Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

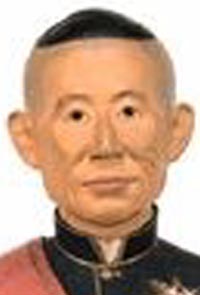

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

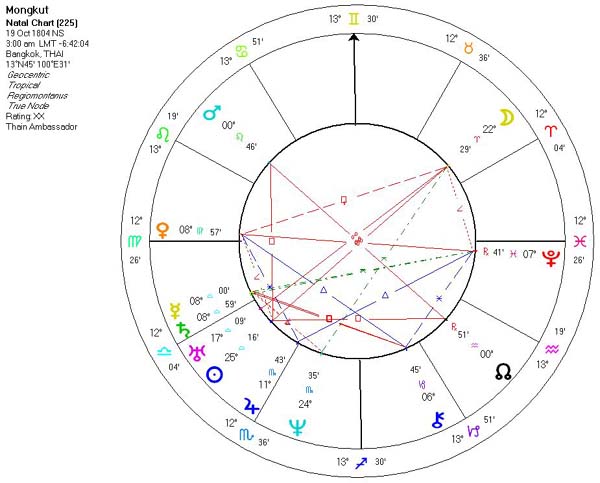

King Mongkut (Rama IV), (October 18, 1804 - October 18, 1868) was king of Thailand from 1851 to 1868. Historians have widely regarded him as one of the most remarkable kings of the Chakri Dynasty. Prince Mongkut was the son of King Rama II and his first wife Queen Sri Suriyendra, whose first son died at birth in 1801. Prince Mongkut was five years old when his father succeeded to the throne in 1809. According to the law of succession, he was the first in line to the throne; but when his father died, his influential half-brother, Nangklao, was strongly supported by the nobility to assume the throne. Prince Mongkut decided to enter the Buddhist priesthood and travelled in exile to many locations in Thailand. Prince Mongkut spent the following twenty-seven years searching for Western knowledge; he had studied Latin, English, and astronomy with missionaries and sailors. Prince Mongkut would later be noted for his excellent command of English, although it is said that his younger brother, Vice-King Pinklao, could speak even better English.

After his twenty-seven years of pilgrimage, King Mongkut succeeded to the throne in 1851. He took the name Phra Chom Klao, although foreigners continued to call him Mongkut. His awareness of the threat from the British and French imperial powers, led him to many innovative activities. He ordered the nobility to wear shirts while attending his court; this was to show that Siam was no longer barbaric from the Western point of view. King Mongkut hired an English woman, Anna Leonowens, whose influence was later the subject of great Thai controversy, to be his sons' tutor. It is still debated how much this affected the worldview of one of his sons, Prince Chula, who succeeded to the throne. Anna claimed that her conversations with Prince Chula about human freedom, and her relating to him the story of Uncle Tom's Cabin, became the inspiration for his abolition of slavery almost 40 years later. Leonowns' story would become the inspiration for the American musical The King and I.

As king, Mongkut worked to established the Thammayut Nikaya, an order of Buddhist monks that he believed would conform more closely to the orthodoxy of the Theravada school.

One of King Mongkut's last official duties came in 1868, when he invited the British consuls from Singapore to watch the solar eclipse, which Mongkut had predicted two years earlier, at Wakor district in Prachuap Khiri Khan province. This became perilous when Mongkut and Prince Chula were infected with malaria. The king died several days later, and was succeeded by his son, who survived the malaria.

Reportedly, Mongkut once remarked to a Christian missionary friend: "What you teach us to do is admirable, but what you teach us to believe is foolish".King Mongkut of Siam

The Prince Who Became a Monk

Prince Maha Mongkut was born on October 18, 1804 in the kingdom of Siam (now called Thailand). His father, Buddha Loetla Nabhalai, became the king of Siam (King Rama II) when Mongkut was five. Mongkut's mother was Queen Sri Suriyendra.

As was traditional, Mongkut's father kept a large harem. Mongkut had 72 brothers and sisters, borne by 38 different mothers, but Mongkut was the crown prince, expected to inherit the throne after his father's death. He was called Chao Fah Mongkut, meaning "The High Prince of the Crown." Until he was nine Mongkut lived in a palace near the Chao Phraya River, where he studied Buddhism, history and literature. He also learned to ride horses and elephants, and was trained in the use of various weapons. When he was just 12 years old, his father put him in charge of the Siamese army.

But Mongkut had a rival for the throne -- his half-brother Jetta or Chesdabodin, the son of one of Rama II's many consorts. Prince Jetta was seventeen years older than Mongkut, more experienced in government, and much more powerful.

When Mongkut was 20, his father died and a council of princes and court officials chose Jetta to be Siam's new king. Fearing for his safety, Mongkut left his wife and two young children and became a Buddhist monk. For 27 years the former crown prince lived a monastic life, but it was hardly a dull life. He travelled barefoot throughout Siam, living on handouts and learning about the way ordinary people lived. He also devoted himself to intellectual studies, learning everything from printing to astronomy. He founded the strict Thammayut monastic sect, which still exists today.

Mongkut as King

In 1851, Jetta (now called King Nangklao or Rama III) died. At last Mongkut was elected to ascend the throne. At the age of 47 he left the monkhood and became King Phrachomklao or Rama IV. One of his first acts as monarch was to name a deputy king. This was his brother Chutamani, another son of Queen Sri Suriyendra. Chutamani, now known as King Pinklao, took charge of Siam's national defense.

Mongkut was a true monarch, with total power over his five and a half million subjects. But he was different from previous Siamese kings. For one thing, he was friendly toward the West, inviting European diplomats to his coronation and introducing Western innovations into his kingdom. He spoke English, French, and Latin as well as Siamese, Pali, and Sanskrit, although he joked once that some Englishmen "have not understanding of their own language when I speak."

Despite his open-mindedness about other cultures, Mongkut made sure that Siam did not become a mere appendage of some Western nation.

In his personal life Mongkut adhered to Siamese tradition, having 82 children by 39 wives. Nine thousand women lived in his harem, kept apart from the world in a separate city that they were seldom allowed to leave. But Mongkut wanted the women of his court to be educated about the world beyond Siam. He arranged for them to receive English lessons from Christian missionaries, but the Siamese women were bored by their preaching. So Mongkut's consul in Singapore hired another woman, Anna Leonowens, to teach the king's wives and children. She arrived in Bangkok in 1862.

The Famous Governess

According to her own writings, Mrs. Leonowens had been born in Wales in 1834. Her father, a military man, was sent to India when Anna was six. He took his wife went with him, but young Anna was left behind at a girls' school run by a relative. Her father died in India, and Anna was not reunited with her mother until she was 15.In 1851 Anna married a British officer, Major Thomas Leonowens. Her husband died young. Left with two children to support, Anna turned to teaching.

Although historians question the accuracy of Anna's version of her life story as well as her account of life in the Siamese court, her two books (The English Governess at the Siamese Court and The Romance of the Harem) created great interest in King Mongkut and Siam that continues to this day. Eventually author Margaret Landon converted Leonowens' books into the very popular novel Anna and the King of Siam, published in 1944. It was made first into a movie starring Rex Harrison, then into a Broadway musical, The King and I, starring Yul Brynner, which became a movie. It was followed by a 1972 television series, also starring Brynner. In March 1999 an animated version of "The King and I" was released.

The most recent film adaptation is Anna and the King, released in late 1999 and starring Jodie Foster as Anna. Like its predecessors, "Anna and the King" has been banned in Thailand due to its historical inaccuracy and what Thai censors perceive as its disrespect for the monarchy.

The Death of King Mongkut

In 1868, King Mongkut impressed astronomers by predicting a solar eclipse. Unfortunately, Mongkut and his 15-year-old son Chulalongkorn observed the eclipse from a marshy area infested with mosquitoes, and both contracted malaria. Knowing that he was dying, Mongkut called his advisors to his bedside and urged them to continue working for the best interests of his people. King Mongkut died on his 64th birthday.

Chulalongkorn recovered. Because he was his father's eldest royal son (his mother was Queen Thepserin), he succeeded to the throne as King Rama V.

Mrs. Leonowens was away from Siam when Mongkut died. She wrote the new king a letter of condolence. He replied politely, but did not invite her back to Siam. So Leonowens made a new life as a writer. She became well-known and successful.

Mongkut's prime minister ruled as regent until Chulalongkorn turned 20 and took charge of the country. He immediately turned tradition on its ear by announcing that the people of Siam were no longer required to prostrate themselves in the king's presence. He also abolished slavery and gave up his official ownership of all the land in Siam. His grandson, Bhumibol, is Thailand's current king.Mongkut or Rama IV [räm'u] , 1804–68, king of Siam, now Thailand (1851–68). A devout Buddhist monk, he was displaced in succession to the throne by his brother, who ascended as Rama III. Mongkut became king as Rama IV in 1851, and then used his knowledge, especially of the West, accumulated during his long years of study, to further his country's interests. He established diplomatic relations with several European countries and the United States, opened Siam to Western trade, and undertook extensive internal reform in all fields. Because of these measures, Siam was the only country in Southeast Asia not to fall under Western control in the 19th cent. He was succeeded by his son Chulalongkorn. Mongkut was made famous in the West by Margaret Landon's book Anna and the King of Siam (1944), which was based on the reminiscences of Anna Leonowens, a British governess at the court of Siam.

Mongkut, who was born in 1804, spent more than half his adult life in the yellow robe of a Buddhist monk. For 27 years, he traveled the countryside with his alms bowl, ate one meal a day and studied scripture; for years he served as abbot at a quiet riverside temple on the outskirts of Bangkok. It was there that royal emissaries found him one steamy April morning in 1851, when they brought the news that his half brother, King Rama III, was dead.

Within days, the 47-year-old monk stepped from monastic life into the rich temptations and intricacies of the palace, with its inner city thronging with hundreds of women, its precincts patrolled by female guards and its life revolving entirely around his royal person. The holy man was now officially the "Lord of Life," the fourth ruler in Siam's Chakri dynasty, able to exert life-or-death control over some 5.5 million subjects. (As king, he banned the death penalty for monks who broke their vows of celibacy, putting them to work, instead, cutting grass for the royal elephants.) A spectacular coronation inaugurated the reign with great pomp. Brahmin priests sounded ceremonial conch shells. The new monarch, clad in golden robes, was carried off in a gilded palanquin. Even in that moment of glory, though, Mongkut made clear that he would scrutinize tradition more critically than had previous rulers. For the first time in 200 years Western diplomats were invited, and Buddhist monks played a visible role in the ceremony. This was just the kind of gesture feared by Siam's conservative nobility.

Once crowned, Mongkut traveled more widely than any other king had, revisiting many of the paths that he trod barefoot as a monk. Like Rex Harrison and Yul Brynner's monarch, he relaxed the stiff protocol of royal visits, permitting foreigners to salute him according to their own customs.

He had long observed the growing number of European steamships entering Bangkok's port and understood their importance. (The stage and screen king grasped this, too, but in those kindergarten versions, Mongkut caught up with Western studies only under Anna's tutelage.) The king's learning and discipline were formidable. He studied Latin with a helpful French bishop. He also acquired English from American missionaries, a Promethean task at a time when no Thai-English dictionary existed. To translate from Thai to English, the king first had to find a comparable word in ancient Sanskrit, then plow his way through the bulky Sanskrit-English dictionary to find a near match. It was not surprising that he sometimes startled visitors with a colorful turn of phrase. "There are Englishmen," he joked to one Scotsman, "who have not understanding of their own language when I speak."

Reading the English newspapers from Singapore and Hong Kong, the king followed the expansion of empires. Siam was a strong force in Southeast Asia, but European powers hungered on a global scale. His response to all that was like the insight gained from a koan: to escape dominion by any one Western power, he would open his doors to all. He signed trade treaties with England, France, the United States and half a dozen other countries, thereby limiting his vulnerability to each.

In cementing these relations, the king displayed a sensitivity to each country's situation. A royal letter to President Franklin Pierce included an unusually intimate daguerreotype portrait. It shows Mongkut bareheaded, wearing a simple robe and seated beside Queen Thepserin, mother of the future king Chulalongkorn. No throne or crown appears in the portrait destined for the land without royalty. His letters to Queen Victoria, on the other hand, invoked the bond of noble blood.

Mongkut was fascinated by the precision of Western scientific measurement. He filled his chambers with clocks, thermometers and barometers, and taught himself astronomy, erecting an observatory on the palace grounds. This led to his greatest scientific triumph-and, indirectly, to his death. In August 1868, the palace announced an expedition on the occasion of a solar eclipse. For villagers, eclipses foretold bad tidings; they saw them as attempts by the dragon Rahu to swallow the sun and used clanging bells and fireworks to impel Rahu to disgorge it. Mongkut believed he could disabuse such fears if he could predict the event with mathematical calculations.

Invitations provided guests with the latitude and longitude of a spot on the Siamese coast where the eclipse would last longest. A mission of French astronomers journeyed more than 6,000 miles from Paris to witness the event. They were met by Mongkut's entourage, including members of the royal family, retainers, skeptical court astrologers, horses, oxen and 50 elephants.

On the appointed morning, August 18, 1868, at the exact second indicated by the king's calculations, the sky went totally dark, a remarkable feat of prediction. Mongkut and his prime minister cried "Hurrah! Hurrah!" The exhausted French astronomers acknowledged his accuracy; court astrologers were nonplussed. But skeptics soon claimed justification for their fears and superstitions; in a matter of days, the king and several others in the royal party fell ill with malaria contracted on the marshy shore.

In October, an ailing Mongkut gathered his advisers and urged them: "please go on with our good work in the interest of the people." Then he lay upon his right side and recited the sacred name of the lord Buddha to fix his mind firmly in the moment of his death.Like the Buddha himself, he died on his own birthday: October 18. Eight years later, his son, King Chulalongkorn, commissioned the bust now at the Smithsonian. It was to be a centerpiece of the Siamese exhibition at the U.S. Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876.