides when he should be their Master.

Our prayers and supplications are vain, unless to potential words we add potent acts, and make the aura which surrounds each one of us so pure and divine that the God within us may act outwardly, or in other words, become as it were an extraneous Potency. Thus have Initiates, Saints and very holy and pure men been enabled to help others as well as themselves in the hour of need, and produce what are foolishly called 'miracles,' each by the help and with the aid of the God within himself, which he alone has enabled to act on the outward plane.

H.P. Blavatsky Coll. Wr. Vol. XII, p.533-34No Entity, whether angelic or human,

can reach the state of Nirvana,

or of absolute purity, except through aeons of suffering and the knowledge of EVIL

as well as of good,

as otherwise the latter remains incomprehensible.

Secret Doctrine 2, p. 81"Error runs down an inclined plane,

while the Truth has to laboriously climb its way up hill."

Old truisms are often the wisest.

The human mind can hardly remain entirely free from bias, and decisive opinions are often formed before a thorough examination of a subject from all its aspects has been made.

Secret Doctrine 1, p. XVIIThe true philosopher, the student of the Esoteric Wisdom, entirely loses sight of personalities, dogmatic beliefs and special religions.

Secret Doctrine 1, p. XX[H.P. Blavatsky to Emilie de Morsier about herself]

Nothing can make me falter on the path, once I have started on a journey. Do you want to know why? Because some twenty years ago I had lost faith in humanity as individuals, and love it collectively, and work universally instead of working for it individually. To do so I have my own way. I do not believe any longer in perfection; I do not believe any longer in infallibility, nor in immaculate characters.

Each of us is a piece of charcoal, more or less black and, excuse me, stinking. But there is hardly any piece so vile and dirty that it has not atoms wherein lie the germ of a future diamond. And I keep my eyes fixed on these atoms, and do not see the rest, and do not want to see. As I work for others and not for myself, I permit myself to use these atoms for the common cause. Thus I do not see, nor did I see, in Mr. Fortin anything but his talents and his practical ability for the demonstration of truth.... I do not see why, were he a thousand times worse than he is, I could not use him for the common cause, the good of humanity in general

... Everything has its good and its bad side. Let us take the good and use only that which is useful, and let us leave what is bad to break its own neck.

Cranston, p. 242,243Men and parties, sects and schools are but the mere ephemera of the world's day.

TRUTH, high-seated upon its rock of adamant,

is alone eternal and supreme.

H.P. Blavatsky, Isis Unveiled 1, p. VThere is a road, steep and thorny, beset with perils of every kind,

but yet a road, and it leads to the very heart of the Universe:

I can tell you how to find those who will show you the secret gateway that opens inward only,

and closes fast behind the neophyte for evermore.There is no danger that dauntless courage cannot conquer;

there is no trial that spotless purity cannot pass through;

there is no difficulty that strong intellect cannot surmount.

For those who win onwards there is a reward past all telling

- the power to bless and save humanity;

for those who fail, there are other lives in which success may come.

H.P. Blavatsky Col. Wr. XIII, p. 219the same question stands open from the days of Socrates and Pilate down to our own age of wholesale negation: is there such a thing as absolute truth in the hands of any one party or man? Reason answers, "there cannot be." There is no room for absolute truth upon any subject whatsoever, in a world as finite and conditioned as man is himself. But there are relative truths, and we have to make the best we can of them.

H.P. Blavatsky, Lucifer, February, 1888.The tree is known by its fruits; and as all Theosophists have to be judged by their deeds and not by what they write or say, so all Theosophical books must be accepted on their merits, and not according to any claim to authority which they may put forward.

H.P. Blavatsky, Key to Theosophy, p. 300But let each burning human tear drop on thy heart and there remain, nor ever brush it off, until the pain that caused it is removed.

H.P. Blavatsky, Voice of the SilenceWith every effort of will toward purification and unity with that `Self-god,' one of the lower rays breaks and the spiritual entity of man is drawn higher and ever higher to the ray that supercedes the first, until, from ray to ray, the inner man is drawn into the one and highest beam of the Parent-Sun.

H.P.Blavatsky, S.D. I-639"To seek to achieve political reforms before we have effected a reform in human nature, is like putting new wine into old bottles. Make men feel and recognize in their innermost hearts what is their real, true duty to all men, and every old abuse of power, every iniquitous law in the national policy, based on human, social or political selfishness, will disappear of itself . . . ."

H.P. BlavatskyThe whole difficulty springs from the common tendency to draw conclusions from insufficient premises, and play the oracle before ridding oneself of that most stupefying of all psychic anesthetics - IGNORANCE.

H.P. Blavatsky, Lucifer, October, 1888

Helena BlavatskyHelena Petrovna Hahn (also Hélène) (July 31, 1831 (O.S.) (August 12, 1831 (N.S.)) - May 8, 1891 London), better known as Helena Blavatsky or Madame Blavatsky, born Helena von Hahn, was a founder of the Theosophical Society.

Early years

She was born in the house of her mother's parents in Ekaterinoslav (now Dnipropetrovsk), Ukraine (then part of the Russian Empire). Her parents were Col. Peter von Hahn, a German officer in Russian service, and Helena Andreyevna Fadeyeva. Her mother belonged to an old Russian noble family and was the author, under the pen-name Zenaida R, of a dozen novels. Described by Belinsky as the "Russian George Sand", she died at the age of 28, when Helena was eleven.Upon his wife's death, Peter, being in the armed forces and realizing that army camps were unsuitable for little girls, sent Helena and her brother to live with her maternal grandparents. They were Andrey Fadeyev (at that time the Civil Governor of Saratov) and his wife Princess Helene Dolgoruki (see talk), of the Dolgorukov family and an amateur botanist. She was cared for by servants who believed in the many superstitions of Old Russia and apparently encouraged her to believe she had supernatural powers at a very early age. Her grandparents lived in feudal state, with never less than fifty servants.

First marriage

She married three weeks before she turned seventeen, on July 7, 1848, to the forty-year old Nikifor (also Nicephor) Vassilievitch Blavatsky, vice-governor of Erivan. After three unhappy months, she took a horse, and escaped back over the mountains to her grandfather in Tiflis. Her grandfather shipped her off immediately to her father who was retired and living near Saint Petersburg. He travelled two thousand miles to meet her at Odessa, but she wasn't there. She had missed the steamer, and sailed away with the skipper of an English bark bound for Constantinople. According to her account, they never consummated their marriage, and she remained a virgin her entire life. (For a counter-claim, see the section on Agardi Metrovitch.)Wandering years

According to her own story as told to a later biographer, she spent the years 1848 to 1858 traveling the world, claiming to have visited Egypt, France, Quebec, England, South America, Germany, Mexico, India, Greece and especially Tibet to study for two years with the men she called Brothers. She returned to Russia in 1858 and went first to see her sister Vera, a young widow living in Rugodevo, a village which she had inherited from her husband.Agardi Metrovitch

About this time, she met and left with Italian opera singer Agardi Metrovich.Some sources say that she had several extramarital affairs, became pregnant, and bore a deformed child, Yuri, whom she loved dearly. She wrote that Yuri was a child of her friends the Metroviches (C.W.I p. xlvi-ii, HPB TO APS p. 147). To balance this statement, Count Witte, her first cousin on her mother's side, stated in his Memoirs (as quoted by G. Williams), that her father read aloud a letter in which Metrovich signed himself as "your affectionate grandson". This is evidence that Metrovich considered himself Helena's husband at this point. Yuri died at the age of five, and Helena said that she ceased to believe in the Russian Orthodox God at this point.

Two different versions of how Agardi died are extant. In one, G. Williams states that Agardi had been taken sick with a fever and delirium in Ramleh, and that he died in bed April 19, 1870. In the second version, while bound for Cairo on a boat, the 'Evmonia', in 1871, an explosion claimed Agardi’s life, but H.P. Blavatsky continued on to Cairo herself.

While in Cairo she formed the Societe Spirite for occult phenomena with Emma Cutting (later Emma Coulomb), which closed after dissatisfied customers complained of fraudulent activities.

To New York

It was in 1873 that she emigrated to New York City. Impressing people with her psychic abilities she was spurred on to continue her mediumship. Throughout her career she was able to perform physical and mental psychic feats which included levitation, clairvoyance, out-of-body projection, telepathy, and clairaudience. One new feat of hers was materialization, that is, producing physical objects out of nothing. Though she was apparently quite adept at these feats, she claimed that her interests were more in the area of theory and laws of how they work rather than performing them herself.In 1874 at the farm of the Eddy Brothers, Helena met Henry Steel Olcott, a lawyer, agricultural expert, and journalist who covered the Spiritualist phenomena. Soon they were living together in the "Lamasery" (alternate spelling: "Lamastery") where her work Isis Unveiled was created.

She married her second husband, Michael C. Betanelly on April 3, 1875 in New York City. She maintained that this marriage was not consummated either. She separated from Betanelly after a few months, and their divorce was legalized on May 25, 1878. On July 8, 1878, she became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

Founds Theosophical Society

While living in New York City, she founded the Theosophical Society in September 1875, with Henry Steel Olcott, William Quan Judge and others. Madame Blavatsky claimed that all religions were both true in their inner teachings and false or imperfect in their external conventional manifestations. Imperfect men attempting to translate the divine knowledge had corrupted it in the translation. Her claim that esoteric spiritual knowledge is consistent with new science may be considered to be the first instance of what is now called New Age thinking. In fact, many researchers feel that much of New Age thought started with Blavatsky.To India

She had moved to India, sometime before 1879, where she first made the acquaintaince of A P Sinnett. In his book Occult World he describes how she stayed at his home in Allahabad for six weeks that year, and again the following year.[1]By 1882 the Theosophical Society became an international organization, and it was at this time that she moved the headquarters to Adyar near Madras, India.

The society headquartered here for some time, but she later went to Germany for a while and finally to England.

A disciple put her up in her own house in England and it was here that she lived the end of her life.

Death

Her last words in regard to her work were: "Keep the link unbroken! Do not let my last incarnation be a failure."Suffering from heart disease, rheumatism, Bright's disease of the kidneys, and complications from influenza, Madame Helena Petrovna Blavatsky died at the home she shared, in England on May 8, 1891. Her body was then cremated; one third of her ashes were sent to Europe, one third with William Quan Judge to the United States, and one third to India where her ashes were scattered in the Ganges River. May 8 is celebrated by Theosophists, and it is called White Lotus Day.

She was succeeded as head of one branch of the Theosophical Society, by her protege, Annie Besant. Her friend, WQ Judge, headed the American Section.

She was born of Russian nobility and later became the secretary of the Theosophical Society. Also, she was referred to as HPB. She did much to spread Eastern religious, philosophical and occult concepts throughout the Western world.

Her father Peter von Hahn was in the Russian army. Shortly after he married Helena Andreyevna he was called into war and his wife returned to her parent' home when their daughter Helena was born. Helena Andreyevna wrote novels concerning restricted Russian women and was called the George Sand of Russia.

She died when Helena was twelve, but later Helena would say that her mother had died when she was a baby. The question is why did Helena Blavatsky deny the existence of her mother in her childhood. It is true that she grew from a sickly baby into a problem child subjected to hysteria and convulsions. When dying her mother observed sadly, "Ah well, perhaps it is best that I am dying, so at least I shall be spared seeing what befalls Helena. Of one thing I am certain, her life will not be that of other women, and she will have much to suffer."

This statement that her mother died when she was a baby seems to suggest that there was strife between the mother and daughter. It indicates a conflict between the wills. That Helen resented her mother's long absences, her intimate friendships in the bohemian world of letters, and felt it as a desertion of the home and herself. Her mother seemed to have hurt her pride.

Helena's childhood was not the usual one. She displayed neurotic behavior from almost infancy by walking and talking in her sleep at four, exhibiting morbid tendencies, and loving the weird and fantastic. One of her earliest recollections was macabre in nature. At Ekaterinoslav, the countryside was said to be haunted with russalkas, green-haired nymphs living in willow trees along the river banks. Whenever her nurses crossed her Helena threaten to have the russalkas tickle them to death. One day when Helena was four she was walking by the river bank with one of her nurses while a serf-boy of fourteen followed them and annoyed Helena by pulling her perambutor. She them imitated one of her father's roars threatening to have the russalkas tickle the boy to death. The boy being scarred, took to his heels over the river bank. He was not seen again until fishermen discovered his dead body weeks later. Helena's family supposed he had accidentally stepped into a sand-pit whirlpool. But, the household surfs knew otherwise; they knew that the four-year-old girl had withdrawn her protection from the boy and delivered him over to the russalkas. It is significant that HPB should later accuse herself of homicide at the age of four, and the victim a boy ten years her senior.

Her memory of this incident is not surprising when view in perspective with other incidents of her childhood. Those who took care of her, besides her parents, were serfs and women who had learned and believed in superstitions. At the time Old Russia was a hothouse for superstitions. It was alive with tales of wolves, monsters, ghosts, leshes, brownies and goblins which were thought to manipulate human lives.. Even though the educated people accepted Russian Orthodoxy, along with its icons filling every room, priests and sacraments, their serfs still kept alive the Empire's pagan religion among themselves. The nurses of Helena, or Lelinka as they affectionately called her, believed these superstitions. Furthermore, Lelinka, being born in the seventh month of the year, was called a sedmitchka, a word that is difficult to translate but is connected with the number seven.

According to legend it was believed that supernatural beings could be placated or even controlled by people like Helena. On the night of her birthday the servants would carry the little girl around the house and stables while sprinkling holy water and repeating magical incantations to appease the domovoy, a goblin in the form of an old man who lived behind the stove and played tricks whenever displeased. Some thought each household had one. Supposedly such activities were not known by her mother or grandparents. If they did know about them, initially they refused to assign any importance to them until later.

It was not that the household servants thought that Helena was special, she showed it. She threw temper tantrums whenever she did not get her way. Finally, as she later recalled, the family members noticed her abnormalities and she was exorcised many times, but the rituals proved to no avail. Even scolding and punishments failed to change her outrageous unacceptable behavior. She fail to change as a child because, it seems, after the servant boy drown, plus the attention she was receiving, she felt she was powerful and invulnerable, and increasingly believed that mighty forces would carry out her wishes. A belief that seemed to permeate her life.

Her only happy childhood memories seem to be between six and twelve in her father's army camps. She was petted and spoiled as the enfant du regiment. She tyrannized over her father's orderlies whom she preferred to her female nurses and governesses. While being pampered she managed to pickup a smattering of knowledge about shamans and magic which she put to good use later in life.

After the death of their mother, at age 28, Helena with her sister and brother lived with their maternal grandparents. The grandmother, Helena Palovna de Fadeev, was a princess of the Dolgorkurov family, and a famous botanist. So from her mother and grandmother HPB inherited her characteristics of stubbornness, a fiery temper, and a disregard for social norms, all of which she amplified.

Helena's first love affair, at age 16, had been with Prince Alexander Galistin, cousin to the Viceroy of the Caucasus. At the time her grandfather served as his Imperial Councilor. Her interest in the Prince was because of his interest in occultism and magic. She later claimed the affair ended on the Prince's death, but he jilted her.

When 17 she married General Nicephore Blavatsky. There are several stories for this marriage, but it seems to be that a governess had scolded Helena for her temper tantrums, saying she could not even get an old man to marry her. To prove the governess wrong, and to divert attention from her unhappy affair with Prince Galistin she married Blavatsky, who she called old and about seventy or eighty. Actually he was around forty when they married and outlived her. After three unhappy months of a honeymoon, HPB managed to escape from the General's bodyguards and return to her grandfather who was not glad to see her. Her quickly shipped her off to her father, now retired and living near St. Peterburg, in charge of a maid and three men servants, all of whom she escaped. Her father traveled two thousand mile for nothing to meet her in Odessa. Helena was aboard an English bark, some say eloping with the skipper, sailing for Constantinople.

The years between 1848-1858 are known as Helena's vagabond years. The actual events are rather sketchy. The important thing to HPB, at least, was the two years she was in Tibet studying with the Lama. In 1856, according to her version, while in India she met a Lutheran minister who was with two mystics. None had passports or proper identification. The mystics did not enter Tibet, but the minister, although not permitted in the country, did travel a good way with the party to a mud hut. Helena wore a mysterious disguise supplied by a Tartar shaman. At a hut they met the Chief Lama who would not allow them admittance until Helena showed him a carnelian talisman given to her as a child by a high priest of a Calmuck tribe.

Within the hut, which was a great hall, they witnessed a reincarnation ceremony. A four-month-old baby laid on a carpet in the center of the hall. "Under the influence of the venerable lama, the baby rose to its feet and walked up and down the strip of carpet, repeating, `I am Buddha, I am the old Lama, I am his spirit in a new body.'" The three men accompanying Helena were terrified. The minister said his blood ran cold because the infant's eyes "seemed to search his very soul."

Some believe that HPB fabricated the reincarnation story because similar descriptions could be found in Abbe Huc's Recollection's of Travel in Tartary, Tibet and China Further they reasoned, her reason for the story was for psychological importance, showing she had traveled in Tibet where other men could not, and her talisman had admitted them to see the ritual; however, it must be remembered these were her critics.

When returning to Russia Helena agreed to return to Nicephore Blavatsky on the condition that she would be required to see him as little as possible, which she did. Also, at this time her grandfather Andrey Fadeyev was 71 and retiring from the Viceroy's Board of Caucasus. He usually retired early and Helena's two cousins, both unmarried, came to the Fadeyev home in Taiflis to entertain while seances were held. At the time the many of the Russian intellectuals were beginning to be fascinated with the paranormal. Helena made a big impression. Her cousin Sergei Witte wrote, "My cousin did not confine the demonstrations of her power to table rapping, evocation of spirits, and similar mediumistic hocus-pocus. On one occasion she caused a closed piano in an adjacent room to emit sounds as if invisible hands were playing upon it. This was done in my presence, at the insistence of one of the guests."

It seemed that the lady's activities included more than hold seances. A young baron from Estonia, Nicholas Meyendorff who was an ardent Spiritualist, found HPB delightful. Meyendorff was a closed friend of D. D. Home, in fact, he considered Home as a brother, so he confided his affair with HPB to Home. He insisted she divorced Blavatsky and marry him, or so the lady later claimed.

It seems Meyendorff later said Helena was unfaithful. From latter correspondence, in 1886, to her biographer it seems that Meyendorff was correct. About this time unexpectedly Agardi Metrovich appeared sometime in the early 1860's. He was an opera singer accompanied by a female singer who it seems was his wife. Metrovich had know Helena and her family previously. It seems he now wanted her back. He was almost sixty in 1861, and had about begged an engagement from the Italian Opera of Tiflis was one of the worst in Europe. He was on a decline in his career.

It is somewhat of a puzzle how Helena managed living with her husband, lover Meyendoroff, and Metrovich at the same time while holding seances in her grandfather's home. But, the fact is that she became pregnant and a child was born. The only existence of the child's birth date is on a passport dated August 23 "(Old Style)" 1862. It designated him as an infant, leaving speculation he was born in 1862, or late 1861. His name was Yuri, and he was deformed. He was born in the settlement of Ozurgety which had a military surgeon. Helena settled there buying a house to escape the scandal her pregnancy had caused in Tiflis. All men she knew denied fathering the child, but Blavatsky continued her monthly allowance. Helena referred to him as "the poor crippled child," while Meyendorff's relatives said he had a hunchback. Whether the handicap resulted from a birth defect or an accident cause by the military physician unaccustomed delivering babies is not known.

After the birth Helena suffered, or arranged, a nervous breakdown. The significance of which is that she describes a dual personality:

"When awake and myself, I remembered well who I was in my second capacity, and what I had been and was doing. When someone else, i.e., the personage I became, I know I had no idea of who was H. P. Blavatsky! I was in another far-off country, a total different individuality from myself, and had no connection at all with my actual life."

Yuri was about five years when Helena took him Bologna trying to help him. It is known that Metrovitch accompany them. But, the journey proved fruitless and the child died. They buried him in a small town in Southern Russia under Metrovitch's name; the latter saying that "he did not care."

Even though Helena had reason to detest Russia, she could not bury her son on foreign soil. This among other things illustrated that she dearly loved the child. It had been difficult for her to keep the child, and easier for her to have abandoned him as an orphan, but this she did not do. She did everything she could for him. Although later she denied he was her child. When taking him to visit her father, she wrote that her father suspected her of wrongful sexual conduct and she produced evidence from two doctors that she was unable to bare children. Perhaps she did this more for Yuri's sake than her own, because, it is thought, she could not bear for anyone to think ill of her son. She also claimed Yuri was an illegitimate child of Meyendorff and a friend of hers. The stories she told got so tangled that her biographer. Alfred Sinnett, omitted Yuri altogether.

However, the child seems an important factor in her life; otherwise, why would she have cared for him approximately five years? Her career in the paranormal was of great concern to her. Factors concerning the child outweighed this. Yuri, ironically, resembled the little hunchback invisible which she had played with in her own childhood. She, herself, described Yuri as "the only being who made life worth living, a being whom I loved according to the phraseology of Hamlet as `forty thousand fathers and brothers will never love their children and sisters.'" Later she wrote to Metrovitch, "'I loved one man deeply but still more I love occult science,' but the one she loved `more than anything else in all the world,' or anything, was Yuri."

It was later after Yuri's death that Helena confided in writing to her cousin Nadyezha Fadeyev of her rejection of Christianity, "the Russian Orthodox god had died for her on the day of Yuri's death." Although, she had never been at peace with Christianity, "there were moments when I believed deeply that sins can be remitted by the Church, and that the blood of Christ has redeemed me, together with the whole race of Adam."

Yet it should be noted toward the end of Helena's life, as with so many others, the encroachment of fragments of an earlier religious experience are seen. Increasingly in her writings she used words like the Holy Cause, with their ecclesiastical flavor, phrases reminiscent of the childhood religion which she had rebelled against all of her life. She was humbling her pride to join the host of other rebel spirits who creep back to the sanctity of the Holy Church. She even admitted when in Paris she had in secrecy slipped off to the Russian Cathedral. In secrecy was correct, because even though in her heart toward the end her life her confidence in her Mahatmas and the occult may have decrease or fallen away, in public her concern was to insure the realty of her Masters Morya and Koot Hoomi and all the hierarchy for her followers. She apologized for the mistakes and misrepresentations in her works but not for the Masters who had dictated her books. The faults of the books she laid on others.

After 1869 both the Fadeyev and Witte families had dwindled. Adey Fadeyev had died at 81. The families pooled their assets and moved to Odessa where Helena and Metrovitch joined them. It was tough going for everyone, but Helena, in her flighty manner, tried starting several small businesses, but in the perilous times they all failed. Metrovitch still trying to make a comeback got an engagement with the Italian opera of Cairo, so he and Helena sailed for Egypt.

It was during their voyage that Metrovitch lost his life in an explosion of gunpowder and fireworks which the ship was carrying. Helena was one of seventeen passengers out of 400 which survived. She latter said Metrovitch died trying to save her life, although there are other versions of his death which are not connected with the explosion at all. Anyway Helena thought that Metrovitch would want her to go on. She went to Alexandria with help of the Greek government funds. It is thought she buried Metrovitch's remains there, and then proceeded to Cairo when she became a medium by teaming up with another woman. The relationship in Cairo lasted for some time, then both went back to Odessa. However, Russia did not provide the stimulation which Helena longed for, and she tired of quarreling with her aunts whom she said did not understand her. She saw other people and then went to Paris. It was there she heard of the enthusiasm for Spiritualism that was spreading in the United States. She almost immediately sailed, saying that it was "my mysterious Hindu" that ordered her "to embark for North America, which I did without protesting."

She did not travel first class though. On the dock at Le Havre she by chance met a German peasant and her children who had been sold bogus tickets. Helena gave the woman and children her deluxe passage and traveled herself in steerage because that was all she could then afford. She, like millions of other poor emigrants, and rebellious aristocrats traveled to America, the land of opportunity and hope. It was her second chance.

As with thousands of other immigrants Helena's second chance did not come easy, but she was determined to obtain it. It was July, 1873 when she reached New York. As did other single women, she first lodged in a home for woman that was a tenement house that had be made into a cooperative by the 65 occupants. The landlord introduced Helena to the owners of a shirt-and-collar factory where she tried selling elaborate designs to the owners. The designs were good but she was bad at selling, so it was Odessa all over again.

HPB was penniless but said that she had wrote home to her relatives for money and expected to receive it from the Russian Council at anytime. This is how she survived in the home. She managed to divide the home into two groups, those not liking her and those that did. She entertained the latter group with stories of her life and by holding seances on Sunday nights. This seemed to work until a newspaper took a dislike to her and accused her of using hashish and opium.

Soon after this her father died and she received $500 of her modest inheritance which went fast. She moved into a smart hotel and began to live Bohemian again in a cooperate flat with three journalists, two men and another woman. Then a new phenomenon appeared. Ordinary photographs left in a wooden box overnight were found in the morning to be tinted with water colors by spirits. Although impressive, the others occupants became skeptical of HPB's powers. Then one night they watched the Madame leave her room in night clothes, carrying paint and brushes to assist the spirits.

Following this HPB worked whenever she could, one job was in a sweatshop making artificial flowers, and accepting charity from whomever gave it. This continued until June, 1874 when she met Clementine Jerebko and her husband who has just arrived from Caucasus. She had known them both in Russia. The Jerebkos had just bought farmland on Long Island and HPB agreed to join in the adventure by buying in at $1,000. By the end of the first month all parties knew it was a disastrous decision. Clementine agreed to return Helena's money after the farm been sold by auction, but three days later she and her husband disappeared. Helena tried pursuing them by hiring a creditable law firm which took the case to court.

The next important event in her life occurred ten days after Henry Steele Olcott's first article on the Eddy seances appeared in New York, on October 14, 1874, when she introduced herself to Olcott at the remote Chittenden, Vermont farm. Immediately she claimed to be a spiritualist who had spend fifteen years in the cult, but it soon became apparent that she had come to see Olcott.

During the next ten days Helena exhibited her techniques. Her seances accompanied those of the Eddy Brothers. Although Olcott was not a Spiritualist, he had a keen interest in the phenomena. Each night the seance began at ten minutes to seven. The procession of apparitions began drifting in and out of the Eddy cabinet on the schedule of every one to five minutes. The appearances of Honto and the Indians were slightly dim compared to Madame Blavatsky's peopled apparitions. "Hassan Aga," the wealthy merchant wearing a black Astarkhan cap and tasseled hood who said three times he had a secret to revel, but never did; "Safer Ali Bak," the man that guarded Helena for Nicephore Blavatsky in Erivan, now appearing as a Kurd warrior carrying a feathered spear; a Circassian noukar who bowed, smiled and said, "Tchock yachtchi (all right); a giant muscular black man in white-and-gold-horned headdress, a conjurer who she had met in Africa. Also, there were less exotic phantoms such as an old woman in a babushka, whom Helena said was Vera's nurse; and the portly man in a black evening suit and frilled white shirt, around whose neck hung a Greek cross of St. Anne suspended by a red moiré ribbon with two black stripes.

"Are you my father?" she asked, confessing later that she was trembling.

The apparition approached her and stopped, "Djadja," he answered reproachfully.

HPB knew that Olcott was enthused with her performance, although his articles about her would not be published for several weeks, she decided much could be achieved in the meantime. She with another medium rushed back to New York. When Olcott mentioned putting his collection of articles that appeared in the Graphic into a book she volunteered to translate them into Russian for the Psychisen Studien or some other Russian journal. Olcott was thrilled with the idea.

She did like Olcott, but still considered him childish and gullible. She knew, even though she had warned him that William Eddy's spooks were not necessarily proof of spirit entities, that Olcott was "in love with the spirits," as she put it. Nevertheless, they continued working together. HPB had feelings for Olcott, but they were not mutually shared at first. Olcott considered her androgynous. He just did not see her as an attractive sexual person, even though she was in her earthly, sensual manner.

It was at this time that she engaged in a confrontation with a New York neuropathologist, Dr. George Beard, who claimed in the Daily Graphic that the Eddy brothers were frauds and that Colonel Olcott had been blinded by a handful of bad magicians' tricks. HPB had two reasons to be upset by the article. First, her first real success in Spiritualism might be thwarted; and secondly, the article questioned Olcott's integrity as a serious investigator. If this went unchallenged it would dash any hopes of selling any translations of his articles. This episode became a fight between Beard and Helena, but took an unexpected turn when she was recognized by both the Spiritual Scientist and Daily Graphic. The editor of the former said he would publish all she could write. In an interview with the Graphic she gained so much publicity that Helena Blavatsky was known throughout the New York area.

But, as usual, her troubles were not over. She had tried to sell the Russian translation of Olcott's articles through Andrew Jackson Davis who admired her as a medium, a friend of Alexander Aksakov who could get the articles in the Psychisen Studien. In his reply to Davis, Aksakov said that he had heard of Madame Blavatsky, and she was a powerful medium, but her communications show moral flows. Toward Davis Helena appeared casual, and Davis thought his friend didn't know her as well as he did. However, Helena suspected Aksakov had heard rumors and hastily sent a letter to him pleading with him not to exposed everything to Davis. It is later noted that Alsakov did receive some of the translations, but he never printed them, nor did any other publication.

Fearing that Aksakov revelations would come down upon her at any time Helena was in a desperate period. She still conducted seances, hoping for the best. She still needed financial support. The man, Henry Olcott, she wanted was unavailable to her. Olcott was supporting an estranged wife and two children, also his law practice had been neglected during his Spiritualism investigations. Michael Betanelly was available and wanted to marry her to look after her, he said he would expect no martial privileges of her. Betanelly was friend to both Helena and Olcott. It was Betanelly who had written a letter to Olcott, on Helena's behalf, verifying the Georgian that materialized during a seance at Chittenden. The letter was to served to disprove Dr. Beard's accusations aimed at Olcott and also give Olcott more creditability. The truth was that Betanelly knew nothing about Spiritualism when writing the letter.

Helena and Betanelly were married on April 3, 1875. They had not told Olcott, when he heard of the marriage he called it "a freak of madness." He later said he had ridiculed her for marrying a man so much younger than herself and unequal to her mental capacity. However, Helena already had her defense planned: she said, " their fates were linked by karma, and the marriage was her punishment for `awful pride and combativeness.'" She added that Betanelly had threaten suicide if she did not marry him. Helena assured Olcott the marriage would not be consummated; although her reason was not clear, it would seem she did so because of her interest in Olcott. Olcott believed her. It may have been a non-sexual marriage, but it is doubtful her entire relationship with Betanelly was non-physical.

Helena's main concern seemed to always lie in Olcott. To her he was always essential to the Spiritualist movement. Later many would say she broke up his marriage, even though the Spiritualists eventually denied it, it is a fact they met shortly before his divorce. But it seemed they just collaborated, with HPB being dominate, at first, intimacy would come later. HPB dictated Olcott's writings and where to send them. Before the establishment of the Theosophical Society there was the founding of the Miracle Club. This was a club where members were admitted to seances conducted by the club medium David Dana, brother of Charles Dana editor of the New York Sun, and suggested by HPB. Members were forbidden to disclose their experiences or the address of the meeting place. The club only lasted a few weeks because David wanted to be paid, which HPB did not agree to.

The failure of the Miracle Club, however, sparked the founding of the Theosophical Society. The membership itself, with the enthusiasm of HPB, did not disperse. In striving to find a common purpose Olcott scribbled a hasty note asking, "Would it not be a good thing to form a society for this kind of study?" The phrase this kind of study referred to subjects such as the Egyptian mysteries and the kabbalah which had been discussed in a lecture previously given to an informal group by J. H. Felt, an architect and engineer. He had said, "the dog-and hawk-headed figures of Egyptian hieroglyphics were accurate pictures of elementals, the spirits who convey messages at seances."

The infant society was eagerly formed in September1875. It was co-founded by Olcott along with William Q. Judge. Its name was furnished by Charles Sotheran who was of independent means, a high Mason, a Rosicrucian, and a student of the kabbalah. Sotheran thought the name of the Miracle Club was too cheap; he considered Egyptological Society, too limited; looking through a dictionary, he found the word theosophy, a word that was unanimously agreed on at the next meeting because it seemed to express esoteric truth as well as covering the aspects of occult scientific research, both of which were goals of the Society. Because of Olcott's love for red tape and Helena's ritualism the Society included all of the pomp originally planned for the Miracle Club. There was the policy of secrecy, each member wrote F.T.S (Fellow, Theosophical Society) after their name, and recognized each other by secret signs, most of which were borrowed from Egyptian occultism and the Grand Lodge of Cairo.

After its establishment the Theosophical Society expounded the esoteric tradition of Buddhism aiming to form an universal brotherhood of man, studying and making known the ancient religions, philosophies and sciences, and investigating the laws of nature and divine powers latent in man. The direction of the society was claimed to be directed by the secret Mahatmas or Masters of Wisdom.

After reading the evidence of the letters supposedly written from these Mahatmas many concluded that they were written by friends of HPB, or by HPB herself. The letters conveyed her ideas. These conclusions were drawn after earnest men and women lavished an aggregate of several lifetimes of study and research on the Mahatmas letters. Several books and monographs, pro and con, were written. Who Wrote the Mahatmas Letters, a book by the Hare brothers, one a disillusion Theosophist, was a well researched work.

Although there is not any certain evidence of these Mahatmas or Masters of Wisdom, Helena's first book Isis Unveiled, 1877, outlined the basic precepts and the secret knowledge which they protected. In the book's preface HPB inserted `a plea for the recognition of the Hermetic philosophy, the ancient universal wisdom." The success of the book was greater than that of the society, which by 1878 almost collapsed.

In July 1878 Helena P. Blavatsky became the first Russian woman to acquire United States citizenship. Some say she did so not to have the English in India think she was a Russian spy. She and Olcott went to India in December of that year in order to revive the society's study of Hindu and Buddha religions.

It was in India that HPB and the society gained much support. Newly acquired supporters included Sinnett, the statesman Allen O. Hume, and various high-caste Indians and English officials. At this time HPB aided Sinnett and Hume in corresponding with the Masters Koot Hoomi and Morya. From this the first suspicions of the Masters occurred, when their handwriting closely resembled that of HPB. However, nothing was every proven conclusively.

In 1882 the headquarters of the society was moved to an estate in Adyar, near Madras. There HPB had a shrine room constructed for the Mahatmas where they could directly manifest their communications. A former colleague of HPB, Emma Cutting Coulomb and her husband managed the household. They were later discharged for dishonest practices.

In 1884 HPB and Olcott toured Europe while in the United State the Coulomb's published letters which they claimed to be written by HPB containing instructions for the Masters' manifestations and for the operation of the shrine through secret black panels. Apparently, the panels were constructed by Coulomb during HPB's absent to destroy her reputation. During December 1884, Richard Hodgson of the Psychical Research Society (PRS) in London went to Adyar to investigate the activity there. In the following spring he released a scathing report alleging fraud and trickery by HPB and her associates. To HPB and the Theosophical Society the report was controversial for over one hundred years. It put a tarnish upon the name of HPB and the Society. In 1986 the PRS published an article in its Journal calling the report prejudiced, saying that Hodgson had ignored all evidence favorable to HPB, and, that an apology was due.

Because of the controversy, Olcott sent HPB to Europe in 1885, where she toured different countries finally settling in Germany due to deteriorating health. By then the French-born Swedish Countess Constance Wachrmeister had moved in with HPB and helped her with her work, especially her second book, The Secret Doctrine (1888), which is said to be her greatest work.

The Secret Doctrine outlined a scheme of evolution relating to the universe (cosmogenesis) and humankind (anthropogenesis), and is based on three premises: (1) Ultimate Reality, as an omnipresent, transcendent principle beyond the reach of thought; (2) the universality law of cycles throughout nature; and (3) the identity of all souls with the Universal Oversoul and their journey through many degrees of intelligence by means if reincarnation, in accordance with "Cyclic and Karmic law."

The Secret Doctrine is claimed to have been largely based on the archaic manuscript of The Book of Dyzan, which HPB interpreted. She claimed the Mahatmas communicated parts of The Secret Doctrine to her, claiming they impressed thoughts in her mind which she put to paper. Critics say she copied her thoughts from various existing works.

During 1889 HPB finished two more books: The Key to Theosophy an introduction to theosophical thought and philosophy; and, The Voice of the Silence, a mystical and poetic work on the path of enlightenment.

The work of the Theosophical Society was continued by activist Annie Wood Besant, a reviewer of The Secret Doctrine and a convert to Theosophy. Besant's home in London became the headquarters of the Society. She actively supported progressive causes, bringing another generation of liberal intellectuals into the society, and became president following Olcott's death in 1907.

In all respects it is not difficult to believe that HPB possessed genuine occult inspiration and powers for she exerted enormous influence over some of the most talented individuals of her time. Touched by her were persons like Horace Greeley, the Honorable John L. O'Sullivan, ex-Ambassador to Portugal; P. B. Randolph, leading American Rosicrucian; Prince Wittgenstein.

Also among those influenced by her are W. B. Yeats, the Irish poet, and "AE" (George W. Russell). She was influential in the development of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn by promoting the translations of Hindu scriptures and philosophical works.HPB died in her home on May 8, 1891. She became unable to walk and suffered from various diseases. She was cremated with a third of her ashes remaining in Europe, and a third going to America and India each. Theosophists commemorate her death on May 8, called White Lotus Day.

It would not be a mere understatement to say Madame's Blavatsky's life was different, because it was very different. There seems to be no single reason for this difference; one cannot say it was just her childhood, her adolescence, her adult life; the lost of her son, or the child she dearly loved; or her love of occult science. One is forced to say that is was several or all of these factors which made her different and who she was. Over a hundred years following her death people are still fascinated by the name of Madame Helena Blavatsky.

One presumes this fascination is generated by the unique pursuit of Madame Blavatsky's life itself. One never could say she allowed life to pass her by; if anything, she propelled life. Divine revelations appealed to her for she was mystical by nature. Yori resembled her invisible playmate in early childhood. She did not share Christian visions because of her violent rebellion against the church. A heaven containing thousands of angelic creatures was not for her. She was too earthy. Her life was with people. Her saints were the Mahatmas or Masters of Wisdom, modeled on Buddhist and Christian monks, who resided in the inaccessible portion of the earth. They were the "old souls" who had completed their rounds of incarnations on earth, but frequently returned to help members of humankind who deserved it: the Theosophists.

Even though many have been and are skeptical of HPB, and it must be said they have cause to be, it cannot be believed she deliberately intended to hurt people. Although some of her ways were suspicious, it is doubtful that she intentionally exploited people with her glimpses of the truth. This seems contradictory to the nature of a woman who gave her deluxe accommodations to a peasant family and came to America in steerage. She seemed to possess a strange and uncanny power, even in youth, to hurl defiance in the face of polite society, and then force it to take her seriously. Perhaps this is the charm and complexity of Madame Blavatsky which even today compels some individuals to try and follow her. A.G.H.