Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

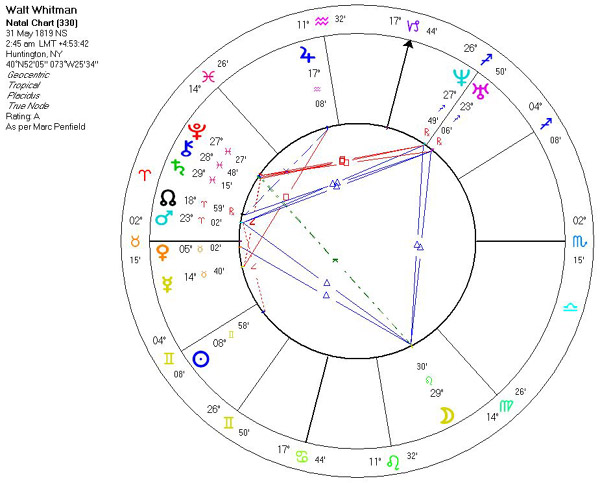

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

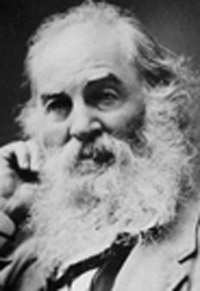

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

A morning-glory at my window satisfies me more than the metaphysics of books.

After you have exhausted what there is in business, politics, conviviality, and so on - have found that none of these finally satisfy, or permanently wear - what remains? Nature remains.

(Venus in Taurus conjunct Ascendant.)Be curious, not judgmental.

(Gemini Sun.)Behold I do not give lectures or a little charity, When I give I give myself.

(Leo Moon.)Camerado, I give you my hand, I give you my love more precious than money, I give you myself before preaching or law; Will you give me yourself?

Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes.

Every moment of light and dark is a miracle.

Freedom - to walk free and own no superior.

Give me odorous at sunrise a garden of beautiful flowers where I can walk undisturbed.

Have you heard that it was good to gain the day? I also say it is good to fall, battles are lost in the same spirit in which they are won.

Here or henceforward it is all the same to me, I accept Time absolutely.

How beggarly appear arguments before a defiant deed!

(Mars in Aries conjunct North Node.)I accept reality and dare not question it.

I am as bad as the worst, but, thank God, I am as good as the best.

I am for those who believe in loose delights, I share the midnight orgies of young men, I dance with the dancers and drink with the drinkers.

I believe a leaf of grass is no less than the journey-work of the stars.

I cannot be awake for nothing looks to me as it did before, Or else I am awake for the first time, and all before has been a mean sleep.

I celebrate myself, and sing myself.

I dote on myself, there is that lot of me and all so luscious.

I find no sweeter fat than sticks to my own bones.

I have learned that to be with those I like is enough.

(Gemini Sun.)I heard what was said of the universe, heard it and heard it of several thousand years; it is middling well as far as it goes - but is that all?

I no doubt deserved my enemies, but I don't believe I deserved my friends.

I say that democracy can never prove itself beyond cavil, until it founds and luxuriantly grows its own forms of art, poems, schools, theology, displacing all that exists, or that has been produced anywhere in the past, under opposite influences.

I say to mankind, Be not curious about God. For I, who am curious about each, am not curious about God - I hear and behold God in every object, yet understand God not in the least.

I see great things in baseball. It's our game - the American game.

If any thing is sacred, the human body is sacred.

Nothing can happen more beautiful than death.

Nothing endures but personal qualities.

Now I see the secret of making the best person: it is to grow in the open air and to eat and sleep with the earth.

(Taurus Ascendant.)Speech is the twin of my vision, it is unequal to measure itself, it provokes me forever, it says sarcastically, Walt you contain enough, why don't you let it out then?

(Gemini Sun.)The art of art, the glory of expression and the sunshine of the light of letters, is simplicity.

There is no object so soft but it makes a hub for the wheeled universe.

To die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.

To have great poets, there must be great audiences too.

Whitman was born in a white farmhouse near present-day South Huntington, New York, on Long Island, New York, in 1819, the second of nine children. In 1823, the Whitman family moved to Brooklyn. Whitman attended school for only six years before starting work as a printer's apprentice. He was almost entirely self-educated, reading especially the works of Homer, Dante and Shakespeare.

After a two year apprenticeship, Whitman moved to New York City and began work in various print shops. In 1835, he returned to Long Island as a country school teacher. Whitman also founded and edited a newspaper, the Long-Islander, in his hometown of Huntington in 1838 and 1839. Whitman continued teaching in Long Island until 1841, when he moved back to New York City to work as a printer and journalist. He also did some freelance writing for popular magazines and made political speeches. In 1840, he worked for Martin Van Buren's presidential campaign.

Whitman's political speeches attracted the attention of the Tammany Society, which made him the editor of several newspapers, none of which enjoyed a long circulation. For two years he edited the influential Brooklyn Eagle, but a split in the Democratic party removed Whitman from this job for his support of the Free-Soil party. He failed in his attempt to found a Free Soil newspaper and began drifting between various other jobs. Between 1841 and 1859, edited one newspaper in New Orleans (the Crescent), two in New York, and four newspapers in Long Island. While in New Orleans, Whitman witnessed the slave auctions that were a regular feature of the city at that time. At this point, Whitman began writing poetry, which took precedence over other activities.

The 1840s saw the first fruits of Whitman's long labor of words, with a number of short stories published, beginning in 1841, and one year later the temperance novel, "Franklin Evans," published in New York. However, one often-reprinted short story, "The Child's Champion," dating from 1842, is now recognized to be the most important of these early works. It established the theological foundation for Whitman's lifelong theme of the profoundly redemptive power of manly love.

The first edition of Leaves of Grass was self-published at Whitman's expense in 1855, the same year Whitman's father passed away. At this point, the collection consisted of 12 long, untitled poems. Both public and critical response was muted. A year later, the second edition, including a letter of congratulations from Ralph Waldo Emerson, was published. This edition contained an additional twenty poems. Emerson had been calling for a new American poetry; in Leaves of Grass, he found it.

.During the American Civil War, Whitman cared for wounded soldiers in and around Washington, D.C. He often saw Abraham Lincoln in his travels around the city, and came to greatly admire the President. Whitman's poems "O Captain! My Captain!" (popularized in the 1989 movie Dead Poets Society) and "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed" were influenced by his profound grief after Lincoln's assassination in 1865.

After the Civil War, found a job as a clerk in the U.S. Department of the Interior. However, when James Harlan, Secretary of the Interior, discovered that Whitman was the author of the "offensive" Leaves of Grass, he fired Whitman immediately.

By the 1881 seventh edition, the collection of poetry was quite large. By this time Whitman was enjoying wider recognition and the edition sold a large number of copies, allowing Whitman to purchase a home in Camden, New Jersey.

Whitman died on March 26, 1892, and was buried in Camden's Harleigh Cemetery, in a simple tomb of his own design.

For many, and Emily Dickinson stand as the two giants of 19th-century American poetry. Whitman's poetry seems more quintessentially American; the poet exposed common America and spoke with a distinctly American voice, stemming from a distinct American consciousness. The power of Whitman's poetry seems to come from the spontaneous sharing of high emotion he presented. American poets in the 20th century (and now, the 21st) must come to terms with Whitman's voice, insofar as it essentially defined democratic America in poetic language. Whitman utilized creative repetition to produce a hypnotic quality that creates the force in his poetry, inspiring as it informs. Thus, his poetry is best read aloud to experience the full message. His poetic quality can be traced indirectly through religious or quasi-religious speech and writings such as the Harlem Renaissance poet James Weldon Johnson. This is not to limit the man's influence; the beat poet Allen Ginsberg's reconciliation with Whitman is revealed in the former's poem, A Supermarket in California. The work of former United States Poet Laureate, Robert Pinsky, bears Whitman's unmistakable imprint as well.

Furthermore, Whitman is one of the few American writers whose influence reaches far beyond his native homeland—he is especially influential in Latin America and the Hispanic World, where some of his more famous successors include the Chilean Nobel Laureate Pablo Neruda as well as Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa.

Another topic intertwined with Whitman's life and poetry is that of homosexuality and homoeroticism, ranging from his admiration for 19th-century ideals of male friendship to outright masturbatory descriptions of the male body ("Song Of Myself"). This is in sharp contradiction to the outrage Whitman displayed when confronted about these messages in public, praising chastity and denouncing onanism. However, the modern scholarly opinion tends to be that these poems reflected Whitman's true feelings towards his sex and that he merely tried to cover up his feelings in a homophobic culture. For example, in "Once I Pass'd Through A Populous City" he changed the sex of the beloved from male to female prior to publication. He even went so far as to invent six illegitimate children to correct his public image.

During the American Civil War, the intense comradeship (which often turned sexual) at the front lines in Virginia, which were visited by Whitman in his capacity as a nurse, fueled his ideas about the convergence of homosexuality and democracy. In "Democratic Vistas", he begins to discriminate between amative (i.e., heterosexual) and adhesive (i.e., homosexual) love, taking cues from the pseudoscience of phrenology. Adhesive love is portrayed as a possible backbone of a better form of democracy, as a "counter-balance and offset of our materialistic and vulgar American democracy and for the spiritualization thereof".

In the 1970s, the gay liberation movement made Whitman one of their poster children, citing the homosexual content and comparing him to Jean Genet for his love of young working-class men ("We Two Boys Together Clinging"). In particular the "Calamus" poems, written after a failed and very likely homosexual relationship, contain passages that were interpreted to represent the coming out of a gay man. The name of the poems alone would have sufficed to convey homosexual connotations to the ones in the know at the time, since the calamus plant is associated with Kalamos, a god in antique mythology who was transformed with grief by the death of his lover, the male youth Karpos.

1819 Was born on May 31.

1841 Moves to New York City.

1855 Father, Walter, dies. First edition of Leaves of Grass.

1862 Visits his brother, George, who was wounded in the Battle of Fredericksburg.

1865 Lincoln assassinated. Drum-Taps, Whitman's wartime poetry (later incorporated into Leaves of Grass), published.

1871 Stroke. Mother, Louisa, dies.

1882 Meets Oscar Wilde. Publishes Specimen Days & Collect.

1888 Second stroke. Serious illness. Publishes November Boughs.

1891 Final edition of Leaves of Grass.

1892 dies, on March 26.

arguably America's most influential and innovative poet, was born into a working class family in West Hills, New York, a village near Hempstead, Long Island, on May 31, 1819, just thirty years after George Washington was inaugurated as the first president of the newly formed United States. was named after his father, a carpenter and farmer who was 34 years old when Whitman was born. Walter Whitman, Sr., had been born just after the end of the American Revolution; always a liberal thinker, he knew and admired Thomas Paine. Trained as a carpenter but struggling to find work, he had taken up farming by the time Walt was born, but when Walt was just about to turn four, Walter Sr. moved the family to the growing city of Brooklyn, across from New York City, or "Mannahatta" as Whitman would come to call it in his celebratory writings about the city that was just emerging as the nation's major urban center. One of Walt's favorite stories about his childhood concerned the time General Lafayette visited Brooklyn and, selecting the six-year-old Walt from the crowd, lifted him up and carried him. Whitman later came to view this event as a kind of laying on of hands, the French hero of the American Revolution anointing the future poet of democracy in the energetic city of immigrants, where the new nation was being invented day by day.

is thus of the first generation of Americans who were born in the newly formed United States and grew up assuming the stable existence of the new country. Pride in the emergent nation was rampant, and Walter Sr.—after giving his first son Jesse (1818-1870) his own father's name, his second son his own name, his daughter Mary (1822-1899) the name of Walt's maternal great grandmothers, and his daughter Hannah (1823-1908) the name of his own mother—turned to the heroes of the Revolution and the War of 1812 for the names of his other three sons: Andrew Jackson Whitman (1827-1863), George Washington Whitman (1829-1901), and Thomas Jefferson Whitman (1833-1890). Only the youngest son, Edward (1835-1902), who was mentally and physically handicapped, carried a name that tied him to neither the family's nor the country's history.

Walter Whitman Sr. was of English stock, and his marriage in 1816 to Louisa Van Velsor, of Dutch and Welsh stock, led to what Walt always considered a fertile tension in the Whitman children between a more smoldering, brooding Puritanical temperament and a sunnier, more outgoing Dutch disposition. Whitman's father was a stern and sometimes hot-tempered man, maybe an alcoholic, whom Whitman respected but for whom he never felt a great deal of affection. His mother, on the other hand, served throughout his life as his emotional touchstone. There was a special affectional bond between Whitman and his mother, and the long correspondence between them records a kind of partnership in attempting to deal with the family crises that mounted over the years, as Jesse became mentally unstable and violent and eventually had to be institutionalized, as Hannah entered a disastrous marriage with an abusive husband, as Andrew became an alcoholic and married a prostitute before dying of ill health in his 30s, and as Edward required increasingly dedicated care.

A Brooklyn Childhood and Long Island Interludes

During Walt's childhood, the Whitman family moved around Brooklyn a great deal as Walter Sr. tried, mostly unsuccessfully, to cash in on the city's quick growth by speculating in real estate—buying an empty lot, building a house, moving his family in, then trying to sell it at a profit to start the whole process over again. Walt loved living close to the East River, where as a child he rode the ferries back and forth to New York City, imbibing an experience that would remain significant for him his whole life: he loved ferries and the people who worked on them, and his 1856 poem eventually entitled "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry" explored the full resonance of the experience. The act of crossing became, for Whitman, one of the most evocative events in his life—at once practical, enjoyable, and mystical. The daily commute suggested the passage from life to death to life again and suggested too the passage from poet to reader to poet via the vehicle of the poem. By crossing Brooklyn ferry, Whitman first discovered the magical commutations that he would eventually accomplish in his poetry.While in Brooklyn, Whitman attended the newly founded Brooklyn public schools for six years, sharing his classes with students of a variety of ages and backgrounds, though most were poor, since children from wealthy families attended private schools. In Whitman's school, all the students were in the same room, except African Americans, who had to attend a separate class on the top floor. Whitman had little to say about his rudimentary formal schooling, except that he hated corporal punishment, a common practice in schools and one that he would attack in later years in both his journalism and his fiction. But most of Whitman's meaningful education came outside of school, when he visited museums, went to libraries, and attended lectures. He always recalled the first great lecture he heard, when he was ten years old, given by the radical Quaker leader Elias Hicks, an acquaintance of Whitman's father and a close friend of Whitman's grandfather Jesse. While Whitman's parents were not members of any religious denomination, Quaker thought always played a major role in Whitman's life, in part because of the early influence of Hicks, and in part because his mother Louisa's family had a Quaker background, especially Whitman's grandmother Amy Williams Van Velsor, whose death—the same year Whitman first heard Hicks—hit young Walt hard, since he had spent many happy days at the farm of his grandmother and colorful grandfather, Major Cornelius Van Velsor.

Visiting his grandparents on Long Island was one of Whitman's favorite boyhood activities, and during those visits he developed his lifelong love of the Long Island shore, sensing the mystery of that territory where water meets land, fluid melds with solid. One of Whitman's greatest poems, "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking," is on one level a reminiscence of his boyhood on the Long Island shore and of how his desire to be a poet arose in that landscape. The idyllic Long Island countryside formed a sharp contrast to the crowded energy of the quickly growing Brooklyn-New York City urban center. Whitman's experiences as a young man alternated between the city and the Long Island countryside, and he was attracted to both ways of life. This dual allegiance can be traced in his poetry, which is often marked by shifts between rural and urban settings.

Self-Education and First Career

By the age of eleven, Whitman was done with his formal education (by this time he had far more schooling than either of his parents had received), and he began his life as a laborer, working first as an office boy for some prominent Brooklyn lawyers, who gave him a subscription to a circulating library, where his self-education began. Always an autodidact, Whitman absorbed an eclectic but wide-ranging education through his visits to museums, his nonstop reading, and his penchant for engaging everyone he met in conversation and debate. While most other major writers of his time enjoyed highly structured, classical educations at private institutions, Whitman forged his own rough and informal curriculum of literature, theater, history, geography, music, and archeology out of the developing public resources of America's fastest growing city.In 1831, Whitman became an apprentice on the Long Island Patriot, a liberal, working-class newspaper, where he learned the printing trade and was first exposed to the excitement of putting words into print, observing how thought and event could be quickly transformed into language and immediately communicated to thousands of readers. At the age of twelve, young Walt was already contributing to the newspaper and experiencing the exhilaration of getting his own words published. Whitman's first signed article, in the upscale New York Mirror in 1834, expressed his amazement at how there were still people alive who could remember "the present great metropolitan city as a little dorp or village; all fresh and green as it was, from its beginning," and he wrote of a slave, "Negro Harry," who had died in 1758 at age 120 and who could remember New York "when there were but three houses in it." Even late in his life, he could still recall the excitement of seeing this first article in print: "How it made my heart double-beat to see my piece on the pretty white paper, in nice type." For his entire life, he would maintain this fascination with the materiality of printed objects, with the way his voice and identity could be embodied in type and paper.

Living away from home—the rest of his family moved back to the West Hills area in 1833, leaving fourteen-year-old Walt alone in the city—and learning how to set type under the Patriot's foreman printer William Hartshorne, Whitman was gaining skills and experiencing an independence that would mark his whole career: he would always retain a typesetter's concern for how his words looked on a page, what typeface they were dressed in, what effects various spatial arrangements had, and he would always retain his stubborn independence, never marrying and living alone for most of his life. These early years on his own in Brooklyn and New York remained a formative influence on his writing, for it was during this time that he developed the habit of close observation of the ever-shifting panorama of the city, and a great deal of his journalism, poetry, and prose came to focus on catalogs of urban life and the history of New York City, Brooklyn, and Long Island.

Walt's brother Thomas Jefferson, known to everyone in the family as "Jeff," was born during the summer of 1833, soon after his family had resettled on a farm and only weeks after Walt had joined the crowds in Brooklyn that warmly welcomed the newly re-elected president, Andrew Jackson. Brother Jeff, fourteen years younger than Walt, would become the sibling he felt closest to, their bond formed when they traveled together to New Orleans in 1848, when Jeff was about the same age as Walt was when Jeff was born. But while Jeff was a young child, Whitman spent little time with him. Walt remained separated from his family and furthered his education by absorbing the power of language from a variety of sources: various circulating libraries (where he read Sir Walter Scott, James Fenimore Cooper, and other romance novelists), theaters (where he fell in love with Shakespeare's plays and saw Junius Booth, John Wilkes Booth's father, play the title role in Richard III, always Whitman's favorite play), and lectures (where he heard, among others, Frances Wright, the Scottish radical emancipationist and women's rights advocate). By the time he was sixteen, Walt was a journeyman printer and compositor in New York City. His future career seemed set in the newspaper and printing trades, but then two of New York's worst fires wiped out the major printing and business centers of the city, and, in the midst of a dismal financial climate, Whitman retreated to rural Long Island, joining his family at Hempstead in 1836. As he turned 17, the five-year veteran of the printing trade was already on the verge of a career change.

Schoolteaching Years

His unlikely next career was that of a teacher. Although his own formal education was, by today's standards, minimal, he had developed as a newspaper apprentice the skills of reading and writing, more than enough for the kind of teaching he would find himself doing over the next few years. He knew he did not want to become a farmer, and he rebelled at his father's attempts to get him to work on the new family farm. Teaching was therefore an escape but was also clearly a job he was forced to take in bad economic times, and some of the unhappiest times of his life were these five years when he taught school in at least ten different Long Island towns, rooming in the homes of his students, teaching three-month terms to large and heterogeneous classes (some with over eighty students, ranging in age from five to fifteen, for up to nine hours a day), getting very little pay, and having to put up with some very unenlightened people. After the excitement of Brooklyn and New York, these often isolated Long Island towns depressed Whitman, and he recorded his disdain for country people in a series of letters (not discovered until the 1980s) that he wrote to a friend named Abraham Leech: "Never before have I entertained so low an idea of the beauty and perfection of man's nature, never have I seen humanity in so degraded a shape, as here," he wrote from Woodbury in 1840: "Ignorance, vulgarity, rudeness, conceit, and dulness are the reigning gods of this deuced sink of despair."The little evidence we have of his teaching (mostly from short recollections by a few former students) suggests that Whitman employed what were then progressive techniques—encouraging students to think aloud rather than simply recite, refusing to punish by paddling, involving his students in educational games, and joining his students in baseball and card games. He did not hesitate to use his own poems—which he was by this time writing with some frequency, though they were rhymed, conventional verses that indicated nothing of the innovative poetry to come—as texts in his classroom. While he would continue to write frequently about educational issues and would always retain a keen interest in how knowledge is acquired, he was clearly not suited to be a country teacher. One of the poems in his first edition of Leaves of Grass, eventually called "There Was a Child Went Forth," can be read as a statement of Whitman's educational philosophy, celebrating unrestricted extracurricular learning, an openness to experience and ideas that would allow for endless absorption of variety and difference: this was the kind of education Whitman had given himself and the kind he valued. He would always be suspicious of classrooms, and his great poem "Song of Myself" is generated by a child's wondering question, "What is the grass?," a question that Whitman spends the rest of the poem ruminating about as he discovers the complex in the seemingly simple, the cosmos in himself—an attitude that is possible, he says, only when we put "creeds and schools in abeyance." He kept himself alive intellectually by taking an active part in debating societies and in political campaigns: inspired by the Scottish reformist Frances Wright, who came to the United States to support Martin Van Buren in the presidential election of 1836, Whitman became an industrious worker for the Democratic party, campaigning hard for Martin Van Buren's successful candidacy.

By 1841, Whitman's second career was at an end. He had interrupted his teaching in 1838 to try his luck at starting his own newspaper, The Long Islander, devoted to covering the towns around Huntington. He bought a press and type and hired his younger brother George as an assistant, but, despite his energetic efforts to edit, publish, write for, and deliver the new paper, it folded within a year, and he reluctantly returned to the classroom. Newspaper work made him happy, but teaching did not, and two years later, he abruptly quit his job as an itinerant schoolteacher. The reasons for his decision continue to interest biographers. One persistent but unsubstantiated rumor has it that Whitman committed sodomy with one of his students while teaching in Southold, though it is not possible to prove that Whitman actually even taught there. The rumor suggests he was run out of town in disgrace, never to return and soon to abandon teaching altogether. But in fact Whitman did travel again to Southold, writing some remarkably unperturbed journalistic pieces about the place in the late 1840s and early 1860s. It seems far more likely that Whitman gave up schoolteaching because he found himself temperamentally unsuited for it. And, besides, he had a new career opening up: he decided now to become a fiction writer. Best of all, to nurture that career, he would need to return to New York City and re-establish himself in the world of journalism.

Whitman the Fiction Writer

How ambitious was Whitman as a writer of short fiction? The evidence suggests that he was definitely more than a casual dabbler and that he threw himself energetically into composing stories. Still, he did not give himself over to fiction with the kind of life-changing commitment he would later give to experimental poetry. He was adding to his accomplishments, moving beyond being a respectable journalist and developing literary talents and aspirations. About twenty different newspapers and magazines printed Whitman's fiction and early poetry. His best years for fiction were between 1840 and 1845 when he placed his stories in a range of magazines, including the American Review (later called the American Whig Review ) and the Democratic Review, one of the nation's most prestigious literary magazines. As a writer of fiction, he lacked the impulse toward innovation and the commitment to self-training that later moved him toward experimental verse, even though we can trace in his fiction some of the themes that would later flourish in Leaves of Grass.His early stories are captivating in large part because they address obliquely (not to say crudely) important professional and psychological matters. His first published story, "Death in the School-Room," grew out of his teaching experience and interjected direct editorializing commentary: the narrator hopes that the "many ingenious methods of child-torture will [soon] be gaz'd upon as a scorned memento of an ignorant, cruel, and exploded doctrine." This tale had a surprise ending: the teacher flogs a student he thinks is sleeping only to make the macabre discovery that he has been beating a corpse. Another story, "The Shadow and the Light of a Young Man's Soul," offered a barely fictionalized account of Whitman's own circumstances and attitudes: the hero, Archibald Dean, left New York because of the great fire to take charge of a small district school, a move that made him feel "as though the last float-plank which buoyed him up on hope and happiness, was sinking, and he with it." Other stories concern themselves with friendships between older and younger men (especially younger men who are weak or in need of defense since they are misunderstood and at odds with figures of authority).

Whitman's steady stream of stories in the Democratic Review in 1842—he published five between January and September—must have made Park Benjamin, editor of the New World, conclude that Whitman was the perfect candidate to write a novel that would speak to the booming temperance movement. Whitman had earlier worked for Benjamin as a printer, and the two had quarreled, leading Whitman to write "Bamboozle and Benjamin," an article attacking this irascible editor whose practice of rapidly printing advance copies of novels, typically by English writers, threatened both the development of native writers and the viability of U.S. publishing houses. But now both men were willing to overlook past differences in order to seize a good financial opportunity.

In an extra number in November 1842, Benjamin's New World published Whitman's Franklin Evans; or The Inebriate. The novel centers on a country boy who, after falling prey to drink in the big city, eventually causes the death of three women. The plot, which ends in a conventional moralistic way, was typical of temperance literature in allowing sensationalism into literature under a moral guise. Whitman's treatment of romance and passion here, however, is unpersuasive and seems to confirm a remark he had made two years earlier that he knew nothing about women either by "experience or observation." The novel stands nonetheless as one of the earliest explorations in American literature of the theme of miscegenation, and its treatment of the enslaved (white) body, captive to drink, has resonance, as does the novel's fascination with "fatal pleasure," Evans's name for the strong attraction most men feel for sinful experience, be it drink or sex.

Interestingly, Franklin Evans sold more copies (approximately 20,000) than anything else Whitman published in his lifetime. The work succeeded despite being a patched-together concoction of new writing and previously composed stories. Whitman claimed he completed Franklin Evans in three days and that he composed parts of the novel in the reading room of Tammany Hall, inspired by gin cocktails (another time he claimed he was buoyed by a bottle of port.) He eventually described Franklin Evans as "damned rot—rot of the worst sort." Despite these old-age remarks, Whitman's original purpose was serious, for he supported temperance consistently in the 1840s, including in two tales—"Wild Frank's Return" and the "The Child's Champion"—that turn on the consequences of excessive drinking. Moreover, Whitman began another temperance novel (The Madman) within months of finishing Franklin Evans, though he soon abandoned the project. His concern with the temperance issue may have derived from his father's drinking habits or even from Whitman's own drinking tendencies when he was an unhappy schoolteacher. Whatever the source, Whitman's concern with the issue remained throughout his career, and his poetry records, again and again, the waste of alcoholic abuse, the awful "law of drunkards" that produces "the livid faces of drunkards," "those drunkards and gluttons of so many generations," the "drunkard's breath," the "drunkard's stagger," "the old drunkard staggering home."

Itinerant Journalist

During the time he was writing temperance fiction, Whitman remained a generally successful journalist. He cultivated a fashionable appearance: William Cauldwell, an apprentice who knew him as lead editor at the New York Aurora, said that Whitman "usually wore a frock coat and high hat, carried a small cane, and the lapel of his coat was almost invariably ornamented with a boutonniere." In 1842 and 1843 he moved easily in and out of positions (as was then common among journalists) on an array of newspapers, including, in addition to the Aurora, the New York Evening Tattler, the New York Statesman, and the New York Sunday Times. And he wrote on topics ranging from criticizing how the police rounded up prostitutes to denouncing Bishop John Hughes for his effort to use public funds to support parochial schools.Whitman left New York in 1845, perhaps because of financial uncertainty resulting from his fluctuating income. He returned to Brooklyn and to steadier work in a somewhat less competitive journalistic environment. Often regarded as a New York City writer, his residence and professional career in the city actually ended, then, a full decade before the first appearance of Leaves of Grass. However, even after his move to Brooklyn, he remained connected to New York: he shuttled back and forth via the Fulton ferry, and he drew imaginatively on the city's rich and varied splendor for his subject matter.

Opera Lover

Opera was one of the many attractions that encouraged Whitman's frequent returns to New York. In 1846 Whitman began attending performances (often with his brother Jeff), a practice that was disrupted only by the onset of the Civil War (and even during the war, he managed to attend operas whenever he got back to New York). Whitman loved the thought of the human body as its own musical instrument, and his fascination with voice would later manifest itself in his desire to be an orator and in his frequent inclusion of oratorical elements in his poetry. For Whitman, listening to opera had the intensity of a "love-grip." In particular, the great coloratura soprano, Marietta Alboni, sent him into raptures: throughout his life she would remain his standard for great operatic performance, and his poem "To a Certain Cantatrice" addresses her as the equal of any hero. Whitman once said, after attending an opera, that the experience was powerful enough to initiate a new era in a person's development. When he later composed a poem describing his dawning sense of vocation ("Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking"), opera provided both structure and contextual clues to meaning.Mature Journalist

By the mid-1840s, Whitman had a keen awareness of the cultural resources of New York City and probably had more inside knowledge of New York journalism than anyone else in Brooklyn. The Long Island Star recognized his value as a journalist and, once he resettled in Brooklyn, quickly arranged to have him compose a series of editorials, two or three a week, from September 1845 to March 1846. With the death of William Marsh, the editor of the Brooklyn Eagle, Whitman became chief editor of that paper (he served from March 5, 1846 to January 18, 1848). He dedicated himself to journalism in these years and published little of his own poetry and fiction. However, he introduced literary reviewing to the Eagle, and he commented, if often superficially, on writers such as Carlyle and Emerson, who in the next decade would have a significant impact on Leaves of Grass. The editor's role gave Whitman a platform from which to comment on various issues from street lighting to politics, from banking to poetry. But Whitman claimed that what he most valued was not the ability to promote his opinions, but rather something more intimate, the "curious kind of sympathy . . . that arises in the mind of a newspaper conductor with the public he serves. He gets to love them."For Whitman, to serve the public was to frame issues in accordance with working class interests—and for Whitman this usually meant white working class interests. He sometimes dreaded slave labor as a "black tide" that could overwhelm white workingmen. He was adamant that slavery should not be allowed into the new western territories because he feared whites would not migrate to an area where their own labor was devalued unfairly by the institution of black slavery. Periodically, Whitman expressed outrage at practices that furthered slavery itself: for example, he was incensed at laws that made possible the importation of slaves by way of Brazil. Like Lincoln, he consistently opposed slavery and its further extension, even while he knew (again like Lincoln) that the more extreme abolitionists threatened the Union itself. In a famous incident, Whitman lost his position as editor of the Eagle because the publisher, Isaac Van Anden, as an "Old Hunker," sided with conservative pro-slavery Democrats and could no longer abide Whitman's support of free soil and the Wilmot Proviso (a legislative proposal designed to stop the expansion of slavery into the western territories).

New Orleans Sojourn

Fortunately, on February 9, 1848, Whitman met, between acts of a performance at the Broadway Theatre in New York, J. E. McClure, who intended to launch a New Orleans paper, the Crescent, with an associate, A. H. Hayes. In a stunningly short time—reportedly in fifteen minutes—McClure struck a deal with Whitman and provided him with an advance to cover his travel expenses to New Orleans. Whitman's younger brother Jeff , then only fifteen years old, decided to travel with Walt and work as an office boy on the paper. The journey—by train, steamboat, and stagecoach—widened Walt's sense of the country's scope and diversity, as he left the New York City and Long Island area for the first time. Once in New Orleans, Walt did not have the famous New Orleans romance with a beautiful Creole woman, a relationship first imagined by the biographer Henry Bryan Binns and further elaborated by others who were charmed by the city's exoticism and who were eager to identify heterosexual desires in the poet. The published versions of his New Orleans poem called "Once I Pass'd Through a Populous City" seem to recount a romance with a woman, though the original manuscript reveals that he initially wrote with a male lover in mind.Whatever the nature of his personal attachments in New Orleans, he certainly encountered a city full of color and excitement. He wandered the French quarter and the old French market, attracted by "the Indian and negro hucksters with their wares" and the "great Creole mulatto woman" who sold him the best coffee he ever tasted. He enjoyed the "splendid and roomy bars" (with "exquisite wines, and the perfect and mild French brandy") that were packed with soldiers who had recently returned from the war with Mexico, and his first encounters with young men who had seen battle, many of them recovering from war wounds, occurred in New Orleans, a precursor of his Civil War experiences. He was entranced by the intoxicating mix of languages—French and Spanish and English—in that cosmopolitan city and began to see the possibilities of a distinctive American culture emerging from the melding of races and backgrounds (his own fondness for using French terms may well have derived from his New Orleans stay). But the exotic nature of the Southern city was not without its horrors: slaves were auctioned within an easy walk of where the Whitman brothers were lodging at the Tremont House, around the corner from Lafayette Square. Whitman never forgot the experience of seeing humans on the selling block, and he kept a poster of a slave auction hanging in his room for many years as a reminder that such dehumanizing events occurred regularly in the United States. The slave auction was an experience that he would later incorporate in his poem "I Sing the Body Electric."

Walt felt wonderfully healthy in New Orleans, concluding that it agreed with him better than New York, but Jeff was often sick with dysentery, and his illness and homesickness contributed to their growing desire to return home. The final decision, though, was taken out of the hands of the brothers, as the Crescent owners exhibited what Whitman called a "singular sort of coldness" toward their new editor. They probably feared that this northern editor would embarrass them because of his unorthodox ideas, especially about slavery. Whitman's sojourn in New Orleans lasted only three months.

Budding Poet

His trip South produced a few lively sketches of New Orleans life and at least one poem, "Sailing the Mississippi at Midnight," in which the steamboat journey becomes a symbolic journey of life:

Vast and starless, the pall of heaven

Laps on the trailing pall below;

And forward, forward, in solemn darkness,

As if to the sea of the lost we go.Throughout much of the 1840s Whitman wrote conventional poems like this one, often echoing Bryant, and, at times, Shelley and Keats. Bryant—and the graveyard school of English poetry—probably had the most important impact on his sensibility, as can be seen in his pre-Leaves of Grass poems "Our Future Lot," "Ambition," "The Winding-Up," "The Love that is Hereafter," and "Death of the Nature-Lover." The poetry of these years is artificial in diction and didactic in purpose; Whitman rarely seems inspired or innovative. Instead, tired language usually renders the poems inert. By the end of the decade, however, Whitman had undertaken serious self-education in the art of poetry, conducted in a typically unorthodox way—he clipped essays and reviews about leading British and American writers, and as he studied them he began to be a more aggressive reader and a more resistant respondent. His marginalia on these articles demonstrate that he was learning to write not in the manner of his predecessors but against them.

The mystery about Whitman in the late 1840s is the speed of his transformation from an unoriginal and conventional poet into one who abruptly abandoned conventional rhyme and meter and, in jottings begun at this time, exploited the odd loveliness of homely imagery, finding beauty in the commonplace but expressing it in an uncommon way. What is known as Whitman's earliest notebook (called "albot Wilson" in the Notebooks and Unpublished Prose Manuscripts) was long thought to date from 1847 but is now understood to be from about 1854. This extraordinary document contains early articulations of some of Whitman's most compelling ideas. Famous passages on "Dilation," on "True noble expanding American character," and on the "soul enfolding orbs" are memorable prose statements that express the newly expansive sense of self that Whitman was discovering, and we find him here creating the conditions—setting the tone and articulating the ideas—that would allow for the writing of Leaves of Grass.

On July 16, 1849, the publisher, health guru, and social reformer Lorenzo Fowler confirmed Whitman's growing sense of personal capacity when his phrenological analysis of the poet's head led to a flattering—and in some ways quite accurate—description of his character. In addition to bolstering Whitman's confidence, the reading of the "bumps" on his skull gave him some key vocabulary (like "amativeness" and "adhesiveness," phrenological terms delineating affections between and among the sexes) for Leaves of Grass. Whitman's association with Lorenzo Fowler and his brother Orson would prove to be of continuing importance well into the 1850s. The Fowler brothers distributed the first edition of Leaves of Grass, published the second anonymously, and provided a venue in their firm's magazine for one of Whitman's self-reviews.

Racial Politics and the Origins of Leaves of Grass

A pivotal and empowering change came over Whitman at this time of poetic transformation. His politics—and especially his racial attitudes—underwent a profound alteration. As we have noted, Whitman the journalist spoke to the interests of the day and from a particular class perspective when he advanced the interests of white workingmen while seeming, at times, unconcerned about the plight of blacks. Perhaps the New Orleans experience had prompted a change in attitude, a change that was intensified by an increasing number of friendships with radical thinkers and writers who led Whitman to rethink his attitudes toward the issue of race. Whatever the cause, in Whitman's future-oriented poetry blacks become central to his new literary project and central to his understanding of democracy. Notebook passages assert that the poet has the "divine grammar of all tongues, and says indifferently and alike How are you friend? to the President in the midst of his cabinet, and Good day my brother, to Sambo among the hoes of the sugar field."It appears that Whitman's increasing frustration with the Democratic party's compromising approaches to the slavery crisis led him to continue his political efforts through the more subtle and indirect means of experimental poetry, a poetry that he hoped would be read by masses of average Americans and would transform their way of thinking. In any event, his first notebook lines in the manner of Leaves of Grass focus directly on the fundamental issue dividing the United States. His notebook breaks into free verse for the first time in lines that seek to bind opposed categories, to link black and white, to join master and slave:

I am the poet of the body

And I am the poet of the soul

I go with the slaves of the earth equally with the masters

And I will stand between the masters and the slaves,

Entering into both so that both shall understand me alike.

The audacity of that final line remains striking. While most people were lining up on one side or another, Whitman placed himself in that space—sometimes violent, sometimes erotic, always volatile—between master and slave. His extreme political despair led him to replace what he now named the "scum" of corrupt American politics in the 1850s with his own persona—a shaman, a culture-healer, an all-encompassing "I."The American "I"

That "I" became the main character of Leaves of Grass, the explosive book of twelve untitled poems that he wrote in the early years of the 1850s, and for which he set some of the type, designed the cover, and carefully oversaw all the details. When Whitman wrote "I, now thirty-six years old, in perfect health, begin," he announced a new identity for himself, and his novitiate came at an age quite advanced for a poet. Keats by that age had been dead for ten years; Byron had died at exactly that age; Wordsworth and Coleridge produced Lyrical Ballads while both were in their twenties; Bryant had written "Thanatopsis," his best-known poem, at age sixteen; and most other great Romantic poets Whitman admired had done their most memorable work early in their adult lives. Whitman, in contrast, by the time he had reached his mid-thirties, seemed destined, if he were to achieve fame in any field, to do so as a journalist or perhaps as a writer of fiction, but no one could have guessed that this middle-aged writer of sensationalistic fiction and sentimental verse would suddenly begin to produce work that would eventually lead many to view him as America's greatest and most revolutionary poet.The mystery that has intrigued biographers and critics over the years has been about what prompted the transformation: did Whitman undergo some sort of spiritual illumination that opened the floodgates of a radical new kind of poetry, or was this poetry the result of an original and carefully calculated strategy to blend journalism, oratory, popular music, and other cultural forces into an innovative American voice like the one Ralph Waldo Emerson had called for in his essay "The Poet"? "Our log-rolling, our stumps and their politics, our fisheries, our Negroes, and Indians, our boasts, and our repudiations, the wrath of rogues, and the pusillanimity of honest men, the Northern trade, the Southern planting, the Western clearing, Oregon and Texas, are yet unsung," wrote Emerson; "Yet America is a poem in our eyes; its ample geography dazzles the imagination, and it will not wait long for metres." Whitman began writing poetry that seemed, wildly yet systematically, to record every single thing that Emerson called for, and he began his preface to the 1855 Leaves by paraphrasing Emerson: "The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem." The romantic view of Whitman is that he was suddenly inspired to impulsively write the poems that transformed American poetry; the more pragmatic view holds that Whitman devoted himself in the five years before the first publication of Leaves to a disciplined series of experiments that led to the gradual and intricate structuring of his singular style. Was he truly the intoxicated poet Emerson imagined or was he the architect of a poetic persona that cleverly mimicked Emerson's description?

There is evidence to support both theories. We know very little about the details of Whitman's life in the early 1850s; it is as if he retreated from the public world to receive inspiration, and there are relatively few remaining manuscripts of the poems in the first edition of Leaves, leading many to believe that they emerged in a fury of inspiration. On the other hand, the manuscripts that do remain indicate that Whitman meticulously worked and reworked passages of his poems, heavily revising entire drafts of the poems, and that he issued detailed instructions to the Rome brothers, the printers who were setting his book in type, carefully overseeing every aspect of the production of his book.

Whitman seems, then, to have been both inspired poet and skilled craftsman, at once under the spell of his newly discovered and intoxicating free verse style while also remaining very much in control of it, adjusting and altering and rearranging. For the rest of his life, he would add, delete, fuse, separate, and rearrange poems as he issued six very distinct editions of Leaves of Grass. Emerson once described Whitman's poetry as "a remarkable mixture of the Bhagvat Ghita and the New York Herald," and that odd joining of the scriptural and the vernacular, the transcendent and the mundane, effectively captures the quality of Whitman's work, work that most readers experience as simultaneously magical and commonplace, sublime and prosaic. It was work produced by a poet who was both sage and huckster, who touched the gods with ink-smudged fingers, and who was concerned as much with the sales and reviews of his book as with the state of the human soul.

The First Edition of Leaves of Grass

Whitman paid out of his own pocket for the production of the first edition of his book and had only 795 copies printed, which he bound at various times as his finances permitted. He always recalled the book as appearing, fittingly, on the Fourth of July, as a kind of literary Independence Day. His joy at getting the book published was quickly diminished by the death of his father within a week of the appearance of Leaves. Walter Sr. had been ill for several years, and though he and Walt had never been particularly close, they had only recently traveled together to West Hills, Long Island, to the old Whitman homestead where Walt was born. Now his father's death along with his older brother Jesse's absence as a merchant marine (and later Jesse's growing violence and mental instability) meant that Walt would become the father-substitute for the family, the person his mother and siblings would turn to for help and guidance. He had already had some experience enacting that role even while Walter Sr. was alive; perhaps because of Walter Sr.'s drinking habits and growing general depression, young Walt had taken on a number of adult responsibilities—buying boots for his brothers, for instance, and holding the title to the family house as early as 1847. Now, however, he became the only person his mother and siblings could turn to.But even given these growing family burdens, he managed to concentrate on his new book, and, just as he oversaw all the details of its composition and printing, so now did he supervise its distribution and try to control its reception. Even though Whitman claimed that the first edition sold out, the book in fact had very poor sales. He sent copies to a number of well-known writers (including John Greenleaf Whittier, who, legend has it, threw his copy in the fire), but only one responded, and that, fittingly, was Emerson, who recognized in Whitman's work the very spirit and tone and style he had called for. "I greet you at the beginning of a great career," Emerson wrote in his private letter to Whitman, noting that Leaves of Grass "meets the demand I am always making of what seemed the sterile and stingy nature, as if too much handiwork, or too much lymph in the temperament, were making our western wits fat and mean." Whitman's was poetry that would literally get the country in shape, Emerson believed, give it shape, and help work off its excess of aristocratic fat.

Whitman's book was an extraordinary accomplishment: after trying for over a decade to address in journalism and fiction the social issues (such as education, temperance, slavery, prostitution, immigration, democratic representation) that challenged the new nation, Whitman now turned to an unprecedented form, a kind of experimental verse cast in unrhymed long lines with no identifiable meter, the voice an uncanny combination of oratory, journalism, and the Bible—haranguing, mundane, and prophetic—all in the service of identifying a new American democratic attitude, an absorptive and accepting voice that would catalog the diversity of the country and manage to hold it all in a vast, single, unified identity. "Do I contradict myself?" Whitman asked confidently toward the end of the long poem he would come to call "Song of Myself": "Very well then . . . . I contradict myself; / I am large . . . . I contain multitudes." This new voice spoke confidently of union at a time of incredible division and tension in the culture, and it spoke with the assurance of one for whom everything, no matter how degraded, could be celebrated as part of itself: " What is commonest and cheapest and nearest and easiest is Me." His work echoed with the lingo of the American urban working class and reached deep into the various corners of the roiling nineteenth-century culture, reverberating with the nation's stormy politics, its motley music, its new technologies, its fascination with science, and its evolving pride in an American language that was forming as a tongue distinct from British English.

Though it was no secret who the author of Leaves of Grass was, the fact that Whitman did not put his name on the title page was an unconventional and suggestive act (his name would in fact not appear on a title page of Leaves until the 1876 "Author's Edition" of the book, and then only when Whitman signed his name on the title page as each book was sold). The absence of a name indicated, perhaps, that the author of this book believed he spoke not for himself so much as for America. But opposite the title page was a portrait of Whitman, an engraving made from a daguerreotype that the photographer Gabriel Harrison had made during the summer of 1854. It has become the most famous frontispiece in literary history, showing Walt in workman's clothes, shirt open, hat on and cocked to the side, standing insouciantly and fixing the reader with a challenging stare. It is a full-body pose that indicates Whitman's re-calibration of the role of poet as the democratic spokesperson who no longer speaks only from the intellect and with the formality of tradition and education: the new poet pictured in Whitman's book is a poet who speaks from and with the whole body and who writes outside, in Nature, not in the library. It was what Whitman called "al fresco" poetry, poetry written outside the walls, the bounds, of convention and tradition.

The 1856 Leaves

Within a few months of producing his first edition of Leaves, Whitman was already hard at work on the second edition. While in the first, he had given his long lines room to stretch across the page by printing the book on large paper, in the second edition he sacrificed the spacious pages and produced what he later called his "chunky fat book," his earliest attempt to create a pocket-size edition that would offer the reader what Whitman thought of as the "ideal pleasure"—"to put a book in your pocket and [go] off to the seashore or the forest." On the cover of this edition, published and distributed by Fowler and Wells (though the firm carefully distanced themselves from the book by proclaiming that "the author is still his own publisher"), Whitman emblazoned one of the first "blurbs" in American publishing history: without asking Emerson's permission, he printed in gold on the spine of the book the opening words of Emerson's letter to him: "I greet you at the beginning of a great career," followed by Emerson's name. And, to generate publicity for the volume, he appended to the volume a group of reviews of the first edition—including three he wrote himself along with a few negative reviews—and called the gathering Leaves-Droppings. Whitman was a pioneer of the "any publicity is better than no publicity" strategy. At the back of the book, he printed Emerson's entire letter (again, without permission) and wrote a long public letter back—a kind of apologia for his poetry—addressing it to "Master." Although he would later downplay the influence of Emerson on his work, at this time, he later recalled, he had "Emerson-on-the-brain."With four times as many pages as the first edition, the 1856 Leaves added twenty new poems (including the powerful "Sun-Down Poem," later called "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry") to the original twelve in the 1855 edition. Those original twelve had been untitled in 1855, but Whitman was doing all he could to make the new edition look and feel different: small pages instead of large, a fat book instead of a thin one, and long titles for his poems instead of none at all. So the untitled introductory poem from the first edition that would eventually be named "Song of Myself" was in 1856 called "Poem of , an American," and the poem that would become "This Compost" appeared here as "Poem of Wonder at the Resurrection of The Wheat." Some titles seemed to challenge the very bounds of titling by incorporating rolling catalogs like the poems themselves: "To a Foil'd European Revolutionaire" appeared as "Liberty Poem for Asia, Africa, Europe, America, Australia, Cuba, and The Archipelagoes of the Sea." As if to counter some of the early criticism that he was not really writing poetry at all—the review in Life Illustrated, for example, called Whitman's work "lines of rhythmical prose, or a series of utterances (we know not what else to call them)"—Whitman put the word "Poem" in the title of all thirty-two works in the 1856 Leaves. Like them or not, Whitman seemed to be saying, they are poems, and more and more of them were on the way. But, despite his efforts to re-make his book, the results were depressingly the same: sales of the thousand copies that were printed were even poorer than for the first edition.

The Bohemian Years

In these years, Whitman was in fact working hard at becoming a poet by forging literary connections: he entered the literary world in a way he never had as a fiction writer or journalist, meeting some of the nation's best-known writers, beginning to socialize with a literary and artistic crowd, and cultivating an image as an artist. Emerson had come to visit Whitman at the end of 1855 (they went back to Emerson's room at the elegant Astor Hotel, where Whitman—dressed as informally as he was in his frontispiece portrait—was denied admission); this was the first of many meetings the two would have over the next twenty-five years, as their relationship turned into one of grudging respect for each other mixed with mutual suspicion. The next year, Henry David Thoreau and Bronson Alcott visited Whitman's home (Alcott described Thoreau and Whitman as each "surveying the other curiously, like two beasts, each wondering what the other would do"). Whitman also came to befriend a number of visual artists, like the sculptor Henry Kirke Brown, the painter Elihu Vedder, and the photographer Gabriel Harrison. And he came to know a number of women's rights activists and writers, some of whom became ardent readers and supporters of Leaves of Grass. He became particularly close to Abby Price, Paulina Wright Davis, Sarah Tyndale, and Sara Payson Willis (who, under the pseudonym Fanny Fern wrote a popular newspaper column and many popular books, including Fern Leaves from Fanny' s Portfolio [1853], the cover of which Whitman imitated for his first edition of Leaves). These women's radical ideas about sexual equality had a growing impact on Whitman's poetry. He knew a number of abolitionist writers at this time, including Moncure Conway, and Whitman wrote some vitriolic attacks on the fugitive slave law and the moral bankruptcy of American politics, but these pieces (notably "The Eighteenth Presidency!") were never published and remain vestiges of yet another career—stump speaker, political pundit—that Whitman flirted with but never pursued.Whitman also began in the late 1850s to become a regular at Pfaff's saloon, a favorite hangout for bohemian artists in New York. Whitman had worked for a couple of years for the Brooklyn Daily Times, a Free Soil newspaper, until the middle of 1859, when, once again, a disagreement with the newspaper's owner led to his dismissal. At Pfaff's, Whitman the former temperance writer began a couple of years of unemployed carousing; he was clearly remaking his image, going to bars more often than he had since he left New Orleans a decade earlier. At Pfaff's, he mingled with figures like Henry Clapp, the influential editor of the anti-establishment Saturday Press who would help publicize Whitman's work in many ways, including publishing in 1859 an early version of "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking." Whitman also became friends at Pfaff's with many writers, some well known at the time: Ada Clare, Fitz-James O'Brien, George Arnold, and Edmund Clarence Stedman. It was here, too, that a young William Dean Howells met Whitman; Howells recalled this meeting many years later, when he made it clear that Whitman had already by the time of their meeting become something of a celebrity, even if his fame was largely the infamy resulting from what many considered to be his obscene writings ("foul work" filled with "libidinousness," scolded The Christian Examiner). Whitman and Ada Clare, known as the "queen of Bohemia" (she had an illegitimate child and proudly proclaimed herself an unmarried mother), became two of the most notorious figures at the beer hall, flouting convention and decorum.

It was at Pfaff's, too, that Whitman joined the "Fred Gray Association," a loose confederation of young men who seemed anxious to explore new possibilities of male-male affection. It may have been at Pfaff's that Whitman met Fred Vaughan, an intriguing mystery-figure in Whitman biography. Whitman and Vaughan, a young Irish stage driver, clearly had an intense relationship at this time, perhaps inspiring the sequence of homoerotic love poems Whitman called "Live Oak, with Moss," poems that would become the heart of his Calamus cluster, which appeared in the 1860 edition of Leaves. These poems record a despair about the failure of the relationship, and the loss of Whitman's bond with Vaughan—who soon married, had four children, and would only sporadically keep in touch with Whitman—was clearly the source of some deep unhappiness for the poet.

1860 Edition of Leaves

Whitman's re-made self-image is evident on the frontispiece of the new edition of Leaves that appeared in 1860. It would be the only time Whitman used this portrait, an engraving based on a painting done by Whitman's artist friend Charles Hine. Whitman's friends called it the "Byronic portrait," and Whitman does look more like the conventional image of a poet—with coiffure and cravat—than he ever did before or after. This is the portrait of an artist who has devoted significant time to his image and one who has also clearly enjoyed his growing notoriety among the arty crowd at Pfaff's.Ever since the 1856 edition appeared, Whitman had been writing poems at a furious pace; within a year of the 1856 edition's appearance, he wrote nearly seventy new poems. He continued to have them set in type by the Rome brothers and other printer friends, as if he assumed that he would inevitably be publishing them himself, since no commercial publisher had indicated an interest in his book. But there was another reason Whitman set his poems in type: he always preferred to deal with his poems in printed form instead of in manuscript. He often would revise directly on printed versions of his poetry; for him, poetry was very much a public act, and until the poem was in print he did not truly consider it a poem. Poetic manuscripts were never sacred objects for Whitman, who often simply discarded them; getting the poem set in type was the most important step in allowing it to begin to do its cultural work.

In 1860, while the nation seemed to be moving inexorably toward a major crisis between the slaveholding and free states, Whitman's poetic fortunes took a positive turn. In February, he received a letter from the Boston publishers William Thayer and Charles Eldridge, whose aggressive new publishing house specialized in abolitionist literature; they wanted to become the publishers of the new edition of Leaves of Grass. Whitman, feeling confirmed as an authentic poet now that he had been offered actual royalties, readily agreed, and Thayer and Eldridge invested heavily in the stereotype plates for Whitman's idiosyncratic book—over 450 pages of varied typeface and odd decorative motifs, a visually chaotic volume all carefully tended to by Whitman, who traveled to Boston to oversee the printing.

This was Whitman's first trip to Boston, then considered the literary capital of the nation. Whitman is a major part of the reason that America's literary center moved from Boston to New York in the second half of the nineteenth century, but in 1860 the superior power of Boston was still evident in its influential publishing houses, its important journals (including the new Atlantic Monthly), and its venerable authors (including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, whom Whitman met briefly while in town) . And, of course, Boston was the city of Emerson, who came to see Whitman shortly after his arrival in the city in March. In one of the most celebrated meetings of major American writers, the Boston Brahmin and the Yankee rowdy strolled together on the Boston Common, while Emerson tried to convince Whitman to remove from his Boston edition the new Enfans d'Adam cluster of poems (after 1860, Whitman dropped the French version of the name and called the cluster Children of Adam), works that portrayed the human body more explicitly and in more direct sexual terms than any previous American poems. Whitman argued, as he later recalled, "that the sexual passion in itself, while normal and unperverted, is inherently legitimate, creditable, not necessarily an improper theme for poet." "That," insisted Whitman, "is what I felt in my inmost brain and heart, when I only answer'd Emerson's vehement arguments with silence, under the old elms of Boston Common." Emerson's caution notwithstanding, the body—the entire body—would be Whitman's theme, and he would not shy away from any part of it, not discriminate or marginalize or form hierarchies of bodily parts any more than he would of the diverse people making up the American nation. His democratic belief in the importance of all the parts of any whole, was central to his vision: the genitals and the arm-pits were as essential to the fullness of identity as the brain and the soul, just as, in a democracy, the poorest and most despised citizens were as important as the rich and famous. This, at any rate, was the theory of radical union and equality that generated Whitman's work.

So he ignored Emerson's advice and published the Children of Adam poems in the 1860 edition along with his Calamus cluster; the first cluster celebrated male-female sexual relations, and the second celebrated the love of men for men. The body remained very much Whitman's subject, but it was never separate from the body of the text, and he always set out not just to write about sensual embrace but also to enact the physical embrace of poet and reader. Whitman became a master of sexual politics, but his sexual politics were always intertwined with his textual politics. Leaves of Grass was not a book that set out to shock the reader so much as to merge with the reader and make him or her more aware of the body each reader inhabited, to convince us that the body and soul were conjoined and inseparable, just as Whitman's ideas were embodied in words that had physical body in the ink and paper that readers held physically in their hands. Ideas, Whitman's poems insist, pass from one person to another not in some ethereal process, but through the bodies of texts, through the muscular operations of tongues and hands and eyes, through the material objects of books.

Whitman was already well along on his radical program of delineating just what democratic affection would entail. He called his Calamus poems his most political work—"The special meaning of the Calamus cluster," Whitman wrote, "mainly resides in its Political significance"—since in those poems he was articulating a new kind of intense affection between males who, in the developing democratic society and emerging capitalistic system, were being encouraged to become fiercely competitive. Whitman countered this movement with a call for manly love, embrace, and affection. In giving voice to this new camaraderie, Whitman was also inventing a language of homosexuality, and the Calamus poems became very influential poems in the development of gay literature. In the nineteenth century, however, the Calamus poems did not cause as much sensation as Children of Adam because, even though they portrayed same-sex affection, they were only mildly sensual, evoking handholding, hugging, and kissing, while the Children of Adam poems evoked a more explicit genital sexuality. Emerson and others were apparently unfazed by Calamus and focused their disapprobation on Children of Adam. Only later in the century, when homosexuality began to be formulated in medical and psychological circles as an aberrant personality type, did the Calamus poems begin to be read by some as dangerous and "abnormal" and by others as brave early expressions of gay identity.

With the 1860 edition of Leaves, Whitman began the incessant rearrangement of his poems in various clusters and groupings. Whitman settled on cluster arrangements as the most effective way to organize his work, but his notion of particular clusters changed from edition to edition as he added, deleted, and rearranged his poems in patterns that often alter their meaning and recontextualize their significance. In addition to Calamus and Children of Adam, this edition contained clusters called Chants Democratic and Native American, Messenger Leaves, and another named the same as the book, Leaves of Grass. This edition also contained the first book printings of "Starting from Paumanok" (here called "Proto-Leaf") and "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking" (here called "A Word Out of the Sea"), along with over 120 other new poems. He also revised many of his other poems, including "Song of Myself" (here called simply ""), and throughout the book he numbered his poetic verses, creating a Biblical effect. This was no accident, since Whitman now conceived of his project as involving the construction of what he called a "New Bible," a new covenant that would convert America into a true democracy.

The 1860 edition sold fairly well, with the first printing of a thousand copies quickly exhausted and an additional printing (totaling at least a thousand and perhaps as many as three or four thousand more copies) promptly ordered by Thayer and Eldridge. The 1860 edition received many reviews, most of them positive, particularly those by women readers who, it seems, were more exhilarated than offended by Whitman's candid iimages of sex and the body, and who welcomed his language of equality between the sexes, his attempts to sing "The Female equally with the Male."

Whitman's time in Boston—the first extended period he had been away from New York since his trip to New Orleans twelve years earlier—was a transforming experience. He was surprised by the way African Americans were treated much more fairly and more as equals than was the case in New York, sharing tables with whites at eating houses, working next to whites in printing offices, and serving on juries. He also met a number of abolitionist writers who would soon become close friends and supporters, including William Douglas O'Connor and John Townsend Trowbridge, both of whom would later write at length about Whitman. When he returned to New York at the end of May, his mood was ebullient. He was now a recognized author; the Boston papers had run feature stories about his visit to the city, and photographers had asked to photograph him (not only did he have a growing notoriety, he was a striking physical specimen at over six feet in height—especially tall for the time—with long, already graying hair and beard). All summer long he read reviews of his work in prominent newspapers and journals. And in November, Whitman's young publishers announced that Whitman's new project, a book of poems he called Banner at Day-Break, would be forthcoming.

The Beginning of the Civil War

But just as suddenly as Whitman's fortunes had turned so unexpectedly good early in 1860, they now turned unexpectedly bad. The deteriorating national situation made any business investment risky, and Thayer and Eldridge compounded the problem by making a number of bad business decisions. At the beginning of 1861, they declared bankruptcy and sold the plates of Leaves to Boston publisher Richard Worthington, who would continue to publish pirated copies of this edition for decades, creating real problems for Whitman every time he tried to market a new edition. Because of the large number of copies that Thayer and Eldridge initially printed, combined with Worthington's ongoing piracy, the 1860 edition became the most commonly available version of Leaves for the next twenty years and diluted the impact (as well as depressing the sales) of Whitman's new editions.Whitman had dated the title page of his 1860 Leaves "1860-61," as if he anticipated the liminal nature of that moment in American history—the fragile moment, between a year of peace and a year of war. In February 1861 he saw Abraham Lincoln pass through New York on the way to his inauguration, and in April he was walking home from an opera performance when he bought a newspaper and read the headlines about Southern forces firing on Fort Sumter. He remembers a group gathering in the New York streets that night as those with newspapers read the story aloud to the others in the crowd. Even though no one was aware of the full extent of what was to come—Whitman, like many others, thought the struggle would be over in sixty days or so—the nation was in fact slipping into four years of the bloodiest fighting it would ever know. A few days after the firing on Fort Sumter, Whitman recorded in his journal his resolution "to inaugurate for myself a pure perfect sweet, cleanblooded robust body by ignoring all drinks but water and pure milk—and all fat meats late suppers—a great body—a purged, cleansed, spiritualised invigorated body." It was as if he sensed at some level the need to break out of his newfound complacency, to cease his Pfaff's beerhall habits and bohemian ways, and to prepare himself for the challenges that now faced the divided nation. But it would take Whitman some time before he was able to discern the form his war sacrifice would take.

Whitman's brother George immediately enlisted in the Union Army and would serve for the duration of the war, fighting in many of the major battles; he eventually was incarcerated as a prisoner-of-war in Danville, Virginia. George had a distinguished career as a soldier and left the service as a lieutenant colonel; his descriptions of his war experiences provided Walt with many of his insights into the nature of the war and of soldiers' feelings. Whitman's chronically ill brother Andrew would also enlist but would serve only three months in 1862 before dying, probably of tuberculosis, in 1863. Walt's other brothers—the hot-tempered Jesse (whom Whitman had to have committed to an insane asylum in 1864 after he physically attacked his mother), the recently-married Jeff (on whom fell the burden of caring for the extended family, including his own infant daughter), and the mentally-enfeebled Eddy—did not enlist, and neither did Walt, who was already in his early forties when the war began.

One of the haziest periods of Whitman's life, in fact, is the first year and a half of the war. He stayed in New York and Brooklyn, writing some extended newspaper pieces about the history of Brooklyn for the Brooklyn Daily Standard; these pieces, called "Brooklyniana" and consisting of twenty-five lengthy installments, form a book-length anecdotal history of the city Whitman knew so well but was now about to leave—he would return only occasionally for brief visits. It was during this period that Whitman first encountered casualties of the war that was already lasting far longer than anyone had anticipated. He began visiting wounded soldiers who were moved to New York hospitals, and he wrote about them in a series called "City Photographs" that he published in the New York Leader in 1862.