Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

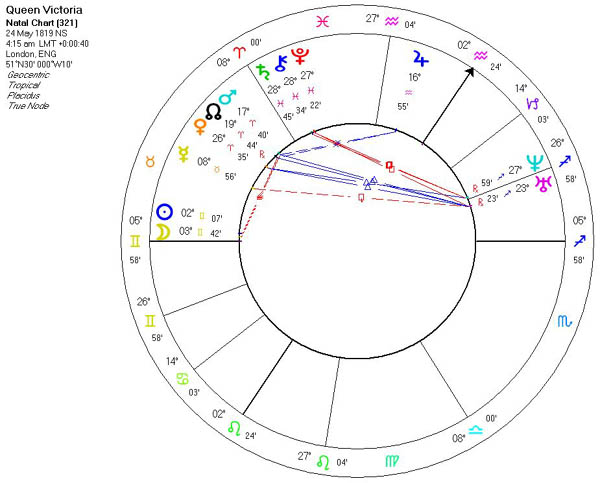

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

Being pregnant is an occupational hazard of being a wife.

Everybody grows but me.

I feel sure that no girl would go to the altar if she knew all.

I would venture to warn against too great intimacy with artists as it is very seductive and a little dangerous.

The important thing is not what they think of me, but what I think of them.

The Queen is most anxious to enlist everyone in checking this mad, wicked folly of 'Women's Rights'. It is a subject which makes the Queen so furious that she cannot contain herself.

We are not interested in the possibilities of defeat. They do not exist.

(Mars in Aries conjunct North Node. Jupiter in 10th house.)The Queen is most anxious to enlist everyone who can speak or write to join in checking this mad, wicked folly of “Woman’s Rights” with all its attendant horrors on which her poor, feeble sex is bent, forgetting every sense of womanly feeling and propriety.

O! if those selfish men—who are the cause of all one’s misery, only knew what their poor slaves go through! What suffering—what humiliation to the delicate feelings of a poor woman, above all a young one—especially with those nasty doctors.

For a man to strike any women is most brutal, and I, as well as everyone else, think this far worse than any attempt to shoot, which, wicked as it is, is at least more comprehensible and more courageous.

Victoria (1819–1901), British monarch, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland. in Her Letters and Journals, entry for July 2, 1850, ed. Christopher Hibbert (1984).

Victoria had survived two assassination attempts.His purity was too great, his aspiration too high for this poor, miserable world! His great soul is now only enjoying that for which it was worthy!

December 20, 1861, to Leopold I, King of Belgium. Letters of , vol. 3, ch. 30, eds. A.C. Benson and Viscount Esher (1907).

Victoria was referring to Albert, the Prince Consort.Men never think, at least seldom think, what a hard task it is for us women to go through this very often. God’s will be done, and if He decrees that we are to have a great number of children why we must try to bring them up as useful and exemplary members of society.

Jan. 5, 1841, to her uncle King Leopold of the Belgians, written after the birth of her first child. in Her Letters and Journals, ed. Christopher Hibbert (1984).

Leopold had expressed the hope that Princess Victoria would be the first of many children; Victoria eventually mothered nine.I don’t dislike babies, though I think very young ones rather disgusting.

May 8, 1872, to her daughter, the Crown Princess of Prussia. in Her Letters and Journals, ed. Christopher Hibbert (1984).We placed the wreaths upon the splended granite sarcophagus, and at its feet, and felt that only the earthly robe we loved so much was there. The pure, tender, loving spirit which loved us so tenderly, is above us—loving us, praying for us, and free from all suffering and woe—yes, that is a comfort, and that first birthday in another world must have been a far brighter one than any in this poor world below!

Victoria (1819–1901), British Queen of Great Britain and Ireland. Letter, August 20, 1861. Letters of , vol. 3, ch. 30, eds. A.C. Benson and Viscount Esher (1907).

Writing to to Leopold I, King of the Belgians, was speaking about the Duchess of Kent.I think people really marry far too much; it is such a lottery after all, and for a poor woman a very doubtful happiness.

May 3, 1858, to her daughter, Crown Princess Frederick William of Prussia. in Her Letters and Journals, ed. Christopher Hibbert (1984).I positively think that ladies who are always enceinte quite disgusting; it is more like a rabbit or guinea-pig than anything else and really it is not very nice.

June 15, 1859, to her daughter Louisa, Princess Frederick William of Prussia. in Her Letters and Journals, ed. Christopher Hibbert (1984).When I think of a merry, happy, free young girl—and look at the ailing, aching state a young wife generally is doomed to—which you can’t deny is the penalty of marriage.

May 16, 1860, to her daughter Princess Frederick William. in Her Letters and Journals, ed. Christopher Hibbert (1984).A marriage is no amusement but a solemn act, and generally a sad one.

The poor fatherless baby of eight months is now the utterly broken-hearted and crushed widow of forty-two! My life as a happy one is ended! the world is gone for me! If I must live on (and I will do nothing to make me worse than I am), it is henceforth for our poor fatherless children—for my unhappy country, which has lost all in losing him—and in only doing what I know and feel he would wish.

Dec. 20, 1861, to Leopold I, King of the Belgians. Letters of , vol. 3, ch. 30, eds. A.C. Benson and Viscount Esher (1907).

Said of the death of Albert, the Prince Consort. Victoria’s three-year seclusion and long mourning earned her the sobriquet of “the Widow of Windsor.”

(Pluto in Pisces square Uranus in 7th house.)I am every day more convinced that we women, if we are to be good women, feminine and amiable and domestic, are not fitted to reign; at least it is contre gré that they drive themselves to the work which it entails.

We women are not made for governing and if we are good women, we must dislike these masculine occupations; but there are times which force one to take interest in them mal gré bon gré, and I do, of course, intensely.

Feb. 3, 1852, to Leopold I, King of the Belgians. Letters of , vol. 2, ch. 21, eds. A.C. Benson and Viscount Esher (1907).

(Mars and Venus in Aries in conjunct North Node.)None of you can ever be proud enough of being the child of SUCH a Father who has not his equal in this world—so great, so good, so faultless. Try, all of you, to follow in his footsteps and don’t be discouraged, for to be really in everything like him none of you, I am sure, will ever be. Try, therefore, to be like him in some points, and you will have acquired a great deal.

Aug. 26, 1857, to the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII."Great events make me quiet and calm; it is only trifles that irritate my nerves."

It seems to me a defect in our much famed constitution, to have to part with an admirable government like Lord Salisbury's for no question of any importance, or any particular reason, merely on account of the number of votes.

We are not amused.

To a jester who did an impersonation of her."What you say of the pride of giving life to an immortal soul is very fine dear, but I own I cannot enter into that: I think much more of our being like a cow or a dog at such moments: when our poor nature becomes so very animal and unecstatic"

"Do not to let your feelings (very natural and usual ones) of momentary irritation and discomfort be seen by others; don't (as you so often did and do) let every little feeling be read in your face and seen in your manner . . ." May- 1837 (Reference to her birthday)

"Today is my eighteenth birthday! How old! and yet how far am I from being what I should be. I shall from this day take the firm resolution to study with renewed assiduity, to keep my attention always well fixed on whatever I am about, and to strive to become every day less trifling and more fit for what, if Heaven wills it, I'm some day to be.

The courtyard and the streets were crammed when we went to the Ball, and the anxiety of the people to see poor stupid me was very great, and I must say I am quite touched by it, and feel proud, which I always have done, of my country and of the English nation."June- 1837 (Reference to the coronation)

"I look forward to the event which it seems is likely to occur soon, with calmness and quietness. I am not alarmed at it, and yet I do not suppose myself quite equal to all; I trust, however, that with good-will, honesty, and courage I shall not, at all events, fail."

"The tremendous cheering, the joy expressed in every face, the vastness of the building, with all its decorations and exhibits, the sounds of the organ, and my beloved husband the creator of this great 'Peace Festival', uniting the industry and art of all nations of the earth was quite overwhelming."

"I am sick of all this horrid business - of politics and Europe in general, and think you (daughter Vicky) will hear some day of my going with the children to live in Australia, and to think of Europe as of the moon."

March- 1861 (Reference the death of her mother)"I knelt before her, kissed her dear hand and placed it next to my cheek. But though she opened her eyes she did not, I think, know me."

December- 1861 (Reference the death of Prince Albert)"Never can I forget how beautiful my darling looked lying there with his face lit up by the rising sun, his eyes unusually bright gazing as it were on unseen objects and not taking notice of me. I stood up, kissed his dear heavenly forehead and called out in a bitter agonizing cry: 'Oh! my dear darling!', and then dropped on my knees in mute, distracted despair unable to utter a word or shed a tear."

" I am most anxious to enlist everyone who can speak or write to join in checking this mad, wicked folly of 'Women's Rights', with all its attendant horrors, on which her poor feeble sex is bent, forgetting every sense of womanly feelings and propriety. Feminists ought to get a good whipping. Were woman to 'unsex' themselves by claiming equality with men, they would become the most hateful, heathen and disgusting of beings and would surely perish without male protection."

"I love peace and quiet, I hate politics and turmoil. We women are not made for governing, and if we are good women, we must dislike these masculine occupations. There are times which force one to take interest in them, and I do, of course intensely"

I regret exceedingly not to be a man and to be able to fight in the war. There is no finer death for a man than on the battlefield".

(Mars in Aries.)When Russia declared war against Turkey in 1877, wrote; "Oh, if the Queen were a man, she would like to go and give those horrid Russians such a beating."

Her Majesty (Alexandrina Victoria von Wettin, née d'Este)) (24 May 1819–22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837, and Empress of India from 1 January 1877 until her death. Her reign lasted more than sixty-three years — longer than that of any other British monarch. As well as being Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, she was also the first monarch to use the title Empress of India. The reign of Victoria was marked by a great expansion of the British Empire. The Victorian Era was at the height of the Industrial Revolution, a period of significant social, economic, and technological change in the United Kingdom. Victoria was the last monarch of the House of Hanover; her successor belonged to the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

Her Royal Highness Princess Victoria of Kent was born at Kensington Palace in London in 1819. Victoria's father, the Duke of Kent and Strathearn, was the fourth son of King George III. The Duke of Kent and Strathearn, like many other sons of George III, did not marry during his youth. The eldest son, the Prince of Wales (the future King George IV), did marry, but had only a daughter, Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales. When she then died in 1817, the remaining unmarried sons of King George III scrambled to marry (the Prince Regent and the Duke of York were already married, but estranged from their wives) and father children to provide an heir for the king. At the age of fifty the Duke of Kent and Strathearn married Princess Viktoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, the sister of Princess Charlotte's widower Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfield and widow of Karl, Prince of Leiningen. Victoria, the only child of the couple, was born in Kensington Palace, London on 24 May 1819.

Although christened Alexandrina Victoria, from birth she was formally styled Her Royal Highness Princess Victoria of Kent, but was called Drina within the family. Princess Victoria's father died of pneumonia eight months after she was born. Her grandfather, George III, died blind and insane less than a week later. Princess Victoria's uncle, the Prince of Wales, inherited the Crown, becoming King George IV. Though she occupied a high position in the line of succession, Victoria was taught only German, the first language of both her mother and her governess, during her early years. After reaching the age of three, however, she was schooled in English. She eventually learned to speak Italian, Greek, Latin, and French. Her educator was the Reverend George Davys and her governess was Louise Lehzen.

When Princess Victoria of Kent was eleven years old, her uncle, King George IV, died childless, leaving the throne to his brother, the Duke of Clarence and St Andrews, who became King William IV. As the new king was childless, the young Princess Victoria became heiress-presumptive to the throne. Since the law at that time made no special provision for a child monarch, Victoria would have been eligible to govern the realm as would an adult. In order to prevent such a scenario, Parliament passed the Regency Act 1831, under which it was provided that Victoria's mother, the Duchess of Kent and Strathearn, would act as Regent during the queen's minority. Ignoring precedent, Parliament did not create a council to limit the powers of the Regent.

Princess Victoria met her future husband, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, when she was sixteen years old. Prince Albert was Victoria's first cousin; his father was the brother of her mother. Princess Victoria's uncle, King William IV, disapproved of the match, but his objections failed to dissuade the couple. Many scholars have suggested that Prince Albert was not in love with young Victoria, and that he entered into a relationship with her in order to gain social status (he was a minor German prince) and out of a sense of duty (his family desired the match). Whatever Albert's original reasons for marrying Victoria may have been, theirs proved to be an extremely happy marriage.

While Albert was of the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, it was not clear what his surname was, because like most imperial, royal, princely, and ducal families, his family did not use theirs. Victoria asked her staff to determine what Albert's and now her own marital surname was. After examining records from the Saxe-Coburg-Gotha archives, they reported that her husband's personal surname was Wettin (or von Wettin). 's papers record her dislike of the name. Though rarely publicly used, that remained the Royal Family's personal surname until 1917, when Victoria's grandson King George V merged the Royal House name and family surname, replacing both with one deliberately English-sounding name, Windsor. (In the early 1960s an Order-in-Council partially reversed the decision by granting Queen Elizabeth II's descendants a separate family surname, Mountbatten-Windsor.)

King William IV died at the age of seventy-two on 20 June 1837, leaving the throne to Victoria. As the young queen had just turned eighteen years old, no regency was necessary. By Salic law, no woman could rule Hanover, a realm which had shared a monarch with Britain since 1714. Hanover went not to Victoria, but to her uncle, the Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale, who became King Ernest Augustus of Hanover. As the young queen was as yet unmarried and childless, Ernest Augustus was also the heir-presumptive to the British throne.

When Victoria ascended the throne, the government was controlled by the Whig Party, which had been in power, except for brief intervals, since 1830. The Whig Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, at once became a powerful influence in the life of the politically inexperienced Queen, who relied on him for advice. (Some even referred to Victoria as "Mrs Melbourne".) The Melbourne ministry would not stay in power for long; it was growing unpopular and, moreover, faced considerable difficulty in governing the British colonies. In Canada, the United Kingdom faced an insurrection (see Rebellions of 1837), and in Jamaica, the colonial legislature had protested British policies by refusing to pass any laws. In 1839, unable to cope with the problems overseas, the ministry of Lord Melbourne resigned.

The Queen commissioned Sir Robert Peel, a Tory, to form a new ministry, but was faced with a debacle known as the Bedchamber Crisis. At the time, it was customary for appointments to the Royal Household to be based on the patronage system (that is, for the Prime Minister to appoint members of the Royal Household on the basis of their party loyalties). Many of the Queen's Ladies of the Bedchamber were wives of Whigs, but Sir Robert Peel expected to replace them with wives of Tories. Victoria strongly objected to the removal of these ladies, whom she regarded as close friends rather than as members of a ceremonial institution. Sir Robert Peel felt that he could not govern under the restrictions imposed by the Queen, and consequently resigned his commission, allowing Melbourne to return to office.

The Queen married Prince Albert on 10 February 1840 at the Chapel Royal in St. James's Palace; four days before, Victoria granted her husband the style His Royal Highness. Prince Albert was commonly known as the "Prince Consort", though he did not formally obtain the title until 1857. Prince Albert was never granted a peerage dignity.

During Victoria's first pregnancy, eighteen-year old Edward Oxford attempted to assassinate the Queen whilst she was riding in a carriage with Prince Albert in London. Oxford fired twice, but both bullets missed. He was tried for high treason, but was acquitted on the grounds of insanity. His plea was questioned by many; Oxford may merely have been seeking notoriety. Many suggested that a Chartist conspiracy was behind the assassination attempt; others attributed the plot to supporters of the heir-presumptive, the King of Hanover. These conspiracy theories afflicted the country with a wave of patriotism and loyalty.

The shooting had no effect on the queen's health or on her pregnancy. The first child of the royal couple, named Victoria, was born on 21 November 1840. Eight more children would be born during the exceptionally happy marriage between Victoria and Prince Albert. Albert was not only the Queen's companion, but also an important political advisor, replacing Lord Melbourne as the dominant figure in her life. Having found a partner, Victoria no longer relied on the Whig ladies at her court for companionship. Thus, when Whigs under Melbourne lost the elections of 1841 and were replaced by the Tories under Peel, the Bedchamber Crisis was not repeated. Victoria continued to secretly correspond with Lord Melbourne, whose influence, however, faded away as that of Prince Albert increased.

On 13 June 1842, Victoria made her first journey by train, travelling from Slough railway station (near Windsor Castle) to Bishop's Bridge, near Paddington (in London), in a special royal carriage provided by the Great Western Railway. Accompanying her were her husband and the engineer of the Great Western line, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Three attempts to assassinate the Queen occurred in 1842. On 29 May at St. James's Park, John Francis (most likely seeking to gain notoriety) fired a pistol at the Queen (then in a carriage), but was immediately seized by PC53 William Trounce. He was convicted of high treason, but his death sentence was commuted to transportation for life. Prince Albert felt that the attempts were encouraged by Oxford's acquittal in 1840. On 3 July, just days after Francis' sentence was commuted, another boy, John William Bean, attempted to shoot the Queen. Although his gun was loaded only with paper and tobacco, his crime was still punishable by death. Feeling that such a penalty would be too harsh, Prince Albert encouraged Parliament to pass an act, under which aiming a firearm at the Queen, striking her, throwing any object at her, and producing any firearm or other dangerous weapon in her presence with the intent of alarming her, were made punishable by seven years imprisonment and flogging. Bean was thus sentenced to eighteen months imprisonment; neither he, nor any person who violated the act in the future, was flogged.

Peel's ministry faced a crisis involving the repeal of the Corn Laws. Many Tories (by then known also as Conservatives) were opposed to the repeal, but some Tories (the "Peelites") and most Whigs supported it. Peel resigned in 1846, after the repeal narrowly passed, and was replaced by Lord John Russell. Russell's ministry, though Whig, was not favoured by the Queen. Particularly offensive to Victoria was the Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, who often acted without consulting the Cabinet, the Prime Minister, or the Queen. In 1849, Victoria lodged a complaint with Lord John Russell, claiming that Palmerston had sent official dispatches to foreign leaders without her knowledge. She repeated her remonstrance in 1850, but to no avail. It was only in 1851 that Lord Palmerston was removed from office; he had on that occasion announced the British government's approval for President Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte's coup in France without previously consulting the Prime Minister.

The period during which Russell was prime minister also proved personally distressing to . In 1849, an unemployed and disgruntled Irishman named William Hamilton attempted to alarm the Queen by discharging a powder-filled pistol in her presence. Hamilton was charged under the 1842 act; he pled guilty and received the maximum sentence of seven years of penal transportation. In 1850, the Queen did sustain injury when she was assaulted by a possibly insane ex-Army officer, Robert Pate. As Victoria was riding in a carriage, Pate struck her with his cane, crushing her bonnet and bruising her. Pate was later tried; he failed to prove his insanity, and received the same sentence as Hamilton.

The young fell in love with Ireland, choosing to holiday in Killarney in Kerry, in the process, launching the location as one of the nineteenth century's prime tourist locations. Her love of the island was matched by an initial Irish warmth for the young queen. In 1845, Ireland was hit by a potato blight that over four years cost the lives of over half a million Irish people and saw the emigration of another million. In response to what came to be called the Irish Potato Famine (An Gorta Mor) the queen personally donated £5000 and was involved in various famine charities. Nevertheless the fact that the policies of the ministry of Lord John Russell were widely blamed for exacerbating the severity of the famine impacted on the Queen's popularity. To extreme republicans Victoria came to be called the "Famine Queen", with mythical stories of her donating as little as £5 to famine relief becoming accepted in republican lore.

Victoria's first official visit to Ireland, in 1849, was specifically arranged by Lord Clarendon, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the head of the British administration, to try both to draw attention off the famine and also to alert British politicians through the Queen's presence to the seriousness of the crisis in Ireland. Notwithstanding the negative impact of the famine on the Queen's popularity, she still remained sufficiently popular for nationalists at party meetings to finish by singing God Save the Queen. However by the 1870s and 1880s the monarchy's appeal in Ireland had diminished substantially, partly as a result of Victoria's decision to refuse to visit Ireland in protest at the decision of Dublin Corporation to refuse to congratulate her son, the Prince of Wales, on his marriage to Princess Alexandra of Denmark, or to congratulate the royal couple on the birth of their oldest son, Prince Albert Victor.

Victoria refused repeated pressure from a number of prime ministers, lords lieutenant and even members of the Royal Family, to establish a royal residence in Ireland. Writing in his memoirs, Ireland: Dupe or Heroine? in 1930, Lord Midleton, the former head of the Irish unionist party, described this decision as having proved disastrous to the monarchy and British rule in Ireland.

Victoria paid her last visit to Ireland in 1900, when she came to appeal to Irishmen to join the British Army and fight in the Boer War. Nationalist opposition to her visit was spearheaded by Arthur Griffith, who established an organisation called Cumann na nGaedheal to unite the opposition. Five years later Griffith used the contacts established in his campaign against the queen's visit to form a new political movement, Sinn Fein.

In 1851, the first World Fair, known as the Great Exhibition of 1851, was held. Organised by Prince Albert, the exhibition was officially opened by the Queen on 1 May 1851. Despite the fears of many, it proved an incredible success, with its profits being used to endow the South Kensington Museum (later renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum).

Lord John Russell's ministry collapsed in 1852, when the Whig Prime Minister was replaced by a Conservative, Lord Derby. Lord Derby did not stay in power for long, for he failed to maintain a majority in Parliament; he resigned less than a year after entering office. At this point, Victoria was anxious to put an end to this period of weak ministries. Both the Queen and her husband vigorously encouraged the formation of a strong coalition between the Whigs and the Peelite Tories. Such a ministry was indeed formed, with the Peelite Lord Aberdeen at its head.

One of the most significant acts of the new ministry was to bring the United Kingdom into the Crimean War in 1854, on the side of the Ottoman Empire and against Russia. Immediately before the entry of the United Kingdom, rumours that the Queen and Prince Albert preferred the Russian side diminished the popularity of the royal couple. Nonetheless, Victoria publicly encouraged unequivocal support for the troops. After the conclusion of the war, she instituted the Victoria Cross, an award for valour.

His management of the war in the Crimea questioned by many, Lord Aberdeen resigned in 1855, to be replaced by Lord Palmerston, with whom the Queen had reconciled. Palmerston too was forced out of office due to the unpopular conduct of a military conflict, the Second Opium War, in 1857. He was replaced by Lord Derby. Amongst the notable events of Derby's administration was the Sepoy Mutiny against the rule of the British East India Company over India. After the mutiny was crushed, India was put under the direct rule of the Crown (though the title "Empress of India" was not instituted immediately). Derby's second ministry fared no better than his first; it fell in 1859, allowing Palmerston to return to power.

Widowhood

The Prince Consort died in 1861, devastating Victoria, who entered a semi-permanent state of mourning and wore black for the remainder of her life. She avoided public appearances and rarely set foot inside London in the following years, her seclusion earning her the nickname "Widow of Windsor." She regarded her son, the Prince of Wales, as an indiscreet and frivolous youth, blaming him for his father's death.Victoria began to increasingly rely on a Scottish manservant, John Brown; and a romantic connection and even a secret marriage have been alleged. One recently discovered diary records a supposed deathbed confession by the Queen's private chaplain in which he admitted to a politician that he had presided over a clandestine marriage between Victoria and John Brown. Not all historians trust the reliability of the diary. However, when Victoria's corpse was laid in its coffin, two sets of mementos were placed with her, at her request. By her side was placed one of Albert's dressing gowns while in her left hand was placed a piece of Brown's hair, along with a picture of him. Rumours of an affair and marriage earned Victoria the nickname "Mrs Brown".

Victoria's isolation from the public greatly diminished the popularity of the monarchy, and even encouraged the growth of the republican movement. Although she did perform her official duties, she did not actively participate in the government, remaining secluded in her royal residences, Balmoral in Scotland or her residence at Osborne in the Isle of Wight. Meanwhile, one of the most important pieces of legislation of the nineteenth century — the Reform Act 1867 — was passed by Parliament. Lord Palmerston was vigorously opposed to electoral reform, but his ministry ended upon his death in 1865. He was followed by Lord Russell (the former Lord John Russell), and afterwards by Lord Derby, during whose ministry the Reform Act was passed.

In 1868, a man who would prove to be Victoria's favourite Prime Minister, the Conservative Benjamin Disraeli, entered office. His ministry, however, soon collapsed, and he was replaced by William Ewart Gladstone, a member of the Liberal Party (as the Whig-Peelite Coalition had become known). Gladstone was famously at odds with both Victoria and Disraeli during his political career. She once remarked that she felt he addressed her as though she were a public meeting. The Queen disliked Gladstone, as well as his policies, as much as she admired Disraeli. It was during Gladstone's ministry, in the early 1870s, that the Queen began to gradually emerge from a state of perpetual mourning and isolation. With the encouragement of her family, she became more active.

In 1872, Victoria endured her sixth encounter involving a gun. As she was dismounting a carriage, a seventeen-year old Irishman, Arthur O'Connor, rushed towards her with a pistol in one hand and a petition to free Irish prisoners in the other. The gun was not loaded; the youth's aim was most likely to alarm Victoria into accepting the petition. John Brown, who was at the Queen's side, knocked the boy to the ground before Victoria could even view the pistol; he was rewarded with a gold medal for his bravery. O'Connor was sentenced to penal transportation and to corporal punishment, as allowed by the Act of 1842, but Victoria remitted the latter part of the sentence.

Lord Beaconsfield's administration fell in 1880 when the Liberals won the general election of that year. Gladstone had relinquished the leadership of the Liberals four years earlier and the Queen invited Lord Hartington, Liberal leader in the Commons, to form a ministry. However Lord Hartington declined the opportunity, arguing that no Liberal ministry could work without Gladstone and he would serve under no-one else, and Victoria could do little but appoint Gladstone Prime Minister.

The last of the series of attempts on Victoria's life came in 1882. A Scottish madman, Roderick Maclean, fired a bullet towards the Queen, then seated in her carriage, but missed. Since 1842, each individual who attempted to attack the Queen had been tried for a misdemeanour (punishable by seven years of penal servitude), but Maclean was tried for high treason (punishable by death). He was acquitted, having been found insane, and was committed to an asylum. Victoria expressed great annoyance at the verdict of "not guilty, but insane," and encouraged the introduction of the verdict of "guilty, but insane" in the following year.

Victoria's conflicts with Gladstone continued during her later years. She was forced to accept his proposed electoral reforms, including the Representation of the People Act 1884, which considerably increased the electorate. Gladstone's government fell in 1885, to be replaced by the ministry of a Conservative, Lord Salisbury. Gladstone returned to power in 1886, and he introduced the Irish Home Rule Bill, which sought to grant Ireland a separate legislature. Victoria was opposed to the bill, which she believed would undermine the British Empire. When the bill was rejected by the House of Commons, Gladstone resigned, allowing Victoria to appoint Lord Salisbury to resume the premiership.

The Royal Family in 1880.In 1887, the United Kingdom celebrated Victoria's Golden Jubilee. Victoria marked 20 June 1887 — the fiftieth anniversary of her accession — with a banquet, to which fifty European kings and princes were invited. Although she cannot have been aware of it, there was a plan by Irish terrorists to blow up Westminster Abbey while the Queen attended a service of thanksgiving. This assassination attempt, when it was discovered, became known as The Jubilee Plot. On the next day, she participated in a procession that, in the words of Mark Twain, "stretched to the limit of sight in both directions." At the time, Victoria was an extremely popular monarch. The scandal of a rumoured relationship with her servant had been quieted following John Brown's death in 1883, allowing the Queen to be perceived as a symbol of morality.

Victoria was required to tolerate a ministry of William Ewart Gladstone one more time, in 1892. After the last of his Irish Home Rule Bills was defeated, he retired in 1894, to be replaced by the Imperialist Liberal Lord Rosebery. Lord Rosebery was succeeded in 1895 by Lord Salisbury, who served for the remainder of Victoria's reign.

On 22 September 1896, Victoria surpassed George III as the longest-reigning monarch in English, Scottish, or British history. In accordance with the Queen's request, all special public celebrations of the event were delayed until 1897, the Queen's Diamond Jubilee. The Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, proposed that the Jubilee be made a festival of the British Empire. Thus, the Prime Ministers of all the self-governing colonies were invited along with their families. The procession in which the Queen participated included troops from each British colony and dependency, together with soldiers sent by Indian Princes and Chiefs (who were subordinate to Victoria, the Empress of India). The Diamond Jubilee celebration was an occasion marked by great outpourings of affection for the septuagenarian Queen, who was by then confined to a wheelchair.

During Victoria's last years, the United Kingdom was involved in the Boer War, which received the enthusiastic support of the Queen. Victoria's personal life was marked by many personal tragedies, including the death of her son, the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the fatal illness of her daughter, the Empress of Germany, and the death of two of her grandsons. Her last ceremonial public function came in 1899, when she laid the foundation stone for new buildings of the South Kensington Museum, which became known as the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Following a custom she maintained throughout her widowhood, Victoria spent Christmas in Osborne House (which Prince Albert had designed himself) on the Isle of Wight. She died there on 22 January 1901, having reigned for sixty-three years, seven months, and two days, more than any British monarch before or since. Her funeral occurred on 2 February; after two days of lying-in-state, she was interred in the Frogmore Mausoleum beside her husband.

Victoria was succeeded by her eldest son, the Prince of Wales, who reigned as King Edward VII. Victoria's death brought an end to the rule of the House of Hanover in the United Kingdom; King Edward VII, like his father Prince Albert, belonged to the House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. King Edward VII's son and successor, King George V, changed the name of the Royal House to Windsor during the First World War. (The name "Saxe-Coburg-Gotha" was associated with the enemy of the United Kingdom during the war, Germany, led by her grandson Kaiser Wilhelm II.)

A statue of Victoria stands in the city centre of Bristol, England.was Britain's first modern monarch. Previous monarchs had been active players in the process of government. A series of legal reforms saw the House of Commons' power increase at the expense of the Lords and the monarchy, with the monarch's role becoming more symbolic. From Victoria's reign on, the monarch in Walter Bagehot's words, had "the right to be consulted, the right to advise, and the right to warn."

Victoria's monarchy became more symbolic than political, with a strong emphasis on morality and family values, in contrast to the sexual, financial and personal scandals that had been associated with previous members of the House of Hanover and which had discredited the monarchy. Victoria's reign created for Britain the concept of the 'family monarchy' with which the burgeoning middle classes could identify.

Internationally Victoria was a major figure, not just in image or in terms of Britain's influence through the empire, but also because of family links throughout Europe's royal families, earning her the affectionate nickname "the grandmother of Europe". An example of that status can be seen in the fact that three of the main monarchs with countries involved in the First World War on opposite sides were themselves either grandchildren of Victoria's or married to a grandchild of hers. Eight of Victoria's nine children married members of European royal families, and the other, Princess Louise, married a Scottish Duke.

Victoria was the first known carrier of haemophilia in the royal line, but it is unclear how she acquired it. She may have acquired it as a result of a sperm mutation, her father having been fifty-two years old when Victoria was conceived. It had also been rumoured that the Duke of Kent was not the biological father of Victoria, and that she was in fact the daughter of her mother's Irish-born private secretary and reputed lover, Sir John Conroy. While there is some evidence as to the allegation of a relationship between the duchess and Conroy (Victoria herself claimed to the Duke of Wellington to have witnessed an incident between them) Conroy's medical history shows no evidence of the existence of haemophilia in his family, nor is it normally passed on the male side of the family. It is much more likely that she acquired it from her mother, though there is no known history of haemophilia in her maternal family. Though she did not suffer from the disease, she passed it on to Princess Alice and Princess Beatrice as carriers, and Prince Leopold was affected with the disease. The most famous haemophilia victim among her descendants was her great-grandson, Alexei, Tsarevich of Russia. However, Victoria's line of haemophilia has now probably been eliminated. There could still be a surviving branch in the royal family of Spain, but as of 2005, the disease has not surfaced.

As of 2004, the European monarchs and former monarchs descended from Victoria are: the Queen of the United Kingdom, the King of Norway, the King of Sweden, the Queen of Denmark, the King of Spain, the King of the Hellenes (deposed) and the King of Romania (deposed).

experienced unpopularity during the first years of her widowhood, but afterwards became extremely well-liked during the 1880s and 1890s. In 2002, the British Broadcasting Corporation conducted a poll regarding the 100 Greatest Britons; Victoria attained the eighteenth place.

Princess Alexandrina Victoria was not only born to be Queen of England: she was conceived to be Queen. Once Princess Charlotte, the only legitimate child of the Prince of Wales, the future George IV, died in childbirth late in 1817, her son stillborn, the nation was plunged into mourning and her unmarried uncles stirred into competition to sire an heir to the throne. With the Prince of Wales, Prince Regent for his insane father, George III, separated from the future (but uncrowned) Queen Caroline, no lawful successor would come that way. To solve the succession dilemma, the royal brothers, princes of the blood, most of them with mistresses and illegitimate progeny, were ordered to marry and beget, with their reward for success a promised cancellation of their heavy debts.

Although William IV, the Duke of Clarence (1830-37), duly married a minor German princess, no child of his survived early infancy. Next in line, Edward, Duke of Kent, would jettison his mistress of many years and marry the widowed Victoire, Duchess of Amorbach, who had proved her fertility during her first marriage. When she became pregnant, it became necessary, once she could travel, to leave her small German dukedom and give birth on English soil to establish unquestionable credentials for the child's likely inheritance. But beset by debt unresolved by the Regent, the Duke encountered delays in raising the money to get his entourage across the Channel. On 28 March 1819, in her eighth month, the Duchess set off, arriving at Dover on 24 April, barely in time for the accouchement. At Kensington Palace, in apartments reluctantly granted by the Regent, who disliked his improvident brother, the future queen was born on 24 May. The new princess was christened a month later, with none of the usual royal names available to her parents because of the Regent's refusal to permit another Charlotte or Elizabeth or Georgina.

Since the Russian tsar, Alexander I, was godfather in absentia, his name was available, and even as late as the morning of her accession, at eighteen, on June 20, 1837, the public was unsure of the official name of the new queen. She had always been known as Victoria, however, and was so proclaimed. Fatherless as an infant-her father had died on January 23, 1820, only six days before his own father, George III-she was dominated by her ambitious mother, who hoped for a Regency for herself if William IV died before Victoria's eighteenth birthday. Stubbornly, the ailing king held on just long enough for his niece to reign in her own right. But she proved wilful and difficult, creating embarrassments at Court that led her advisers, notably the avuncular Viscount Melbourne, the Prime Minister, to press her to marry. A husband might control her, and in any case the nation needed a guaranteed succession.

Victoria's mother and her Coburg brothers arranged to keep the prospective marriage within the family. Yet they were assisted by the dearth of acceptable Protestant candidates among European royals, some of whom the young Queen interviewed to her disappointment. Late in 1839, however, when she met Prince Albert, the younger son of her uncle Ernest, the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, for only the second time (three years earlier he had been a callow teen-ager), she was smitten. A student at the University of Bonn, he was clearly her intellectual superior-and, she thought, beautiful. She proposed (he could not, as she was Queen), and they were married in February 1840.

At first, Albert only wielded the blotting paper as she signed documents. He was uneasy about his lack of occupation and status; but he had been employed to ensure the succession. Biology thereafter ensured his role. When Victoria became so visibly pregnant that she could not appear ceremonially, Albert assumed her functions. Once she became heavy and listless, he also became, in effect, the senior partner (although five months her junior) in a dual monarchy. After nine children through 1856, he had established himself as her primary adviser, often drafting memoranda that she recopied in her own hand and signed. Impressed by his abilities, the aging Duke of Wellington, eager to retire, even invited him to become chief of the army, but Albert, an honorary field marshal, resisted the temptation, explaining that he had to subsume his personality and his ambitions in the interests of the Queen.

But for the period of the Crimean War (1853-54), when the couple, especially Albert, were suspected falsely of Russian sympathies, the dual monarchy worked efficiently. England in any case was evolving, after the first Reform Bill (1832), into a constitutional monarchy, with the sovereign's powers becoming more moral and symbolic than legislative. The authority of the throne now rested more and more in popular respect for its occupant. That situation ended abruptly when Albert, at 42 in December 1861, died of what was very likely stomach cancer. His incompetent physicians called it typhoid, but no other cases existed in the area, rendering that diagnosis suspect, and although Victoria knew nothing of his long-standing symptoms, and was prostrated by his death, Albert was aware that he had been suffering from something inoperable.

The Prince Consort's death altered the monarchy irreparably. Victoria was inconsolable, out of shock, out of loss, and out of her realization that she had depended so long upon Albert's advice and support that she was unsure she could be sovereign alone. She went into purdah, for years failing to perform even her ceremonial functions on grounds that she was in perpetual mourning. The monarchy accordingly declined in authority and in esteem, and public perception was summed up by a cartoon in the press that showed the royal robes draped over an empty throne. Twenty at Albert's death-the same age as were Victoria and Albert at their marriage, Albert Edward ("Bertie"), the Prince of Wales was given no compensatory duties to fill some of the void left by his father's death and his mother's disappearance into grief. Just before his father's last illness the young prince had been discovered in a liaison with a lady of the evening, and Victoria believed that the shock and the potential scandal had led to Albert's decline. Bertie was pronounced as unfit to be king, and unfit to assume any national role. Bertie's lack of anything to do, and his incapacity to invent serious work for himself led to his life as playboy prince, despite a marriage that was supposed to settle him down. (Alexandra was beautiful but brainless, with no ability to rein in her husband.) His increasing notoriety as "Edward the Caresser" (in Henry James's phrase) and Victoria's invisibility as sovereign would lead to a decade of republican agitation that ended fortuitously in 1871 when Bertie came down with authentic typhoid fever, and nearly died. The weeks of public agitation over his possible demise, and his seemingly miraculous recovery, exploded the thin but widespread anti-monarchical sentiment in Britain. It did not make the Prince more moral or even more circumspect, but the second ministry of Benjamin Disraeli beginning in 1874 engineered the rehabilitation of the throne by drawing the queen back into public life and in finding acceptable roles for her heir.

The costly Indian Mutiny in 1856-57 had led to reorganization of imperial rule in the subcontinent, and on Victoria's return to visibility in the 1870s she began to yearn for a title that would prevent her eldest daughter, Vicky, married to the heir to the German throne, from-as empress--outranking her proud mother. The Queen wanted to be Empress of India, and as part of the price for her increasing public role pressed Disraeli into arranging an imperial title representing the jewel in her crown. At about the same time, the Prince of Wales, eager for a junket to India with his cronies, to hunt elephants and tigers, convinced the Prime Minister to arrange a royal tour. Despite all likelihood that the princely progress would be a disaster, it was a triumph, demonstrating Bertie's diplomatic and impresario qualities, which he would employ with brio thereafter. As he was embarking home, news arrived that the Queen had indeed been styled Empress of India.

Fortunately for the Queen's reputation, her Scots manservant John Brown had died early in 1883. For Victoria, Brown's much-lamented passing severed a link with Albert in life and in death. He had been the Prince's gillie, and to extricate the Queen from self-imposed purdah her doctors recommended importing Brown from Balmoral to care for her personal horses and get her out riding. The gruff, bearded Scot became her favorite, accompanying her publicly almost everywhere. He also become a barrier -- as she wanted -- to intrusions from staff, and even from her children. (They despised him.) He sat in on table-turning seances in that heyday of spiritualism to help summon up a very dubious hint of the Prince. She despised smoking but Brown could appear before her in a haze of tobacco, and often tipsy as well with whiskey -- and he taught Victoria how to put a nip of Scotch in her tea. Class vanished. In an age of sentimental effusions, she sent him valentines by post, and awarded him a special medal for loyal service to the Queen.

Rumor had it that he was sexually intimate with her, even that they were secretly married, and in 1869 a scandal sheet claimed that the Queen (in her 50th year) had gone to Switzerland to covertly bear his child. Her very openness about Brown belied such intimacies, but without a husband to embrace she seems to have savored being clutched by him as he helped on and off her horses, and in and out of her carriages. When he was dying, protocol forbade her to visit him (contrary to an episode in the film "Mrs. Brown"), and in any event a fall had lamed one of her knees, and she could not have climbed stairs to his quarters. "If he had been a more ambitious man," said Sir William Knollys, the Prince of Wales's comptroller, of Brown, "there is no doubt . . . he might have meddled in more important matters. I presume the family will rejoice at his death, but I think very probably they are shortsighted." Yet Brown's disappearance from the Victorian scene helped restore the Queen's public image. She could better embody middle-class values and become the symbolic mother of her country.

The 1880s and 1890s were decades of Victoria's increasing visibility as symbol of Britain and of Empire, as-with the Prince of Wales often acting as impresario-she celebrated her Golden Jubilee as Queen, and then, turning it into an imperial festival, she marked her Diamond Jubilee in 1897. She had become an icon of Empire, ironically just as the Anglo-Boer War was about to erupt in South Africa, adding to the red areas on the globe but embarrassing the nation by showing how difficult it was to win and control colonies in a dawning age of nationalism. In her waning years, Victoria, calling herself a soldier's daughter, went out, although wheelchair-bound by age and frailty, to bid departing troops godspeed.

The war was still ongoing when, incapacitated by a series of small strokes, she died in January 1901, the first month of the new century. But Victoria's world of simple values and simple loyalties, and her rigid view of the Crown, had preceded her in death.

Victoria was born at Kensington Palace, London, on 24 May 1819. She was the only daughter of Edward, Duke of Kent, fourth son of George III. Her father died shortly after her birth and she became heir to the throne because the three uncles who were ahead of her in succession - George IV, Frederick Duke of York, and William IV - had no legitimate children who survived.

Warmhearted and lively, Victoria had a gift for drawing and painting; educated by a governess at home, she was a natural diarist and kept a regular journal throughout her life. On William IV's death in 1837, she became Queen at the age of 18.

is associated with Britain's great age of industrial expansion, economic progress and, especially, empire. At her death, it was said, Britain had a worldwide empire on which the sun never set.

In the early part of her reign, she was influenced by two men: her first Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, and her husband, Prince Albert, whom she married in 1840. Both men taught her much about how to be a ruler in a 'constitutional monarchy' where the monarch had very few powers but could use much influence.

Albert took an active interest in the arts, science, trade and industry; the project for which he is best remembered was the Great Exhibition of 1851, the profits from which helped to establish the South Kensington museums complex in London.

Her marriage to Prince Albert brought nine children between 1840 and 1857. Most of her children married into other Royal families of Europe.

Edward VII (born 1841), married Alexandra, daughter of Christian IX of Denmark. Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh and of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (born 1844) married Marie of Russia. Arthur, Duke of Connaught (born 1850) married Louise Margaret of Prussia. Leopold, Duke of Albany (born 1853) married Helen of Waldeck-Pyrmont.

Victoria, Princess Royal (born 1840) married Friedrich III, German Emperor. Alice (born 1843) married Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine. Helena (born 1846) married Christian of Schleswig-Holstein. Louise (born 1848) married John Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll. Beatrice (born 1857) married Henry of Battenberg.

Victoria bought Osborne House (later presented to the nation by Edward VII) on the Isle of Wight as a family home in 1845, and Albert bought Balmoral in 1852.

Victoria was deeply attached to her husband and she sank into depression after he died, aged 42, in 1861. She had lost a devoted husband and her principal trusted adviser in affairs of state. For the rest of her reign she wore black.

Until the late 1860s she rarely appeared in public; although she never neglected her official Correspondence, and continued to give audiences to her ministers and official visitors, she was reluctant to resume a full public life.

She was persuaded to open Parliament in person in 1866 and 1867, but she was widely criticised for living in seclusion and quite a strong republican movement developed.

Seven attempts were made on Victoria's life, between 1840 and 1882 - her courageous attitude towards these attacks greatly strengthened her popularity.

With time, the private urgings of her family and the flattering attention of Benjamin Disraeli, Prime Minister in 1868 and from 1874 to 1880, the Queen gradually resumed her public duties.

In foreign policy, the Queen's influence during the middle years of her reign was generally used to support peace and reconciliation. In 1864, Victoria pressed her ministers not to intervene in the Prussia-Austria-Denmark war, and her letter to the German Emperor (whose son had married her daughter) in 1875 helped to avert a second Franco-German war.

On the Eastern Question in the 1870s - the issue of Britain's policy towards the declining Turkish Empire in Europe - Victoria (unlike Gladstone) believed that Britain, while pressing for necessary reforms, ought to uphold Turkish hegemony as a bulwark of stability against Russia, and maintain bi-partisanship at a time when Britain could be involved in war.

Victoria's popularity grew with the increasing imperial sentiment from the 1870s onwards. After the Indian Mutiny of 1857, the government of India was transferred from the East India Company to the Crown with the position of Governor General upgraded to Viceroy, and in 1877 Victoria became Empress of India under the Royal Titles Act passed by Disraeli's government.

During Victoria's long reign, direct political power moved away from the sovereign. A series of Acts broadened the social and economic base of the electorate.

These acts included the Second Reform Act of 1867; the introduction of the secret ballot in 1872, which made it impossible to pressurise voters by bribery or intimidation; and the Representation of the Peoples Act of 1884 - all householders and lodgers in accommodation worth at least £10 a year, and occupiers of land worth £10 a year, were entitled to vote.

Despite this decline in the Sovereign's power, Victoria showed that a monarch who had a high level of prestige and who was prepared to master the details of political life could exert an important influence.

This was demonstrated by her mediation between the Commons and the Lords, during the acrimonious passing of the Irish Church Disestablishment Act of 1869 and the 1884 Reform Act.

It was during Victoria's reign that the modern idea of the constitutional monarch, whose role was to remain above political parties, began to evolve. But Victoria herself was not always non-partisan and she took the opportunity to give her opinions, sometimes very forcefully, in private.

After the Second Reform Act of 1867, and the growth of the two-party (Liberal and Conservative) system, the Queen's room for manoeuvre decreased. Her freedom to choose which individual should occupy the premiership was increasingly restricted.

In 1880, she tried, unsuccessfully, to stop William Gladstone - whom she disliked as much as she admired Disraeli and whose policies she distrusted - from becoming Prime Minister. She much preferred the Marquess of Hartington, another statesman from the Liberal party which had just won the general election. She did not get her way.

She was a very strong supporter of Empire, which brought her closer both to Disraeli and to the Marquess of Salisbury, her last Prime Minister.

Although conservative in some respects - like many at the time she opposed giving women the vote - on social issues, she tended to favour measures to improve the lot of the poor, such as the Royal Commission on housing. She also supported many charities involved in education, hospitals and other areas.

Victoria and her family travelled and were seen on an unprecedented scale, thanks to transport improvements and other technical changes such as the spread of newspapers and the invention of photography. Victoria was the first reigning monarch to use trains - she made her first train journey in 1842.

In her later years, she almost became the symbol of the British Empire. Both the Golden (1887) and the Diamond (1897) Jubilees, held to celebrate the 50th and 60th anniversaries of the queen's accession, were marked with great displays and public ceremonies. On both occasions, Colonial Conferences attended by the Prime Ministers of the self-governing colonies were held.

Despite her advanced age, Victoria continued her duties to the end - including an official visit to Dublin in 1900. The Boer War in South Africa overshadowed the end of her reign. As in the Crimean War nearly half a century earlier, Victoria reviewed her troops and visited hospitals; she remained undaunted by British reverses during the campaign: 'We are not interested in the possibilities of defeat; they do not exist.'

Victoria died at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, on 22 January 1901 after a reign which lasted almost 64 years, the longest in British history.

She was buried at Windsor beside Prince Albert, in the Frogmore Royal Mausoleum, which she had built for their final resting place. Above the Mausoleum door are inscribed Victoria's words: 'farewell best beloved, here at last I shall rest with thee, with thee in Christ I shall rise again'.