Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

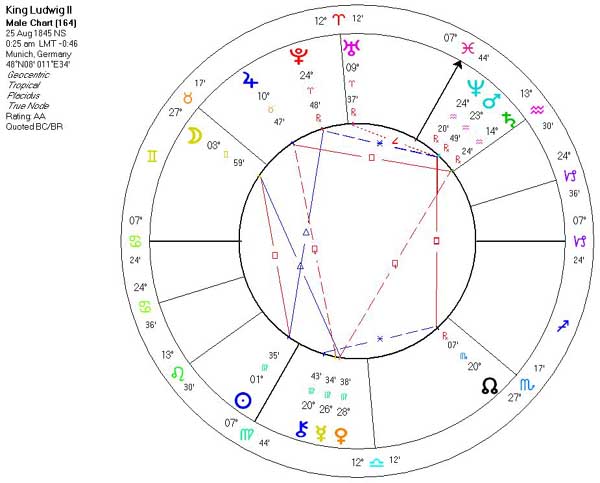

King Ludwig II

Reign 10 March 1864-13 June 1886

Born 25 August 1845

Died 13 June 1886

Ludwig (Louis) II, King of Bavaria, Ludwig Friedrich Wilhelm; sometimes known in English as "Mad King Ludwig" and as the "Märchenkönig" (Fairy-tale King) in German. (August 25, 1845 – June 13, 1886) was king of Bavaria from 1864 until his death.

King Ludwig II designed and built the Bavarian castle Neuschwanstein, which inspired the design of the Sleeping Beauty Castle at Disneyland; he left a large collection of plans for other castles that were never built.

Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria with his brother Otto in 1858Born in Nymphenburg (today part of Munich), he was the son of King Maximilian II of Bavaria and Princess Marie of Prussia. Ludwig was continually reminded of his royal power as a child, and as a child he was extremely spoiled on some occasions but severely controlled by his instructors and subjected to a strict regimen of study and exercise on others. Ludwig apologists explain that much of his odd behaviour as an adult was caused by the stress of growing up in a royal family.

Ludwig's youth did have happy times, such as visits to Hohenschwangau and Lake Starnberg with his family. Teenaged Ludwig became best friends and possibly the lover of his aide de camp, the handsome aristocrat and actor Paul Maximilian Lamoral of Thurn and Taxis of Bavaria's wealthy Thurn and Taxis family. The two young men rode together, read poetry aloud, and staged scenes from the Romantic operas of Richard Wagner. The relationship broke off when Paul became more interested in young women. During his youth, Ludwig also initiated a lifelong friendship with his cousin Duchess Elisabeth, Empress of Austria. They both loved nature and poetry, and nicknamed each other "the Eagle" (Ludwig) and "the Seagull" (Elisabeth).

Ludwig II of BavariaLudwig ascended to the Bavarian throne at age 18, following his father's death. His youth and brooding good looks made him wildly popular in Bavaria and abroad. One of his first acts was official patronage of his idol, the German opera composer Richard Wagner, despite Wagner having Europe-wide notoriety for his past political activism and radical new-style operas. Wagner's Lohengrin, with its swan knight hero and focus on medieval German romance, had captivated the young king's fantasy-filled imagination, and he even invited the radical composer to his conservative-minded royal court.

The greatest stresses of Ludwig's early reign were pressure to produce an heir, and relations with militant Prussia. Both issues came to the forefront in 1867. Ludwig was engaged to Princess Sophie, his cousin and Empress Elisabeth's younger sister. Their engagement was publicized on January 22, 1867, but after repeatedly postponing the wedding date, Ludwig finally cancelled the engagement in October. Ludwig never married, but Sophie later married Ferdinand Philippe Marie, duc d'Alençon (1844–1910), son of Louis Charles Philippe Raphael, duc de Nemours. She died several years later in a fire which destroyed the Paris Charity Bazaar.

Though Ludwig had sided with Austria against Prussia in the Seven Weeks' War, he accepted a mutual defense treaty with Prussia in 1867 after being defeated in the war. Under the terms of this treaty, Bavaria joined with Prussia against France in the Franco-Prussian War. On the request of Bismarck, Ludwig solicited a letter in December 1870 calling for the creation of a German Empire. He received some concessions in return for his support, but the era of Bavarian independence was over.

Throughout his reign, Ludwig had a succession of infatuations with handsome men, including his chief equerry Richard Hornig, Hungarian theatre star Josef Kainz, and courtier Alfons Weber. In 1869, he began keeping a diary in which he recorded his private thoughts and discussed his attempts to suppress his sexual desires and remain true to his Catholic beliefs. Ludwig's original diaries were lost during World War II, and all that remains today are copies of entries made prior to the war. These copied diary entries, along with private letters and other surviving personal documents, suggest that Ludwig struggled with homosexuality.[1]

As Ludwig's rule progressed, he became increasingly withdrawn. In the 1880s, Ludwig spent much of his time in seclusion in the Alps. There he built several expensive fairytale palaces with the stage designer Christian Jank, and imagined a dream world with himself as an absolute monarch descended from Louis XIV of France.

[edit] His death

Ludwig II of BavariaOn June 10, 1886, Ludwig was officially declared insane by the government and incapable of executing his governmental powers, and Prince Luitpold was declared regent. The psychiatrist Professor Bernhard von Gudden despite never having examined Ludwig, headed the psychiatric team that declared Ludwig to be suffering from paranoia (comparable to a modern diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia). Their chief evidence was stories of Ludwig's odd behavior, collected from palace servants by his political enemies. As many of these stories were not firsthand accounts and may have been obtained with bribery or threats, their reliability is questionable. Some historians believe that Ludwig was sane, an innocent victim of political intrigue. Others believe he may have suffered from a substance abuse problem or neurological disorder rather than mental illness. Empress Elisabeth held that "The King was not mad; he was just an eccentric living in a world of dreams. They might have treated him more gently, and thus perhaps spared him so terrible an end."Ludwig was taken into custody in secret. The event proved as unusual as any in his life. An eccentric but loyal baroness arrived at the gate of the rural castle to wave her umbrella menacingly and to harangue the men who came to imprison Ludwig. The king himself reportedly ordered all kinds of nonsensical punishments against the "treasonous" ministers. A huge force of peasants swarmed to Hohenschwangau to protect the King. They were willing to escort Ludwig under guard across the border to save him. But Ludwig refused. The battalion of soldiers at nearby Kempten had been summoned to Neuschwanstein, but it was retained by the government.

Ludwig attempted to issue the following proclamation to the public:

The Prince Luitpold intends, against my will, to ascend to the Regency of my land, and my erstwhile ministry has, through false allegations regarding the state of my health, deceived my beloved people, and is preparing to commit acts of high treason. [...] I call upon every loyal Bavarian to rally around my loyal supporters to thwart the planned treason against the King and the fatherland.

This was printed by a Bamberg newspaper on June 11, 1886, but the copies were seized by the government to prevent distribution. Most of Ludwig's telegrams to the newspapers and his friends were intercepted. Ludwig did receive a message from Bismarck advising him to go to Munich and show himself to the people, but Ludwig refused to leave Neuschwanstein. On the morning of the twelfth, a second Commission reached the castle. The King was placed under arrest at 4:00 a.m. and transported to Castle Berg in Berg, south of Munich.Mystery surrounds Ludwig's death on Lake Starnberg (then called Lake Würm). On June 13, at 6:30 p.m., Ludwig asked to take a walk with Professor Gudden. Gudden agreed, and told the guards not to follow them. The two men never returned from their walk. King Ludwig and Professor Gudden were found dead in the water near the shore of Lake Starnberg at 11:30 p.m. that night. A little chapel was later built overlooking the site. A remembrance ceremony is held there each year on June 13.

Ludwig's death was officially ruled a suicide by drowning, but alternate theories abound. Ludwig was known to be a good swimmer, the water was less than waist-deep where his body was found, and the official autopsy report indicates that no water was found in his lungs. No solid proof of foul play has ever come to light, but many hold that Ludwig was either assassinated by his political enemies or killed while attempting to escape from Berg. Another theory suggests that Ludwig died of natural causes (such as a heart attack or stroke) during an escape attempt.

Ludwig's body was interred in the crypt of the Michaelskirche in Munich. His heart, however, does not lie with the rest of his body. Bavarian tradition called for the heart of the king to be placed in a silver urn and sent to the Gnadenkapelle (Chapel of the Miraculous Image) in Altötting. Ludwig's urn sits beside those of his father and grandfather inside the shrine.

His legacy

Ludwig is remembered as one of the most unusual rulers in German history. He was quite popular among his subjects, for three major reasons. First, he avoided engaging in war, giving Bavaria a time of peace. Whether this was due to a belief in pacifism or a lack of interest in politics is debatable. Second, Ludwig funded the construction of his famous fairy-tale castles with his personal income, not from the state budget. This gave many people employment and brought a considerable flow of money to the regions involved. Third, his public eccentricities could be very charming. He hated crowds and formal affairs, but Ludwig did not consider himself above socializing with commoners. He enjoyed traveling in the Bavarian countryside and chatting with farmers and labourers he met along the way. Ludwig also delighted in rewarding those who were hospitable to him during his travels with lavish gifts. He is still remembered in Bavaria as "Unser Kini" which means "our darling king" in the Bavarian dialect of German.Ironically, although their construction nearly bankrupted Bavaria's royal family, Ludwig's palaces have become profitable tourist attractions for the Bavarian state. The palaces have paid for themselves many times over.

] Ludwig and the arts

Ludwig II with his idol Richard Wagner, the composer of Lohengrin, at the piano

An 1890s photochrom print of Neuschwanstein.

The coat of arms of King Ludwig over the entrance to Neuschwanstein.Ludwig was a major patron of composer Richard Wagner, and he funded the construction of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus. Without Ludwig's support, it is almost certain that Wagner would have been unable to complete his opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen or to write his final opera, Parsifal. Ludwig also sponsored the premieres of Tristan und Isolde, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and, through his financial support of the Bayreuth Festival, those of Der Ring des Nibelungen and Parsifal.

[edit] His buildings

Ludwig left behind a large collection of plans and designs for other castles that were never built, as well as plans for further rooms in his completed buildings. Many of these designs are housed today in the King Ludwig II Museum at Herrenchiemsee. These building designs date from the latter part of the King's reign, beginning around 1883. As money was starting to run out, the artists knew that their designs would never be executed. The designs became more extravagant and numerous as the artists realized that there was no need to concern themselves with economy or practicality.NeuschwansteinNeuschwanstein—or "New Swan Stone", a dramatic Romanesque fortress with Byzantine and Gothic interiors, which was built next to his father's castle: Hohenschwangau. Numerous wall paintings depict scenes from Wagner's operas. Christian glory and chaste love figure predominantly in the iconography, and may have been intended to help Ludwig live up to his religious ideals. The castle was not finished at Ludwig's death. It is by far the best known (to non-Germans) landmark in Germany today. Neuschwanstein would become the inspiration for the Sleeping Beauty Castle at Disneyland.

Linderhof—an ornate palace in neo-Rococo style, with handsome formal gardens. The grounds contain a grotto where opera singers performed on an underground lake lit with electricity, a novelty at that time, and a Romantic woodsman's hut built inside an artificial tree. Inside the palace, iconography reflects Ludwig's fascination with the absolutist government of Ancien Régime France. Ludwig saw himself as the "Moon King", a Romantic shadow of the earlier "Sun King", Louis XIV of France. From Linderhof, Ludwig enjoyed moonlit sleigh rides in an elaborate eighteenth century sleigh, complete with footmen in eighteenth century livery. He was known to stop and visit with rural peasants while on rides, adding to his legend and popularity.

Herrenchiemsee—a replica of the palace at Versailles, France, which was meant to outdo its predecessor in scale and opulence. It is located on an island in the middle of the Chiemsee. Most of the palace was never completed once the king ran out of money, and Ludwig lived there for only the 10 days before his mysterious death.

Ludwig also outfitted Schachen king's house with an overwhelmingly decorative Arabian style interior, including a replica of the famous Peacock Throne. There are stories of luxurious parties with the king sometimes reclining in the role of Turkish sultan while the most handsome soldiers and stable boys served him as scantily clad dancers. These stories may or may not be true.

Falkenstein—a planned, but never executed "robber baron's castle". A painting by Christian Jank shows the proposed building as an even more fairytale version of Neuschwanstein, perched on a rocky cliff.

v • d • eLudwig II of Bavaria's buildings

Falkenstein | Herrenchiemsee | Königshaus am Schachen | Linderhof | Neuschwanstein

The Story of King Ludwig II of Bavaria

Birth of a fairy tale king

On August 25, 1845, the first son of Maximillian Crown Prince of Bavaria and Marie of Prussia was born in the Nymphenburg Castle outside of Munich. Although the child's royal christening medal originally read Otto Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig, King Ludwig I forced the parents to change his grandson's name. In his opinion, renaming the child Ludwig was a fitting tribute - after all, the prince's birthday was on Saint Ludwig's day, and also fell on the same day as his grandfather's. On November 15, 1845 Ludwig I published a decree stating that the Bavarian prince’s oldest son would henceforth be called Erbprinz (inheriting prince) in order to distinguish him from the other princes of the royal house. And so, Ludwig made history for the first time at the age of three months by becoming the very first Bavarian Erbprinz. His official title would change once more when King Ludwig I resigned in March of 1848 under political pressure. His son Maximilian became King Maximillian II, and three-year-old Ludwig was officially named Bavaria's new crown prince.

Childhood and youth

As was common at the time, Ludwig's early upbringing fell into the hands of a governess, Miss Maria Katharina Theresia Sybille Meilhaus, and the young prince came to adore her deeply. Sybille encouraged Ludwig's imaginative mind, and he thrived under her tutelage. She was well-respected in the small mountain community and thought to be a “…lady displaying comprehensive education, deep religiousness and a rare kind-heartedness,” according to her obituary in the Augsburg Postzeitung.

Despite Ludwig's intimate bond with Sybille, a strict male educator named Count La Rosée was given charge of Ludwig's upbringing when the young dreamer was only 7 years old. As could be expected, the crown prince's interests in poetry and music were quickly smothered in an attempt to prepare him for the political and economic rigors of his future responsibilities. Although the child's sadness at this turn of events did not go unnoticed by the family, the decision remained firm.

By most accounts, Ludwig was an isolated and solitary child whose only real companions were his younger brother Otto and cousins Sisi and Sophie. His favorite hobbies continued to revolve around the arts, and between 1858 and 1860 Ludwig received piano lessons three times a week. Unfortunately, the prince's passion did not translate into ability and the lessons were eventually cancelled at the delight of his frustrated piano teacher. Ludwig's love for literature also came early in his life, and by the age of twelve he was already immersing himself into Richard Wagner’s complex prose. Lost in the words of his favorite author, perhaps Ludwig felt that his childhood dreams could actually become true through the means of art and theater.

At the age of eleven, Ludwig began to receive 21 Marks of spending money per month, which he was obligated to account for in a bankbook. This document reavealed that the Crown Prince was very accurate with this task until his accession to the throne in March 1864, despite spending most of his money on presents for others (a tendency that continued throughout his life and, some say, eventually contributed to his financial troubles). Ludwig finally had his first opportunity to see Richard Wagner’s opera Tannhäuser at the age of 16, an experience that thrilled and enchanted the young man. By then, his great respect and admiration for Richard Wagner had almost become an obsession. A few years later the Crown Prince started attending Munich University, studying French, philosophy, physics, chemistry, and - to his disdain -"the art of war”. On his 18th birthday, Ludwig was given more independence: his spending money was increased to 50 Marks monthly, and he was also assigned his own apartment in the residence. He has no idea that in less that a year he would become King.

Ludwig becomes King

King Maximilian II died unexpectedly on March 10, 1864 after a brief period of illness. Ludwig was devastated, but nonetheless proclaimed King on the very same day. During his ascension speech, he addressed his audience with such innocence, emotion, and cordiality that many in attendance later spoke of having been moved to tears.

No later than ten days after his accession to the throne, Ludwig increased the salaries of his servants and started working with zeal to rebuild his Bavaria. Unfortunately, this vision mostly fell on deaf ears and his initial euphoria did not last very long. Instead of politics, Ludwig poured his youthful restlessness and energy into his love of architecture and the arts.

Richard Wagner

Having been practically infatuated with Richard Wagner's works for most of his life, Ludwig finally met the artist on May 4, 1864 in the Munich Residence. According to the King's journal, both parties were enthralled by each other's passion for music and the meeting lasted over an hour and a half. Even though some high-ranking individuals of the court disapproved of Wagner’s influence over the King, Ludwig intensified the relationship, to the extent that he even became Wagner's devoted and generous benefactor.

The war of 1866

The King's pacifist convictions were unwillingly corrupted in 1866 when war broke out between Austria and Prussia, and Ludwig had no choice but to mobilize the Bavarian Army against his stronger neighbor. The turmoil and guilt that the King felt over his implicit role in a short and brutal war cause him to sink into a deep depression, and for the first time he considered abdication, a fact that he telegraphed to Richard Wagner on May 15 of that year. Prussia eventually won the so-called Seven Weeks' war, and entered into a “Schutz- und Trutzbündnis“ (defensive and protective alliance) with Bavaria, binding Ludwig's army to the victor's - a fact that would come back to haunt him only a few years later.

Engagement

In 1867, Ludwig became engaged with his cousin Sophie Charlotte, the younger sister of Empress Elisabeth of Austria. While the announcement caused much excitement in the Kingdom, the wedding day was postponed a number of times. Eventually Ludwig broke the engagement, simply saying that he did not love Sophie in the way that was required for a marital bond.

The war of 1870/71 and the foundation of the Empire

During the summer of 1870, the French-Prussian war began when Bismarck attempted to push back the French influence on Europe and extend his own dominance. Due to the aforementioned alliance, King Ludwig was forced once again send his troops to fight in a war that he did not believe in. The alliance with Prussia created huge political consequences for Ludwig, who was expected to offer his imperial crown to Wilhelm I of Prussia. After much debate, it was eventually agreed upon that despite the exchange of power, Bavaria would retain its King and, to a certain extent, its autonomy. Thus, Bavaria would be allowed to keep its current army, which would only fall under Prussian command in times of war. Although humiliating, King Ludwig signed the so-called “Kaiserbrief” (Emperor’s letter), which led to the eventual proclamation of King Wilhelm I of Prussia as emperor of the united German Reich in the Hall of Mirrors of Versailles Castle. By some accounts, Ludwig found this to be such an “affront to the French nation” that he refused to participate in the festivities.

Religion

Historians agree that King Ludwig II was a deeply religious man. Among other proclamations of his faith, his diary entry for May 7, 1864 contained the following sentence: “I want to avoid all vices with God.” He was convinced that his royalty was a divine order of God, and deplored the Prussian Empire's bloody means to gain leadership. Some historians say that his participation in the cultural war of the seventies was only half-hearted and only went so far as he saw his own claims of power endangered by those of the church.

Politics

Although politics were not the favourite activity of the Bavarian King, many historians have argued that he fulfilled his royal duties efficiently and always on time, despite accusations to the contrary. Although Ludwig spent most of his time in the mountains of Southern Bavaria, his duties remained intricately tied to the capital in Munich.

The castles

Many of Ludwig's biographers agree that his many castles were not built for pomposity's sake but rather as works of art that reflected his dreams and fantasies. It has been said that he chose to construct his own world because the “real world” could not satisfy him. Ludwig's projects varied greatly. While Herrenchiemsee was built as an homage to the Sun King, Marie Antoinette would have been delighted by the splendid decor of Linderhof Castle. Neuschwanstein Castle, his most well-known property and in itself a tribute to Richard Wagner's music and genius, would eventually become the symbol of the German heroic saga.

Ludwig was also fascinated by advances in technology to the extent that the latest achievements such as telephones and running hot water were always used in his buildings. The King designed every detail by himself, was considered an exceptional architect, and was known to spot faulty construction immediately during his inspections.

The social King

It is a little-known fact that Ludwig II was a pioneer of current models of social security. During construction of Neuschwanstein Castle he created a union to support ill workers, where in case of illness a union member would receive one Mark per day, an unheard-of benefit at that time. In the case of death, the union would take over the cost of the family's burden and arrange church services. Amazingly, this union still exists today.

The dream of flying

In 1872, Ludwig II toyed with the idea of having a flying machine built, which he hoped to one day fly over Lake Alpsee and Lake Schwansee. He even assigned this task to a number of people although it was technically impossible at the time. Sadly, this was one of the most incriminating arguments brought forth in the psychiatric report that eventually led to the King's arrest and removal from power.

Incapacitation

The removal of King Ludwig II from his throne in June of 1886 was due to a psychiatric report released by the then highly-renowned psychiatrist Dr. von Gudden. Because he declared the King to be paranoid and unable to fulfill his duties, Ludwig was arrested and the regency was taken over by Prince Luitpold, Ludwig’s uncle. Although the report was based on statements by people from the King’s immediate surroundings, historians argue that these were manipulated to make his positive and normal behaviour completely unnoticed. The fact that the King was simply eccentric never entered the debate. In fact, there was no debate, and not one of the four doctors who officially signed the report had ever examined Ludwig or even talked to him. To this day, the "objective" report remains the subject of much controversy with historians and medical professionals alike.Many theories have been brought forth to explain the actions of Ludwig's government in 1886. Interestingly, Professor Heinz Häfner from Heidelberg’s Academy of Science (Akademie der Wissenschaften) has even argued that the King was in no way "mad" or "paranoid", but that his problems resulted from a “non substance related dependency”, namely the addiction to construction! Häfner compared this to the behaviour of someone addicted to gambling.

Death

On June 13, 1886, Bavaria’s "Fairy-Tale King" was found dead in Lake Starnberg. While the actual cause of his death is still shrouded in uncertainty, the "official" explanation for the last 119 years has been suicide. Despite this, a growing number of researchers are supporting the explosive theory that Ludwig was murdered for political reasons.