Michael D. Robbins © 2003

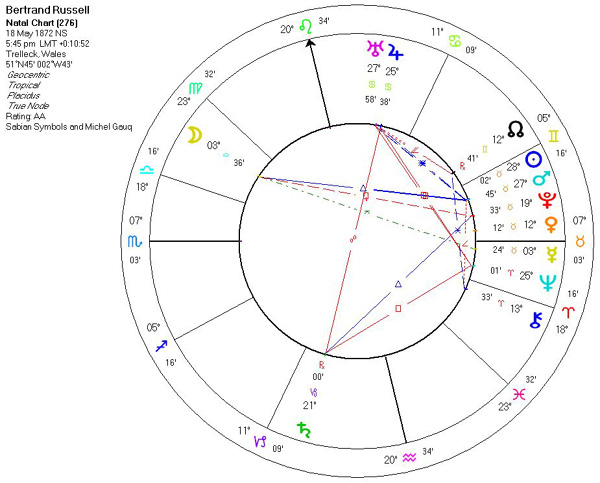

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

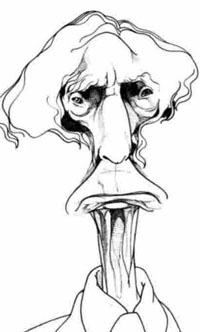

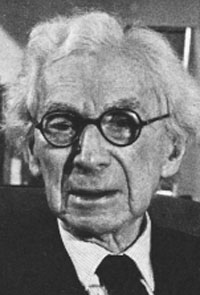

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

to Volume 3 Table of Contents

The world is full of magical things patiently waiting for our wits to grow sharper.

A life without adventure is likely to be unsatisfying, but a life in which adventure is allowed to take whatever form it will is sure to be short.

Against my will, in the course of my travels, the belief that everything worth knowing was known at Cambridge gradually wore off. In this respect my travels were very useful to me.

All movements go too far.

Almost everything that distinguishes the modern world from earlier centuries is attributable to science, which achieved its most spectacular triumphs in the seventeenth century.

Aristotle maintained that women have fewer teeth than men; although he was twice married, it never occurred to him to verify this statement by examining his wives' mouths.

Boredom is... a vital problem for the moralist, since half the sins of mankind are caused by the fear of it.

Both in thought and in feeling, even though time be real, to realise the unimportance of time is the gate of wisdom.

Conventional people are roused to fury by departure from convention, largely because they regard such departure as a criticism of themselves.

Democracy is the process by which people choose the man who'll get the blame.

Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.

Fear is the main source of superstition, and one of the main sources of cruelty. To conquer fear is the beginning of wisdom.

Freedom of opinion can only exist when the government thinks itself secure.

God is a reality of spirit... He cannot... be conceived as an object, not even as the very highest object. God is not to be found in the world of objects.

I believe in using words, not fists. I believe in my outrage knowing people are living in boxes on the street. I believe in honesty. I believe in a good time. I believe in good food. I believe in sex.

I did not know I loved you until I heard myself telling so, for one instance I thought, "Good God, what have I said?" and then I knew it was true.

I like mathematics because it is not human and has nothing particular to do with this planet or with the whole accidental universe - because, like Spinoza's God, it won't love us in return.

I think we ought always to entertain our opinions with some measure of doubt. I shouldn't wish people dogmatically to believe any philosophy, not even mine.

I would never die for my beliefs because I might be wrong.

I've made an odd discovery. Every time I talk to a savant I feel quite sure that happiness is no longer a possibility. Yet when I talk with my gardener, I'm convinced of the opposite.

If there were in the world today any large number of people who desired their own happiness more than they desired the unhappiness of others, we could have a paradise in a few years.

In all affairs it's a healthy thing now and then to hang a question mark on the things you have long taken for granted.

In America everybody is of the opinion that he has no social superiors, since all men are equal, but he does not admit that he has no social inferiors, for, from the time of Jefferson onward, the doctrine that all men are equal applies only upwards, not downwards.

It has been said that man is a rational animal. All my life I have been searching for evidence which could support this.

It is preoccupation with possessions, more than anything else, that prevents us from living freely and nobly.

It seems to be the fate of idealists to obtain what they have struggled for in a form which destroys their ideals.

Italy, and the spring and first love all together should suffice to make the gloomiest person happy.

Love is something far more than desire for sexual intercourse; it is the principal means of escape from the loneliness which afflicts most men and women throughout the greater part of their lives.

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell (May 18, 1872 - February 2, 1970) was one of the most influential mathematicians, philosophers and logicianss working (mostly) in the 20th century, an important political liberal, activist and a populariser of philosophy. Millions looked up to Russell as a sort of prophet of the creative and rational life; at the same time, his stance on many topics was extremely controversial. He was born in 1872, at the height of Britain's economic and political ascendancy, and died of influenza in 1970, when Britain's empire had all but vanished and her power had been drained in two victorious but debilitating world wars. At his death, however, his voice still carried moral authority, for he was one of the world's most influential critics of nuclear weapons and the American war in Vietnam.

In 1950, Russell was made Nobel Laureate in Literature "in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought".

Russell's philosophical and logical work

In mathematical logic, Russell established Russell's paradox, which exposed an inconsistency in naïve set theory and led directly to the creation of modern axiomatic set theory. It also crippled Gottlob Frege's project of reducing mathematics to logic. Nonetheless, Russell defended logicism (the view that mathematics is in some important sense reducible to logic) and attempted this project himself, along with Alfred North Whitehead, in the Principia Mathematica, a clean axiomatic system on which all of mathematics can be built, but which was never fully completed. Although it did not fall prey to the paradoxes in Frege's approach, it was later proven by Kurt Gödel that—for exactly that reason—neither Principia Mathematica nor any other consistent logical system could prove all mathematical truths, and hence Russell's project was necessarily incomplete.

Perhaps Russell's most significant contribution to philosophy of language is his theory of descriptions. It is normally illustrated using the phrase "the present King of France", as in "The present king of France is bald." What object is this sentence about, given that there is not, at present, a king of France? Alexius Meinong had suggested that we must posit a realm of "nonexistent entities" that we can suppose we are referring to when we use expressions like this; but this would be a strange theory, to say the least. Frege seemed to think we could dismiss as nonsense any sentences whose words apparently referred to objects that didn't exist. Among other things, the problem with this solution is that some such sentences, such as "If the present king of France is bald, then the present king of France has no hair on his head," not only do not seem nonsensical but appear to be obviously true. Roughly the same problem would arise if there were two kings of France at present: which of them does "the king of France" denote?

The problem is general to what are called "definite descriptions." Normally this includes all terms beginning with "the", and sometimes includes names, like "Walter Scott." (This point is quite contentious: Russell sometimes thought that the latter terms shouldn't be called names at all, but only "disguised definite descriptions," but much subsequent work has treated them as altogether different things.) What is the "logical form" of definite descriptions: how, in Frege's terms, could we paraphrase them in order to show how the truth of the whole depends on the truths of the parts? Definite descriptions appear to be like names that by their very nature denote exactly one thing, neither more or less. What, then, are we to say about the sentence as a whole if one of its parts apparently isn't working right?

Russell's solution was, first of all, to analyze not the term alone but the entire sentence that contained a definite description. "The present king of France is bald," he then suggested, can be reworded to "There is an x such that x is a present king of France, nothing other than x is a present king of France, and x is bald." Russell claimed that each definite description in fact contains a claim of existence and a claim of uniqueness which give this appearance, but these can be broken apart and treated separately from the predication that is the obvious content of the sentence they appear in. The sentence as a whole then says three things about some object: the definite description contains two of them, and the rest of the sentence contains the other. If the object does not exist, or if it is not unique, then the whole sentence turns out to be false, not meaningless.

One of the major complaints against Russell's theory, due originally to P. F. Strawson, is that definite descriptions do not claim that their object exists, they merely presuppose that it does.

Russell's epistemology went through many phases, most of which have since fallen by the wayside in philosophy. Nonetheless, his influence lingers on in the distinction between two ways in which we can be familiar with objects: "knowledge by acquaintance" and "knowledge by description." Russell thought that we could only be acquainted with our own "sense data," momentary perceptions of colours, sounds, and the like, and that everything else, including the physical objects that these were sense data of, could only be reasoned to--known by description--and not known directly. But the distinction has gained much wider application.

Russell is generally recognized as one of the founders of analytic philosophy. Alongside G. E. Moore he was largely responsible for the "revolt against Idealism" in British philosophy at the beginning of the twentieth century (which was echoed, thirty years later in Vienna, by the logical positivists' "revolt against metaphysics"). Russell and Moore strove to eliminate what they saw as meaningless and incoherent philosophy, and to seek clarity and precision in argument. Russell's logical work with Whitehead continued this project. Ludwig Wittgenstein was his student between 1911 and 1914, and he was responsible for having Wittgenstein's Tractatus published and for securing the latter a position at Cambridge and several fellowships. However, he came to disagree with Wittgenstein's later approach to philosophy, while Wittgenstein came to think of Russell as "superficial and glib." Russell's influence also lies heavily on the work of W. V. Quine, Karl Popper, and a number of others.

Russell's activism

was an outspoken pacifist. He opposed British participation in World War I and as a result was first fined, then lost his professorship at Trinity College of Cambridge University and was later imprisoned for six months. In the years leading to World War II, he supported the policy of appeasement, but later acknowledged that Hitler had to be defeated.

Russell called his stance "Relative Pacifism"—he held that war was always a great evil, but in some particularly extreme circumstances (such as when Hitler threatened to take over Europe) it might be a lesser of multiple evils.

On November 20, 1948, in a public speech at Westminster School, addressing a gathering arranged by the New Commonwealth, Russell shocked some of his less careful listeners by seeming to advocate a preemptive nuclear strike on the Soviet Union. Russell argued that war between the United States and the Soviet Union seemed inevitable, so it would be a humanitarian gesture to get it over with quickly. Currently, Russell argued, humanity could survive such a war, whereas a full nuclear war after both sides had manufactured large stockpiles of more destructive weapons was likely to result in the extinction of the human race. Russell later relented from this stance, instead arguing for mutual disarmament by the nuclear powers.

Starting in the 1950s, Russell became a vocal opponent of nuclear weapons. With the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs he released the Russell-Einstein Manifesto with Albert Einstein and organized several conferences. In 1961, he was imprisoned for a week in connection with his nuclear disarmament protests. He opposed the Vietnam War and along with Jean-Paul Sartre organized a tribunal intended to expose U.S. war crimes; this came to be known as the Russell Tribunal.

Russell wrote against Victorian notions of morality. His early writings expressed his opinion that sex between a man and woman who are not married to each other is not necessarily immoral if they truly love one another. This might not seem extreme by today's standards, but it was enough to raise vigorous protests and denunciations against him during his first visit to the United States. (Russell's private life was rather more hedonistic than his published writings revealed, but that was not yet well known at the time.)

He was an early critic of the official story in the John F. Kennedy assassination; his "16 Questions on the Assassination" from 1964 is still considered a good summary of the apparent inconsistencies in that case.

In matters of religion, Russell classified himself as a philosophical agnostic and a practical atheist. He wrote that his attitude towards the Christian God was the same as his attitude towards the Greek gods: strongly convinced that they don't exist, but not able to rigorously prove it. His position is explained in the essays Am I An Atheist Or An Agnostic? and Why I am not a Christian ISBN 0671203231.

Politically he envisioned a kind of benevolent democratic socialism. He was extremely critical of the totalitarianism exhibited by Stalin's regime. But perhaps paradoxically, he was also an early advocate of social engineering:

''The social psychologists of the future will have a number of classes of school children on whom they will try different methods of producing an unshakable conviction that snow is black. Various results will be arrived at. First, that the influence of the home is obstructive. Second, that not much can be done unless indoctrination begins before the age of ten. Third, that verses set to music and repeatedly intoned are very effective. Fourth, that the opinion that snow is white must be held to show a morbid taste for eccentricity.

...Although this science will be diligently studied, it will be rigidly confined to the governing class. The population will not be allowed to know how its convictions were generated. When the technique has been perfected, every government that has been in charge of education for a generation will be able to control its subjects securely without the need of armies or policemen.

-- , 1951, The Impact of Science on Society

was from an aristocratic English family. His paternal grandfather Lord John Russell had been a prime minister in the 1840s, and was himself the second son of the 6th Duke of Bedford, of a leading Whig/ Liberal family. His mother Viscountess Amberley (who died when he was 2) was herself from an aristocratic family, and was the sister of Rosalind, Countess of Carlisle. His parents were extremely radical for their times; his father Viscount Amberley (who died when Bertrand was 4) was an atheist who had consented to his wife's affair with their children's tutor. His godfather was Utilitarian philosopher John Stuart Mill. His early years were spent at Pembroke Lodge in Richmond Park.

Despite this eccentric background, Russell's childhood was relatively conventional. After his parents' death, Russell and his older brother Frank (the future 2nd Earl) were raised by their stauchly Victorian grandparents - the Earl and Countess Russell (Lord John Russell and his second wife Lady Frances Elliot). However, Russell departed from his grandparents' expectations of him starting with his marriage.

Russell first met the American Quaker, Alys Pearsall Smith, when he was seventeen years old. He fell in love with the puritanical, high-minded Alys who was connected to several educationists and religious activists, and married her in December 1894. Their marriage was ended by separation in 1911. Russell had never been faithful; he had passionate affairs with, among others, Lady Ottoline Morrell (half-sister of the 6th Duke of Portland) and the actress Lady Constance Malleson.

Russell studied philosophy and logic at Cambridge University, starting in 1890. He became a fellow of Trinity College in 1908. In 1920, Russell travelled to Russia and subsequently lectured in Peking on philosophy for one year.

In 1921, after Russell had lost his professorship, he divorced Alys and married Dora Russell nee Dora Black. Their children were John Conrad Russell (who briefly succeeded his father as 4th Earl Russell) and Lady Katherine Russell, now Lady Katherine Tait). Russell supported himself during this time by writing popular books explaining matters of physics, ethics and education to the layman. Together with Dora, he founded the experimental Beacon Hill school in 1927.

Upon the death of his elder brother in 1931, Russell became 3rd Earl Russell. It is, however, quite rare for him to be referred to by this title.

After Russell's marriage to Dora broke up over her adultery with an American journalist, in 1936 he took as his third wife, an Oxford undergraduate named Patricia ("Peter") Spence. She had been his children's governess in the summer of 1930. Russell and Peter had one son, Conrad.

In the spring of 1939, Russell moved to Santa Barbara to lecture at the University of California, Los Angeles. He was appointed professor at the City College of New York shortly thereafter, but after public outcries, the appointment was annulled by the courts: his radical opinions made him "morally unfit" to teach at the college. He returned to Britain in 1944 and rejoined the faculty of Trinity College.

In 1952, Russell divorced Peter and married his fourth wife, Edith (Finch). They had known each other since 1925. Edith had lectured in English at Bryn Mawr College, near Philadelphia.

wrote his three volume autobiography in the late 1960s and died in 1970 in Wales. His ashes were scattered over the Welsh mountains.

He was succeeded in his titles by his son by his second marriage to Dora Russell Black, and then by his younger son (by his third marriage to Peter). His younger son Conrad, 5th Earl Russell, is an elected hereditary peer to the British House of Lords, and a respected British academic.

A Chronology of Russell's Life

A short chronology of the major events in Russell's life is as follows:

(1872) Born May 18 at Ravenscroft, Wales.

(1874) Death of mother and sister.

(1876) Death of father; Russell's grandfather, Lord John Russell (the former Prime Minister), and grandmother succeed in overturning his father's will to win custody of Russell and his brother.

(1878) Death of grandfather; Russell's grandmother, Lady Russell, supervises his upbringing.

(1890) Enters Trinity College, Cambridge.

(1893) Awarded first class B.A. in Mathematics.

(1894) Completed the Moral Sciences Tripos (Part II)

(1894) Marries Alys Pearsall Smith.

(1900) Meets Peano at International Congress in Paris.

(1901) Discovers Russell's paradox.

(1902) Corresponds with Frege.

(1908) Elected Fellow of the Royal Society.

(1916) Fined 110 pounds and dismissed from Trinity College as a result of anti-war protests.

(1918) Imprisoned for five months as a result of anti-war protests.

(1921) Divorce from Alys and marriage to Dora Black.

(1927) Opens experimental school with Dora.

(1931) Becomes the third Earl Russell upon the death of his brother.

(1935) Divorce from Dora.

(1936) Marriage to Patricia (Peter) Helen Spence.

(1940) Appointment at City College New York revoked following public protests.

(1943) Dismissed from Barnes Foundation in Pennsylvania.

(1949) Awarded the Order of Merit.

(1950) Awarded Nobel Prize for Literature.

(1952) Divorce from Peter and marriage to Edith Finch.

(1955) Releases Russell-Einstein Manifesto.

(1957) Organizes the first Pugwash Conference.

(1958) Becomes founding President of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

(1961) Imprisoned for one week in connection with anti-nuclear protests.

(1970) Dies February 02 at Penrhyndeudraeth, Wales.

Bertrand Arthur William Russell was born at Trelleck on 18th May, 1872. His parents were Viscount Amberley and Katherine, daughter of 2nd Baron Stanley of Alderley. At the age of three he was left an orphan. His father had wished him to be brought up as an agnostic; to avoid this he was made a ward of Court, and brought up by his grandmother. Instead of being sent to school he was taught by governesses and tutors, and thus acquired a perfect knowledge of French and German. In 1890 he went into residence at Trinity College, Cambridge, and after being a very high Wrangler and obtaining a First Class with distinction in philosophy he was elected a fellow of his college in 1895. But he had already left Cambridge in the summer of 1894 and for some months was attaché at the British embassy at Paris.

In December 1894 he married Miss Alys Pearsall Smith. After spending some months in Berlin studying social democracy, they went to live near Haslemere, where he devoted his time to the study of philosophy. In 1900 he visited the Mathematical Congress at Paris. He was impressed with the ability of the Italian mathematician Peano and his pupils, and immediately studied Peano's works. In 1903 he wrote his first important book, The Principles of Mathematics, and with his friend Dr. Alfred Whitehead proceeded to develop and extend the mathematical logic of Peano and Frege. From time to time he abandoned philosophy for politics. In 1910 he was appointed lecturer at Trinity College. After the first World War broke out, he took an active part in the No Conscription fellowship and was fined £ 100 as the author of a leaflet criticizing a sentence of two years on a conscientious objector. His college deprived him of his lectureship in 1916. He was offered a post at Harvard university, but was refused a passport. He intended to give a course of lectures (afterwards published in America as Political Ideals, 1918) but was prevented by the military authorities. In 1918 he was sentenced to six months' imprisonment for a pacifistic article he had written in the Tribunal. His Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy (1919) was written in prison. His Analysis of Mind (1921) was the outcome of some lectures he gave in London, which were organized by a few friends who got up a subscription for the purpose.

In 1920 Russell had paid a short visit to Russia to study the conditions of Bolshevism on the spot. In the autumn of the same year he went to China to lecture on philosophy at the Peking university. On his return in Sept. 1921, having been divorced by his first wife, he married Miss Dora Black. They lived for six years in Chelsea during the winter months and spent the summers near Lands End. In 1927 he and his wife started a school for young children, which they carried on until 1932. He succeeded to the earldom in 1931. He was divorced by his second wife in 1935 and the following year married Patricia Helen Spence. In 1938 he went to the United States and during the next years taught at many of the country's leading universities. In 1940 he was involved in legal proceedings when his right to teach philosophy at the College of the City of New York was questioned because of his views on morality. When his appointment to the college faculty was cancelled, he accepted a five-year contract as a lecturer for the Barnes foundation, Merion, Pa., but the cancellation of this contract was announced in Jan. 1943 by Albert C. Barnes, director of the foundation.

Russell was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1908, and re-elected a fellow of Trinity College in 1944. He was awarded the Sylvester medal of the Royal Society, 1934, the de Morgan medal of the London Mathematical Society in the same year, the Nobel Prize for Literature, 1950.

In a paper "Logical Atomism" (Contemporary British Philosophy. Personal Statements, First series. Lond. 1924) Russell exposed his views on his philosophy, preceded by a few words on historical development.1