Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

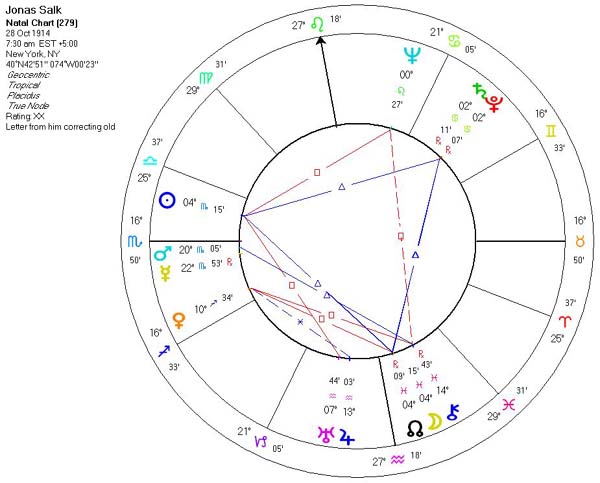

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

I have had dreams and I have had nightmares, but I have conquered my nightmares because of my dreams.

It is always with excitement that I wake up in the morning wondering what my intuition will toss up to me, like gifts from the sea. I work with it and rely on it. It's my partner.

(Mercury in Scorpio. Neptune in Leo in 9th house. Uranus conjunct Jupiter in Aquarius. North Node conjunct Moon in Pisces.)Life is an error-making and an error-correcting process, and nature in marking man's papers will grade him for wisdom as measured both by survival and by the quality of life of those who survive.

(Uranus conjunct Jupiter in Aquarius)It is courage based on confidence, not daring, and it is confidence based on experience.

(Mars & Mercury in Scorpio conjunct Ascendant)I feel that the greatest reward for doing is the opportunity to do more.

Intuition will tell the thinking mind where to look next. Jonas Salk

(Uranus in 3rd house)There is hope in dreams, imagination, and in the courage of those who wish to make those dreams a reality.

(Scorpio Sun T-squaring Neptune & Uranus)Our greatest responsibility is to be good ancestors. Jonas Salk

(Saturn in Cancer conjunct Pluto)This is perhaps the most beautiful time in human history; it is really pregnant with all kinds of creative possibilities made possible by science and technology which now constitute the slave of man - if man is not enslaved by it.

(Venus in Sagittarius. Uranus in Aquarius)The worst tragedy that could have befallen me was my success. I knew right away that I was through - cast out.

"There is no such thing as failure. Only giving up too soon.

When I worked on the polio vaccine, I had a theory. I guided each [experiment] by imagining myself in the phenomenon in which I was interested. The intuitive realm . . . the realm of the imagination guides my thinking.

The evolvers are people who cause things to change. The maintainers of the status quo do everything to keep things from changing. And, there I see differences of perception. Differences in vision. Differences in interpretation, and differences in temperament, in personality. The number of evolvers are much fewer than the maintainers of the status quo. And amongst the evolvers, there are some who are initiators, some who go along with what other people recognize to be new or different.

I have come to associate a kind of success that we are referring to, to individuals who have a combination of attributes that are often associated with creativity. In a way they are mutants, they are different from others. And they follow their own drummer. We know what that means. And are we all like that? We are not like that. If you are, then it would be well to recognize that there were others before you. And, people like that are not very happy or content, until they are allowed to express, or they can express what's in them to express.

Reason alone will not serve. Intuition alone can be improved by reason, but reason alone without intuition can easily lead the wrong way. They both are necessary. The way I like to put it is that when I have an intuition about something, I send it over to the reason department. Then after I've checked it out in the reason department, I send it back to the intuition department to make sure that it's still all right. That's how my mind works, and that's how I work. That's why I think that there is both an art and a science to what we do. The art of science is as important as so-called technical science. You need both. It's this combination that must be recognized and acknowledged and valued.

If humankind would accept and acknowledge this responsibility and become creatively engaged in the process of evolution, consciously as well as unconsciously, a new reality would emerge, and a new age could be born.

"If all the insects on earth disappeared, within 50 years all life on earth would disappear. If all humans disappeared, within 50 years all species would flourish as never before."

Jonas Salk

Born October 28, 1914

New York City, New York, USA

Died June 23, 1995

La Jolla, California, USA

Residence USA

Religion Humanist[citation needed]Jonas Edward Salk (October 28, 1914 – June 23, 1995) was an American physician and researcher, best known for the development of the first polio vaccine (the eponymous Salk vaccine).

During his life he worked in New York, Michigan, Pittsburgh and California. In his later career, Salk devoted much energy toward the development of an AIDS vaccine.

Salk did not seek wealth or fame through his innovations, famously stating, "Who owns my polio vaccine? The people! Could you patent the sun?"

Jonas E. Salk was born in New York City to a family of poor Russian-Jewish immigrants, Dora and Daniel B. Salk. He graduated from Townsend Harris High School and then went to the City College of New York with a B.Sc., and then received his medical degree from the College of Medicine at New York University in June 1939.

While at college he met his future wife, Donna Lindsay Calfin, whom he married on June 9, 1939. They had three children: Peter, Darrell, and Jonathan. In 1968, they divorced, and in 1970 Salk married Françoise Gilot, the former mistress of Pablo Picasso.

After graduating, Salk first worked as a staff physician at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. In 1947, he moved to Pittsburgh, where he led the Virus Research lab at the University of Pittsburgh. During the 1950s, he developed, tested, and refined the first successful polio vaccine. In 1955 he began immunizations at Pittsburgh's Arsenal Elementary School in the Lawrenceville neighborhood and made international news as the man who beat polio.

In 1962, Salk struck out on his own, leaving the University of Pittsburgh and establishing the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California, where the major focus of study was molecular biology and genetics. The first faculty included many distinguished members such as Jacob Bronowski and Francis Crick.

Jonas Salk directed the institute until his retirement in 1985. Salk died in La Jolla at the age of 80.

During his life, he received many awards and honours: The Lasker Award (1956), The Bruce Memorial Award (1958), The Jawaharlal Nehru Award (1975), Congressional Gold Medal of Honor and Presidential Medal of Freedom (1977).

As a child, Salk did not show any interest in medicine or science in general. He says in an interview with the Academy of Achievement:

As a child I was not interested in science. I was merely interested in things human, the human side of nature, if you like, and I continue to be interested in that. That's what motivates me. And in a way, it's the human dimension that has intrigued me.

His first desire was to become a lawyer and only due to his mother's persuasion (which included her telling him he wouldn’t be good at it), he changed from a pre-law student to a pre-med student. During his first year in medical school, he was offered the chance to do research and teach biochemistry. He recalls this experience in the previously mentioned interview:At one point at the end of my first year of medical school, I received an opportunity to spend a year in research and teaching in biochemistry, which I did. And at the end of that year, I was told I could, if I wished, switch and get a Ph.D. in biochemistry but my preference was to stay with medicine. And I believe that this is all linked to my original ambition, or desire, which was to be of some help to humankind, so to speak, in a larger sense than just on a one-to-one basis.

While attending NY Medical College, he heard two lectures that would change his life forever. Salk reflected on the lectures in 1990:In the first lecture, we were told that it was possible to immunize against diphtheria and tetanus by the use of a chemically treated toxin [to kill it]... In the very next lecture, we were told that in order to immunize against a virus disease it was necessary to go through the experience of infection. It was not possible to kill the virus... The light went on at that point. I said that those two statements can’t possibly both be true. One has to be false.

In 1938, while still at the college, Salk began working with Dr. Thomas Francis, Jr. on an influenza vaccine. In 1941, Francis was appointed the head of the epidemiology department at the newly formed School of Public Health at the University of Michigan, and Salk, who in 1942 won a research fellowship, followed him. Together they worked to develop an influenza vaccine at the behest of the U.S. Army. Salk advanced to the position of assistant professor of epidemiology and continued his work on virology.In 1947, Salk received a position at the University of Pittsburgh, as the head of the Virus Research lab. Though he continued his research on improving the influenza vaccine, he set his sights on the Poliomyelitis virus. The poliovirus initially attacks the nervous system and within a few hours of infection, paralysis can occur. The death rate of the disease is about 5-10%. Death usually occurs when the breathing muscles become paralyzed. Polio was sometimes hard to diagnose because of its flu-like symptoms, which include stiff neck, fever, and headache.

At that time, it was believed that immunity can come only after the body has survived at least a mild infection by live virus. In contrast, Salk observed that it is possible to acquire immunity through contact with inactivated (killed) virus. Using formaldehyde, Salk killed the poliovirus, but kept it intact enough to trigger the necessary immune response. Salk's research caught the attention of Basil O'Connor, president of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (now known as the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation). The organization decided to fund Salk's efforts to develop a killed virus vaccine.

The vaccine was first tested in monkeys, and then in patients at the D.T. Watson Home for Crippled Children. After successful tests, in 1952, Salk tested his vaccine on volunteering parties, including himself, the laboratory staff, his wife, and his children. In 1954, national testing began on two million children, ages six to nine, who became known as the Polio Pioneers. This was one of the first double-blind placebo-controlled tests, which has since become standard: half of the treated received the vaccine, and half received a placebo, where neither the individuals nor the researchers know who belongs to the control group and the experimental group. One-third of the children, who lived in areas where vaccine was not available, were observed in order to evaluate the background level of polio in this age group. On April 12, 1955, the results were announced: the vaccine was safe and effective. The patient would develop immunity to the live disease due to the body's earlier reaction to the killed virus.

Salk's vaccine was instrumental in the near eradication of a once widely-feared disease. Polio’s outbreak in 1916 left 6000 dead and 27,000 paralyzed. In 1952, 57,628 cases were recorded. After the vaccine became available, polio cases in the U.S. dropped by 85-90 percent in only two years. The last indigenous case of polio in the U.S. was reported in 1991.

Dr. Salk's last years were spent searching for a vaccine against AIDS. According to the March of Dimes, Dr. Salk informed them that he had developed a vaccination for the disease that was still in the testing stages. He administered this to his son, Peter, as he had with the Polio vaccine. Merck & Co., Inc. later purchased the experimental antibody.

Jonas Salk died on June 23, 1995. He was 80 years old at the time of his death.

Controversy

Only one member of the team that developed the Polio vaccine is still alive: Julius S. Youngner, a microbiologist who has spent 56 years working at The University of Pittsburgh.Youngner said he felt insulted and betrayed when Salk did not acknowledge his lab colleagues during his famous speech at the University of Michigan on April 12, 1955. That was the day the world learned the polio vaccine worked. Salk thanked everyone but his own team.

Renowned scientist Roger Revelle felt animosity toward Salk even years after the Salk Institute received a prime piece of San Diego real estate that Revelle felt should have gone to the fledgling University of California, San Diego campus. "Jonas decided that he wanted the best piece of land that we had," Revelle said in 1985. "Of course, it was much more important to get Salk here than to get the University here. He is a folk hero, even though he is... not very bright."

Developer of Polio Vaccine

Jonas Salk Date of birth: October 28, 1914

Date of death: June 23, 1995In America in the 1950s, summertime was a time of fear and anxiety for many parents; this was the season when children by the thousands became infected with the crippling disease poliomyelitis, or polio. This burden of fear was lifted forever when it was announced that Dr. Jonas Salk had developed a vaccine against the disease. Salk became world-famous overnight, but his discovery was the result of many years of painstaking research.

was born in New York City. His parents were Russian-Jewish immigrants who, although they themselves lacked formal education, were determined to see their children succeed, and encouraged them to study hard. Jonas Salk was the first member of his family to go to college. He entered the City College of New York intending to study law, but soon became intrigued by medical science.

While attending medical school at New York University, Salk was invited to spend a year researching influenza. The virus that causes flu had only recently been discovered and the young Salk was eager to learn if the virus could be deprived of its ability to infect, while still giving immunity to the illness. Salk succeeded in this attempt, which became the basis of his later work on polio.

After completing medical school and his internship, Salk returned to the study of influenza, the flu virus. World War II had begun, and public health experts feared a replay of the flu epidemic that had killed millions in the wake of the First World War. The development of vaccines controlled the spread of flu after the war and the epidemic of 1919 did not recur.

In 1947, Salk accepted an appointment to the University of Pittsburgh Medical School. While working there, with he National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, Salk saw an opportunity to develop a vaccine against polio, and devoted himself to this work for the next eight years.

In 1955 Salk's years of research paid off. Human trials of the polio vaccine effectively protected the subject from the polio virus. When news of the discovery was made public on April 12, 1955, Salk was hailed as a miracle worker. He further endeared himself to the public by refusing to patent the vaccine. He had no desire to profit personally from the discovery, but merely wished to see the vaccine disseminated as widely as possible.

Salk's vaccine was composed of "killed" polio virus, which retained the ability to immunize without running the risk of infecting the patient. A few years later, a vaccine made from live polio virus was developed, which could be administered orally, while Salk's vaccine required injection. Further, there was some evidence that the "killed" vaccine failed to completely immunize the patient. In the U.S., public health authorities elected to distribute the "live" oral vaccine instead of Salk's. Tragically, the preparation of live virus infected some patients with the disease, rather than immunizing them. Since the introduction of the original vaccine, the few new cases of polio reported in the United States were probably caused by the "live" vaccine which was intended to prevent them.

In countries where Salk's vaccine has remained in use, the disease has been virtually eradicated.

In 1963, Salk founded the Jonas Salk Institute for Biological Studies, an innovative center for medical and scientific research. Jonas Salk continued to conduct research and publish books, some written in collaboration with one or more of his sons, who are also medical scientists.

Salk's published books include Man Unfolding (1972), The Survival of the Wisest (1973), World Population and Human Values: A New Reality (1981), and Anatomy of Reality (1983).

Dr. Salk's last years were spent searching for a vaccine against AIDS. Jonas Salk died on June 23, 1995. He was 80 years old.