Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

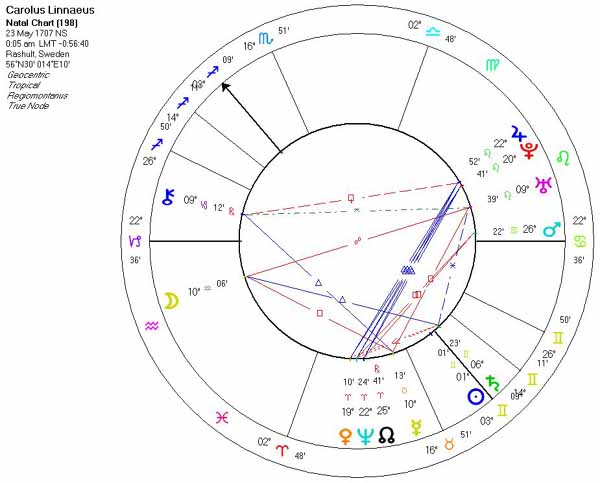

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

Nature does not make jumps

To live by medicine is to live horribly.

"If you once forfeit the confidence of your fellow citizens, you can never regain their respect and esteem. You may fool all of the people some of the time; you can even fool some of the people all the time; but you can't fool all of the people all of the time."

(Venus conjunct Neptune.)The passage was actually a quote from Linnaeus in 1797. The quote reads “Reptiles are abhorrent because of their cold body, pale color, cartilaginous skeleton, filthy skin, fierce aspect, calculating eye, offensive smell, harsh voice, squalid habitation, and terrible venom; wherefore their creator has not exerted his powers to make many of them.”

"If a tree dies plant another"

He refers to Die Luft der Freiheit weht, makes some other proposals, but expresses a preference for a Latin aphorism that was inscribed over the bedroom of the great Swedish botanist and taxonomist Linnaeus: innocue vivite, numen adest. Jordan renders this as "live blameless [sic!] in divine presence (divinity is here)." Bartlett's Familiar Quotations gives the text as "Live innocently; God is here."42 I am not sure about either translation. Another possibility would be: live righteously, God helps you.

Jordan previously had invoked the Linnaeus maxim in his address at the opening of Stanford on October 1, 1891. I quote: "For the life of the most exalted as well as the humblest of men, there can be [no] nobler motto . . . . 'This', said Linnaeus, 'is the wisdom of my life'. Every advance which we make toward the realization of the truth of the permanence and immanence of law, brings us nearer to Him who is the great First Cause of all law and phenomena."44

(Saturn conjunct Sun in Gemini.)

"Live innocently, God is here."

Biography

Carl Linnaeus was born at Råshult, in the province of Smalandia in southern Sweden. Like his father and maternal grandfather, Linnaeus was groomed as a youth to be a churchman, but he showed little enthusiasm for it. His interest in botany impressed a physician from his town and he was sent to study at Lund University, transferring to Uppsala University after one year. Linné died in Uppsala.During this time Linnaeus became convinced that in the stamens and pistils of flowers lay the basis for the classification of plants, and he wrote a short work on the subject that earned him the position of adjunct professor.

Carl Linnaeus liked to wear a dress he got by the natives in LaplandIn 1732 the Academy of Sciences at Uppsala financed his expedition to explore Lapland, then virtually unknown. The result of this was the Flora Laponica published in 1737.Thereafter Linnaeus moved to the continent. While in the Netherlands he met Jan Frederik Gronovius and showed him a draft of his work on taxonomy, the Systema Naturae. In it, the unwieldy descriptions mostly used at the time, such as "physalis amno ramosissime ramis angulosis glabris foliis dentoserratis", were replaced by the concise and now familiar genus-species names in the form Physalis angulata. Higher taxa were constructed and arranged in a simple and orderly manner. Although the system now known as binomial nomenclature was developed by the Bauhin brothers (see Gaspard Bauhin and Johann Bauhin) almost 200 years earlier, Linnaeus may be said to have popularized it within the scientific community.

Linnaeus named taxa in ways that personally struck him as common-sensical; for example, human beings are Homo sapiens (see sapience), but he also described a second human species, Homo troglodytes ("cave-dwelling man", by which he meant the chimpanzee currently most often placed in a different genus as Pan troglodytes).

The group "mammalia" are named for their mammary glands because one of the defining characteristics of mammals is that they nurse their young. Of all the features distinguishing the mammals from other animals, Linnaeus may have picked this one because of his views on the importance of natural motherhood. He campaigned against the practice of wet-nursing, declaring that even aristocratic women should be proud to nurse their own children.

Autograph of Carl v. Linné (Carolus Linnaeus)In 1739 Linnaeus married Sara Morea, daughter of a physician. He ascended to the chair of medicine at Uppsala two years later, soon exchanging it for the chair of Botany. He continued to work on his classifications, extending them to the kingdom of animals and the kingdom of minerals. The last strikes us as somewhat odd, but the theory of evolution was still a long time away, and indeed, the Lutheran Linnaeus would have been horrified by it. Linnaeus was only attempting a convenient way of categorizing the elements of the natural world.The Swedish king, Adolf Fredrik, ennobled Linnaeus in 1757, and after the privy council had confirmed the ennoblement Linnaeus took the surname von Linné, later often signing just Carl Linné. His father, born Nils Ingemarsson, had adopted the Latin surname Linnaeus as more appropriate for a clergyman on his matriculation at Lund University; the name deriving from the lime [1] tree after which the family farm, Linnagård, took its name.

Linnaean taxonomy

Although taxonomists, in almost any biological field, are familiar with the work of Carolus Linnaeus, his contribution to taxonomy goes far beyond contributing so-called scientific names to many of the world's plants and animals. Linnaeus developed, during the great 18th century expansion of natural history knowledge, what became known as the Linnaean taxonomy: the system of scientific classification now widely used in the biological sciences.The Linnaean system classified living things within a hierarchy, starting with two kingdoms. Kingdoms were divided into classes and they, in turn, into orders, families, genera (singular: genus), and species (singular: species). Since then a few other ranks have been added, most notably phyla (singular: phylum) or divisions between kingdoms and classes. Groups of organisms at any rank are now called taxa (singular: taxon) or taxonomic groups.

His groupings were based upon shared physical characteristics. Although the groupings themselves have been significantly changed since Linnaeus' conception, as well as the principles behind them, he is credited with establishing the idea of a hierarchical structure of classification based upon observable characteristics.

Linnaeus was also a pioneer in defining the (controversial) concept of "race". He proposed that inside of Homo sapiens, there were four subcategories. These categories, Americanus, Asiaticus, Africanus, and Europeanus were based on place of origin at first, and later skin color. Each race had certain characteristics that members supposedly had. Native Americans were reddish, stubborn, and angered easily. Africans were black, relaxed and negligent. Asians were sallow, avaricious, and easily distracted. Europeans were white, gentle, and inventive. Linnaeus's races were clearly skewed in favour of Europeans. Over time, this classification led to a racial hierarchy, in which Europeans were at the top.

Other accomplishments

Linnaeus is one of the finest prose writers in Swedish. His travel journals contain pithy notes on everything of interest he encountered, not just plants. He didn't just write from personal interest, but as a reporter to the enlightened scientific and political public. His journey to sub-Arctic Lapland is notable for exotic and adventurous episodes. He also composed some down-to-earth sex-instruction lectures published as "Om sättet att tillhopa gå" [How to go together].

Linnaeus' original botanical garden may still be seen in Uppsala.

He originated the practice of using the ? - (shield and arrow) Mars and ? - (hand mirror) Venus glyphs as the symbol for male and female.

Linnaeus was instrumental in the development of the Celsius (then called Centigrade) temperature scale. Anders Celsius had proposed using 0 as the boiling point of water, and 100 as the freezing point; Linneaus inverted it to the form we are familiar with today [2].

Linnaeus was one of the founders of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Linnaeus is the only human being customarily referred to by a single initial. In botany, the name (often partly abbreviated) of the person who described a species follows immediately after the scientific name: Cocos nucifera L. is the complete scientific name for the coconut, with the "L." referring to Carolus Linnaeus.

Linnaeus was said to be a man of great social skills. Karlfeldt's words "han talte med bönder på bönders vis, och med lärde män på latin" [he talked to peasants as peasants do, and to learned men in Latin] give a good characterization of his manner.Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778)

also known as Carl von Linné or Carolus Linnaeus, is often called the Father of Taxonomy. His system for naming, ranking, and classifying organisms is still in wide use today (with many changes). His ideas on classification have influenced generations of biologists during and after his own lifetime, even those opposed to the philosophical and theological roots of his work.He was born on May 23, 1707, at Stenbrohult, in the province of Småland in southern Sweden. His father, Nils Ingemarsson Linnaeus, was both an avid gardener and a Lutheran pastor, and Carl showed a deep love of plants and a fascination with their names from a very early age. Carl disappointed his parents by showing neither aptitude nor desire for the priesthood, but his family was somewhat consoled when Linnaeus entered the University of Lund in 1727 to study medicine. A year later, he transferred to the University of Uppsala, the most prestigious university in Sweden. However, its medical facilities had been neglected and had fallen into disrepair. Most of Linaeus's time at Uppsala was spent collecting and studying plants, his true love. At the time, training in botany was part of the medical curriculum, for every doctor had to prepare and prescribe drugs derived from medicinal plants. Despite being in hard financial straits, Linnaeus mounted a botanical and ethnographical expedition to Lapland in 1731 (the portrait above shows Linnaeus as a young man, wearing a version of the traditional Lapp costume and holding a shaman's drum). In 1734 he mounted another expedition to central Sweden.

Linnaeus went to the Netherlands in 1735, promptly finished his medical degree at the University of Harderwijk, and then enrolled in the University of Leiden for further studies. That same year, he published the first edition of his classification of living things, the Systema Naturae. During these years, he met or corresponded with Europe's great botanists, and continued to develop his classification scheme. Returning to Sweden in 1738, he practiced medicine (specializing in the treatment of syphilis) and lectured in Stockholm before being awarded a professorship at Uppsala in 1741. At Uppsala, he restored the University's botanical garden (arranging the plants according to his system of classification), made three more expeditions to various parts of Sweden, and inspired a generation of students. He was instrumental in arranging to have his students sent out on trade and exploration voyages to all parts of the world: nineteen of Linnaeus's students went out on these voyages of discovery. Perhaps his most famous student, Daniel Solander, was the naturalist on Captain James Cook's first round-the-world voyage, and brought back the first plant collections from Australia and the South Pacific to Europe. Anders Sparrman, another of Linnaeus's students, was a botanist on Cook's second voyage. Another student, Pehr Kalm, traveled in the northeastern American colonies for three years studying American plants. Yet another, Carl Peter Thunberg, was the first Western naturalist to visit Japan in over a century; he not only studied the flora of Japan, but taught Western medicine to Japanese practicioners. Still others of his students traveled to South America, southeast Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Many died on their travels.

Linnaeus continued to revise his Systema Naturae, which grew from a slim pamphlet to a multivolume work, as his concepts were modified and as more and more plant and animal specimens were sent to him from every corner of the globe. (The image at right shows his scientific description of the human species from the ninth edition of Systema Naturae. At the time he referred to humanity as Homo diurnis, or "man of the day". Click on the image to see an enlargement.) Linnaeus was also deeply involved with ways to make the Swedish economy more self-sufficient and less dependent on foreign trade, either by acclimatizing valuable plants to grow in Sweden, or by finding native substitutes. Unfortunately, Linnaeus's attempts to grow cacao, coffee, tea, bananas, rice, and mulberries proved unsuccessful in Sweden's cold climate. His attempts to boost the economy (and to prevent the famines that still struck Sweden at the time) by finding native Swedish plants that could be used as tea, coffee, flour, and fodder were also not generally successful. He still found time to practice medicine, eventually becoming personal physician to the Swedish royal family. In 1758 he bought the manor estate of Hammarby, outside Uppsala, where he built a small museum for his extensive personal collections. In 1761 he was granted nobility, and became Carl von Linné. His later years were marked by increasing depression and pessimism. Lingering on for several years after suffering what was probably a series of mild strokes in 1774, he died in 1778. His son, also named Carl, succeeded to his professorship at Uppsala, but never was noteworthy as a botanist. When Carl the Younger died five years later with no heirs, his mother and sisters sold the elder Linnaeus's library, manuscripts, and natural history collections to the English natural historian Sir James Edward Smith, who founded the Linnean Society of London to take care of them.

Linnaeus's Scientific Thought

Linnaeus loved nature deeply, and always retained a sense of wonder at the world of living things. His religious beliefs led him to natural theology, a school of thought dating back to Biblical times but especially flourishing around 1700: since God has created the world, it is possible to understand God's wisdom by studying His creation. As he wrote in the preface to a late edition of Systema Naturae: Creationis telluris est gloria Dei ex opere Naturae per Hominem solum -- The Earth's creation is the glory of God, as seen from the works of Nature by Man alone. The study of nature would reveal the Divine Order of God's creation, and it was the naturalist's task to construct a "natural classification" that would reveal this Order in the universe.

However, Linnaeus's plant taxonomy was based solely on the number and arrangement of the reproductive organs; a plant's class was determined by its stamens (male organs), and its order by its pistils (female organs). This resulted in many groupings that seemed unnatural. For instance, Linnaeus's Class Monoecia, Order Monadelphia included plants with separate male and female "flowers" on the same plant (Monoecia) and with multiple male organs joined onto one common base (Monadelphia). This order included conifers such as pines, firs, and cypresses (the distinction between true flowers and conifer cones was not clear), but also included a few true flowering plants, such as the castor bean. "Plants" without obvious sex organs were classified in the Class Cryptogamia, or "plants with a hidden marriage," which lumped together the algae, lichens, fungi, mosses and other bryophytes, and ferns. Linnaeus freely admitted that this produced an "artificial classification," not a natural one, which would take into account all the similarities and differences between organisms. But like many naturalists of the time, in particular Erasmus Darwin, Linnaeus attached great significance to plant sexual reproduction, which had only recently been rediscovered. Linnaeus drew some rather astonishing parallels between plant sexuality and human love: he wrote in 1729 how

The flowers' leaves. . . serve as bridal beds which the Creator has so gloriously arranged, adorned with such noble bed curtains, and perfumed with so many soft scents that the bridegroom with his bride might there celebrate their nuptials with so much the greater solemnity. . .

The sexual basis of Linnaeus's plant classification was controversial in its day; although easy to learn and use, it clearly did not give good results in many cases. Some critics also attacked it for its sexually explicit nature: one opponent, botanist Johann Siegesbeck, called it "loathsome harlotry". (Linnaeus had his revenge, however; he named a small, useless European weed Siegesbeckia.) Later systems of classification largely follow John Ray's practice of using morphological evidence from all parts of the organism in all stages of its development. What has survived of the Linnean system is its method of hierarchical classification and custom of binomial nomenclature.

For Linnaeus, species of organisms were real entities, which could be grouped into higher categories called genera (singular, genus). By itself, this was nothing new; since Aristotle, biologists had used the word genus for a group of similar organisms, and then sought to define the differentio specifica -- the specific difference of each type of organism. But opinion varied on how genera should be grouped. Naturalists of the day often used arbitrary criteria to group organisms, placing all domestic animals or all water animals together. Part of Linnaeus' innovation was the grouping of genera into higher taxa that were also based on shared similarities. In Linnaeus's original system, genera were grouped into orders, orders into classes, and classes into kingdoms. Thus the kingdom Animalia contained the class Vertebrata, which contained the order Primates, which contained the genus Homo with the species sapiens -- humanity. Later biologists added additional ranks between these to express additional levels of similarity.

Before Linnaeus, species naming practices varied. Many biologists gave the species they described long, unwieldy Latin names, which could be altered at will; a scientist comparing two descriptions of species might not be able to tell which organisms were being referred to. For instance, the common wild briar rose was referred to by different botanists as Rosa sylvestris inodora seu canina and as Rosa sylvestris alba cum rubore, folio glabro. The need for a workable naming system was made even greater by the huge number of plants and animals that were being brought back to Europe from Asia, Africa, and the Americas. After experimenting with various alternatives, Linnaeus simplified naming immensely by designating one Latin name to indicate the genus, and one as a "shorthand" name for the species. The two names make up the binomial ("two names") species name. For instance, in his two-volume work Species Plantarum (The Species of Plants), Linnaeus renamed the briar rose Rosa canina. This binomial system rapidly became the standard system for naming species. Zoological and most botanical taxonomic priority begin with Linnaeus: the oldest plant names accepted as valid today are those published in Species Plantarum, in 1753, while the oldest animal names are those in the tenth edition of Systema Naturae (1758), the first edition to use the binomial system consistently throughout. Although Linnaeus was not the first to use binomials, he was the first to use them consistently, and for this reason, Latin names that naturalists used before Linnaeus are not usually considered valid under the rules of nomenclature.

In his early years, Linnaeus believed that the species was not only real, but unchangeable -- as he wrote, Unitas in omni specie ordinem ducit (The invariability of species is the condition for order [in nature]). But Linnaeus observed how different species of plant might hybridize, to create forms which looked like new species. He abandoned the concept that species were fixed and invariable, and suggested that some -- perhaps most -- species in a genus might have arisen after the creation of the world, through hybridization. In his attempts to grow foreign plants in Sweden, Linnaeus also theorized that plant species might be altered through the process of acclimitization. Towards the end of his life, Linnaeus investigated what he thought were cases of crosses between genera, and suggested that, perhaps, new genera might also arise through hybridization.

Was Linnaeus an evolutionist? It is true that he abandoned his earlier belief in the fixity of species, and it is true that hybridization has produced new species of plants, and in some cases of animals. Yet to Linnaeus, the process of generating new species was not open-ended and unlimited. Whatever new species might have arisen from the primae speciei, the original species in the Garden of Eden, were still part of God's plan for creation, for they had always potentially been present. Linnaeus noticed the struggle for survival -- he once called Nature a "butcher's block" and a "war of all against all". However, he considered struggle and competition necessary to maintain the balance of nature, part of the Divine Order. The concept of open-ended evolution, not necessarily governed by a Divine Plan and with no predetermined goal, never occurred to Linnaeus; the idea would have shocked him. Nevertheless, Linnaeus's hierarchical classification and binomial nomenclature, much modified, have remained standard for over 200 years. His writings have been studied by every generation of naturalists, including Erasmus Darwin and Charles Darwin. The search for a "natural system" of classification is still going on -- except that what systematists try to discover and use as the basis of classification is now the evolutionary relationships of taxa.Carolus Linnaeus, also called Carl Linnaeus, was born on May 23, 1707 in Rashult, Sweden. Linnaeus began to appreciate plants and flowers at a young age. By the time he was eight years old, he was being called "the little botanist."

Linnaeus received his degree in medicine from the University of Uppsala, and he also studied at the University of Lund. Upon graduation from Uppsala, Linnaeus was appointed botany lecturer at the university.

In 1730, Linnaeus traveled to Lapland to conduct explorations. His findings were published in Amsterdam in 1737, under the title Flora Lapponica and reprinted in English under the title Lachesis Lapponica. In 1735, Linnaeus published Systema Naturae, and in 1737, Genera Plantarum. These works, which introduced a system for classifying species of plants, firmly established Linnaeus' reputation.

In 1738, Linnaeus set up a successful medical practice in Stockholm, and in 1739, he married Sara Moraea. He continued to practice medicine, teach botany, and produce works that systematized plants, animals, and minerals. His writings included Hortus Cliffortinaus (1736), Flora Suecica (1745), Fauna Suecica (1746), and many others. In 1753, he published Specieis Plantarum, which was considered one of his most important works. Linnaeus was granted a Swedish patent of nobility in 1761.

In 1774, Linnaeus had a stroke, and he died on January 10, 1778.