Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

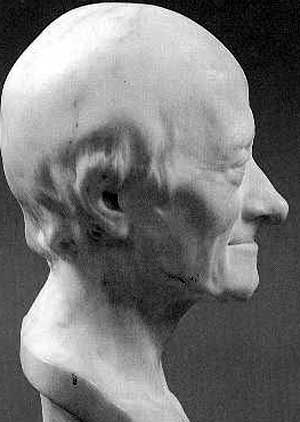

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

A company of tyrants is inaccessible to all seductions.

A witty saying proves nothing.

(Gemini Ascendant. Mercury in Sagittarius conjunct Descendant)All men are born with a nose and ten fingers, but no one was born with a knowledge of God.

All styles are good except the tiresome kind.

All the reasonings of men are not worth one sentiment of women.

An ideal form of government is democracy tempered with assassination.

Anyone who has the power to make you believe absurdities has the power to make you commit injustices.

Anything that is too stupid to be spoken is sung.

Appreciation is a wonderful thing: It makes what is excellent in others belong to us as well.

Behind every successful man stands a surprised mother-in-law.

Better is the enemy of good.

Business is the salt of life.

But nothing is more estimable than a physician who, having studied nature from his youth, knows the properties of the human body, the diseases which assail it, the remedies which will benefit it, exercises his art with caution, and pays equal attention to the rich and the poor.

By appreciation, we make excellence in others our own property.

Chance is a word void of sense; nothing can exist without a cause.

Clever tyrants are never punished.

Common sense is not so common.

Do well and you will have no need for ancestors.

Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is absurd.

Every man is guilty of all the good he did not do.

Every one goes astray, but the least imprudent are they who repent the soonest.

Everything is for the best in this best of possible worlds.

Everything's fine today, that is our illusion.

Fear follows crime and is its punishment.

For take thy balance if thou be so wise And weigh the wind that under heaven doth blow; Or weigh the light that in the east doth rise; Or weigh the thought that from man's mind doth flow.

Friendship is the marriage of the soul, and this marriage is liable to divorce.

Froth at the top, dregs at bottom, but the middle excellent.

God gave us the gift of life; it is up to us to give ourselves the gift of living well.

God is a comedian, playing to an audience too afraid to laugh.

He is a hard man who is only just, and a sad one who is only wise.

He must be very ignorant for he answers every question he is asked.

He shines in the second rank, who is eclipsed in the first.

He who has not the spirit of this age, has all the misery of it.

He who thinks himself wise, O heavens! is a great fool.

History is only the register of crimes and misfortunes.

How inexpressible is the meanness of being a hypocrite! How horrible is it to be a mischievous and malignant hypocrite.

How pleasant it is for a father to sit at his child's board. It is like an aged man reclining under the shadow of an oak which he has planted.

I am very fond of truth, but not at all of martyrdom.

(Scorpio Sun. Mercury & Mars in Sagittarius)I hate women because they always know where things are.

I know many books which have bored their readers, but I know of none which has done real evil.

(Gemini Ascendant)I Thy God am the Light and the Mind which were before substance was divided from Spirit and darkness from Light.

Ice-cream is exquisite - what a pity it isn't illegal.

If God created us in his own image, we have more than reciprocated.

If the bookseller happens to desire a privilege for his merchandise, whether he is selling Rabelais or the Fathers of the Church, the magistrate grants the privilege without answering for the contents of the book.

If we do not find anything pleasant, at least we shall find something new.

Illusion is the first of all pleasures.

In every author let us distinguish the man from his works.

Indeed, history is nothing more than a tableau of crimes and misfortunes.

Injustice in the end produces independence.

Is there anyone so wise as to learn by the experience of others?

It is an infantile superstition of the human spirit that virginity would be thought a virtue and not the barrier that separates ignorance from knowledge.

It is better to risk saving a guilty man than to condemn an innocent one.

It is dangerous to be right in matters on which the established authorities are wrong.

It is difficult to free fools from the chains they revere.

It is forbidden to kill; therefore all murderers are punished unless they kill in large numbers and to the sound of trumpets.

It is lamentable, that to be a good patriot one must become the enemy of the rest of mankind.

It is new fancy rather than taste which produces so many new fashions.

It is not enough to conquer; one must learn to seduce.

(Scorpio Sun. Venus in Scorpio.)It is not sufficient to see and to know the beauty of a work. We must feel and be affected by it.

It is said that the present is pregnant with the future.

It is the flash which appears, the thunderbolt will follow.

It is today, my dear, that I take a perilous leap.

It is vain for the coward to flee; death follows close behind; it is only by defying it that the brave escape.

Judge a man by his questions rather than by his answers.

Let us read and let us dance - two amusements that will never do any harm to the world.

Life is thickly sown with thorns, and I know no other remedy than to pass quickly through them. The longer we dwell on our misfortunes, the greater is their power to harm us.

Love has features which pierce all hearts, he wears a bandage which conceals the faults of those beloved. He has wings, he comes quickly and flies away the same.

Love is a canvas furnished by nature and embroidered by imagination.

Man is free at the moment he wishes to be.

(Uranus conjunct Ascendant)Meditation is the dissolution of thoughts in Eternal awareness or Pure consciousness without objectification, knowing without thinking, merging finitude in infinity.

(Neptune in Pisces)Men use thought only as authority for their injustice, and employ speech only to conceal their thoughts.

My life is a struggle.

Nature has always had more force than education.

Never argue at the dinner table, for the one who is not hungry always gets the best of the argument.

No problem can withstand the assault of sustained thinking.

No snowflake in an avalanche ever feels responsible.

Nothing can be more contrary to religion and the clergy than reason and common sense.

Nothing would be more tiresome than eating and drinking if God had not made them a pleasure as well as a necessity.

Now, now my good man, this is no time for making enemies.

One merit of poetry few persons will deny: it says more and in fewer words than prose.

Opinion has caused more trouble on this little earth than plagues or earthquakes.

Originality is nothing by judicious imitation. The most original writers borrowed one from another.

Our country is that spot to which our heart is bound.

Paradise was made for tender hearts; hell, for loveless hearts.

Perfection is attained by slow degrees; it requires the hand of time.

Prejudice, friend, governs the vulgar crowd.

Prejudices are what fools use for reason.

Satire lies about literary men while they live and eulogy lies about them when they die.

Self-love is the instrument of our preservation.

Slavery is also as ancient as war, and was as human nature.

Stand upright, speak thy thoughts, declare The truth thou hast, that all may share; Be bold, proclaim it everywhere: They only live who dare.

(Mercury in Sagittarius conjunct Descendant)Tears are the silent language of grief.

The ancient Romans built their greatest masterpieces of architecture, their amphitheaters, for wild beasts to fight in.

The ancients recommended us to sacrifice to the Graces, but Milton sacrificed to the Devil.

The art of government is to make two-thirds of a nation pay all it possibly can pay for the benefit of the other third.

The art of medicine consists in amusing the patient while nature cures the disease.

The best way to be boring is to leave nothing out.

The ear is the avenue to the heart.

The first step, my son, which one makes in the world, is the one on which depends the rest of our days.

The flowery style is not unsuitable to public speeches or addresses, which amount only to compliment. The lighter beauties are in their place when there is nothing more solid to say; but the flowery style ought to be banished from a pleading, a sermon, or a didactic work.

The infinitely little have a pride infinitely great.

The instruction we find in books is like fire. We fetch it from our neighbours, kindle it at home, communicate it to others, and it becomes the property of all.

The little may contrast with the great, in painting, but cannot be said to be contrary to it. Oppositions of colors contrast; but there are also colors contrary to each other, that is, which produce an ill effect because they shock the eye when brought very near it.

The mouth obeys poorly when the heart murmurs.

The multitude of books is making us ignorant.

The opportunity for doing mischief is found a hundred times a day, and of doing good once in a year.

The progress of rivers to the ocean is not so rapid as that of man to error.

The public is a ferocious beast; one must either chain it or flee from it.

The safest course is to do nothing against one's conscience. With this secret, we can enjoy life and have no fear from death.

The sovereign is called a tyrant who knows no laws but his caprice.

The very impossibility in which I find myself to prove that God is not, discovers to me his existence.

The world embarrasses me, and I cannot dream that this watch exists and has no watchmaker.

(Uranus conjunct Ascendant)There are truths which are not for all men, nor for all times.

Think for yourselves and let others enjoy the privilege to do so, too.

This self-love is the instrument of our preservation; it resembles the provision for the perpetuity of mankind: it is necessary, it is dear to us, it gives us pleasure, and we must conceal it.

To be at peace in crime! ah, who can thus flatter himself.

To believe in God is impossible, not to believe in Him is absurd.

To hold a pen is to be at war.

To succeed in the world it is not enough to be stupid, you must also be well-mannered.

To the wicked, everything serves as pretext.

Tyrants have always some slight shade of virtue; they support the laws before destroying them.

Use, do not abuse; neither abstinence nor excess ever renders man happy.

Very learned women are to be found, in the same manner as female warriors; but they are seldom or ever inventors.

Very often, say what you will, a knave is only a fool.

We are all full of weakness and errors; let us mutually pardon each other our follies - it is the first law of nature.

We are rarely proud when we are alone.

We cannot always oblige; but we can always speak obligingly.

We cannot wish for that we know not.

We have a natural right to make use of our pens as of our tongue, at our peril, risk and hazard.

We must distinguish between speaking to deceive and being silent to be reserved.

Weakness on both sides is, as we know, the motto of all quarrels.

What a heavy burden is a name that has become too famous.

What is tolerance? It is the consequence of humanity. We are all formed of frailty and error; let us pardon reciprocally each other's folly - that is the first law of nature.

What most persons consider as virtue, after the age of 40 is simply a loss of energy.

What then do you call your soul? What idea have you of it? You cannot of yourselves, without revelation, admit the existence within you of anything but a power unknown to you of feeling and thinking.

When he to whom one speaks does not understand, and he who speaks himself does not understand, that is metaphysics.

When it is a question of money, everybody is of the same religion.

Whoever serves his country well has no need of ancestors.

You see many stars at night in the sky but find them not when the sun rises; can you say that there are no stars in the heaven of day? So, O man! because you behold not God in the days of your ignorance, say not that there is no God.

Your destiny is that of a man, and your vows those of a god.

Born 21 November 1694

Paris, France

Died 30 May 1778 (age 83)

Paris, France

Occupation Writer and philosopher

Parents François Arouet, father; Marie Marguerite d’Aumart, mother

François-Marie Arouet (21 November 1694 – 30 May 1778), better known by the pen name Voltaire, was a French Enlightenment writer, essayist, deist and philosopher known for his wit, philosophical sport, and defense of civil liberties, including freedom of religion and the right to a fair trial. He was an outspoken supporter of social reform despite strict censorship laws in France and harsh penalties for those who broke them. A satirical polemicist, he frequently made use of his works to criticize Christian Church dogma and the French institutions of his day.Early years

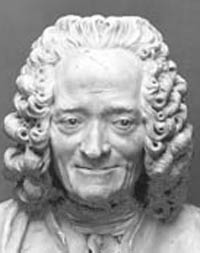

Bust of Voltaire by the artist Antoine Houdon, 1781.François-Marie Arouet de Voltaire was born in Paris in 1694, the last of the five children of François Arouet (1650–1 January 1722) a notary who was a minor treasury official, and his wife, Marie Marguerite d'Aumart (c.1660–13 July 1701) from a noble family from the Poitou province. Voltaire was educated by Jesuits at the Collège Louis-le-Grand (1704-11), where he learned Latin and Greek; later in life he became fluent in Italian, Spanish and English. From 1711 to 1713 he studied law. Before devoting himself entirely to writing, Voltaire worked as a secretary to the French ambassador in Holland, where he fell in love with a French refugee, named Catherine Olympe Dunoyer. Their elopement was foiled by Voltaire's father, and he was forced to return to France. Most of Voltaire's early life revolved around Paris until his exile. From the beginning Voltaire had trouble with the authorities for his energetic attacks on the government and the Catholic Church. These activities were to result in numerous imprisonments and exiles. In his early twenties he spent eleven months in the Bastille for writing satirical verses about the aristocracy.After graduating, Voltaire set out on a career in literature. His father, however, intended his son to be educated in the law. Voltaire, pretending to work in Paris as an assistant to a lawyer, spent much of his time writing satirical poetry. When his father found him out, he again sent Voltaire to study law, this time in the provinces. Nevertheless, he continued to write, producing essays and historical studies not always noted for their accuracy. Voltaire's wit made him popular among some of the aristocratic families. One of his writings, about Louis XV's regent, Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, led to his being imprisoned in the Bastille. While there, he wrote his debut play, Œdipe, and adopted the name Voltaire which came from his hometown in southern France . Œdipe's success began Voltaire's influence and brought him into the French Enlightenment.

The Château de Cirey

at 70 years old, an engraving from an 1843 edition of his Philosophical DictionaryVoltaire then set out to the Château de Cirey, located on the borders of Champagne, France and Lorraine. The building was renovated with his money, and here he began a relationship with the Marquise du Châtelet, Gabrielle Émilie le Tonnelier de Breteuil. The Chateau de Cirey was owned by the Marquise's husband, Marquis Florent-Claude du Chatelet, who sometimes visited his wife and her lover at the chateau. Their relationship, which lasted for fifteen years, led to much intellectual development. Voltaire and the Marquise collected over 21,000 books, an enormous number for their time. Together, Voltaire and the Marquise also studied these books and performed experiments. Both worked on experimenting with the "natural sciences," the term used in that epoch for physics, in his laboratory. Voltaire performed many experiments including one that attempted to determine the properties of fire.The 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica comments that "If the English visit may be regarded as having finished Voltaire's education, the Cirey residence was the first stage of his literary manhood." Having learned from his previous brushes with the authorities, Voltaire began his future habit of keeping out of personal harm's way, and denying any awkward responsibility. He continued to write, publishing plays such as Mérope and some short stories. Again, a main source of inspiration for Voltaire were the years he spent exiled in England. During his time there, Voltaire had been strongly influenced by the works of Sir Isaac Newton, a leading philosopher and scientist of the epoch. Voltaire strongly believed in Newton's theories, especially concerning optics (Newton’s discovery that white light is composed of all the colors in the spectrum led to many experiments by him and the Marquise), and gravity (the story of Newton and the apple falling from the tree is mentioned in his Essai sur la poésie épique, or Essay on Epic Poetry). Although both Voltaire and the Marquise were also curious about the philosophies of Gottfried Leibniz, a contemporary and rival of Newton, the pair remained "Newtonians" and based their theories on Newton’s works and ideas. Though it has been stated that the Marquise may have been more "Leibnizian", which may have caused tension between the two, this is probably an exaggeration; the Marquise even wrote "je newtonise," which, translated, means "I am 'newtoning'". Voltaire wrote a book on Newton's philosophies: the Eléments de la philosophie de Newton (The Elements of Newton's Philosophies). The Elements was probably written with the Marquise, and describes the other branches of Newton's ideas that fascinated him: it spoke of optics and the theory of attraction (gravity).

Voltaire and the Marquise also studied history - particularly the people who had contributed to civilization up to that point. Voltaire had worked with history since his time in England; his second essay in English had the title Essay upon the Civil Wars in France. When he returned to France, he wrote a biographical essay of King Charles XII. This essay was the beginning of Voltaire's rejection of religion; he wrote that human life is not destined or controlled by greater beings. The essay won him the position of historian in the king's court. Voltaire and the Marquise also worked with philosophy, particularly with metaphysics, the branch of philosophy dealing with the distant, and what cannot be directly proven: why and what life is, whether or not there is a God, and so on. Voltaire and the Marquise analyzed the Bible, trying to find its validity in the world. Voltaire renounced religion; he believed in the separation of church and state and in religious freedom, ideas he formed after his stay in England. Voltaire even claimed that "One hundred years from my day there will not be a Bible in the earth except one that is looked upon by an antiquarian curiosity seeker."

Die Tafelrunde by Adolph von Menzel. Guests of Frederick the Great, in Marble Hall at Sanssouci, include members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences and Voltaire (seated, third from left).After the death of the Marquise, Voltaire moved to Berlin to join Frederick the Great, a close friend and admirer of his. The king had repeatedly invited him to his palace, and now gave him a salary of 20,000 francs a year. Though life went well at first, he began to encounter difficulties. Faced with a lawsuit and an argument with the president of the Berlin Academy of Science, Voltaire wrote the Diatribe du Docteur Akakia (Diatribe of Doctor Akakia) which derided the president. This greatly angered Frederick, who had all copies of the document burned and arrested Voltaire at an inn where he was staying along his journey home. Voltaire headed toward Paris, but Louis XV banned him from the city, so instead he turned to Geneva, where he bought a large estate. Though he was received openly at first, the law in Geneva which banned theatrical performances and the publication of La pucelle d'Orléans against his will led to Voltaire's writing of Candide, ou l'Optimisme (Candide, or Optimism) in 1759 and his eventual departure. Candide, a satire on the philosophy of Leibniz, remains the work for which Voltaire is perhaps best known.

From an early age, Voltaire displayed a talent for writing verse, and his first published work was poetry. He wrote two long poems, the Henriade, and the Pucelle, besides many other smaller pieces.

The Henriade was written in imitation of Virgil, using the Alexandrine couplet reformed and rendered monotonous for dramatic purposes. Voltaire lacked both enthusiasm for and understanding of the subject, which both negatively impacted the poem's quality. The Pucelle, on the other hand, is a burlesque work attacking religion and history. Voltaire's minor poems are generally considered superior to either of these two works.

Prose and romances

Many of Voltaire's prose works and romances, usually composed as pamphlets, were written as polemics. Candide attacks religious and philosophical optimism, L'Homme aux quarante ecus certain social and political ways of the time, Zadig and others the received forms of moral and metaphysical orthodoxy, and some were written to deride the Bible. In these works, Voltaire's ironic style without exaggeration is apparent, particularly the extreme restraint and simplicity of the verbal treatment. Voltaire never dwells too long on a point, stays to laugh at what he has said, elucidates or comments on his own jokes, guffaws over them or exaggerates their form. Candide in particular is the best example of his style.Voltaire also has, in common with Jonathan Swift, the distinction of paving the way for science fiction's philosophical irony, particularly in his Micromegas.

Voltaire's Deism, like many key figures of the European Enlightenment, was a Deist. He did not believe that faith was needed to believe in God. He wrote, "What is faith? Is it to believe that which is evident? No. It is perfectly evident to my mind that there exists a necessary, eternal, supreme, and intelligent being. This is no matter of faith, but of reason." [1]

Rejecting Christianity, Voltaire apparently believed in God based solely on reason, and without supplementation or foundation in any particular religious book or tradition of revelation.

Views on Christianityopposed Christian beliefs fiercely. He argued that the Gospels were fabricated and Jesus did not exist - that they were produced by those who wanted to create God in their own image and were full of discrepancies. On the other hand, he quoted the Scripture extensively and expertly in such works as Traité sur la Tolérance to argue in favor of tolerance for "fanatic" religious minorities, in that case the Protestants. Neither did he hide his sympathy for the Jansenists.

Voltaire is reputed to have proclaimed about the Bible, "In 100 years this book will be forgotten and eliminated...", although there is no direct evidence that he made such a statement. In his later years (1759) Voltaire purchased an estate called "Ferney" on the French-Swiss border. As the property straddled the border, Voltaire joked that when the French Catholics were against him, he lived on the Swiss (Protestant) half, and vice versa. There is an apocryphal story that this house was purchased by the Geneva Bible Society and used for printing Bibles, but this appears to be due to a misunderstanding of the 1849 annual report of the American Bible Society [2]. Voltaire's chateau is now owned and administered by the French Ministry of Culture.

Views on raceexpressed his views on race, mostly in his work Essai sur les mœurs, holding that black people, whom he called "animals", were a peculiar species of human because of what he perceived as great differences from other humans, both physically and mentally. Voltaire expressed much the same views in his personal correspondence. In Traité de Métaphysique, his philosophical narrator claimed that white men "seem to be superior to Negroes, just as Negroes are superior to monkeys and monkeys to oysters." Voltaire's stance on blacks may be related to his financial interests. The philosopher made an investment in a slave-trading enterprise in Nantes, which, according to the contemporaneous observers, made him one of the twenty richest men in France.[citation needed] However, some passages of Candide reveal hostility to the violent treatment of slaves,[1] although in Essai sur les moeurs he states that Negroes are born to be slaves.[2]

Views on Jews's viewpoint on Jews, Judaism and all organized religion reveals antisemitism on his part. He once wrote, "The Jewish nation dares to display an irreconcilable hatred toward all nations, and revolts against all masters; always superstitious, always greedy for the well-being enjoyed by others, always barbarous — cringing in misfortune and insolent in prosperity."

Philosophy's largest philosophical work is the Dictionnaire philosophique, comprising articles contributed by him to the Encyclopédie and of several minor pieces. It directed criticism against French political institutions, Voltaire's personal enemies, the Bible and the Roman Catholic Church, showing the character, literary and personal, of Voltaire.

Views on New Francewas a critic of France's colonial policy in North America, dismissing the vast territory of New France as "a few acres of snow" ("quelques arpents de neige") that produced little more than furs and required constant - and expensive - military protection from the mother country against Great Britain's 13 Colonies to the south.[citation needed]

Correspondencealso engaged in an enormous amount of private correspondence during his life, totalling over 21,000 letters. His personality shows through in the letters that he wrote: his energy and versatility, his unhesitating flattery when he chose to flatter, his ruthless sarcasm, his unscrupulous business faculty and his resolve to double and twist in any fashion so as to escape his enemies.

Miscellaneous

In general criticism and miscellaneous writing, Voltaire's writing was comparable with that in his other works. Almost all his more substantive works, whether in verse or prose, are preceded by prefaces of one sort or another, which are models of his caustic yet conversational tone. In a vast variety of nondescript pamphlets and writings, he displays his skills at journalism. In pure literary criticism his principal work is the Commentaire sur Corneille, although he wrote many more similar works — sometimes (as in his Life and notices of Molière) independently and sometimes as part of his Siécles.Voltaire's works, especially his private letters, constantly contain the word "l'infâme" and the expression (in full or abbreviated) "écrasez l'infâme." This expression has sometimes been misunderstood as meaning Christ, but the real meaning is "crush the infamy (infamous)". Particularly, it is the system which Voltaire saw around him, the effects of which he had felt in his own exiles and the confiscations of his books, and which he had seen in the hideous sufferings of Calas and La Barre.

Legacy

's statue and tomb in the crypt of the Panthéon.Voltaire perceived the French bourgeoisie to be too small and ineffective, the aristocracy to be parasitic and corrupt, the commoners as ignorant and superstitious, and the church as a static force useful only as a counterbalance since its "religious tax" or the tithe helped to create a strong backing for revolutionaries.Voltaire distrusted democracy, which he saw as propagating the idiocy of the masses. To Voltaire, only an enlightened monarch or an enlightened absolutist, advised by philosophers like himself, could bring about change as it was in the king's rational interest to improve the power and wealth of his subjects and kingdom. Voltaire essentially believed monarchy to be the key to progress and change.

He supported "bringing order" through military means in his letters to Catherine II of Russia and Frederick II of Prussia where he strongly praised the Partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. He was, however, deeply opposed to the use of war and violence as means for the resolution of controversies, as he repeatedly and forcefully stated in many of his works, including the "Philosophical Dictionary," where he described war as a "hellish enterprise" and those who resort to it "ridiculous murderers."

He is best known today for his novel, Candide, ou l'Optimisme (Candide, or Optimism, 1759), which satirized the philosophy of Leibniz. Candide was also subject to censorship and Voltaire jokingly claimed that the actual author was a certain "Dr DeMad" in a letter, where he reaffirmed the main polemical stances of the text. [3]

Voltaire is also known for many memorable aphorisms, such as: "Si Dieu n'existait pas, il faudrait l'inventer" ("If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him"), contained in a verse epistle from 1768, addressed to the anonymous author of a controversial work, The Three Impostors.

Jean-Baptiste Rousseau, not to be confused with the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, sent a copy of his "Ode to Posterity" to Voltaire. Voltaire read it through and said, "I do not think this poem will reach its destination."[citation needed]

Voltaire is remembered and honored in France as a courageous polemicist who indefatigably fought for civil rights — the right to a fair trial and freedom of religion — and who denounced the hypocrisies and injustices of the ancien régime. The ancien régime involved an unfair balance of power and taxes between the First Estate (the clergy), the Second Estate (the nobles), and everyone else (the commoners and middle class, who were burdened with most of the taxes).

Thomas Carlyle argued that while he was unsurpassed in literary form, not even the most elaborate of Voltaire's works was of much value for matter and that he never uttered an original idea of his own.

Voltaire did not let his ideals interfere with the acquisition of his fortune. He was a millionaire by the time he was forty after cultivating the friendship of the Paris brothers who had a contract to supply the French army with food and munitions and being invited to participate with them in this extremely profitable enterprise. According to a review in the March 7, 2005 issue of The New Yorker of Voltaire's Garden, a mathematician friend of his realized in 1728 that the French government had authorized a lottery in which the prize was much greater than the collective cost of the tickets. He and Voltaire formed a syndicate, collected all the money, and became moneylenders to the great houses of Europe. Voltaire complained that lotteries exploited the poor.

The town of Ferney, France, where Voltaire lived out the last 20 years of his life (though he died in Paris), is now named Ferney-Voltaire. His château is now a museum (L'Auberge de l'Europe). Voltaire's library is preserved intact in the Russian National Library, St Petersburg. His remains were interred at the Panthéon, in Paris, in 1791.

The pen name "Voltaire"

The name "Voltaire," which he adopted in 1718 not only as a pen name but also in daily use, is an anagram of the Latinized spelling of his surname "Arovet" and the letters of the sobriquet "le jeune" ("the younger"): AROVET Le Ieune. The name also echoes in reversed order the syllables of a familial château in the Poitou region: "Airvault". The adoption of this name after his incarceration at the Bastille is seen by many to mark a formal separation on the part of Voltaire from his family and his past.Richard Holmes in "Voltaire's Grin" also believes that the name "Voltaire" arose from the transposition of letters. But he adds that a writer such as Voltaire would have intended the name to carry its connotations of speed and daring. These come from associated words such as: "voltige" (acrobatics on a trapeze or horse), "volte-face" (spinning about to face your enemies), and "volatile" (originally any winged creature).

Voltaire

an outline biographyFrançois Marie Arouet (who later assumed the name Voltaire) was born in Paris on November 21st 1694. The family was wealthy, his father was a notary and his mother maintained contacts with friends interested in belles-lettres and Deism.

From 1704 - 1711 François Marie was educated by the Jesuits at the College Louis-le-Grand, his later involvement with the writing and staging of plays may have been encouraged by the numerous plays, in Latin as well as French, that were staged at College Louis-le-Grand.

Despite his father's wishes that he train for a career in Law François Marie, after a short period of work in a legal office, chose to attempt to pursue a literary career. He soon began to fall in with questionable company and to cause offense through the power and sarcasm of his wit and poetry. Because of these tendencies his father, on several occasions, arranged for him to spend time away from Paris.

From about 1715 François Marie increasingly began moving in aristocratic circles including a famous salon-court that was maintained by the Duchesse du Maine at Sceaux. He became recognised in Paris as a brilliant and sarcastic wit - a lampoon of the French regent the Duc d'Orléans and also his being accused, (unjustly), of penning two distinctly libelous poems resulted in his imprisonment in the Bastille. This imprisonment being imposed following the composition of a lettre de cachet, an administrative order, issued at the request of powerful persons. François Marie was most aggrieved at this unjust sentence to imprisonment being imposed on him.

It was during his subsequent eleven month period of detention that François Marie Arouet / Voltaire completed his first dramatic tragedy, Oedipe. This dramatic work was based upon the play Oedipus Tyrannus attributable to the ancient Greek dramatist Sophocles. (It was during these times that François Marie adopted the pen name Voltaire). Voltaire's Oedipe opened at the Théâtre Français in 1718 and received an enthusiastic response.

During his period of detention in the Bastille he had also begun to craft a poem centered on the life of Henry IV of France. An early edition of this work, which features an eloquent appeal for religious toleration, was printed anonymously in Geneva under the title of Poème de la ligue (Poem of the League, 1723). King Henry IV had been an Huguenot (protestant) claimant to the French throne but was only accepted as King after modifying his approach to religion.

Voltaire was consigned to the Bastille, again by lettre de cachet, after he had given offence to the chevalier de Rohan who was member of one of the most powerful families in France. This time however he was released within two weeks following his promise to actually quit France and to begin a period of exile. Accordingly he spent almost three years in London where he soon mastered the English language and wrote, in English, two remarkable works, an "Essay upon Epic Poetry" and an "Essay upon the Civil Wars in France". Whilst in England he regularly attended the theatres and playhouses and saw several performances of Shakespeare's plays.

During his exile in London he made a serious study of the new philosophical ideas of John Locke that questioned both the Divine Right of Kings and also the Authority of the State. He was also impressed by the English Constitutional arrangements:-

"We can well believe that a constitution that has established the rights of the Crown, the aristocracy and the people, in which each section finds its own safety, will last as long as human institutions can last".

The scientific discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton also attracted his serious attention. For the rest of his long literary and philosophical career he did a very great deal to popularise the ideas of Locke and to spread knowledge of the discoveries of Newton. It can be suggested that Locke's and Newton's ideas tended to encourage people to have faith in their own physical senses and in their powers of reason to the detriment, more often than not, of religious faith.In 1728 the autocratic French government finally allowed the Poème de la ligue, (which was now retitled La Henriade) to be published in France. This work achieved a most remarkable acclaim, not only in France but throughout all of the continent of Europe as well.

Voltaire returned to France in 1728 and was to reside in Paris over the subsequent four years devoting his time to literary activities. The chief work of this period is the Lettres anglaises ou philosophiques (English or Philosophical Letters, 1734). This work favourably commented upon the relative ease with which educated commoners in England might take up occupations and professions, it also strongly suggested that there was a degree of press freedom, of equality of taxation, and of respect shown to the individual, and to the law, in England that should be emulated elsewhere. His Lettres anglaises ou philosophiques effectively constituted a covert attack upon the political and ecclesiastical institutions of France and thus brought him into conflict with the authorities.

Voltaire was once more forced to quit Paris and found refuge from the French authorities at the Château de Cirey in Lorraine, then an independent Duchy. There he formed an intimate relationship with the learned Marquise du Châtelet, who exerted a strong intellectual influence upon him. In 1735 he was given leave to return to Paris by the French authorities but, in the event, he preferred to continue as he was at Cirey. He did however make visits to Paris, Versailles, and elsewhere.

Several years thereafter and largely through the influence of the Marquise de Pompadour, the famous mistress of Louis XV, Voltaire became a court favorite. He was appointed Royal Historiographer of France, and then a gentleman of the King's bedchamber. In 1746 he was elected to the French Academy.Following the death of Madame du Châtelet in 1749, he finally accepted a long-standing invitation from Frederick II of Prussia to become resident at the Prussian court. He journeyed to Berlin in 1750 but did not remain there more than two years due to a series of misunderstandings and scandals. There was at this time something of a fashion for European rulers to style themselves as being enlightened despots. Apart from Frederick II, King of Prussia, Catherine the Empress of the Russias is perhaps the most notable example of this. The Empress used also, in fact, to correspond with him.

Following his departure from Berlin he was not welcome to return to France and began a series of temporary stays in towns, such as Colmar and Geneva, along her frontiers. During these years he completed his most ambitious work, the Essay on General History and on the Customs and the Character of Nations, 1756. This work sets itself out to be a study of human progress, through its pages he denounced the power of the clergy but made evident his own rationalist-deist belief in the existence of God. From 1758 he established a more enduring home at Ferney, nearby to Geneva but within the frontiers of the French kingdom, where he spent the remaining 20 years of his life. Many European celebrities subsequently included a visit to Ferney in their itineraries - a fact which tended to establish Ferney as the virtual intellectual capital of Europe.

Voltaire is considered to have been a central figure in the emergence of the Enlightenment movement in Europe where people were increasingly encouraged to practice toleration in religion and to look to the practical application of natural laws discovered by science for the material improvement of human life. He also tended to effectively persuade people that superstition was ridiculous.

After settling in Ferney, he wrote several philosophical poems, such as Le désastre de Lisbonne (The Lisbon Disaster, 1756), and a number of satirical and philosophical novels, of which the most brilliant is Candide (1759).

The publication of the Dictionnaire philosophique (1764) met with condemnation in Paris and other European cities. It was considered to encourage people to look to reason rather than to faith. A copy of the Dictionnaire philosophique was actually burned at the same time as the unfortunate young Chevalier de la Barre, who had neglected to take of his hat, and kneel, during the passing of a religious procession. Given the furore over the Dictionnaire he thought it prudent to deny authorship and to seek exile for a few weeks in Switzerland.

Voltaire contributed to what proved to be perhaps the greatest intellectual project of the times, the great ongoing Encyclopedié edited by the Philosophés Denis Diderot and Jean d'Alembert. The Encyclopedié was also to become the subject of controversy as it too was considered to challenge faith by encouraging people to look to the power of reason.

Voltaire considered that his own earlier life experiences of imprisonment and exile for exercising his wit at the expense of the powerful were effectively a result of the abuse of power. Individuals should not have to live under the threat of such abuse by the powerful in society. From Ferney his mind and pen sent forth hundreds of literary utterances in defence of freedom of thought and of religious tolerance. He was also very apt to satirise and to expose what he considered to be abuses. Those who seemed to have suffered persecution because of their beliefs found in him an eloquent and influential defender.

His championship of freedom of thought and of religious tolerance in several notable cases brought him into a direct conflict with the Catholic church authorities. He saw the Catholic church authorities in France as often behaving in a repressive manner and particularly so towards Huguenots. He often used the phrase écrasons l'infâme let us crush the infamous one by which he seems to have meant intellectual, religious, and social intolerance generally.

In 1778 Voltaire was given a rapturous welcome on his return to Paris and died there, in his sleep on May 30th, possibly over-excited by his recent journey and welcome. Because of his many unorthodoxies he was refused burial in church ground but eventually found a resting place in the grounds of the Abbey of Sellières, near Romilly-sur-Seine.

From 1789 there was a revolution in France which, amongst many other things, unmistakeably upheld "reason" and "virtue". In relation to Voltaire some of the leading revolutionaries considered that the "glorious Revolution has been the fruit of his works". In July 1791 his remains were dis-interred and, amidst great ceremony, re-housed in an imposing Sarcophagus in the Panthéon in Paris. The Panthéon being a recently completed building that had been begun as a church of St. Genevieve but which had been finished, by the revolutionary government, as a monument to those designated by the revolutionaries as "les Grands Hommes." As Voltaire's remains were borne toward the Panthéon, in a hearse designed by the painter David that bore the inscription "He taught us to be free", they were escorted by the National Guard. Perhaps an hundred thousand people followed in the cortege with many more thousands looking on.

At this time Voltaire shared the Panthéon with René Descartes, regarded by the intellectual heirs of the Enlightenment as the patron saint of Reason, and also the revolutionary leader Mirabeau.

In 1814, with the French revolutionary and Napoleonic era being ended by a restoration of the Bourbon monarchy a group of persons who tended to hold right-wing, clericalist, political views clandestinely removed his remains from the Panthéon - although their absence was not discovered until 1864.

Voltaire's heart and brain, however, had been removed even before the burial in Champagne - his brain is today preserved in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris - his heart was in the care of a series of private custodianships for more than one hundred years but eventually disappeared after an auction.