Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

Happiness hates the timid! So does science!

Man's loneliness is but his fear of life.

Obsessed by a fairy tale, we spend our lives searching for a magic door and a lost kingdom of peace.

(Mercury Scorpio trine Moon Pisces)When you're 50 you start thinking about things you haven't thought about before. I used to think getting old was about vanity - but actually it's about losing people you love. Getting wrinkles is trivial.

I love every bone in their heads.

ATTRIBUTION: On critics, quoted by Brooks Atkinson on accepting a medal from the Theater Committee for Eugene O’Neill, NY Times 1 Dec 80

(Jupiter and Mars in Sagittarius; Mercury in Scorpio)[Her] love and tenderness … gave me the faith in love that enabled me to face my dead at last and write this play—write it with deep pity and understanding and forgiveness for all the four haunted Tyrones.

ATTRIBUTION: Dedication to his wife Carlotta in Long Day’s Journey into Night,

(Libra Sun; Pisces moon; Mercury Scorpio)There is no present or future, only the past, happening over and over again, now.(1888 - 1953)

A man's work is in danger of deteriorating when he thinks he has found the one best formula for doing it. If he thinks that, he is likely to feel that all he needs is merely to go on repeating himself . . . so long as a person is searching for better ways of doing his work, he is fairly safe.(1888 - 1953)

The child was diseased at birth, stricken with a hereditary ill that only the most vital men are able to shake off. I mean poverty - the most deadly and prevalent of all diseases.(1888 - 1953)

Everything looked and sounded unreal. Nothing was what it is. That's what I wanted -- to be alone with myself in another world where truth is untrue and life can hide from itself.

(Piscess moon)“Curiosity killed the cat, but satisfaction brought it back”

“When men make gods, there is no God”

“The old / like children / talk to themselves, for they have reached that hopeless wisdom of experience which knows that though one were to cry it in the streets to multitudes, or whisper it in the kiss to one's beloved, the only ears that can ever hear one's secrets are one's own!” quote

“One should either be sad or joyful. Contentment is a warm sty for eaters and sleepers.”

(Mercury in Scorpio)“The iceman cometh”

It is Mystery -- the mystery any one man or woman can feel but not understand as the meaning of any event -- or accident -- in any life on earth ... [that] I want to realize in the theatre. The solution, if there ever be any, will probably have to be produced in a test tube and turn out to be discouragingly undramatic.

To hell with the truth! As the history of the world proves, the truth has no bearing on anything. It's irrelevant and immaterial, as the lawyers say. The lie of a pipe dream is what gives life to the whole misbegotten mad lot of us, drunk or sober

I hold more and more surely to the conviction that the use of masks will be discovered eventually to be the freest solution of the modern dramatist's problem as to how -- with the greatest possible dramatic clarity and economy of means -- he can express those profound hidden conflicts of the mind which the probings of psychology continue to disclose to us., "Memoranda on Masks"

I am far from being a pessimist. . . . On the contrary, in spite of my scars, I am tickled to death at life.

(Scorpio and Sagittarius)If a person is to get the meaning of life he must learn to like the facts about himself -- ugly as they may seem to his sentimental vanity -- before he can learn the truth behind the facts. And the truth is never ugly.

"I lay on the bowsprit, with the water foaming into spume under me, the masts with every sail white in the moonlight towering above me. I became drunk with the beauty and singing rhythm of it, and for a moment lost myself- actually lost my life. I was set free... dissolved in the sea, became white sails and flying spray, became beauty and rhythm and the high dim-starred sky... I belonged within a unity and joy to life itself."

"For a moment I lost myself, actually lost my life. I was set free! I belonged, without past or future, within peace and unity and a wild joy, within something greater than my own life . . . to life itself. I caught a glimpse of something greater than myself."

Censorship of anything, at any time, in any place, on whatever pretense, has always been and will always be the last resort of the boob and the bigot.

I knew it. I knew it. Born in a hotel room, and God damn it, died in a hotel room.

Last words_______________________________

It was a great mistake my being born a man. I would have been much more successful as a sea-gull or a fish. As it is, I will always ge a stranger who never feels at whome, who does not really want is not really wanted, who can never belong, who must always be a little in love with death!

--- Edmund, the youngest Tyrone son and the playwright's alter ego, in Long Day's Journey Into Night.Well, spring isn't everything, is it, Essie? There's a lot to be said for autumn. That's got beauty, too. And winter -- if you're together.

Father to Mother in Eugene O'Neill's only comedy Ah, Wilderness!It's better Anna live on farm den she don't know dat ole devil, sea-

- Chris, Anna Christie, Act 1We's all poor nuts and things happen, and we yust get mixed in wrong, that's all. -- ibid Act 4

Man is born broken. He lives by mending. The grace of God is glue

-- Brown, The Great God Brown, Act 4, scene 1Love is a word--a shameless ragged ghost of a word--begging at all doors for life at any price!

--Prologue, The Great God BrownYou become such a coward you'll grab at any lousy excuse to get out of killing your pipe dreams. And yet, as I've told you over and over, it's exactly those damned tomorrow dreams which keep you from making peace with yourself

--Hickey in The Iceman Cometh, Act 3If I had any nerves, I'd have a nervous breakdown

--Ed Mosher in The Iceman Cometh Act 1Yank: Sure! Lock me up! Put me in a cage! Dat's de on'y answer yuh know. G'wan, lock me up!

Policeman: What you been doin'?

Yank: Enough to gimme life for! I was born, see -- The Hairy Ape. scene 7

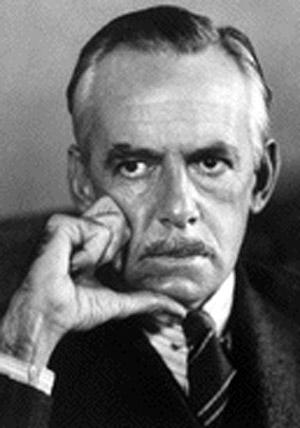

Eugene O'Neill, American playwright

Born October 16, 1888

New York, New York, USA

Died November 27, 1953Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was a Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-winning American playwright. More than any other dramatist, O'Neill introduced the dramatic realism pioneered by Anton Chekhov, Henrik Ibsen, and August Strindberg into American drama, and was the first to use truly American vernacular in his speeches. His plays involve characters who inhabit the fringes of society, where they struggle to maintain their hopes and aspirations but ultimately slide into disillusionment and despair. O'Neill wrote only one comedy (Ah, Wilderness!); all his other plays involve some degree of tragedy or personal pessimism.He was also part of the modern movement to revive the classical heroic mask from ancient Greek theatre and Japanese Noh theatre in some of his plays.[1]

O'Neill was very interested in the Faust theme, especially in the 1920s.[2]

C Life's life was connected to New London, Connecticut. His father was an Irish-born stage actor named James O'Neill, who had grown up in impoverished circumstances. He became famous for playing the title role in a stage version of The Count of Monte Cristo. His mother, Ella Quinlan O'Neill, was the emotionally fragile daughter of a wealthy father who died when she was seventeen. Recent research has clearly shown that Ella's father had Armenian roots.[citation needed] O'Neill's mother never recovered from the death of her second son, Edmund, who had died of measles at the age of two. She later became addicted to morphine as a result of Eugene O'Neill's difficult birth.

O'Neill was born in a Broadway hotel room. Because of his father's profession, O'Neill was sent to a Catholic boarding school where he found his only solace in books.

After being suspended from Princeton University, he spent several years at sea, during which time he suffered from depression and alcoholism. O'Neill's parents and older brother Jamie (who drank himself to death at the age of 45) died within three years of one another, and O'Neill turned to writing as a form of escape. Despite suffering from depression while he was at sea, O'Neill had a deep love for the sea, and it became a prominent theme in most of his plays, with several plays actually taking place on ships like the ones that he worked on.

While he was associated with the Provincetown Players, several of his early plays were put on by that group of actors and playwrights. O'Neill had previously been employed by the New London Telegraph, writing poetry as well as reporting. It wasn't until his experience in 1912–13 at a sanatorium (where he was recovering from tuberculosis) that he decided to devote himself full time to writing plays. (Connecticut College maintains the Louis Sheaffer Collection, consisting of material collected by O'Neill's most thorough biographer. The principal collection of O'Neill papers is at Yale University. The Eugene O'Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Connecticut fosters the development of new plays under his name.)

During the 1910s O'Neill was a regular on the Greenwich Village literary scene, where he also befriended many radicals, most notably Communist Party USA founder John Reed. O'Neill also at one time had a romantic relationship with Reed's wife, writer Louise Bryant. O'Neill was portrayed by Jack Nicholson in the 1981 film Reds about the life of John Reed, in which he served as the film's voice of anti-facism and cynicism.

O'Neill was married to Kathleen Jenkins from 1909 to 1912, during which time they had one son, Eugene Jr. In 1917, O'Neill met Agnes Boulton, a successful writer of commercial fiction, and they married in April 1918. The years of their marriage — during which the couple had two children, Shane and Oona — are described vividly in her 1958 memoir Part of a Long Story. They divorced in 1929, after O'Neill abandoned Boulton and the children for the actress Carlotta Monterey.

In 1929 O'Neill and Monterey moved to the Loire Valley of northwest France, where they lived in the Chateau du Plessis in St. Antoine-du-Rocher, Indre-et-Loire. He moved to Danville, California in 1937 and lived there until 1944. His house there (known as Tao House), is today the Eugene O'Neill National Historic Site.

O'Neill's first published play, Beyond the Horizon, opened on Broadway in 1920 to great acclaim, and was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. His best-known plays include "Anna Christie" (Pulitzer Prize 1922), Desire Under the Elms 1924, Strange Interlude (Pulitzer Prize 1928), Mourning Becomes Electra 1931, and his only comedy Ah, Wilderness!, a wistful re-imagining of his own youth as he wished it had been. In 1936 he received the Nobel Prize for Literature. After a ten-year pause, O'Neill's now-renowned play The Iceman Cometh was produced in 1946. The following year's A Moon for the Misbegotten failed, and would not gain recognition as being among his best works until decades later.

In the first years of their marriage, Monterey organized O'Neill's life, making it possible for him to devote himself to writing. However, she later became addicted to potassium bromide and the marriage deteriorated, resulting in a number of separations. (O'Neill always complained about her cooking, maintaining that the only thing she knew how to make was chili with cornbread.) She was dramatic and shallow, but O'Neill needed her, and she needed him. Although they separated several times, they never divorced.

In 1943, O'Neill disowned his daughter Oona for marrying the English actor, director and producer Charlie Chaplin when she was 18 and Chaplin was 54. He never saw Oona again.

He also had distant relationships with his sons, Eugene O'Neill Jr., a Yale classicist who suffered from alcoholism, and committed suicide in 1950 at the age of 40, and Shane O'Neill, a heroin addict who also committed suicide.

After suffering from multiple health problems (including alcoholism) over many years, O'Neill ultimately faced a severe Parkinsons-like tremor in his hands which made it impossible for him to write (he had tried using dictation but found himself unable to compose in that way) during the last 10 years of his life.

O'Neill died in room 401 of the Sheraton Hotel in Boston, on November 27, 1953, at the age of 65. (The building is now the Shelton Hall dormitory at Boston University) A revised analysis of his autopsy report shows that, contrary to the previous diagnosis, he did not have a Parkinson's disease but a late-onset cerebellar cortical atrophy. He was interred in the Forest Hills Cemetery in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts. O'Neill's final words were, "Born in a hotel room… and God dammit, died in one!"

Although his written instructions had stipulated that it not be made public until 25 years after his death, in 1956 Carlotta arranged for his autobiographical masterpiece Long Day's Journey Into Night to be published, and produced on stage to tremendous critical acclaim and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1957. This last play is now considered to be his finest play. Other posthumously-published works include A Touch of the Poet (1958) and More Stately Mansions (1967).

Eugene O'Neill (1888 - 1953) Playwright American playwright who brought a literary sensibility and many experimental techniques to the American stage in his portrayals of everything from Greek tragedy to the abysmal depths of alcoholism

Biography

Born October 16, 1888 in New York, New York Ethnicity Irish Residences Georgia, Connecticut, Massachusetts, California, New York

Died November 27, 1953 in Boston, Massachusetts Nationality American Language English

Other occupations Sailor, Secretary, Reporter, Mule Tender, Beachcomber, Draughtsman, ProspectorEugene O'Neill was born October 16, 1888 in New York, the third son of a dysfunctional family with strong ties to the theater.

Eugene's mother Ellen became a life long drug addict after she was morphine by her physician to recover from Eugene's birth. As a boy, O'Neill attended a number of Catholic schools while the family traveled with his father, Eugene Sr., who played the title role in a traveling production of The Count of Monte Cristo. The instability of this life took its toll on the family, especially on his mother Ellen whose drug use increased during this period. Two of the greatest influences of O'Neill's early life were his family's Irish Catholicism and his older, dissolute brother Jaime who Eugene admired and soon took after.

In 1902, his parents sent O'Neill to a prep boarding school in Connecticut where their wayward son spent much of his time discovering the seedier side of life with his brother Jaime. In 1906, O'Neill attended Princeton University, but his interest in carousing soon took precedence. He said this period of life was one of 'booze, books, and broads' (mostly prostitutes). He was suspended from Princeton in 1907 for breaking a window in a railroad stationmaster's house.

After leaving university, Eugene married Kathleen Jenkins in 1909 and continued his debauched ways while trying to hold down a job with the New York-Chicago Supply Company. His family disapproved of the marriage and forced Eugene to set sail for Honduras where he was to prospect for gold. By this time, Kathleen was already pregnant; she gave birth to Eugene Gladstone Jr. in 1910. O'Neill returned from Honduras after contracting Malaria, but soon set sail again aboard a Norwegian ship.

He lived for a time in Buenos Aires, Liverpool and New York, barely surviving with a few menial jobs and lots of begging. In 1912, Eugene almost ended his life with an overdose of Veronal in Jimmy-the-Priest's, a dive bar where Eugene was living in a back room. After recovering with the help of us family, O'Neill toured with his father's company for awhile and then worked as a reporter for The New London Telegraph, where he also contributed poetry. O'Neill's fledgling journalistic career was sidelined when he was diagnosed with tuberculosis at the end of 1912.

During the six months he spent months recuperating at Gaylord Farm Sanatorium, Eugene started writing plays and discovered his life's calling: to be a serious playwright. Eugene's first four plays, all written in 1913, were melodramas, a dramatic form that ruled the American stage at the time. Upon the suggestion of critic Clayton Hamilton, Eugene privately published these early plays under the title Thirst and Other One Act Plays in 1914, but the book went relatively unnoticed.

With the help of his father, O'Neill enrolled in George Pierce Baker's renowned play writing course at Harvard in the fall of 1914, where he produced a few plays, most of which he later destroyed. Though O'Neill valued the experience, he did not return for the second year of the program and instead moved to Greenwich Village in 1915 where he was a regular patron of another dive bar, The Hell Hole. The following year Eugene moved to Provincetown, Massachusetts where he at last found a group of performers who shared his experimental dramatic sensibility and appreciated the depiction of derelicts, prostitutes and God's injustice found in the playwrights early works. The group had organized their own theater company, The Provincetown Players, and decided to produce O'Neill's play Bound East for Cardiff. The play debuted in July 28, 1916 and was a moderate success. This success started O'Neill writing again and he produced two more one act plays by the end of the summer.

In the fall of 1916, the Provincetown Players moved to New York and produced four of O'Neill’s one act plays in their first season, helping to established the young author's reputation in the theatrical capital of America. O'Neill remained in Provincetown and began living with Agnes Boulton, a young magazine editor, in the fall of 1917. During the winter, he continued writing at a rapid pace, producing 5 more plays, and had his first play produced outside of the Provincetown Players. Agnes and Eugene married in the spring of 1918, but the marriage was rocky from the start. Over the next few years, O'Neill continued to write plays at a fairly rapid and regular pace. Many of his plays were produced during this period and helped establish his reputation as one of America's most promising young playwrights.

In 1919, O'Neill and his wife moved to an isolated home on the coast of Massachusetts where the couple's drinking and fighting intensified. By this time, O'Neill was the father of two young children, but he was a rather cold father who saw his children as distractions from his work more than anything else. In 1920, his father, who Eugene had recently reconciled with, fell ill and died. In the early 1920's, O'Neill produced the finest plays of his early period, Anna Christie, Emperor Jones and The Hairy Ape. With these plays, O'Neill came of age as a playwright and introduced expressionistic techniques to the American stage for the first time. Throughout the 1920's, Eugene continued writing plays that featured expressionistic techniques and tackled such controversial topics as miscegenation. During this period, Eugene didn't confine himself to contemporary settings. He wrote The Fountain about a 17th century conquistador and based Marcos Millions on Marco Polo's journey to Asia. By the end of the decade O'Neill had established himself as America's foremost playwright.

The 1928 production of Marcos Millions began O'Neill's lifelong association with the Theater Guild, a wealthy New York production company interested in promoting new playwrights and experimental theater. The first play to prominently feature O'Neill's trademark use of masks was The Great God Brown, produced in 1926. O'Neill enjoyed his first popular success with Strange Interlude in 1928.

The five hour long production, which was one of the first plays to introduce Freudian themes to the American stage, ran for 426 performances. Though a raging alcoholic, Eugene was 'strictly on the wagon' while writing because his labor-intensive method of composition (extensive rewrites, outlines and reams of research notes) demanded such intense clarity and focus that he could not afford a binge.

With the help of intense psychological treatment, O'Neill gave up drinking in 1926, with the exception of two brief relapses. In the late 1920's, O'Neill became involved with Carlotta Monterey, a young mentally unstable actress, and eventually moved to France to live with her. In 1929, after a bitter divorce from Agnes, O'Neill and Carlotta married in Paris. Carlotta proved to be a valuable asset for her husband's literary career by managing his daily affairs and limiting his visitors so he could concentrate on his work.

From 1929 to 1931, while in France with Carlotta, Eugene wrote the Mourning Becomes Electra, a series of three plays based on the ancient Greek tragic trilogy Oresteia, but set in the American South shortly after the Civil War. This play marked the end of O'Neill's experimental period and a return to more traditional dramatic techniques; gone were the masks of The Great God Brown and the internal thoughts spoken by a chorus as featured in Strange Interlude. O'Neill sought something simpler and more subtle in developing a new dramatic language for modern tragedy. The couple returned to New York in 1931 to oversee the production of the trilogy. Unfortunately, the plays were not entirely successful and caused confusion among many critics. Carlotta thought it best that Eugene live in isolated locations so he could be free of distractions so the couple moved to a remote house in Sea Island, Georgia in the early 1930's. There, Eugene began working on Ah, Wilderness!, a lighthearted play about an idyllic rural childhood that became O'Neill's greatest popular success when it was produced in 1933. At the height of this popularity, O'Neill exiled himself from the New York theater scene, disliking its increasing commercialization, and moved to the Tau House, an estate in Danville, California.

For the rest of the 1930's, Eugene worked on a cycle of 11 plays that was to trace an American Family from 1800 to the present day. Unfortunately, he finished only one play, A Touch of a Poet, before abandoning the project in 1939. O'Neill and his wife destroyed all of the unfinished manuscripts in the early 1950's except for More Stately Mansions, which they missed by accident. Despite the onset of a Parkinson-like disease that made the physical act of writing very difficult, O'Neill embarked upon an extremely productive period in the early 1940's during which he wrote a number of his masterpieces, including The Iceman Cometh and A Long Day's Journey into Night. Though he had completed both of these plays by the early 1940's, O'Neill waited for World War II to end before returning to the New York stage, fearing that the despairing view of life expressed in these plays would not be well received while war still raged.

After a 13 year absence, O'Neill returned to Broadway with The Iceman Cometh in 1946. It was to be O'Neill's last Broadway production during his lifetime. With A Long Day's Journey Into Night, O'Neill had at last transcended the constraints of melodrama and produced the unique dramatic statement he had been trying to write his entire life, but, due to the extensive autobiographical content in the play, O'Neill did not want the play produced until 25 years after his death. His widow disregarded these wishes and authorized a production in Stockholm, Sweden in 1956, a mere three years after her husband's death. O'Neill also planned a series of one act plays where a character would deliver a monologue to The Good Listener, represented on stage by a life-size marionette, but only one play, Hughie, came from this project. He completed his last play, A Moon for the Misbegotten, in 1943. After the failed 1947 Off-Broadway production of A Moon for the Misbegotten, O'Neill gave up writing altogether. By this time, O'Neill's health was failing and he refused to use dictation, claiming that he could not create without a pencil and paper. In his last years, Eugene suffered through his fist son' suicide, his second son's arrest for heroin possession and his wife's increasing mental instability. Unable to write, Eugene retreated from his turbulent domestic life to a Boston hotel room where he waited to die. On November 27, 1953, America's first great playwright died alone, broken and largely forgotten, much like many of his own characters. The production in the mid-1950's of his two last great plays, The Iceman Cometh and A Long Day's Journey Into Night, sparked a renewed interest in O'Neill and he was finally hailed as the true father of American theater and one of the greatest playwrights the country had ever produced.