Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

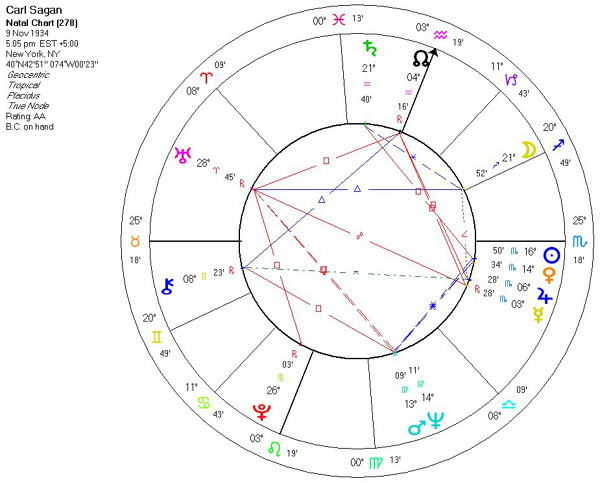

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

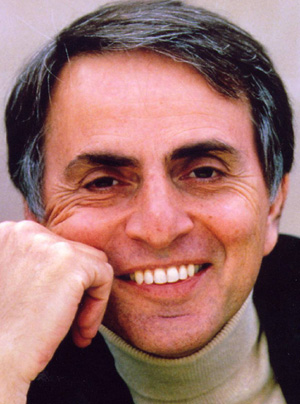

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

A celibate clergy is an especially good idea, because it tends to suppress any hereditary propensity toward fanaticism.

A central lesson of science is that to understand complex issues (or even simple ones), we must try to free our minds of dogma and to guarantee the freedom to publish, to contradict, and to experiment. Arguments from authority are unacceptable.

(Saturn in Aquarius square Sun in Scorpio)All of the books in the world contain no more information than is broadcast as video in a single large American city in a single year. Not all bits have equal value.

But the fact that some geniuses were laughed at does not imply that all who are laughed at are geniuses. They laughed at Columbus, they laughed at Fulton, they laughed at the Wright Brothers. But they also laughed at Bozo the Clown.

For me, it is far better to grasp the Universe as it really is than to persist in delusion, however satisfying and reassuring.

(Sun, Venus, Jupiter & Mercury in Scorpio)For small creatures such as we the vastness is bearable only through love.

(Venus conjunct Sun. Taurus Ascendant.)I am often amazed at how much more capability and enthusiasm for science there is among elementary school youngsters than among college students.

I can find in my undergraduate classes, bright students who do not know that the stars rise and set at night, or even that the Sun is a star.

I worry that, especially as the Millennium edges nearer, pseudo-science and superstition will seem year by year more tempting, the siren song of unreason more sonorous and attractive.

If we long to believe that the stars rise and set for us, that we are the reason there is a Universe, does science do us a disservice in deflating our conceits?

Imagination will often carry us to worlds that never were. But without it we go nowhere.

(Neptune conjunct Mars in Virgo)Our species needs, and deserves, a citizenry with minds wide awake and a basic understanding of how the world works.

Personally, I would be delighted if there were a life after death, especially if it permitted me to continue to learn about this world and others, if it gave me a chance to discover how history turns out.

Science is a way of thinking much more than it is a body of knowledge.

Skeptical scrutiny is the means, in both science and religion, by which deep thoughts can be winnowed from deep nonsense.

Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known.

The brain is like a muscle. When it is in use we feel very good. Understanding is joyous.

The universe is not required to be in perfect harmony with human ambition.

The universe seems neither benign nor hostile, merely indifferent.

Think of how many religions attempt to validate themselves with prophecy. Think of how many people rely on these prophecies, however vague, however unfulfilled, to support or prop up their beliefs. Yet has there ever been a religion with the prophetic accuracy and reliability of science?

We have also arranged things so that almost no one understands science and technology. This is a prescription for disaster. We might get away with it for a while, but sooner or later this combustible mixture of ignorance and power is going to blow up in our faces.

(Uranus square Pluto)We live in a society exquisitely dependent on science and technology, in which hardly anyone knows anything about science and technology.

We've arranged a civilization in which most crucial elements profoundly depend on science and technology.

When you make the finding yourself - even if you're the last person on Earth to see the light - you'll never forget it.

Who are we? We find that we live on an insignificant planet of a humdrum star lost in a galaxy tucked away in some forgotten corner of a universe in which there are far more galaxies than people.

Widespread intellectual and moral docility may be convenient for leaders in the short term, but it is suicidal for nations in the long term. One of the criteria for national leadership should therefore be a talent for understanding, encouraging, and making constructive use of vigorous criticism.

A religion old or new, that stressed the magnificence of the universe as revealed by modern science, might be able to draw forth reserves of reverence and awe hardly tapped by the conventional faiths. Sooner or later, such a religion will emerge.

(Discussing the possibilities of extraterrestrial life)

I would love it even if they were short, sullen, grumpy and sexually obsessed. But there just isn't any good evidence.My deeply held belief is that if a god of anything like the traditional sort exists, our curiosity and intelligence is provided by such a God. We would be unappreciative of that gift . . . if we suppressed our passion to explore the universe and ourselves.

Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality.

Each of us is a tiny being, permitted to ride on the outermost skin of one of the smaller planets for a few dozen trips around the local star.

The fact that someone says something, doesn't mean it's true. Doesn't mean they're lying, but it doesn't mean it's true.

“Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

“You have to know the past to understand the present.”

“We are star-stuff”

“We are the product of 4.5 billion years of fortuitous, slow biological evolution. There is no reason to think that the evolutionary process has stopped. Man is a transitional animal. He is not the climax of creation.”

Goddard represented a unique combination of visionary dedication and technological brilliance. He studied physics because he needed physics to get to Mars. In reading the notebooks of Robert Goddard, I am struck by how powerful his exploratory and scientific motivations were – and how influental speculative ideas, even erroneous ones, can be on the shaping of the future.

Source: Broca's Brain“We are like butterflies who flutter for a day and think its forever.”

“There are many hypotheses in science which are wrong. That's perfectly all right; they're the aperture to finding out what's right. Science is a self-correcting process. To be accepted, new ideas must survive the most rigorous standards of evidence and scrutiny.”

“We are a way for the cosmos to know itself”

In science it often happens that scientists say, "You know, that's a really good argument, my position is mistaken," and then they actually change their minds, and you never hear that old view from them again. They really do it. It doesn't happen as often as it should, because scientists are human and change is sometimes painful. But it happens every day. I cannot recall the last time something like that happened in politics or religion.

All of us cherish our beliefs. They are, to a degree, self-defining. When someone comes along who challenges our belief system as insufficiently well-based -- or who, like Socrates, merely asks embarrassing questions that we haven't thought of, or demonstrates that we've swept key underlying assumptions under the rug -- it becomes much more than a search for knowledge. It feels like a personal assault., The Demon-Haunted World

The visions we offer our children shape the future. It matters what those visions are. Often they become self-fulfilling prophecies. Dreams are maps.

"Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence."

“For the first time, we have the power to decide the fate of our planet and ourselves, ... This is a time of great danger, but our species is young, and curious, and brave. It shows much promise.”

“In our time, we have sifted the sands of Mars, we have established a presence there, we have fulfilled a century of dreams!”

“The significance of a finding that there are other beings who share this universe with us would be absolutely phenomenal, it would be an epochal event in human history.”

“What's the harm of a little mystification? It sure beats boring statistical analyses.”

(Neptune conjunct Mars)“We live at a moment when our relationships to each other, and to all other beings with whom we share this planet, are up for grabs.”

“We have swept through all of the planets in the solar system, from Mercury to Neptune, in a historic 20 (to) 30 year age of spacecraft discovery…”

“Are we an exceptionally unlikely accident or is the universe brimming over with intelligence? (It's) a vital question for understanding ourselves and our history…”

I maintain there is much more wonder in science than in pseudoscience. And in addition, to whatever measure this term has any meaning, science has the additional virtue, and it is not an inconsiderable one, of being true.

In every country, we should be teaching our children the scientific method and the reasons for a Bill of Rights. With it comes a certain decency, humility and community spirit. In the demon-haunted world that we inhabit by virtue of being human, this may be all that stands between us and the enveloping darkness.

(North Node in Aquarius)It is of interest to note that while some dolphins are reported to have learned English -- up to fifty words used in correct context -- no human being has been reported to have learned dolphinese.

One glance at a book and you hear the voice of another person, perhaps someone dead for 1,000 years. To read is to voyage through time.

Carl Sagan

Born November 9, 1934

Brooklyn, New York

Died December 20, 1996

Seattle, WashingtonCarl Edward Sagan (November 9, 1934 – December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer and astrobiologist and a highly successful popularizer of astronomy, astrophysics and other natural sciences. He pioneered exobiology and promoted the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI). He is world-famous for writing popular science books and for co-writing and presenting the award-winning 1980 television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, which has been seen by more than 600 million people in over 60 countries, making it the most widely watched PBS program in history.[1] A book to accompany the program was also published. He also wrote the novel Contact, the basis for the 1997 Robert Zemeckis film of the same name starring Jodie Foster. During his lifetime, Sagan published more than 600 scientific papers and popular articles and was author, co-author, or editor of more than 20 books. In his works, he frequently advocated skeptical inquiry, humanism, and the scientific method.

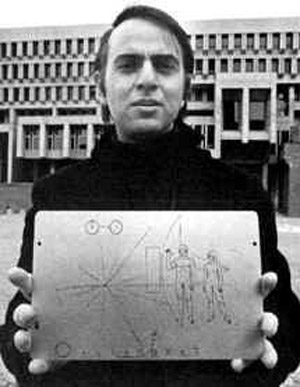

Sagan of Astronomy Department, Cornell University, 1969Carl Sagan was born in Brooklyn, New York.[2] His parents were Jewish; his father, Sam Sagan, was a garment worker and his mother, Rachel Molly Gruber, was a housewife. Carl was named in honor of Rachel's biological mother, Chaiya/ Clara, "the mother she never knew", in Sagan's words. Sagan graduated from Rahway (NJ) High School in 1951.[3] He attended the University of Chicago, where he received a bachelor's degree (1955) and a master's degree (1956) in physics, before earning his doctorate (1960) in astronomy and astrophysics. During his time as an undergraduate, Sagan spent some time working in the laboratory of the geneticist H. J. Muller. From 1962 to 1968, he worked at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Sagan taught at Harvard University until 1968, when he moved to Cornell University. He became a full professor at Cornell in 1971 and directed the Laboratory for Planetary Studies there. From 1972 to 1981 he was Associate Director of the Center for Radio Physics and Space Research at Cornell.

Sagan was a leader in the U.S. space program since its inception and worked as an adviser to NASA since the 1950s. (One of his many duties during his tenure at the space agency included briefing the Apollo astronauts before their flights to the Moon.) Sagan contributed to most of the unmanned missions that explored the solar system, placing experiments on many robotic space expeditions. He conceived the idea of adding an unalterable and universal message on spacecraft destined to leave the solar system that could be understood by any extraterrestrial intelligence that might find it. Sagan assembled the first physical message that was sent into space: a gold-anodized plaque, attached to the space probe Pioneer 10, launched in 1972. Pioneer 11, also containing the plaque, was launched the following year. He continued to refine his designs and the most elaborate such message he helped to develop and assemble was the Voyager Golden Record that was sent out with the Voyager space probes in 1977.

Sagan taught at Cornell a course on critical thinking until his death in 1996 from a rare bone marrow disease. The course had only a limited number of seats, although hundreds of students tried to attend. He chose about 20 students who were allowed to enroll by reading huge piles of application essays. The course was discontinued after his death.

Scientific achievements

A still from CosmosSagan was central to the discovery of the high surface temperatures of the planet Venus. In the early 1960s, no one knew for certain the basic conditions of Venus' surface and Sagan listed the possibilities in a report (which were later depicted for popularization in a Time-Life book, Planets) — his own view was that the planet was dry and very hot, as opposed to the balmy paradise others had imagined. He had investigated radio emissions from Venus and concluded that there was a surface temperature of 500°C (900°F). As a visiting scientist to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, he contributed to the first Mariner missions to Venus, working on the design and management of the project. Mariner 2 confirmed his views on the conditions of Venus in 1962.Sagan was among the first to hypothesize that Saturn's moon Titan[4] and Jupiter's moon Europa may possess oceans (a subsurface ocean, in the case of Europa) or lakes, thus making the hypothesized water ocean on Europa potentially habitable for life. Europa's subsurface ocean was later indirectly confirmed by the spacecraft Galileo. Sagan also helped solve the mystery of the reddish haze seen on Titan, revealing that it is composed of complex organic molecules constantly raining down to the moon's surface.

He furthered insights regarding the atmospheres of Venus and Jupiter as well as seasonal changes on Mars. Sagan established that the atmosphere of Venus is extremely hot and dense with crushing pressures. He also perceived global warming as a growing, man-made danger and likened it to the natural development of Venus into a hot, life-hostile planet through greenhouse gases. Sagan speculated (along with his Cornell colleague Edwin Ernest Salpeter) about life in Jupiter's clouds, given the planet's dense atmospheric composition rich in organic molecules. He studied the observed color variations on Mars’ surface, concluding that they were not seasonal or vegetation changes as most believed, but shifts in surface dust caused by windstorms.

Sagan is best known, however, for his research on the possibilities of extraterrestrial life, including experimental demonstration of the production of amino acids from basic chemicals by radiation.[5]

Scientific advocacy

Planetary Society members at the organization's founding. Carl Sagan is seated to the right.Sagan was a proponent of the search for extraterrestrial life. He urged the scientific community to listen with radio telescopes for signals from intelligent extraterrestrial lifeforms. So persuasive was he that by 1982, he was able to get a petition advocating SETI published in the journal Science, signed by 70 scientists, including seven Nobel Prize winners. This was a tremendous turnaround in the respectability of this controversial field. Sagan also helped Dr. Frank Drake write the Arecibo message, a radio message beamed into space from the Arecibo radio telescope on November 16, 1974, aimed at informing extraterrestrials about Earth.CETI conference, 1972He was editor-in-chief of Icarus (a professional journal concerning planetary research) for 12 years. He co-founded the Planetary Society, the largest space-interest group in the world, with over 100,000 members in more than 140 countries, and was a member of the SETI Institute Board of Trustees. Sagan served as Chairman of the Division for Planetary Science of the American Astronomical Society, as President of the Planetology Section of the American Geophysical Union, and as Chairman of the Astronomy Section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

At the height of the Cold War, Sagan became involved in public awareness efforts for the effects of nuclear war when a mathematical climate model suggested that a substantial nuclear exchange could upset the delicate balance of life on Earth. He was the last of five authors — the "S" of the "TTAPS" report as the research paper came to be known. He eventually co-authored the scientific paper that predicted nuclear winter[6] would follow nuclear war. He also co-authored the book A Path Where No Man Thought: Nuclear Winter and the End of the Arms Race, a comprehensive examination of the phenomenon of nuclear winter.

Sagan famously predicted on ABC's Nightline in 1991 that smoky oil fires in Kuwait (set by Saddam Hussein's army during the first Gulf War) would cause a worldwide ecological disaster of black clouds resulting in global cooling. Retired atmospheric physicist and climate change skeptic Fred Singer dismissed Sagan's prediction as nonsense, predicting that the smoke would dissipate in a matter of days. In his book The Demon-Haunted World (see below), Sagan gave a list of errors he had made (including his predictions about the effects of the Kuwaiti oil fires) as an example of how science is tentative, a self-correcting process.

Sagan is also known for being involved as a researcher in Project A119, a secret US Air Force operation whose purpose was to explode an atomic bomb on Earth's Moon.

Social concerns

Sagan believed that the Drake equation suggested that a large number of extraterrestrial civilizations would form, but that the lack of evidence of such civilizations (the Fermi paradox) suggests that technological civilizations tend to destroy themselves rather quickly. This stimulated his interest in identifying and publicizing ways that humanity could destroy itself, with the hope of avoiding such a cataclysm and eventually becoming a spacefaring species.

Sagan in the early 1970sSagan's deep concern regarding the potential destruction of human civilization in a nuclear holocaust had been conveyed in a memorable cinematic sequence in the final episode of Cosmos, called "Who Speaks for Earth?". Following his marriage to novelist Ann Druyan (his third wife) in June 1981, Sagan became more politically active — particularly in regard to the escalation of the nuclear arms race under President Ronald Reagan.In March 1983, hoping to blunt the momentum of the nuclear freeze movement, Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative — a multi-billion dollar project to develop a comprehensive defense against attack by nuclear missiles, which was quickly dubbed the "Star Wars" program. Sagan spoke out against the project, arguing that it was technically impossible to develop a system with the level of perfection required, and far more expensive to build than for an enemy to defeat through decoys and other means — and that its construction would seriously destabilize the nuclear balance between the United States and the Soviet Union, making further progress toward nuclear disarmament impossible.

When Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev declared a unilateral moratorium on the testing of nuclear weapons, which would begin on August 6, 1985 — the 40th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima — the Reagan administration dismissed the dramatic move as nothing more than propaganda, and refused to follow suit. In response, American anti-nuclear and peace activists staged a series of protest actions at the Nevada Test Site, beginning on Easter Sunday of 1986 and continuing through 1987. Hundreds of people (including such notable figures as Daniel Ellsberg and Martin Sheen) engaged in acts of civil disobedience and were arrested. Carl Sagan, who had been arrested for participating in an anti-war protest during the Vietnam War, was himself arrested on two separate occasions as he climbed over a chain-link fence at the Test Site.

Carl Sagan was an avid user of marijuana, although he never admitted this publicly during his life. Under the pseudonym "Mr. X", he wrote an essay concerning cannabis smoking in the 1971 book Marihuana Reconsidered, whose editor was Lester Grinspoon.[7] In his essay, Sagan commented that marijuana encouraged some of his works and enhanced experiences. After Sagan's death, Grinspoon disclosed this to Sagan's biographer, Keay Davidson. When the biography, entitled Carl Sagan: A Life, was published in 1999, the marijuana exposure stirred some media attention.[8][9][10]

Popularization of science

Sagan in 1980Sagan's capability to convey his ideas allowed many people to better understand the cosmos. He delivered the 1977/1978 Christmas Lectures for Young People at the Royal Institution. He hosted and, with Ann Druyan, co-wrote and co-produced the highly popular thirteen-part PBS television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage (modeled on Jacob Bronowski's The Ascent of Man).Sagan with a model of the Viking Lander probes which would land on Mars. Sagan examined possible landing sites for Viking along with Mike Carr and Hal Masursky.Cosmos covered a wide range of scientific subjects including the origin of life and a perspective of our place in the universe. The series was first broadcast by the Public Broadcasting Service in 1980. It won an Emmy and a Peabody Award; according to the NASA Office of Space Science, it has been since broadcast in more than 60 countries and seen by over 600 million people.

Sagan also wrote books to popularize science, such as Cosmos, which reflected and expanded upon some of the themes of A Personal Voyage, and became the best-selling science book ever published in English,[11] The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence, which won a Pulitzer Prize, and Broca's Brain: Reflections on the Romance of Science. Sagan also wrote the best-selling science fiction novel Contact, but did not live to see the book's 1997 motion picture adaptation, which starred Jodie Foster and won the 1998 Hugo Award.

From Cosmos and his frequent appearances on The Tonight Show, Sagan became associated with the catch phrase "billions and billions." (He never actually used that phrase in Cosmos,[12] but his distinctive delivery and frequent use of billions (with noted emphasis on the opening "b") made this a favorite phrase of Johnny Carson, Gary Kroeger, Mike Myers, Bronson Pinchot, Harry Shearer and others, doing many affectionate impressions of him. Sagan took this in good humor, and his final book was entitled Billions and Billions (see below) and opened with a tongue-in-cheek discussion of this catch phrase.) A humorous unit of measurement, the Sagan, has now been coined to stand for any count of at least 4,000,000,000.

He wrote a sequel to Cosmos, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space, which was selected as a notable book of 1995 by The New York Times. He appeared on PBS' Charlie Rose program in January 1995. (video) Carl Sagan also wrote an introduction for the bestselling book by Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time.

Sagan presents a speculation concerning the origin of the swastika symbol in his book, Comet. Sagan hypothesized that a comet approached so close to Earth in antiquity that the jets of gas streaming out of it were visible, bent by the comet's rotation. The book Comet reproduces an ancient Chinese manuscript that shows comet tail varieties; most are variations on simple comet tails, but the last shows the comet nucleus with four bent arms extending from it, showing a swastika.

Sagan caused mixed reactions among other professional scientists. On the one hand, there was general support for his popularization of science, his efforts to increase scientific understanding among the general public, and his positions in favor of scientific skepticism and against pseudoscience; most notably his thorough debunking of the book Worlds in Collision by Immanuel Velikovsky. On the other hand, there was some unease that the public would misunderstand some of the personal positions and interests that Sagan took as being part of the scientific consensus. Sagan's arguments against Velikovsky's catastrophism have been criticized by some of his colleagues. Robert Jastrow of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies wrote: "Professor Sagan's calculations, in effect, ignore the law of gravity. Here, Dr. Velikovsky was the better astronomer."

Late in his life, Sagan's books developed his skeptical, naturalistic view of the world. In The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, he presented tools for testing arguments and detecting fallacious or fraudulent ones, essentially advocating wide use of critical thinking and the scientific method. The compilation, Billions and Billions: Thoughts on Life and Death at the Brink of the Millennium, published in 1997 after Sagan's death, contains essays written by Sagan, such as his views on abortion, and his widow Ann Druyan's account of his death as a skeptic, agnostic, and freethinker.

In 2006, Ann Druyan edited Sagan's 1985 Gifford Lectures in Natural Theology into a new book, The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God, in which he elaborates on his views of divinity in the natural world.

Personality

In 1966, Sagan was asked to contribute an interview about the possibility of extraterrestrials to a proposed introduction to the film 2001: A Space Odyssey. According to an unsourced anecdote in The Independent, Sagan "responded by saying that he wanted editorial control and a percentage of the film's takings, which was rejected."[13]In 1994, Apple Computer began developing the Power Macintosh 7100. They chose the internal code name "Carl Sagan", the in-joke being that the mid-range PowerMac 7100 would make Apple "billions and billions."[14] Though the project name was strictly internal and never used in public marketing, when Sagan learned of this internal usage he sued Apple Computer to use a different project name. Other models released conjointly had code names such as "Cold fusion" and "Piltdown Man", and he was displeased at being associated with what he considered pseudoscience. Though Sagan lost the suit, Apple engineers complied with his demands anyway, renaming the project "BHA" (for Butt-Head Astronomer).[citation needed] Sagan promptly sued Apple for libel over the new name, claiming that it subjected him to contempt and ridicule, but lost this lawsuit as well. Still, the 7100 saw another name change: it was finally referred to internally as "LAW" (Lawyers Are Wimps).

Sagan with DruyanSagan wrote frequently about religion and the relationship between religion and science, expressing his skepticism about many conventional conceptualizations of God. Sagan once stated, for instance, that "The idea that God is an oversized white male with a flowing beard, who sits in the sky and tallies the fall of every sparrow is ludicrous. But if by 'God,' one means the set of physical laws that govern the universe, then clearly there is such a God. This God is emotionally unsatisfying... it does not make much sense to pray to the law of gravity."[15] Sagan is also widely regarded as a freethinker or skeptic; one of his most famous quotations (as seen in Cosmos) was "Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence." (This was actually based on a nearly identical earlier quote by fellow CSICOP founder Marcello Truzzi, "Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof."[16] The quote is also known, under different wording, as the principle of Laplace — attributed to Pierre-Simon Marquis de Laplace (March 23, 1749 – March 5, 1827), a French mathematician and astronomer: "The weight of evidence for an extraordinary claim must be proportioned to its strangeness.")

Sagan married three times: the famous biologist Lynn Margulis (mother of Dorion Sagan and Jeremy Sagan) in 1957; artist Linda Salzman (mother of Nick Sagan) in 1968; and author Ann Druyan (mother of Sasha and Sam) in 1981, to whom he remained married until his death in 1996.

Isaac Asimov described Sagan as one of the only two people he ever met who were just plain smarter than Asimov himself. The other was computer scientist and expert on artificial intelligence, Marvin Minsky.

Sagan and UFOs

Sagan had some interest in UFO reports from at least 1964, when he had several conversations on the subject with Jacques Vallee (Westrum 37). Though quite skeptical of any extraordinary answer to the UFO question, Sagan thought that science should study the phenomenon, at least because there was widespread public interest in UFO reports.Stuart Appelle notes that Sagan "wrote frequently on what he perceived as the logical and empirical fallacies regarding UFOs and the abduction experience. Sagan rejected an extraterrestrial explanation for the phenomenon but felt there were both empirical and pedagogical benefits for examining UFO reports and that the subject was, therefore, a legitimate topic of study" (Appelle 22).

In 1966, Sagan was a member of the Ad Hoc Committee to Review Project Blue Book. The committee concluded that the U.S. Air Force's Project Blue Book had been lacking as a scientific study, and recommended a university-based project to give the UFO phenomenon closer scientific scrutiny. The Condon Committee (1966-1968), led by physicist Edward Condon, and their still-controversial final report, formally concluded that there was nothing anomalous about UFO reports.

Ron Westrum writes that "The high point of Sagan's treatment of the UFO question was the AAAS's symposium in 1969. A wide range of educated opinions on the subject were offered by participants, including not only proponents as James McDonald and J. Allen Hynek but also skeptics like astronomers William Hartmann and Donald Menzel. The roster of speakers was balanced, and it is to Sagan's credit that this event was presented in spite of pressure from Edward Condon" (Westrum 37-38). With physicist Thornton Page, Sagan edited the lectures and discussions given at the symposium; these were published in 1972 as UFO's: A Scientific Debate. Jerome Clark writes that Sagan's perspective on UFO's irked Condon: "... though a skeptic, [Sagan] was too soft on UFOs for Condon's taste. In 1971, he considered blackballing Sagan from the prestigious Cosmos Club" (Clark 603).

Some of Sagan's many books examine UFOs (as did one episode of Cosmos) and he recognized a religious undercurrent to the phenomenon. However, Westrum writes that "Sagan spent very little time researching UFOs ... he thought that little evidence existed to show that the UFO phenomenon represented alien spacecraft and that the motivation for interpreting UFO observations as spacecraft was emotional" (Westrum 37).

It is sometimes noted that Sagan's generally skeptical attitude to UFOs conflicted sharply with his views in a 1966 book he wrote with Russian astronomer and astrophysicist I.S. Shklovskii, Intelligent Life in the Universe. Here Sagan instead argued that technologically advanced alien civilizations were common and he considered it very probable that Earth had been visited many times in the past. Yet only a few years later in UFO's: A Scientific Debate, Sagan was now highly skeptical of interstellar visitation. As to the physical possibility of interstellar travel, Sagan brought up the proposed Bussard ramjet as an interstellar vehicle. While not terribly practical, Sagan thought such proposed propulsion systems were nevertheless important because they demonstrated that there were conceivable ways of accomplishing interstellar travel "without bumping into fundamental physical constraints. And this suggests that it is premature to say that interstellar space flight is out of the question." But to this Sagan added, "I believe the numbers work out in such a way that UFO's as interstellar vehicles is extremely unlikely, but I think it is an equally bad mistake to say that interstellar space flight is impossible."

Sagan again revealed his views on interstellar travel in his 1980 Cosmos series. He rejected the idea that UFOs are visiting Earth, maintaining that the chances any alien spacecraft would visit the Earth are vanishingly small. However, in another episode he said the stars would "beckon" to humanity, and described the Bussard ramjet as one way humans might achieve interstellar travel. In one of his last written works, Sagan again claimed that there was no evidence that aliens have actually visited the Earth, either in the past or present (Sagan, 1996: 81-96, 99-104).

Death and legacy

Sagan in 1996, shortly before his deathAfter a long and difficult fight with myelodysplasia, Sagan died of pneumonia at the age of 62 on December 20, 1996, at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington. Sagan was a significant figure, and his supporters credit his importance to his popularization of the natural sciences, opposing both restraints on science and reactionary applications of science, defending democratic traditions, resisting nationalism, defending humanism, and arguing against geocentric and anthropocentric views.The landing site of the unmanned Mars Pathfinder spacecraft was renamed the Carl Sagan Memorial Station on July 5, 1997. Asteroid 2709 Sagan is also named in his honor.

The 1997 movie Contact (see above), based on Sagan's novel of the same name and finished after his death, ends with the dedication "For Carl."

On November 9, 2001, on what would have been Sagan’s 67th birthday, the NASA Ames Research Center dedicated the site for the Carl Sagan Center for the Study of Life in the Cosmos. "Carl was an incredible visionary, and now his legacy can be preserved and advanced by a 21st century research and education laboratory committed to enhancing our understanding of life in the universe and furthering the cause of space exploration for all time", said NASA Administrator Daniel Goldin. Ann Druyan was at the center as it opened its doors on October 22, 2006.

Sagan's son, Nick Sagan, wrote several episodes in the Star Trek franchise. In an episode of Star Trek: Enterprise entitled "Terra Prime", a quick shot is shown of the relic rover Sojourner, part of the Mars Pathfinder mission, placed by a historical marker at Carl Sagan Memorial Station on the Martian surface. The marker displays a quote from Sagan: "Whatever the reason you're on Mars, I'm glad you're there, and I wish I was with you."

Sagan's student, Steve Squyres, would lead the team that landed the Spirit Rover and Opportunity Rover successfully on Mars in 2004.

Carl Edward Sagan was born Nov. 9, 1934, in Brooklyn, N.Y. At Cornell since 1968, Sagan received a bachelor's degree in 1955 and a master's degree in 1956, both in physics, and a doctorate in astronomy and astrophysics in 1960, all from the University of Chicago. He taught at Harvard University in the early 1960s before coming to Cornell, where he became a full professor in 1971.

Sagan played a leading role in NASA's Mariner, Viking, Voyager and Galileo expeditions to other planets. He has received NASA Medals for Exceptional Scientific Achievement and twice for Distinguished Public Service and the NASA Apollo Achievement Award.

His research has focused on topics such as the greenhouse effect on Venus; windblown dust as an explanation for the seasonal changes on Mars; organic aerosols on Titan, Saturn's moon; the long-term environmental consequences of nuclear war; and the origin of life on Earth. A pioneer in the field of exobiology, he continued to teach graduate and undergraduate students in courses in astronomy and space sciences and in critical thinking at Cornell.

The breadth of his interests were made evident in October 1994, at a Cornell-sponsored symposium in honor of Sagan's 60th birthday. The two-day event featured speakers in areas of planetary exploration, life in the cosmos, science education, public policy and government regulation of science and the environment -- all fields in which Sagan had worked or had a strong interest.

Sagan was the recipient of numerous of awards in addition to his NASA recognition. He has received 22 honorary degrees from American colleges and universities for his contributions to science, literature, education and the preservation of the environment and many awards for his work on the long-term consequences of nuclear war and reversing the nuclear arms race.

Among his other awards have been: the John F. Kennedy Astronautics Award of the American Astronautical Society; the Explorers Club 75th Anniversary Award; the Konstantin Tsiolkovsky Medal of the Soviet Cosmonauts Federation and the Masursky Award of the American Astronomical Society. He also was the recipient of the Public Welfare Medal, the highest award of the National Academy of Sciences, "for distinguished contributions in the application of science to the public welfare."

Sagan was elected chairman of the Division of Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society, president of the Planetology Section of the American Geophysical Union and chairman of the Astronomy Section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. For 12 years he was editor of Icarus, the leading professional journal devoted to planetary research.

He is co-founder of The Planetary Society, a 100,000-member organization and the largest space-interest group in the world. The society supports major research programs in the radio search for extraterrestrial intelligence, the investigation of near-Earth asteroids and, with the French and Russian space agencies, the development and testing of balloon and mobile robotic exploration of Mars. Sagan also was Distinguished Visiting Scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California and was contributing editor of Parade magazine, where he published many articles about science and, most recently, about the disease that he has battled for the past two years.

Sagan is survived by his wife and collaborator, Ann Druyan; his sister, Cari Sagan Greene; five children, Dorion, Jeremy, Nicholas, Sasha and Sam; and a grandson, Tonio.