Karl Marx

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

Karl Marx—Political Philosopher

(1818-1883) May 5, 1818, Trier, Germany, 2:00 AM or 1:30 AM (Source: from M. Wemyss, “as recorded”; 2:00 AM from Famous Nativities; 1:30 from Sabian Symbols) Died, April 14, 1883, London, England

(Ascendant: Aquarius; MC, Sagittarius; Sun conjunct Moon Taurus; Venus also in Taurus; Mercury, Gemini; Uranus conjunct Neptune Sagittarius and also, loosely, to the MC; Mars, Cancer; Jupiter, Capricorn; Saturn and Pluto in Pisces)

The materialism and economic emphasis of Marx philosophy indicates the influence of his Taurean energy. Of all signs, Aquarius is the most communal (or communistic, if you will). The sharp conflict between the motifs of owning (Taurus) and group sharing (Aquarius) are clearly indicated.As a philosopher and political theorist emphasizing economics, the third ray is clearly indicated. This third ray presence is influenced by Jupiter, esoteric ruler of the Aquarian Ascendant in third ray Capricorn, and Mars in third ray Cancer. The third ray and Aquarius combine to render Marx an economic (third ray) revolutionary (Aquarius), as well as, essentially, a materialist (lower Taurus).

German philosopher and developer of the theory of socialism. Sutided law; became a newspaper editorl With Engels, presente The Communist Manifesto, (1847), Das Capital (1848). A dialectical materialist; helped found the Social Democratic Labor Party in 1869.

Communist, Philosopher, Dialectical Materialist, Writer.Leading philosopher of the nineteenth century, Marx wrote the Communist Manifesto in 1847 before being expelled from Brussels the following year.

All social rules and all relations between individuals are eroded by a cash economy, avarice drags Pluto himself out of the bowels of the earth.

(Sun, Moon, Venus & North Node in Taurus)Anyone who knows anything of history knows that great social changes are impossible without feminine upheaval. Social progress can be measured exactly by the social position of the fair sex, the ugly ones included.

Capitalist production, therefore, develops technology, and the combining together of various processes into a social whole, only by sapping the original sources of all wealth - the soil and the labourer.

Catch a man a fish, and you can sell it to him. Teach a man to fish, and you ruin a wonderful business opportunity.

(Sun, Moon & North Node in Taurus in 2nd house)Democracy is the road to socialism.

Experience praises the most happy the one who made the most people happy.

For the bureaucrat, the world is a mere object to be manipulated by him.

In a higher phase of communist society... only then can the narrow horizon of bourgeois right be fully left behind and society inscribe on its banners: from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.

In bourgeois society capital is independent and has individuality, while the living person is dependent and has no individuality.

Necessity is blind until it becomes conscious. Freedom is the consciousness of necessity.

(Uranus square Saturn & Pluto)Nothing can have value without being an object of utility.

(Venus in Taurus in 3rd house)Reason has always existed, but not always in a reasonable form.

Revolutions are the locomotives of history.

(Uranus in Sagittarius in 10th house)Society does not consist of individuals but expresses the sum of interrelations, the relations within which these individuals stand.

The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all nations into civilization.

The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e., the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force.

The meaning of peace is the absence of opposition to socialism.

The more the division of labor and the application of machinery extend, the more does competition extend among the workers, the more do their wages shrink together.

The oppressed are allowed once every few years to decide which particular representatives of the oppressing class are to represent and repress them.

The rich will do anything for the poor but get off their backs.

The writer may very well serve a movement of history as its mouthpiece, but he cannot of course create it.

Workers of the world unite; you have nothing to lose but your chains.

Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.

(Mercury in Gemini)

Karl Marx

Name: Karl Marx

Birth: May 5, 1818 (Trier, Germany)

Death: March 14, 1883 (London, England)

School/tradition: Marxism

Main interests: Politics, Economics, class struggleMarx was both a scholar and a political activist. Sometimes, he argued that his analysis of capitalism revealed that capitalism was destined to end because of unsolvable problems within capitalism:

The development of Modern Industry, therefore, cuts from under its feet the very foundation on which the bourgeoisie produces and appropriates products. What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable. [1]

Other times, he argued that capitalism would end through the organized actions of an international working class:Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things. The conditions of this movement result from the premises now in existence. (from The German Ideology)

While Marx was a relatively obscure figure in his own lifetime, his ideas began to exert a major influence on workers' movements shortly after his death. This influence was given added impetus by the victory of the Marxist Bolsheviks in the Russian October Revolution, and there are few parts of the world which were not significantly touched by Marxian ideas in the course of the twentieth century. The relation of Marx to "Marxism" is a point of controversy. While some argue that his ideas are discredited , Marxism is still very much influential in academic and political circles. Marxism continues to be the official ideology in some countries in the world such as North Korea. In his book "Marx's Das Capital" (2006), biographer Francis Wheen reiterates David McLellan's observation that since Marx's ideas had not triumphed in the West "..it had not been turned into an official ideology and is thus the object of serious study unimpeded by government controls.".Marx was born as the third child of seven children of a Jewish family in Trier, in the Rhineland region of Germany. His father Heinrich (1777-1838), who had descended from a long line of rabbis, converted to Christianity, despite his many deistic tendencies and his admiration of such Enlightenment figures as Voltaire and Rousseau. Marx's father was actually born Herschel Mordechai, but when the Prussian authorities would not allow him to continue practising law as a Jew, he joined the official denomination of the Prussian state, Lutheranism, which accorded him advantages, as one of a small minority of Lutherans in a predominantly Roman Catholic region. His mother was Henrietta (née Presborck; 1788-1863); his siblings were Sophie, Hermann, Henriette, Louise (m. Juta), Emilie and Caroline. The Marx household hosted many visiting intellectuals.

Education

Marx was educated at home until the age of thirteen. After graduating from the Trier Gymnasium, Marx enrolled in the University of Bonn in 1835 at the age of 17 to study law, where he joined the Trier Tavern Club drinking society and at one point served as its president; his grades suffered as a result. Marx was interested in studying philosophy and literature, but his father would not allow it because he did not believe that his son would be able to comfortably support himself in the future as a scholar. The following year, his father forced him to transfer to the far more serious and academically oriented Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin. During this period, Marx wrote many poems and essays concerning life, using the theological language acquired from his liberal, deistic father, such as "the Deity," but also absorbed the atheistic philosophy of the Young Hegelians who were prominent in Berlin at the time. Marx earned a doctorate in 1841 with a thesis titled The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature, but he had to submit his dissertation to the University of Jena as he was warned that his reputation among the faculty as a Young Hegelian radical would lead to a poor reception in Berlin.

The younger Karl Marx. Marx and the Young Hegelians

The Left, or Young Hegelians, consisted of a group of philosophers and journalists circling around Ludwig Feuerbach and Bruno Bauer opposing their teacher Hegel. Despite their criticism of Hegel's metaphysical assumptions, they made use of Hegel's dialectical method, separated from its theological content, as a powerful weapon for the critique of established religion and politics. Some members of this circle drew an analogy between post-Aristotelian philosophy and post-Hegelian philosophy. One of them, Max Stirner, turned critically against both Feuerbach and Bauer in his book "Der Einzige und sein Eigenthum" (1845, The Ego and Its Own), calling these atheists in all seriousness "pious people." Marx, at that time a follower of Feuerbach, was deeply impressed by the work and abandoned Feuerbachian materialism and accomplished what recent authors have denoted as an "epistemological break." He developed the basic concept of historical materialism against Stirner in his book "Die Deutsche Ideologie" (1846, The German Ideology), which he did not publish. [2] Another link to the Young Hegelians was Moses Hess, with whom Marx eventually disagreed, yet to whom he owed many of his insights into the relationship between state, society and religion.Towards the end of October 1843, Marx arrived in Paris, France. There, on August 28, 1844, at the Café de la Régence on the Place du Palais he began the most important friendship of his life, and one of the most important in history – he met Friedrich Engels. Engels had come to Paris specifically to see Marx, whom he had met only briefly at the office of the Rheinische Zeitung in 1842. [3] He came to show Marx what would turn out to be perhaps Engel's greatest work, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844.[4] Paris at this time was the home and headquarters to armies of German, British, Polish, and Italian revolutionaries. Marx, for his part, had come to Paris to work with Arnold Ruge, another revolutionary from Germany, on the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher .[5]

After the failure of the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, Marx, living on the rue Vaneau, wrote for the most radical of all German newspapers in Paris, indeed in Europe, the Vorwärts, established and run by the secret society called League of the Just. Marx's topics were generally on the Jewish question and Hegel. When not writing, Marx studied the history of the French Revolution and read Proudhon[6] He also spent considerable time studying a side of life he had never been acquainted with before -- a large urban proletariat.

[Hitherto exposed mainly to university towns...] Marx's sudden espousal of the proletarian cause can be directly attributed (as can that of other early German communists such as Weitling*) to his first hand contacts with socialists intellectuals [and books] in France.

*Author of the first book on communism in German, Humanity as it is and as it should be, published in Paris in 1838.[7]

He re-evaluated his relationship with Bauer and the Young Hegelians, and wrote On the Jewish Question, which was mostly a critique of current notions of civil rights and political emancipation, which also includes several critical references to Judaism as well as Christianity from an atheistic standpoint. Engels, a committed communist, kindled Marx's interest in the situation of the working class and guided Marx's interest in economics. Marx became a communist and set down his views in a series of writings known as the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, which remained unpublished until the 1930s. In the Manuscripts, Marx outlined a humanist conception of communism, influenced by the philosophy of Ludwig Feuerbach and based on a contrast between the alienated nature of labor under capitalism and a communist society in which human beings freely developed their nature in cooperative production.

In January 1845,after the Vorwärts expressed its hearty approval regarding the assassination attempt on the life of Frederick William IV, King of Prussia, Marx, among many others,were ordered to leave Paris. He and Engels moved on to Brussels, Belgium.

Marx devoted himself to an intensive study of history and elaborated on his idea of historical materialism, particularly in a manuscript (published posthumously as The German Ideology), the basic thesis of which was that "the nature of individuals depends on the material conditions determining their production." Marx traced the history of the various modes of production and predicted the collapse of the present one -- industrial capitalism -- and its replacement by communism. This was the first major work of what scholars consider to be his later phase, abandoning the Feuerbach-influenced humanism of his earlier work.

Next, Marx wrote The Poverty of Philosophy (1847), a response to Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's The Philosophy of Poverty and a critique of French socialist thought. These works laid the foundation for Marx and Engels' most famous work, The Communist Manifesto, first published on February 21, 1848, as the manifesto of the Communist League, a small group of European communists who had come to be influenced by Marx and Engels.

Later that year, Europe experienced tremendous revolutionary upheaval. Marx was arrested and expelled from Belgium; in the meantime a radical movement had seized power from King Louis Philippe in France, and invited Marx to return to Paris, where he witnessed the revolutionary June Insurrection (Revolutions of 1848 in France) first hand.

When this collapsed in 1849, Marx moved back to Cologne and started the Neue Rheinische Zeitung ("New Rhenish Newspaper"). During its existence he was put on trial twice, on February 7, 1849 because of a press misdemeanour, and on the 8th charged with incitement to armed rebellion. Both times he was acquitted. The paper was soon suppressed and Marx returned to Paris, but was forced out again. This time he sought refuge in London in May 1849 where he was to remain for the rest of his life.

London

In 1855, the Marx family suffered a blow with the death of their son, Edgar, from tuberculosis.[8] Meanwhile, Marx's major work on political economy made slow progress. By 1857 he had produced a gigantic 800 page manuscript on capital, landed property, wage labour, the state, foreign trade and the world market. This work however was not published until 1941, under the title Grundrisse. In the early 1860s he worked on composing three large volumes, Theories of Surplus Value, which discussed the theoreticians of political economy, particularly Adam Smith and David Ricardo. During this period, Marx championed the Union cause in the American Civil War. In 1867, well behind schedule, the first volume of Capital was published, a work which analyzed the capitalist process of production. Here, Marx elaborated his labor theory of value and his conception of surplus value and exploitation which he argued would ultimately lead to a falling rate of profit and the collapse of industrial capitalism. Volumes II and III remained mere manuscripts upon which Marx continued to work for the rest of his life and were published posthumously by Engels. In 1859, Marx was able to publish Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, his first serious economic work.One reason why Marx was so slow to publish Capital was that he was devoting his time and energy to the First International, to whose General Council he was elected at its inception in 1864. He was particularly active in preparing for the annual Congresses of the International and leading the struggle against the anarchist wing led by Mikhail Bakunin (1814-1876). Although Marx won this contest, the transfer of the seat of the General Council from London to New York in 1872, which Marx supported, led to the decline of the International. The most important political event during the existence of the International was the Paris Commune of 1871 when the citizens of Paris rebelled against their government and held the city for two months. On the bloody suppression of this rebellion, Marx wrote one of his most famous pamphlets, The Civil War in France, an enthusiastic defense of the Commune.

During the last decade of his life, Marx's health declined and he was incapable of the sustained effort that had characterized his previous work. He did manage to comment substantially on contemporary politics, particularly in Germany and Russia. In Germany, in his Critique of the Gotha Programme, he opposed the tendency of his followers Karl Liebknecht (1826-1900) and August Bebel (1840-1913) to compromise with the state socialism of Ferdinand Lassalle in the interests of a united socialist party. In his correspondence with Vera Zasulich, Marx contemplated the possibility of Russia's bypassing the capitalist stage of development and building communism on the basis of the common ownership of land characteristic of the village mir.

Family life

Marx in 1882.Karl Marx was married to Jenny von Westphalen, the educated daughter of a Prussian baron. Karl Marx's engagement to her was kept secret at first, and for several years was opposed by both the Marxes and Westphalens. Despite the objections, the two were married on June 19, 1843 in Kreuznacher Pauluskirche, Bad Kreuznach.During the first half of the 1850s the Marx family lived in poverty in a three room flat in the Soho quarter of London. Marx and Jenny already had four children and three more were to follow. Of these only three survived to adulthood. Marx's major source of income at this time was Engels, who was drawing a steadily increasing income from the family business in Manchester. This was supplemented by weekly articles written as a foreign correspondent for the New York Daily Tribune. Money from Engels allowed the family to move to somewhat more salubrious lodging in a new suburb on the then-outskirts of London. Marx generally lived a hand-to-mouth existence, forever at the limits of his resources, although this did extend to some spending on relatively bourgeois luxuries, which he felt were necessities for his wife and children given their social status and the mores of the time.

There is a disputed rumour that Marx was the father of Frederick Demuth, the son of Marx's housekeeper, Lenchen Demuth. It has been suggested that this rumour lacks any direct corroboration ([1]).

Marx's children by his wife were: Jenny Caroline (m. Longuet; 1844-1883); Jenny Laura (m. Lafargue; 1846-1911); Edgar (1847-1855); Henry Edward Guy ("Guido"; 1849-1850); Jenny Eveline Frances ("Franziska"; 1851-1852); Jenny Julia Eleanor (1855-1898); and one more who died before being named (July 1857).

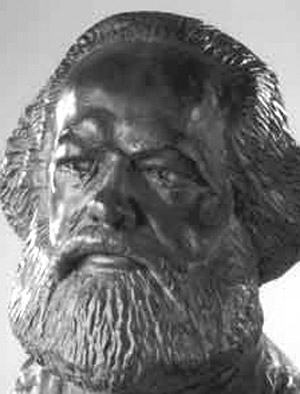

Tomb in London. Death and Legacy

Following the death of his wife Jenny in 1881, Marx developed a catarrh that kept him in ill health for the last two years of his life and eventually brought on the bronchitis and pleurisy that killed him. He died on March 14, 1883, as a stateless person.[9] He was buried in Highgate Cemetery, London, on 17 March 1883. The message carved on Marx's tombstone is: "WORKERS OF ALL LANDS, UNITE", the final line of The Communist Manifesto. The tombstone was a monument built in 1954 by the Communist Party of Great Britain with a portrait bust by Laurence Bradshaw — Marx's original tomb was humbly adorned; only eleven people were present at his funeral[10]. In 1970, there was an unsuccessful attempt to blow up the monument [2].Several of Marx's closest friends spoke at his funeral, including Karl Liebknecht and Friedrich Engels. Engels' speech included the words:

"On the 14th of March, at a quarter to three in the afternoon, the greatest living thinker ceased to think. He had been left alone for scarcely two minutes, and when we came back we found him in his armchair, peacefully gone to sleep-but forever." [3]

Marx's daughter Eleanor became a socialist like her father and helped edit his works.Marx's thought

The American Marx scholar Hal Draper once remarked, "there are few thinkers in modern history whose thought has been so badly misrepresented, by Marxists and anti-Marxists alike." The legacy of Marx's thought is bitterly contested between numerous tendencies who claim to be Marx's most accurate interpreters, including Marxist-Leninism, Trotskyism, Maoism, and libertarian Marxism.Philosophy

Marx's philosophy hinges on his view of human nature. Along with the Hegelian dialectic, Marx inherited a disdain for the notion of an underlying invariant human nature. Sometimes Marxists express their views by contrasting “nature” with “history”. Sometimes they use the phrase “existence precedes consciousness”. The point, in either case, is that who a person is, is determined by where and when he is — social context takes precedence over innate behavior; or, in other words, one of the main features of human nature is adaptability. Nevertheless, Marxian thought rests on the fundamental assumption that it is human nature to transform nature, and he calls this process of transformation "labour " and the capacity to transform nature labour power. For Marx, this is a natural capacity for a physical activity, but it is intimately tied to the active role of human consciousness:“ A spider conducts operations that resemble those of a weaver, and a bee puts to shame many an architect in the construction of her cells. But what distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality. ”

— (Capital, Vol. I, Chap. 7, Pt. 1)Marx did not believe that all people worked the same way, or that how one works is entirely personal and individual. Instead, he argued that work is a social activity and that the conditions and forms under and through which people work are socially determined and change over time.

Marx's analysis of history is based on his distinction between the means / forces of production, literally those things, such as land, natural resources, and technology, that are necessary for the production of material goods, and the relations of production, in other words, the social and technical relationships people enter into as they acquire and use the means of production. Together these comprise the mode of production; Marx observed that within any given society the mode of production changes, and that European societies had progressed from a feudal mode of production to a capitalist mode of production. In general, Marx believed that the means of production change more rapidly than the relations of production (for example, we develop a new technology, such as the Internet, and only later do we develop laws to regulate that technology). For Marx this mismatch between (economic) base and (social) superstructure is a major source of social disruption and conflict.

Marx understood the "social relations of production" to comprise not only relations among individuals, but between or among groups of people, or classes. As a scientist and materialist, Marx did not understand classes as purely subjective (in other words, groups of people who consciously identified with one another). He sought to define classes in terms of objective criteria, such as their access to resources. For Marx, different classes have divergent interests, which is another source of social disruption and conflict. Conflict between social classes being something which is inherent in all human history:

"The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles." (The Communist Manifesto, Chapter 1.)

Marx was especially concerned with how people relate to that most fundamental resource of all, their own labour power. Marx wrote extensively about this in terms of the problem of alienation. As with the dialectic, Marx began with a Hegelian notion of alienation but developed a more materialist conception. For Marx, the possibility that one may give up ownership of one's own labour — one's capacity to transform the world — is tantamount to being alienated from one's own nature; it is a spiritual loss. Marx described this loss in terms of commodity fetishism, in which the things that people produce, commodities, appear to have a life and movement of their own to which humans and their behavior merely adapt. This disguises the fact that the exchange and circulation of commodities really are the product and reflection of social relationships among people. Under capitalism, social relationships of production, such as among workers or between workers and capitalists, are mediated through commodities, including labor, that are bought and sold on the market.Commodity fetishism is an example of what Engels called false consciousness, which is closely related to the understanding of ideology. By ideology they meant ideas that reflect the interests of a particular class at a particular time in history, but which are presented as universal and eternal. Marx and Engels' point was not only that such beliefs are at best half-truths; they serve an important political function. Put another way, the control that one class exercises over the means of production includes not only the production of food or manufactured goods; it includes the production of ideas as well (this provides one possible explanation for why members of a subordinate class may hold ideas contrary to their own interests). Thus, while such ideas may be false, they also reveal in coded form some truth about political relations. For example, although the belief that the things people produce are actually more productive than the people who produce them is literally absurd, it does reflect the fact (according to Marx and Engels) that people under capitalism are alienated from their own labour-power. Another example of this sort of analysis is Marx's understanding of religion, summed up in a passage from the preface to his 1843 Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right:

“ Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sign of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people. ”

Whereas his Gymnasium senior thesis argued that the primary social function of religion was to promote solidarity, here Marx sees the social function as a way of expressing and coping with social inequality, thereby maintaining the status quo.

Political economy

Marx argued that this alienation of human work (and resulting commodity fetishism) is precisely the defining feature of capitalism. Prior to capitalism, markets existed in Europe where producers and merchants bought and sold commodities. According to Marx, a capitalist mode of production developed in Europe when labor itself became a commodity — when peasants became free to sell their own labor-power, and needed to do so because they no longer possessed their own land. People sell their labor-power when they accept compensation in return for whatever work they do in a given period of time (in other words, they are not selling the product of their labor, but their capacity to work). In return for selling their labor power they receive money, which allows them to survive. Those who must sell their labor power are "proletarians." The person who buys the labor power, generally someone who does own the land and technology to produce, is a "capitalist" or "bourgeoisie." The proletarians inevitably outnumber the capitalists.Marx distinguished industrial capitalists from merchant capitalists. Merchants buy goods in one market and sell them in another. Since the laws of supply and demand operate within given markets, there is often a difference between the price of a commodity in one market and another. Merchants, then, practice arbitrage, and hope to capture the difference between these two markets. According to Marx, capitalists, on the other hand, take advantage of the difference between the labor market and the market for whatever commodity is produced by the capitalist. Marx observed that in practically every successful industry input unit-costs are lower than output unit-prices. Marx called the difference "surplus value" and argued that this surplus value had its source in surplus labour, the difference between what it costs to keep workers alive and what they can produce.

The capitalist mode of production is capable of tremendous growth because the capitalist can, and has an incentive to, reinvest profits in new technologies. Marx considered the capitalist class to be the most revolutionary in history, because it constantly revolutionized the means of production. But Marx argued that capitalism was prone to periodic crises. He suggested that over time, capitalists would invest more and more in new technologies, and less and less in labor. Since Marx believed that surplus value appropriated from labor is the source of profits, he concluded that the rate of profit would fall even as the economy grew. When the rate of profit falls below a certain point, the result would be a recession or depression in which certain sectors of the economy would collapse. Marx understood that during such a crisis the price of labor would also fall, and eventually make possible the investment in new technologies and the growth of new sectors of the economy.

Marx believed that this cycle of growth, collapse, and growth would be punctuated by increasingly severe crises. Moreover, he believed that the long-term consequence of this process was necessarily the enrichment and empowerment of the capitalist class and the impoverishment of the proletariat. He believed that were the proletariat to seize the means of production, they would encourage social relations that would benefit everyone equally, and a system of production less vulnerable to periodic crises. In general, Marx thought that peaceful negotiation of this problem was impracticable, and that a massive, well-organized and violent revolution would in general be required, because the ruling class would not give up power without violence. He theorized that to establish the socialist system, a dictatorship of the proletariat - a period where the needs of the working-class, not of capital, will be the common deciding factor - must be created on a temporary basis. As he wrote in his "Critique of the Gotha Program", "between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat." [4] Yet he was aware of the possibility that in some countries, with strong democratic institutional structures (e.g. Britain, the US and the Netherlands) this transformation could occur through peaceful means, while in countries with a strong centralized state-oriented traditions, like France and Germany, the upheaval will have to be violent.

(1818-1883) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Karl Marx, the son of Hirschel and Henrietta Marx, was born in Trier, Germany, in 1818. Hirschel Marx was a lawyer and to escape anti-Semitism decided to abandon his Jewish faith when Karl was a child. Although the majority of people living in Trier were Catholics, Marx decided to become a Protestant. He also changed his name from Hirschel to Heinrich.

After schooling in Trier (1830-35), Marx entered Bonn University to study law. At university he spent much of his time socializing and running up large debts. His father was horrified when he discovered that Karl had been wounded in a duel. Heinrich Marx agreed to pay off his son's debts but insisted that he moved to the more sedate Berlin University.

The move to Berlin resulted in a change in Marx and for the next few years he worked hard at his studies. Marx came under the influence of one of his lecturers, Bruno Bauer, whose atheism and radical political opinions got him into trouble with the authorities. Bauer introduced Marx to the writings of G. W. F. Hegel, who had been the professor of philosophy at Berlin until his death in 1831.

Marx was especially impressed by Hegel's theory that a thing or thought could not be separated from its opposite. For example, the slave could not exist without the master, and vice versa. Hegel argued that unity would eventually be achieved by the equalizing of all opposites, by means of the dialectic (logical progression) of thesis, antithesis and synthesis. This was Hegel's theory of the evolving process of history.

Heinrich Marx died in 1838. Marx now had to earn his own living and he decided to become a university lecturer. After completing his doctoral thesis at the University of Jena, Marx hoped that his mentor, Bruno Bauer, would help find him a teaching post. However, in 1842 Bauer was dismissed as a result of his outspoken atheism and was unable to help.

Marx now tried journalism but his radical political views meant that most editors were unwilling to publish his articles. He moved to Cologne where the city's liberal opposition movement was fairly strong. Known as the Cologne Circle, this liberal group had its own newspaper, The Rhenish Gazette. The newspaper published an article by Marx where he defended the freedom of the press. The group was impressed by the article and in October, 1842, Marx was appointed editor of the newspaper.

In Cologne Karl Marx met Moses Hess, a radical who called himself a socialist. Marx began attending socialist meetings organized by Hess. Members of the group told Marx of the sufferings being endured by the German working-class and explained how they believed that only socialism could bring this to an end. Based on what he heard at these meetings, Marx decided to write an article on the poverty of the Mosel wine-farmers. The article was also critical of the government and soon after it was published in the Rhenish Gazette in January 1843, the newspaper was banned by the Prussian authorities.

Warned that he might be arrested Marx quickly married his girlfriend, Jenny von Westphalen, and moved to Paris where he was offered the post of editor of a new political journal, Franco-German Annals. Among the contributors to the journal was his old mentor, Bruno Bauer, the Russian anarchist, Michael Bakunin and the radical son of a wealthy German industrialist, Friedrich Engels.

In Paris Marx began mixing with members of the working class for the first time. Marx was shocked by their poverty but impressed by their sense of comradeship. In an article that he wrote for the Franco-German Annals, Marx applied Hegel's dialectic theory to what he had observed in Paris. Marx, who now described himself as a communist, argued that the working class (the proletariat), would eventually be the emancipators of society. When published in February 1844, the journal was immediately banned in Germany. Marx also upset the owner of the journal, Arnold Ruge, who objected to his editor's attack on capitalism.

Marx had now become a close friend of Friedrich Engels, who had just finished writing a book about the lives of the industrial workers in England. Engels shared Marx's views on capitalism and after their first meeting Engels wrote that there was virtually "complete agreement in all theoretical fields". Marx and Engels decided to work together. It was a good partnership, whereas Marx was at his best when dealing with difficult abstract concepts, Engels had the ability to write for a mass audience.

While working on their first article together, The Holy Family, the Prussian authorities put pressure on the French government to expel Marx from the country. On 25th January 1845, Marx received an order deporting him from France. Marx and Engels decided to move to Belgium, a country that permitted greater freedom of expression than any other European state. Marx went to live in Brussels, where there was a sizable community of political exiles, including the man who converted him to socialism, Moses Hess.

Friedrich Engels helped to financially support Marx and his family. Engels gave Marx the royalties of his recently published book, Condition of the Working Class in England and arranged for other sympathizers to make donations. This enabled Marx the time to study and develop his economic and political theories. Marx spent his time trying to understand the workings of capitalist society, the factors governing the process of history and how the proletariat could help bring about a socialist revolution. Unlike previous philosophers, Marx was not only interested in discovering the truth. As he was to write later, in the past "philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is, to change it".

In July 1845 Marx and Engels visited England. They spent most of the time consulting books in Manchester Library. Marx also visited London where he met the Chartist leader, George Julian Harney and political exiles from Europe.

When Karl Marx returned to Brussels he concentrated on finishing his book, The German Ideology. In the book Marx developed his materialist conception of history, a theory of history in which human activity, rather than thought, plays the crucial role. Marx was unable to find a publisher for the book, and like much of his work, was not published in his lifetime.

In January 1846 Marx set up a Communist Correspondence Committee. The plan was to try and link together socialist leaders living in different parts of Europe. Influenced by Marx's ideas, socialists in England held a conference in London where they formed a new organization called the Communist League. Marx formed a branch in Brussels and in December 1847 attended a meeting of the Communist League' Central Committee in London. At the meeting it was decided that the aims of the organization was "the overthrow of the bourgeoisie, the domination of the proletariat, the abolition of the old bourgeois society based on class antagonisms, and the establishment of a new society without classes and without private property".

When Marx returned to Brussels had concentrated on writing The Communist Manifesto. Based on a first draft produced by Friedrich Engels called the Principles of Communism, Marx finished the 12,000 word pamphlet in six weeks. Unlike most of Marx's work, it was an accessible account of communist ideology. Written for a mass audience, The Communist Manifesto summarized the forthcoming revolution and the nature of the communist society that would be established by the proletariat.

The Communist Manifesto was published in February, 1848. The following month, the government expelled Marx from Belgium. Marx and Engels visited Paris before moving to Cologne where they founded a radical newspaper, New Rhenish Gazette. The men hoped to use the newspaper to encourage the revolutionary atmosphere that they had witnessed in Paris.

After examples of police brutality in Cologne, Marx helped establish a Committee of Public Safety to protect the people against the power of the authorities. The New Rhenish Gazette continued to publish reports of revolutionary activity all over Europe, including the Democrats seizure of power in Austria and the decision by the Emperor to flee the country.

Marx's excitement about the possibility of world revolution began to subside in 1849. The army had managed to help the Emperor of Austria return to power and attempts at uprisings in Dresden, Baden and the Rhur were quickly put down. On 9th May, 1849, Marx received news he was to be expelled from the country. The last edition of the New Rhenish Gazette appeared on 18th May and was printed in red. Marx wrote that although he was being forced to leave, his ideas would continue to be spread until the "emancipation of the working class".

Marx now went to Paris where he believed a socialist revolution was likely to take place at any time. However, within a month of arriving, the French police ordered him out of the capital. Only one country remained who would take him, and on 15th September he sailed for England. Soon after settling in London Jenny Marx gave birth to her fourth child. The Prussian authorities applied pressure on the British government to expel Marx but the Prime Minister, John Russell, held liberal views on freedom of expression and refused.

With only the money that Engels could raise, the Marx family lived in extreme poverty. In March 1850 they were ejected from their two-roomed flat in Chelsea for failing to pay the rent. They found cheaper accommodation at 28 Dean Street, Soho, where they stayed for six years. Their fifth child, Franziska, was born at their new flat but she only lived for a year. Eleanor was born in 1855 but later that year, Edgar became Jenny Marx's third child to die.

Marx spent most of the time in the Reading Room of the British Museum, where he read the back numbers of The Economist and other books and journals that would help him analyze capitalist society. In order to help supply Marx with an income, Friedrich Engels returned to work for his father in Germany. The two kept in constant contact and over the next twenty years they wrote to each other on average once every two days.

Friedrich Engels sent postal orders or £1 or £5 notes, cut in half and sent in separate envelopes. In this way the Marx family was able to survive. The poverty of the Marx's family was confirmed by a Prussian police agent who visited the Dean Street flat in 1852. In his report he pointed out that the family had sold most of their possessions and that they did not own one "solid piece of furniture".

Jenny helped her husband with his work and later wrote that "the memory of the days I spent in his little study copying his scrawled articles is among the happiest of my life." The only relief from the misery of poverty was on a Sunday when they went for family picnics on Hampstead Heath.

In 1852, Charles Dana, the socialist editor of the New York Daily Tribune, offered Marx the opportunity to write for his newspaper. Over the next ten years the newspaper published 487 articles by Marx (125 of them had actually been written by Engels). Another radical in the USA, George Ripley, commissioned Marx to write for the New American Cyclopaedia. With the money from Marx's journalism and the £120 inherited from Jenny's mother, the family were able to move to 9 Grafton Terrace, Kentish Town.

In 1856 Jenny Marx, who was now aged 42, gave birth to a still-born child. Her health took a further blow when she contacted smallpox. Although she survived this serious illness, it left her deaf and badly scarred. Marx's health was also bad and he wrote to Engels claiming that "such a lousy life is not worth living". After a bad bout of boils in 1863 Marx told Engels that the only consolation was that "it was a truly proletarian disease".

By the 1860s the work for the New York Daily Tribune came to an end and Marx's money problems returned. Engels sent him £5 a month but this failed to stop him getting deeply into debt. Ferdinand Lassalle, a wealthy socialist from Berlin also began sending money to Marx and offered him work as an editor of a planned new radical newspaper in Germany. Marx, unwilling to return to his homeland and rejected the job. Lassalle continued to send Marx money until he was killed in a duel on 28th August 1864.

Despite all his problems Marx continued to work and in 1867 the first volume of Das Kapital was published. A detailed analysis of capitalism, the book dealt with important concepts such as surplus value (the notion that a worker receives only the exchange-value, not the use-value, of his labour); division of labour (where workers become a "mere appendage of the machine") and the industrial reserve army (the theory that capitalism creates unemployment as a means of keeping the workers in check).

In the final part of Das Kapital Marx deals with the issue of revolution. Marx argued that the laws of capitalism will bring about its destruction. Capitalist competition will lead to a diminishing number of monopoly capitalists, while at the same time, the misery and oppression of the proletariat would increase. Marx claimed that as a class, the proletariat will gradually become "disciplined, united and organised by the very mechanism of the process of capitalist production" and eventually will overthrow the system that is the cause of their suffering.

Marx now began work on the second volume of Das Kapital. By 1871 his sixteen year old daughter, Eleanor Marx, was helping him with his work. Taught at home by her father, Eleanor already had a detailed understanding of the capitalist system and was to play an important role in the future of the British labor movement. On one occasion Marx told his children that "Jenny (his eldest daughter) is most like me, but Tussy (Eleanor) is me."

Marx was encouraged by the formation of the Paris Commune in March 1871 and the abdication of Louis Napoleon. Marx called it the "greatest achievement" since the revolutions of 1848, but by May the revolt had collapsed and about 30,000 Communards were slaughtered by government troops.

This failure depressed Marx and after this date his energy began to diminish. He continued to work on the second volume of Das Kapital but progress was slow, especially after Eleanor Marx left home to become a schoolteacher in Brighton.

Eleanor returned to the family home in 1881 to nurse her parents who were both very ill. Marx, who had a swollen liver, survived, but Jenny Marx died on 2nd December, 1881. Karl Marx was also devastated by the death of his eldest daughter in January 1883 from cancer of the bladder. Karl Marx died two months later on the 14th March, 1883.