Algernon Swinburne

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

April 5, 1837, London, England, 5:00 AM, LMT. (Source: Lois Rodden cites Lockhard who quotes Algernon Swinburn by J.O. Fuller, {1968} Sabian Symbols gives the same time) Died, April 10, 1909, 10:00 AM

(Ascendant, Pisces with Uranus in Pisces, H12; MC, Sagittarius; Sun conjunct Moon and Pluto, all in Aries, with Mercury conjunct Venus, also in Aries; Mars conjunct Jupiter in Taurus; Saturn in Scorpio; Neptune in Aquarius; NN in Taurus)

English poet of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Unconventional in his views, and personal life; shocked society with his Poems and Ballads and his play Atlanta and Calydon. Dissipation undermined his health; lived a quiet life after 1880.(Do not confuse with Gerard Manly Hopkins)

Hope thou not much, and fear thou not at all.

On the mountains of memory, by the world’s wellsprings,

In all men’s eyes,

Where the light of the life of him is on all past things,

Death only dies.Love is a barren sea, bitter and deep;

And though she saw all heaven in flower above,

She would not love.His speech is a burning fire;

With his lips he travaileth;

In his heart is a blind desire,

In his eyes foreknowledge of death:

He weaves, and is clothed with derision;

Sows, and he shall not reap;

His life is a watch or a vision

Between a sleep and a sleep.Come with bows bent and with emptying of quivers,

Maiden most perfect,lady of light, Before the beginning of years

There came to the making of man

Time, with a gift of tears;

Grief, with a glass that ran;I shall die as my fathers died, and sleep as they sleep; even so.

For the glass of the years is brittle wherein we gaze for a span;

A little soul for a little bears up this corpse which is man.

So long I endure, no longer; and laugh not again, neither weep.

For there is no God found stronger than death; and death is a sleep.Doubt is faith in the main: but faith, on the whole, is doubt;

We cannot believe by proof: but could we believe without?O sleepless heart and sombre soul unsleeping,

That were athirst for sleep and no more life

And no more love, for peace and no more strife!I am sick of singing; the bays burn deep and chafe: I am fain

To rest a little from praise and grievous pleasure and pain.

Algernon Charles Swinburne was born April 5, 1837 in Grosvenor Place, London, but spent most of his boyhood on the Isle of Wight, where both his parents and grandparents had homes. With Shelley and Byron, he is one of the very few poets since the days of Raleigh and Sidney to come from the aristocracy: his father was an admiral and his maternal grandfather the third earl of Ashburnham. He was very close to his other grandfather, who was born and brought up in France and continued to think and dress like a French nobleman of the ancien régime (the days before the Revolution). He and the poet's mother trained young Algernon in French and Italian.

In religion, the Swinburnes were true to their class, meaning that they were High Church Anglicans (see Church of England), and the poet had a Bible reader's detailed knowledge of the scriptures and of standard interpretative methods, including typology, prophecy, and apocalyptics. His treatment of Christianity seems a characteristically idiosyncratic one -- that is, although he delighted in opposing organized religion and savagely attacked the Roman Catholic Church for its political role in a divided Italy, he makes detailed use of biblical allusion, though often for blasphemous ends. Although Algernon turned to nihilism while at Oxford, he never became indifferent to religion, as "Hymn to Proserpine" (text of poem) and "Hertha" make clear.

Growing up, he had a very close relationship with a cousin, Mary Gordon, and was disconsolate when she married. At Oxford he met nearly everyone who would influence his later life, including Rossetti, Morris, and Burne-Jones, who in 1857 were painting their Arthurian murals on the walls of the Oxford Union, and Benjamin Jowett, the master of Balliol College, who recognized his poetic talent and tried to keep him from being expelled when he began celebrating Orsini, the Italian patriot who attempted to assassinate Napoleon III in 1858. Leaving Oxford in 1860, he became very friendly with the Rossettis. After Elizabeth Siddall's (Mrs. Rossetti)'s death in 1862, he and Rossetti moved to Tudor House, 16 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea.

Swinburne possessed a curious combination of frail health and strength. He was small (just over 5 feet tall) and slightly built, but an excellent swimmer and the first to climb Culver Cliff on the Isle of Wight. He had an extremely excitable disposition: people who met him described him as a "demoniac boy" who would go skipping about the room declaiming poetry at the top of his voice. In this as in many things, he seems to have eschewed moderation. Once or twice he had fits, perhaps epileptic, in public; but he made this condition much worse by drinking past excess to unconsciousness. More than once while he was living with Rossetti he was delivered to the door in the small of the night, dead drunk. Throughout the 1860s and '70s he rode an alcoholic cycle of dissolution, collapse, drying out at home in the country, then returning to London where he would begin all over again.

Although some of his work had already appeared in periodicals, Atalanta in Calydon (1865) was the first poem to come out under his name and was received enthusiastically. "Laus Veneris" and Poems and Ballads (1866), with their sexually charged passages, were attacked all the more violently as a result. Swinburne's meeting in 1867 with his long-time hero Mazzini, the Italian patriot living in England in exile, led to the more political Songs before Sunrise.

His mania for masochism, particularly flagellation, probably began at Eton and was encouraged by his later friendships with Richard Monckton Milnes (one of Tennyson's fellow Apostles), who introduced him to the works of the Marquis de Sade, and Richard Burton, the Victorian explorer and adventurer. Some gamey stories survive from the year or so that he spent living at 16 Cheyne Walk with Rossetti: according to one, Rossetti once had to tell him to keep down the noise--he and a boyfriend had been sliding naked down the bannisters and disturbing Rossetti's painting. In another, Rossetti gave to Adah Menken, the American circus rider, to introduce Swinburne to heterosexual love. She returned it because, she said, "I can't make him understand that biting's no use." He took a sardonic delight in what the critic and biographer, Cecil Lang, calls "Algernonic exaggeration": When people began to talk scathingly about his homosexuality and other sexual proclivities, he circulated a story that he had engaged in pederasty and bestiality with a monkey--and then ate it. How many of the stories were true and how many inventive fiction is still unclear. Oscar Wilde, thoroughly capable of inventing his own interesting fictions, called him "a braggart in matters of vice, who had done everything he could to convince his fellow citizens of his homosexuality and bestiality without being in the slightest degree a homosexual or a bestializer."

In 1879, with Swinburne nearly dead from alcoholism and dissolution, his legal advisor Theodore Watts-Dunton took him in, and was successful in getting him to adopt a healthier style of life. Swinburne lived the rest of his days at Watts-Dunton's house outside London. He saw less and less of his old friends, who thought him "imprisoned" at The Pines, but his growing deafness accounts for some of his decreased sociability. He died of influenza in 1909.

It is clear that Swinburne had an addictive personality, one nearly incapable of moderation. His criticism is perceptive and useful but suffers from praise too lavish of the things he liked and attacks too vituperative on those that he didn't. His poetry follows the by now standard pattern of early flourish and later decline; some of the fresher pieces in the second and third series of Poems and Ballads (1878 and 1889) were actually written during his days at Oxford. Nevertheless, his last collection, A Channel Passage, has some lovely poems, including "The Lake of Gaube." He is best remembered as the supreme technician in metre, with a versatility which exceeds even Tennyson's, but which lacks a corresponding emotional range. His obsessions are not widely enough shared; and if he can not shock us by the strangeness of his desires nor the shrillness of his anti-theistical exclamations, often too little remains.

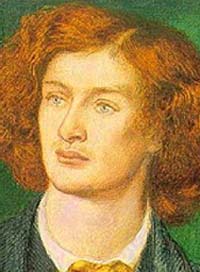

Algernon Swinburne, detail of his portrait by RossettiAlgernon Charles Swinburne (April 5, 1837 – April 10, 1909) was a Victorian era English poet. His poetry was highly controversial in its day, much of it containing recurring themes of sadomasochism, death-wish, lesbianism and irreligion.

Swinburne was born in London, and raised on the Isle of Wight, and at Capheaton Hall, near Wallington, Northumberland. He attended Eton college and then Balliol College, Oxford but had the rare distinction (like Oscar Wilde) of being rusticated from the university in 1859. He was associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, and counted among his best friends Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

He is considered a decadent poet, although he perhaps professed to more vice than he actually indulged in, a fact which Oscar Wilde famously and acerbically commented upon.

Many of his early and still admired poems evoke the Victorian fascination with the Middle Ages, and some of them are explicitly medieval in style, tone and construction, including "The Leper," "Laus Veneris," and "St Dorothy".

He was an alcoholic and a highly excitable character. His health suffered as a result, until he finally had a mental and physical breakdown and was taken into care by his friend Theodore Watts, who looked after him for the rest of his life in Putney. Thereafter he lost his youthful rebelliousness and developed into a figure of social respectability.

His mastery of vocabulary, rhyme and metre arguably put him among the most talented English language poets in history, although he has also been criticized for his florid style and word choices that only fit the rhyme scheme rather than contributing to the meaning of the piece. He is the virtual star of the third volume of George Saintsbury's famous History of English Prosody, and A. E. Housman, a more measured and even somewhat hostile critic, devoted paragraphs of praise to his rhyming ability.

Swinburne's work was once quite popular among undergraduates at Oxford and Cambridge, though today it has largely gone out of fashion. This largely mirrors the popular and academic consensus regarding his work as well, although his Poems and Ballads, First Series and his Atalanta in Calydon have never been out of critical favor.

It was Swinburne's misfortune that the two works, published when he was nearly 30, soon established him as England's premier poet, the successor to Alfred, Lord Tennyson and Robert Browning. This was a position he held in the popular mind until his death, but sophisticated critics like A. E. Housman felt, rightly or wrongly, that the job of being one of England's very greatest poets was beyond him. Swinburne may have felt this way himself. He was a highly intelligent man and in later life a much-respected critic, and he himself believed that the older a man was, the more cynical and less trustworthy he became. This of course created problems for him as he aged.

After the first Poems and Ballads, Swinburne's later poetry is devoted more to philosophy and politics (notably, in favour of the unification of Italy, particularly in the volume Songs before Sunrise). He does not stop writing love poetry entirely, but the content is much less shocking. His versification, and especially his rhyming technique, remain in top form to the end.

Works include: Atalanta in Calydon, Tristram of Lyonesse, Poems and Ballads (series I, II and III -- these contain most of his more controversial works), Songs Before Sunrise, and Lesbia Brandon (published posthumously).

T.S. Eliot, reading Swinburne's essays on the Shakespearean and Jonsonian dramatists in The Contemporaries of Shakespeare and The Age of Shakespeare and Swinburne's books on Shakespeare and Jonson, found that as a poet writing notes on poets, he had mastered his material and was "a more reliable guide to them than Hazlitt, Coleridge, or Lamb," Swinburne's three Romantic predecessors, though he characterized Swinburne's prose as "the tumultuous outcry of adjectives, the headstrong rush of undisciplined sentences, are the index to the impatience and perhaps laziness of a disorderly mind."

Trivia

Ernest Wheldrake was a fictional character invented by Swinburne, who reviewed imaginary works by him. This was as a satire on the spasmodic poets. Wheldrake is also a character used by Michael Moorcock in his fiction.

"A Cameo," a sonnet by Swinburne, is quoted by Mrs. Highcamp in the grand dinner scene of Kate Chopin's novella The Awakening. "There was a graven image of Desire/Painted with red blood on a ground of gold."

Algernon's poem, "The Oblation" is quoted by the character Buck Mulligan in James Joyce's Ulysses. Buck Mulligan jestingly quotes it to the milk woman as he pays her. "Ask nothing more of me, sweet./All I can give you I give."

The Polish blackened death metal band Behemoth on their 2004 album Demigod cite Swinburne's work as being the source for the lyrics to the track "Before the Æons Came".