Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

Ambition has one heel nailed in well, though she stretch her fingers to touch the heavens.

After my mistress was dead, I lived most comfortably, my master having a great affection for me.

After that his Majesty was beheaded, the Parliament for some years effected nothing either for the publick peace or tranquillity of the nation, or settling religion as they had formerly promised.

Astrology in this time, viz. in 1633, was very rare in London, few professing it that understood any thing thereof.

I believe God rules all by his divine providence and that the stars by his permission are instruments.

I did formerly write one treatise, in the year 1639, upon the eclipse of the sun, in the eleventh degree of Gemini, May 22, 1639; it consisted of six sheets of paper.

I had not that learning from any Bookes or Manuscript... it is deduced from a caball lodging in Astrology.., the Asterismes and Signes and Constellations give greatest light thereunto.

If people suspect their Cattle Bewitched, if they be great Cattle, make the twelfth house their ascendant, and the eleventh their twelfth house, and vary your Rules with Judgment.

In November, the 18th day, I was again the second time married, and had five hundred pounds portion with that wife; she was of the nature of Mars.

In October 1633 my first wife died, and left me whatever was hers: it was considerable, very near to the value of one thousand pounds.

In that year I printed the Prophetical Merlin, and had eight pounds for the copy.

In the seventeenth year of my age my mother died.

In the year 1634, I taught Sir George Peckham, Knight, astrology, that part which concerns sickness, wherein he so profited, that in two or three months he would give a very true discovery of any disease, only by his figures.

In the years 1637 and 1638, I had great lawsuits both in the Exchequer and Chancery, about a lease I had of the annual value of eighty pounds: I got the victory.

In this year 1634, I purchased the moiety of thirteen houses in the Strand for five hundred and thirty pounds.

It happened, that after I discerned what astrology was, I went weekly into Little Britain, and bought many books of astrology, not acquainting Evans therewith.

It was my fortune, upon the sale of his books in 1634, to buy Argoll's Primum Mobile for fourteen shillings, which I only wanted.

Of my infancy I can speak little, only I do remember that in the fourth year of my age I had the measles.

Worthy sir, I take much delight to recount unto you, even all and every circumstance of my life, whether good, moderate, or evil; Deo gloria.

“Ambition has one heel nailed in well, though she stretch her fingers to touch the heaven.” An eclipse of the Sun or Moon in the watery triplicity presages a rot or consumption of the vulgar sort of people […] In Virgo or Pisces…it shows that very many fountains shall be corrupt and grow impure, and the river waters not wholesome.

Excerpted below is a selection from William Lilly's History of his Life and Times first published in 1715 and taken from a Ballantrae undated reprint of Charles Baldwin's 1822 reprint. This portion describes how Lilly became an astrologer and relates some choice anecdotes about contemporary practitioners of astrology.

How I Came to Study Astrology

It happened on one Sunday, 1632., as myself and a Justice of Peace's clerk were, before service, discoursing of many things, he chanced to say, that such a person was a great scholar, nay, so learned, that hee could make an Almanack, which to me then was strange: one speech begot another, till at last, he said, he could bring me acquainted with one Evans in Gunpowder-Alley, who had formerly lived in Staffordshire, that was an excellent wise man, and studied the Black Art. The same week after we went to Mr. Evans.

When we came to his house, he, having been drunk the night before, was upon his bed, if it be lawful to call that a bed whereon he then lay; he roused up himself, and, after some compliments, he was content to instruct me in astrology; I attended his best opportunities for seven or eight weeks, in which time I could set a figure perfectly: books he had not any, except Haly de judiciis Astrorum and Orriganus's Ephemerides ; so that as often as I entered his house, I thought I was in the wilderness.

Now something of the man: he was by birth a Welshman, a Master of Arts, and in sacred orders; he had formerly had a cure of souls in Staffordshire, but now was come to try his fortunes at London, being in a manner enforced to fly for some offences very scandalous, committed by him in these parts, where he had lately lived; for he gave judgment upon thinrs lost, the only shame of astrology: he was the most saturnine person my eyes ever beheld, either before I practised or since ; of a middle stature, broad forehead, beetle-browed, thick shoulders, flat nosed, full lips, down-looked, black curling stiff hair, splay-footed; to give him his right, he had the most piercing judgment naturally upon a figure of theft, and many other questions, that I ever met withal; yet for money he would willingly give contrary judgments, was much addicted to debauchery, and then very abusive and quarrelsome seldom without a black eye, or one mischief or other: this is the same Evans who made some many antimonial cups, upon the sale whereof he principally subsisted; he understood Latin very well, the Greek tongue not at all: he had some arts above, and beyond astrology, for he was well versed in the nature of spirits, and had many times used the circular way of invocating, as in the time of our familiarity he told me.

William Lilly is regarded as the principal authority in horary astrology. England's most illustrious astrologer, he led a colourful life in politically unstable times.

William Lilly, - known as 'the English Merlin' to his friends and 'that juggling Wizard and Imposter' to his enemies, was born in the Leicestershire village of Diseworth on 1st May 1602. [1] His ancestors were yeoman farmers, but Lilly had no inclination to follow the family tradition. By his own admission, he 'could not work, drive the plough or indure any country labour' [2] In 1613, he went to grammar school at Ashby-de-Ia-Zouch. He was taught by John Brinsley, an enlightened schoolmaster who preferred to encourage and praise his pupils rather than terrify them with the harsh discipline usually found in 17th century schools. Under Master Brinsley, Lilly gained the command of English that made his writings so popular, and also the knowledge of Latin that later enabled him to study the great authorities of classical astrology.

Lilly's ambition was to go to University and enter the Church, but his father, having fallen into debt, was unable to continue financing his education. In 1619, Lilly returned to Diseworth and taught at the village school. Then, through his father's attorney, he heard of a gentleman in London who wanted a literate youth to attend him. Lilly obtained a letter of recommendation and set out to apply for the post. He left Leicestershire on 4th April 1620. It was a cold, stormy week; Lilly walked all the way to London alongside the carrier's wagon. He arrived at half-past-three in the afternoon on Palm Sunday, 9th April 1620, and made his way to the residence of Gilbert Wright at the corner-house on the Strand. For the next 7 years Lilly was employed as Wright's servant and secretary.

When Gilbert Wright died in May 1627 he left his property to his wife, Ellen. A few months later, Lilly took the audacious step of proposing marriage to her. She accepted, despite the difference in their age and social stations. They were married on 8th September 1627 at St. George's Church, Southwark, and remained happily married until Ellen's death in 1633. She left Lilly about £1,000 which enabled him to buy a part share in 13 houses in the Strand and the lease on the corner-house. [3]

He remarried on 18th November 1634, but this marriage was disastrous. He described his second wife, Jane, as 'of the nature of Mars". The marriage lasted until her death on 16th February 1654, at which Lilly 'shedd no teares'. His third marriage, to Ruth Needham in October 1654, was the happiest of all, she being 'signified in my Nativity by Jupiter in Libra and... so totally in her condition, to my great Comfort'.

Lilly began to take a serious interest in astrology in 1632 when he was introduced to John Evans of Gunpowder Alley, 'that was an excellent wise-man and studied the Black Art'. Evans, a Welshman by birth, had formerly been a clergyman in Staffordshire but was forced to flee to London when his occult activities attracted the attention of the Church authorities. He taught Lilly the rudiments of astrology, but Lilly had a low opinion of his tutor. He disassociated himself from Evans when he caught him giving a false astrological judgement to please a paying client. Thereafter, he continued his studies on his own, building up a comprehensive library of classic texts.

Lilly began to teach and practise astrology in 1634, at a time when he was experimenting with various forms of occultism. His autobiography contains many descriptions of talismanic magic, crystal gazing, the invocation of spirits, and other 'incredibilia'. His active involvement in these practices ended when his health declined and he became 'very much afflicted with the hypochondriack melancholly, growing lean and spare and every day worse'. In May 1636 he rented a house at Hersham in Surrey, burned his magical textbooks, and lived quietly in the country for the next 5 years.

Lilly spent this period refining his astrological skills. His 'Fish Stolen' judgement, dated 10th February 1638 and given as an example chart in Christian Astrology, is a horary masterpiece. He also began to think about the wider applications of 'mundane' astrology affecting national political issues, and wrote a treatise upon the effects of the solar eclipse in Gemini, 22nd May 1639. By September 1641, Lilly had recovered his health. 'Perceiving ther was money to be gott', he returned to London and set up as a professional astrologer from his house in the Strand. He answered horary questions for a fee of half-a-crown, and soon attracted a stream of clients from all classes of society. The example horaries in Christian Astrology give an indication of the range of problems he tackled. At the peak of his popularity he was answering close to 2000 questions a year.

In February 1643, Lilly impressed Bulstrode Whitelock MP with his accurate prediction of the course of an illness. Through Whitelock, he met many members of the 'Long Parliament' engaged in directing the Civil War against King Charles I. With his interest in mundane astrology, Lilly was soon deeply embroiled in the politics of revolutionary England. His first almanac, Merlinus Anglicus Junior, published in April 1644, was an immediate best-seller and his prediction of the King's crushing defeat at the Battle of Naseby in June 1645 established his reputation as England's leading astrologer. Lilly wrote prolifically during the mid-1640s. As well as his annual almanac, he produced a series of astrological and prophetic pamphlets. His major work, Christian Astrology, was first published in 1647.

Through his writings, Lilly wielded a great deal of influence amongst the civilian population and the soldiers of the Roundhead armies. Though army 'Grandees' like Fairfax and Cromwell were inspired more by religious faith than by astrology, they certainly recognised the propaganda value of his prophecies. In 1648, he and his colleague, John Booker, were ordered to attend the siege of Colchester to encourage the troops with predictions of victory. Throughout the Civil War, both Lilly and Booker traded insults and counter-predictions with the Royalist astrologer, George Wharton, in a venomous propaganda war conducted through their almanacs and pamphlets. When the war was over, however, Wharton was imprisoned and would have been hanged if Lilly had not intervened on his behalf through his powerful friends in Parliament.

Privately, Lilly advised many leading politicians and soldiers. He was even consulted by Royalists, notably Lady Jane Whorewood, who secretly visited him 3 times in 1647-8 when she was plotting King Charles's escape from imprisonment. Not surprisingly, in view of Lilly's reputation, the King ignored his advice. Lilly has often been accused of duplicity in his dealings with the Roundheads and Cavaliers. He delighted in political intrigue, but the question of whether he was a self-seeker with an eye for the main chance, was genuinely neutral in the conflict, or was playing a subtle double-game remains a matter of opinion and conjecture.

Publicly, Lilly was identified with the Independent faction in Parliament, as against the Presbyterians who vehemently opposed astrology and all religious toleration. His comments sometimes got him into trouble. In 1645 he was hauled up before the Committee of Examinations for supporting army complaints about arrears of pay and other grievances, and in 1652 he was imprisoned for predicting that the army and the common people would combine to overthrow the new revolutionary government which had become tyrannical and oppressive. He was helped on both occasions by his influential Independent supporters, and claimed in his autobiography that Oliver Cromwell, who was about to dissolve Parliament and seize power for himself, took a personal interest in his case in 1652.

Lilly reached the height of his influence during Cromwell's Protectorate (1652-8) when the relaxation of censorship allowed him to write 'freely and satyricall inough'. Sales of his annual almanac rose to around 30,000 and some editions were translated into foreign languages. Lilly's private practice also flourished. He was consulted by Cromwell's son-in-law, John Claypole, and through him secured for his patron Bulstrode Whitelock the post of English ambassador to Sweden. Lilly ventured into international politics in 1658 by urging an English alliance with Sweden and received a gold chain and medal from the Swedish King, Charles Gustavus, in acknowledgement. Lilly's rival John Gadbury, however, supported an alliance with Denmark, then at war with Sweden, and correctly predicted the death of the Swedish monarch, which Lilly had failed to foresee. His reputation was dented again in 1659 when he predicted that Cromwell's son Richard would succeed in establishing a strong government after Oliver's death. In fact, Richard Cromwell was deposed within a few months of Lilly's prediction.

The Restoration of King Charles II in May 1660 was a worrying time for Lilly, who had become so prominent in the discredited Commonwealth. In June 1660 he was summoned to appear before a Parliamentary committee investigating the execution of Charles I, but was discharged after giving his evidence. He was arrested again in January 1661 in a general roundup of 'supposed fanatics' , but sued out a pardon and pledged his allegiance to the King, paying a fee of £13 6s. 3d. for the privilege. Lilly had made many enemies, but his reconciliation with the new regime was made easier by his friendship with the eminent Royalist, Elias Ashmole, who worked behind the scenes on his behalf. Ashmole was fascinated by magic, alchemy and astrology, and befriended many astrologers regardless of political allegiance. He first met Lilly in 1646 and was impressed when he spoke up for George Wharton in 1650. They had been firm friends ever since.

During the l660s, Lilly's practice was in decline. He continued to publish his annual almanac but censorship had been re-imposed and his sales were falling. On 27th June 1665 he left London to escape the Great Plague and settled at Hersham, having been appointed churchwarden at the parish church of Walton-upon-Thames. On 25th October 1666, he was summoned to appear before a committee investigating the causes of the Great Fire of London, which he had predicted in 1652 in the form of a coded drawing or 'hieroglyphic'. There was a suspicion that the fire had been started deliberately, and Lilly's enemies were eager to implicate him. With Ashmole's assistance though, he managed to convince the committee that his prediction was not precise and that he knew nothing about the cause of the fire. [4]

Thereafter, Lilly lived quietly and comfortably at Hersham with Ruth. He devoted much of his time to studying medicine, and in 1670 was granted a licence to practise physic. He treated the poor free of charge; the better-off paid a shilling or half-a-crown for his remedies. His friendship with Elias Ashmole deepened. In 1672 they recovered some manuscripts written by the legendary Elizabethan mystic, Doctor Dee. These, along with Lilly's own library and other astrological and mystical texts, are preserved in the Ashmolean collection at Oxford.

Lilly's last public altercation took place in 1675 when he baited and made fun of his rival Gadbury. He continued to publish his annual almanac but, because of declining health and failing eyesight, handed it over to his 'adopted son' Henry Coley with whom he collaborated closely from 1677 until his death. Lilly died of paralysis at about 3 am, 9th June 1681. He was interred a few feet from the altar at the parish church of Walton-upon-Thames. Ashmole paid for a black marble stone with a Latin inscription to his memory, which can still he seen today.

Lilly is now regarded as the principal authority in horary astrology. To many of his contemporaries though, he was seen as a prophet. From the multitude of prophecies circulating in 17th century England, Lilly adapted those attributed to the mythical Arthurian seer, Ambrosius Merlin. In The Prophecy of the White King and Dreadfull Dead Man Explained (1644) and similar publications, he applied Merlin's obscure utterances to King Charles I. The hieroglyphic drawings printed in Monarchy Or No Monarchy (1651)were derived from what Lilly called the 'secret Key of Astrology, or Propheticall Astrology'. Regarding the esoteric side to his art, he wrote:

In conventional astrology, Lilly usually gave detailed explanations of his reasoning. Thus, in England's Propheticall Merline (1644), he introduced his predictions concerning the recent conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn with a long treatise on the theory of Great Conjunctions illustrated with charts of past conjunctions and nativities of famous people. Similarly, Annus Tenebrosus or the Dark Year (1652), was published with a 'short Method to Judge the Effects of Eclipses'. Lilly was an enthusiastic astrologer and liked to share his knowledge - though some of his techniques, like his use of comets and other celestial omens, seem alien to modern practice. His Starry Messenger (1645), for example, was: 'an Interpretation of that strange Apparition of three Suns seene in London' on the King's birthday.

In 1985, a facsimile edition of Christian Astrology was published by the Regulus Press. Lilly's text, written when he was at the peak of his powers, was intended as a 'plain and easie Method for any person... to learn the Art... without any other Master than my Introduction' (i.e., Christian Astrology). Encompassing chart calculation, horary, decumbiture, nativities and directions, it was the first comprehensive astrological textbook to be written in English rather than Latin. The bibliography lists over 200 works by classical and contemporary masters. Lilly's brilliant synthesis was grounded in his own practical experience. With its down-to-earth approach and vivid glimpses into Lilly's world, Christian Astrology has become a key text in the modern revival of horary and traditional astrology.1603April 10: Death of Queen Elizabeth I. James VI of Scotland proclaimed King James I of England.1613Lilly goes to Grammar School at Ashby-de-la-Zouch where he is taught by John Brinsley, one of the finest teachers of his time.1618Death of Lilly's mother.1619Lilly leaves school. His father cannot afford to send him to university. Teaches at the village school in Diseworth1620Lilly's father in debtor's prison.April 3: Lilly leaves Leicestershire and walks to London, arriving on Palm Sunday, April 9th, at 3.30 in the afternoon. Employed as servant of Gilbert Wright, salt merchant, in the Strand.1622(1622-4) In addition to his other duties, Lilly nurses Wright's second wife who is suffering from cancer.1624September: Death of Mrs Wright1625March: Death of James I. Charles I proclaimed King.June: Gilbert Wright leaves London to avoid the plague, leaving Lilly to guard his goods.Lilly regularly attends Puritan lectures and sermons at St Antholin's church.November: Gilbert Wright returns to London; marries Ellen Whitehaire. Settles on Lilly an annual sum of £20 in recognition of his services.1627May 22: Death of Gilbert Wright. Lilly takes charge of settling his estate.September 8th: Lilly marries Ellen Wright, his late master's widow at St George's church, Southwark.October: Lilly made a freeman of the Salter's Company, London.1632Takes lessons in astrology from John Evans of Gunpowder Alley.1633October: Death of Lilly's first wife who leaves him a fortune of nearly £1,000. Lilly buys thirteen houses on the Strand and the lease on the corner house (Mr B.'s houses).1634Lilly begins studying occultism; teaches Sir George Peckham astrology; searches for buried treasure in Westminster Abbey.Lilly's first meeting with his patron William Pennington.November 18: marries Jane Rowley, "of the nature of Mars", who brings him £500 as a dowry.1635November: Death of Lilly's father.Lilly instructs Nicholas Culpeper in astrology.1636May: Lilly, suffering from "the hypochondriack mellancholly", rents a house at Hersham, Surrey, burns his magical textbooks and lives quietly in the country for the next five years.163810th February: Lilly's "Fish Stolen" horary.163922nd May: Solar eclipse in Gemini; the subject of Lilly's first astrological treatise.First Bishop's War between England and Scotland.1640Apr 13: The Short Parliament refuses to grant King Charles any money for a Scottish war unless civil and ecclesiastical grievances are settled.May 5: The Short Parliament dissolved.Jun: The Second Bishop's War. The English defeated at the Battle of Newburn.Nov 3: The Long Parliament meets. Impeachment of the King's principal ministers Strafford and Laud.1641September: Lilly, "perceiving there was money to be got", returns to London and sets up as a professional astrologer from his house in the Strand.1642August 22nd: King Charles raises the royal standard at Nottingham; the beginning of the First Civil War.November 28th: Lilly's judgement on Prince Rupert and the Earl of Essex.1643February: Lilly's first meeting with Bulstrode Whitelocke.March 18th: Lilly's horary regarding the armies of the King and Queen.April 17th: His judgement upon the outcome of the siege of Reading.November 30th: Horary pronouncing upon the last illness of John Pym.1644March 29th: Lilly's horary on the outcome of the battle of Cheriton between Sir William Waller and Sir Ralph Hopton.May 13th: Judgement upon the Earl of Essex's disasterous western campaign.June: Publication of Merlinus Anglicus Junior, Lilly's first almanac. Lilly's acrimonious first meeting with John Booker.July 2nd: The Royalists defeated at Marston Moor.August: Publication of The Prophesy of the White King.October: Publication of England's Propheticall Merline.December 3rd: Lilly's horary regarding the death of Archbishop Laud.1645Lilly clashes with George Wharton, the Cavalier astrologer.June 14th: Publication of The Starry Messenger. Lilly's prediction of a great Roundhead victory appears on the day that news reaches London of the King's defeat at the Battle of Naseby.Lilly interrogated by the Committee of Examinations for criticising the government in his almanacs. The case against him is dismissed.Publication of A Collection of Ancient and Modern Prophecies.1646May 5th: Charles I surrenders to the Scots.July 13: Surrender of Oxford; the end of the First Civil War.Lilly's first meeting with Elias Ashmole.Begins writing Christian Astrology.1647March 11th: Lilly's "Presbytery" judgement.May 27th: If Attaine the Philosopher's Stone judgement.August: Lilly consulted by Jane Whorewood regarding the King's escape from imprisonment.Lilly's portrait painted.Lilly and John Booker summoned to appear before Major-General Fairfax at Windsor who questions them on the lawfulness of astrology.November: Christian Astrology published.Publication of The World's Catastrophe, The Prophecies of Ambrose Merlin and Trithemius on the Government of the World by the Presiding Angels.1648Lilly claims to have supplied a hacksaw to facilitate Charles I's unsuccessful attempt to escape from Carisbrooke Castle.March 23: Royalist revolt against Parliament breaks out in Wales; beginning of the the Second Civil War.April 29: Lilly consulted by Richard Overton the Leveller.Summer: Attends the siege of Colchester with John Booker to encourage the Parliamentarian troops with predictions of victory.Awarded £50 and an annual pension of £100 by Parliament for his services to the Roundhead cause.Publishes A Treatise of the Three Suns.1649January 20: Lilly attends the trial of Charles IJanuary 30: King Charles beheaded.1650Procures the release of George Wharton from prison.1651Lilly publishes Monarchy or No Monarchy and Several Observations upon the Life and Death of Charles I.1652Publication of Annus Tenebrosus.Lilly buys Hurst Wood, Hersham, in the parish of Walton-upon-Thames, Surrey.October: Summoned before the Committee for Plundered Ministers for his criticisms of the government; imprisoned for 13 days but released through the influence of his political friends.1653February 16: Death of Jane, Lilly's second wife.April 20: Oliver Cromwell forcibly dissolves Parliament.1654October: marries Ruth Nedham.1655Lilly indicted for fortune-telling.1658Lilly receives a gold chain and gift of money from Charles Gustavus, King of Sweden, as a reward for publicly urging an English alliance with Sweden against Denmark.September: Death of Oliver Cromwell.1659John Gadbury criticises Lilly for failing to foresee the imminent death of the Swedish king; Lilly's reputation further dented by his prediction that Richard Cromwell would succeed in establishing a strong government after Oliver's death.1660March: The Parliament elected under the protection of General Monk call for the restoration of the monarchy. Hostile attacks by Lilly's rivals and enemies.May: Restoration of Charles II.June: Lilly examined by a Parliamentary committee enquiring into the execution of Charles I but discharged after giving evidence.October 24th: Samuel Pepys visits Lilly's house in company with Ashmole, Booker and others.1661January: Lilly arrested as a "supposed fanatic"; swears allegiance to Charles II.1664Publication of the second part of Samuel Butler's Hudibras; Lilly lampooned as the astrologer Sidrophel.1665June 27: Lilly Leaves London to avoid the Great Plague and settles in Hersham.Appointed churchwarden at Walton-upon-Thames.1666September: The Great Fire of LondonOctober 25: Lilly examined by a Parliamentary Committee investigating the causes of the Great Fire.Lilly writes his autobiography.October 8: Acquires a license to practise medicine.Lilly and Ashmole recover manuscripts written by the Elizabethan polymath Doctor Dee.Lilly's last public altercation with his rival John Gadbury.Lilly collaborates with Henry Coley on the translation into English of the Considerations of Bonatus and the Aphorisms of Cardan.June 9th, 3a.m.: Death of William Lilly.Lilly's nativity

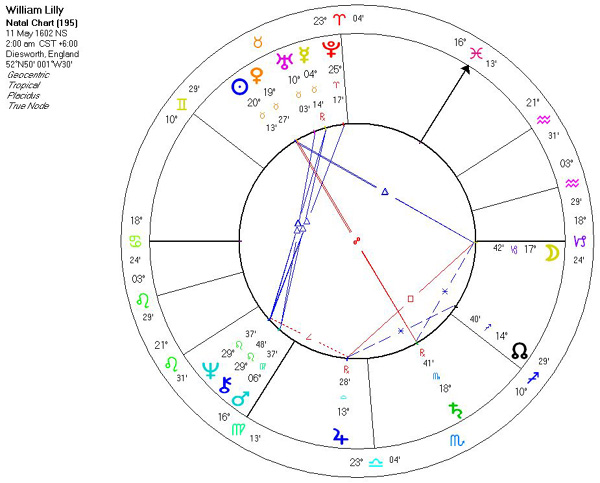

William Lilly's exact nativity isn't known ... Gadbury's version of Lilly's nativity is

a rectification performed by Mr ... The date is given as 30th April 1602 and the ...

www.skyhook.co.uk/merlin/astrol/charts/lilly.htmWilliam Lilly was the foremost English astrologer of the 17th century. Born May 1, 1602 in Diseworth, Leicestershire, he began studying astrology in 1632. In 1641 he began a professional practice and soon became heavily involved with the Parliamentary side in the English Civil War. It was said that if King Charles I could have brought over Lilly he would have been worth a half a dozen regiments. Lilly published many astrological almanacs and in 1647 wrote Christian Astrology, the most definitive work on horary astrology ever written in English. He is perhaps most famous for predicting the Great Fire of London in 1666.

After the Restoration, Lilly was repeatedly investigated as a Parliamentary supporter, but managed to escape any serious consequences. He continued his thriving astrological practice and died on June 9, 1681.