John F. Kennedy

Michael D. Robbins

© 2002

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

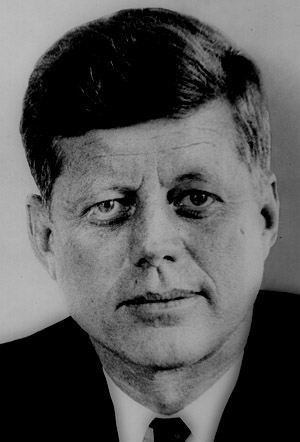

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

John Fitzgerald Kennedy

U.S. President: (1917-1963) May 29, 1917, Brookline, Massachusetts, 3:00-3:15 PM, EST. Died, November 22, 1963, Dallas Texas.

(Ascendant, Libra; MC, Cancer with Saturn conjunct MC; Sun and Venus in Gemini; Moon in Virgo; Mercury, Mars and Jupiter conjunct in Taurus; Uranus in Aquarius; Neptune in Leo conjunct Saturn in Cancer; Pluto in Cancer)

Few American presidents have captured the fascination of the world as did John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Forty-five years after his death, it is still hard to view his life and presidency objectively, and a kind of “mystique” (some would call it “glamor”) clings to his name. Perhaps glamorous Neptune in Leo (the sign of charisma and the heart) so elevated in the natal chart (conjunct the MC) contributes greatly to the optimism, uplifted vision and wistfulness which the name “President Kennedy” still awakens.

Positively, John Kennedy was known for his charisma, his brilliance and facile wit, his social idealism, courage and even heroism. On the more negative side (as the contrasts in the Gemini character are often great) he was possessed by an unrelenting ambition, opportunism, and a careless morality leading to flagrant relationships with numerous women and reputed links to notorious underworld figures. It is hard to conceive of a more colorful political figure. He was widely loved and admired (an immensely popular world-figure rather than simply an American president).Neptune threw a rosy veil over the actualities of his presidency, and offered, instead, the evocative and inspiring image of “Camelot” reborn—the Arthurian Romance transplanted to the White House. Supportive Jupiter in Taurus is also in harmonious sextile relationship with the MC (his career and reputation), enhancing his public image. As well, fortunate Jupiter is exactly conjuncted to the Vertex (point of fate), giving the needed “lift” and luck which so often came to his aid in adverse circumstances.

Kennedy’s prominent rays seem very much the first, second, fourth and sixth. The popularity of any political figure is promoted by the combination of the first and second rays. There is good reason to argue (based on his indisputable and often unsuspected courage) that his soul was focussed upon the first ray of Will and Power, and that his charming personality was to be found on the second ray. Surely his driving ambition and global breadth of thought are indications of a high first ray. In the estimation of the author, Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Delano Roosevelt had this same soul/personality combination.

The constellations transmitting the first ray are not, however, strongly represented in his chart; only Leo is tenanted by Neptune—a planet more associated with the idealism of the sixth ray and the love of the second. Aries and Capricorn have no planets. However, Mars, the orthodox ruler of Aries is found in Taurus, esoterically ruled by first ray Vulcan, and Saturn, the exoteric and esoteric ruler of Capricorn is very powerfully conjunct with the MC—within ten minutes of arc (using the 3:15 PM time).Not only does Saturn convey the first ray aspect of Capricorn (and the third and seventh ray aspects as well), but it has, of itself, a powerful first ray component. The esoteric chart ruler, Uranus, is in its own (revolutionary) sign Aquarius and square to the stellium in Taurus (Mars included).

The first ray component of both Mars and Uranus is emphasized by this square. Mercury is the orthodox ruler of Gemini and is found in Vulcan-ruled Taurus, exactly square to Uranus. First ray Pluto, the planet of death and regeneration, is also elevated and powerful—conjuncting the South Node, and in close parallel to the Vertex. There are, therefore, adequate conduits for the presumed first ray soul, and some of them are quite prominent in the chart (Saturn, Mars, Pluto and Uranus).

The second ray is well represented in the chart. Second ray Gemini holds the Sun and Venus (both ‘planets’ being astrological influences conveying the second ray), and the Moon is found in second ray Virgo conjunct the asteroid of nurturance, Ceres, with its own strong second ray component. While the Sun and Venus are only conjuncted in the broadest sense (nine degrees) together they contribute to Kennedy’s tremendous personal magnetism and appeal. Gemini is considered a sign associated with youth, youthfulness and young people; Kennedy (though in distressing physical pain, according to his brother “Bobby”, for perhaps half the days of his life {pain-inducing Chiron in the extraordinarily karmic 30th degree of Pisces) projected a remarkably youthful vitality (everywhere emphasizing physical fitness) and his appeal to the younger generation was immense.

Venus in Gemini, the orthodox ruler of the Libran Ascendant to which it is trine, contributed to JFK’s great sex-appeal (Venus trine Uranus), his promiscuity (alluring Venus in Gemini, the sign of variety) and, in general, to his popularity with women (Venus). An important ‘charismatic triangle’ is the grand trine between the Libra Ascendant, Uranus and Venus (the esoteric and exoteric rulers of Gemini respectively). This triangle conferred upon JFK a kind of electrifying appeal and make him, to many, irresistible. From a deeper and esoteric perspective, it made him a great exponent of union and unity—whether interpersonally (and sexually), socially or globally. His was an extremely attractive man with the power to bring people together, and this power of attraction lived on (and still lives) after his death.

Esoterically, the Venus/Gemini position is related to the use of the Antahkarana. Gemini is the esoteric ruler of Gemini and both are connected to the building and use of the “Bridge of Light”. Magnetic Venus draws the two poles together, and Gemini symbolizes the communication of these poles. It seems that JFK was never at a loss for inspiration (especially verbal) and that his greatest ideas, such as the Peace Corps, the Alliance for Progress, extensive civil rights legislation, and the Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty, were all part of a process of easing national and world tensions (Libra).

It seems likely that Kennedy’s brilliant mind was upon the colorful fourth ray, accounting for both his sparkling eloquence and ready wit. Mercury is placed in fourth ray Taurus, which could seem to slow the mind, but such was not the case, as Mercury was conjunct to both activating Mars and comprehensive Jupiter—all these square to inspirational, electric Uranus (in its own electrifying sign—Aquarius). The power, scope and assertiveness of Kennedy’s thought are to be seen in this triple conjunction—its square to galvanic Uranus and its harmonizing trine to the critical and astute Virgo Moon.His power to debate (Mars conjunct Mercury) and to win, (successful Jupiter conjunct both Mars and Mercury), are shown in this Taurus stellium, indicating the incisiveness, power and breadth of his mind. Like Alice Bailey (another individual with a Gemini Sun sign) he was said to be able to read at a phenomenally rapid rate, a page at a time, at speeds reported to be upwards of fifteen hundred words per minute). In such skills, one recognizes the Geminian abilities and also the results of the stellium here discussed. His success as an author (Sun and Venus in Gemini, Jupiter conjunct Mercury) is notable: Profiles in Courage (Mars conjunct Mercury) for which he was awarded the 1957 Pulitzer Prize and Why England Slept.

Kennedy’s idealism cannot be denied (though balanced by a fair measure of political realism and opportunism—Saturn conjunct the MC, and Libra Rising). The two planets conveying the sixth ray (Mars and Neptune) are in quintile relationship (blending intelligence and originality with the idealism), and communicative Mercury is part of this quintile. The result is the passionate and intelligent expression of idealism. If there is any ray to rival the first ray for the rulership of the soul, it would be the idealistic sixth ray. Surely, he was, at heart, a political idealist.

The Libran Ascendant represents the energy which, properly used, lead towards the expression of the soul. Libra contributed to JFK’s great popularity—globally, socially, and privately. It gave him charm, grace, and a beautiful image; he was in the eyes of many, a handsome man (a quality which the Venus-ruled Libra Ascendant) can often confer. On a deeper level, when one thinks of the Peace Corps (so revolutionary an idea at the time—Uranus {revolution} trine both Venus and the Libra Ascendant) one must realize the profoundly Libran nature of this initiative. With its inception arose the concept of “waging peace”. Here we can see the combined influence of Libra and the sixth ray (supported by the second and first).

It is difficult (and, perhaps, even inadvisable) to speculate about such matters, but it may be that Kennedy’s monadic ray (like Lincoln’s {speculatively}) was the second. It seemed to be his underlying “mission” to unite the American people in support of its highest ideals, to remove the tarnish from the practice of government, and re-emphasize the soul-principles upon which the American nation was founded.Of course his own personal, private life was often lived in contradistinction to these ideas (as dualistic Gemini might suggest), but it cannot be denied that he elevated the vision of both America and the world. In his own character, the contrast between the ideal and the actual was stark, but those who loved him appreciated the opportunity to think about their leader and their own possibilities in more beautiful and cultured terms, and this, JFK and his wife, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, made possible.

It is amazing that only after his death did word of his sexual escapades begin to reach the public. And even with this revelation, his image, somehow, is protected. Of course Libra is associated with “unbalanced fiery passion, human love”, and JFK’s eighth house (sex and death, among other things) is very full—especially with Taurean planets (Taurus being one of the primary sexual signs and closely related to the desires of the instinctual nature). (William Clinton has a Libran Ascendant and a Taurus Moon.) Also, Pluto (raising to light the ‘sins’ of the lower worlds) is closely conjunct JFK’s South Node (hence his reputed “underworld” connections, and his many liaisons which had to be hidden by the Secret Service). The quite close trine between affiliative Venus in the sign of diversity, Gemini, and Juno, the asteroid of marriage and relationship in Aquarius (indicating ‘marriage’ to many or to the group), certainly heightened his promiscuity. A personality upon the second ray (the glamor of which is, so often, “the love of being loved” would only add to the tendency).

One asteroid (Vesta) and one planetoid, (Chiron) also tell a most interesting story. They are placed late in the sixth ray/second ray sign, Pisces, adding to the idealism and highly stimulated love-nature already emphasized. Chiron is the planet of pain and healing, and is placed in the highly karmic last degree of Pisces, and also closely conjunct to the still-Piscean cusp (by Placidus) of the sixth house of sickness and health.Was JFK (as a soul, though probably unconsciously) taking upon himself a burden of collective karma, for the last degree of Pisces is the most collectively synthetic degree of the zodiac? The close proximity of Vesta (the asteroid of commitment, and also in Pisces) to Chiron, tells of his devotion to the cause of healing (as healing can be administered via the political process). His many proposed social welfare programs, and proposed civil rights legislation stem from this motivation.

Although the scion of a wealthy family, and born to hereditary financial privilege (Jupiter in Taurus in the eighth house of inheritance and legacies), he, nevertheless, was a would-be champion (Vesta/Chiron) of those less fortunate than himself (Pisces planets in relation to the sixth house of “servants”). In this, he shared certain characteristics with Franklin Delano Roosevelt, also a member of the East-Coast upper class and also animated by the desire to raise the lot of those of lesser social standing.

A great deal of family karma is indicated by the elevated and karmic Saturn in its “detriment” position in Cancer, conjunct the MC. Capricorn, of which Saturn is twice the ruler, is the sign archetypally associated with the “father” and Cancer with the “mother”.The great ambitions of patriarch Joseph Kennedy for this family were absorbed and enacted by JFK; after the death of his brother, Joe, his father’s expectations fell upon him, and he lived out that expectation through a drive for political prominence. His mother, Rose Kennedy, was said to be “distant” (Saturn, the planet of separation in the Cancer, the sign of material intimacy). His father was virtually absent from his childhood. These two conditions (both characteristic of his prominent Saturn) set the stage for JFK’s determination to rise politically and, in general, for his will to prove himself, not only in the pursuit of political power but in pursuit and conquest of women.

Yet another karmic indicator is the as-yet-undiscovered planet Sigma (which some call the “esoteric Saturn”). In JFK’s chart it is located in nine (plus) degrees of Gemini quite close to his Gemini Sun. The Elevated Saturn and Sigma so prominent, along with Chiron in the last degree of Pisces, shows his life as one of ‘karmic reaping’, and sacrificial to an important extent. To what degree this sacrificial quality was conscious may be debated.

Esoterically, Saturn is the planet of opportunity, especially disciplic opportunity—achieved often through pain.“The power of Saturn in this sign furthers the ends and purposes of the governing energies or rays of harmony through conflicts (the Moon and Mercury) and of Neptune, for in this sign Saturn is in the home of its detriment and thus produces those difficult conditions and situations which will lead to the needed struggle. This makes Cancer a place of symbolic imprisonment and emphasises the pains and penalties of wrong orientation. It is the conflict of the soul with its environment—consciously or unconsciously carried on—which leads to the penalties of incarnation and which provides those conditions of suffering which the soul has willingly undertaken when—with open eyes and clear vision—the soul chose the path of earth life with all its consequent sacrifices and pains, in order to salvage the lives with which it had an affinity.” (EA 342)

Physical pain (through his back problems, caused by an injury during this teens—Uranus square Mars/Mercury, and Addison’s Disease with its suppression of his adrenal function) was his constant companion—his symbolic “cross to bear”. Additionally, he carried the psychological burden (Saturn) of his family dynamics and upbringing (Cancer) throughout his life, and this influenced much of his approach to his public career (MC). Viewed from this angle, his great drive towards political success was, partially, at least, the result of compensation, though naturally, its deeper roots were to be found in the will of his soul.

Certainly, in JFK’s life, the “pains and penalties of wrong orientation” were prominent. The pains (both physical and psychological), though well hidden by his brilliantly charming manner, were constant. As well, many will look at his dramatic death as evidence of the penalties exacted because of wrong orientation. Two conspiracy theories concerning his death place the blame upon the Mafia (with some members of which he reputedly had inappropriate relations) or upon the Cuban Government (angered by the ill-advised and abortive Bay of Pigs Invasion).John F. Kennedy, was clearly a disciple (albeit with some major personal flaws); in the life of a disciple, penalties for such flaws are exacted rather rapidly, especially on that part of the path of discipleship which is also the path of initiation.

Some of the declinations are also of interest. There is quite a close parallel between Saturn and the Sun on one side and Saturn and the MC on the other, emphasizing again, responsibility, karma, ambition, and the pressure exerted by the father and family tradition (Saturn as pressure, and Cancer as family tradition). An elevated Saturn often indicates a rise to (and fall from) political power. Hitler also had such a prominent Saturn (though his character and motivations were entirely different from JFK’s). Parallels and contra-parallels of declination act similarly to conjunctions and oppositions respectively, and must be considered along with longitudinal aspects.

As well we see a very close parallel between Pluto (planet of death, sex, regeneration, the negative forces and the raising of all that is hidden) and the Vertex (the point of fate). This reinforces the longitudinal conjunction of Pluto with the South Node, and tells of JFK’s fated confrontation with the forces of negativity—whether in society or within his own nature. Perhaps, as well, it tells of his ‘appointment’ with assassination.

One other connection by declination is of note—the close contra-parallel between Uranus and Mercury, which are already very closely in square by longitudinal aspect. The originality and surprising brilliance of the mind are thereby emphasized, and his impact as a communicator with the power to awaken thought.

His ambitious, expansive Mars/Jupiter longitudinal conjunction is reinforces by a parallel between the two, to which Ceres adds its power to nurture and cultivate. Taurus is a sign of great desire, and the presence of Mars and Jupiter conjuncted in Taurus (and reinforced by parallel) strengthens and expands these desires.We can see if we look closely at JFK (both his character and physiognomy) the influence of Taurus, which contains Mercury, the orthodoxly ruling planet of his Gemini Sun). Gemini individuals are much influenced by the position of Mercury (a planet which easily takes on the coloring of the sign in which it is found). This Taurus position for Mercury would add a degree of assurance and even stubbornness to JFK’s mind, which he certainly demonstrated during the thirteen day stand-off with the Soviet Union over the presence of nuclear missiles in Cuba.

In the chart of so prominent an individual, the fixed stars could be expected to play a significant role, and, indeed, they do. The Sun in Gemini is conjuncted to Aldebaran, which might be called the ‘Star of Integrity’. Clearly JFK’s character was divided—idealistic, progressive and liberal in one way, yet arrogant, ambitious, careless and promiscuous in another. The public did not learn of his disintegrous behavior until after his death (and even then, it did not make much impact). But when one of the “Four Royal Stars” is conjunct the Sun, there is a life-lesson being offered; had he lived, the issue of integrity would have faced him squarely (just as it has faced William Clinton), and his downfall may have been a strong possibility (as Saturn conjunct the MC often indicates).

Venus (already implicated in his great sex-appeal) was closely parallel the star Hamal, associated with aggression, crudeness, brutishness, and, in some, even sadism. Certainly, it is a coarsening influence. It would strengthen the passions and make one determined to indulge the lower aspects of Venus. It would contribute to the headstrong recklessness within which JFK pursued women. Regardless of his political and social responsibilities he, in his love-life, acted in an independent and even arrogant manner. Venus, it should be noted, is also in the eighth house representing tests and vices to be overcome.

Along this same line, expansive Jupiter is exactly conjunct Capulus, the “sword of Perseus”, the star associated, according to Bernadette Brady, with libido and “male sexual energy”. This certainly added to what might be called the ‘zestful pursuit’ of his amorous adventures. The Vertex, as well, is conjunct Capulus, and, we remember, also parallel the planet Pluto. These both reinforce the role which compulsive sexual expression played in his life. This prominence of Capulus also added to JFK’s capability to display “macho” behavior—perhaps not to be expected in one with so much Libra and Gemini.

As well there is a close parallel of Saturn to Zosma, in the “back of the Lion”. Zosma is not a particularly felicitous star, indicating either the victim or the savior. Some accounts associate it with “selfishness, immorality and drug additions” (Larousse Encyclopedia of Astrology). It is well known that JFK (and Jacqueline) took frequent amphetamine injections to cope with the strain of their position. The factor of immorality is well known. Zosma may also be associated with the persecution of the feminine. Its conjunction with elevated Saturn again indicates the karmic themes of JFK’s life—his role as the “victim” of his heredity and family culture. In a way, he was sacrificed upon the altar of family expectation.

A very strong combination involving Spica, Arcturus and Zuben Elschamali connect with the Ascendant—Spica and Arcturus by longitudinal conjunction and Zuben Elschamali by parallel. Arcturus and Spica are two most felicitous stars. Spica confers brilliance. Brady tells us that “Spica represents the goddess’ gift of new knowledge and gives a potential for brilliance in any chart it touches”. It is considered extremely fortunate conferring happiness, preferment, honor and advancement.Arcturus is said to give the daring to strike out and take a new path, to try new methods, to take a road which has not been trodden. We can see both these stars at work in JFK’s life and presidency. His mind was fertile with new initiatives for social welfare and betterment, and he surprised many by his boldness and originality. Zuben Elschamali is considered a star of “social reform”, but often with negative consequences. Indeed, JFK was largely unsupported (by Congress and the Senate) in his desires for social reform, and his proposals had to wait for his death to be enacted under another administration.

The most dramatic life episode (of a number of dramatic episodes) was the manner of John Kennedy’s death—a sudden death by assassination. We are reminded of the deaths of Gandhi and of Martin Luther King—both prominent social reformers and both ‘removed’ suddenly by assassination. One wonders about the ‘staging’ arranged by the soul, perhaps for the sake of emphasizing the message of these great leaders. So it was for John Kennedy.

When we seek the manner of death we look to the eighth house, and we see violent Mars conjunct the eighth house cusp. Kennedy was shot, and Mars represents fire-arms. Mercury is there, as well, conjunct Mars, so a plan was involved, and interestingly, it occurred while JFK was traveling in a motorcade (Mercury). Mars and Mercury rule motorized vehicles.The suddenness of the death is indicated by Uranus (the planet of the sudden and unexpected) in square to both Mars and Mercury, and in square to the Vertex (point of fate) to which Pluto is parallel and Capulus conjuncted.

The validity of the astrology of fate is dramatically revealed by the solar eclipse of July 21, 1963 which occurs on the very degree of Kennedy’s karmic, elevated and highly prominent Saturn. Eclipses, which engineer the precipitation of events, are in effect for approximately six months after their occurrence, and so the date of assassination, November 22, 1963, was well within range.Some say eciplises become effective before the occurrence and some that their effect can last even a year. Kennedy’s dramatic assassination signaled the sudden end of his career. Indeed it was a karmic event of the highest order and in every respect the kind of “fall from power” long associated with an elevated Saturn. Saturn is the ruler of house four (of home and country) and conjuncts house ten of governments. Kennedy’s death was an international event, affecting multitudes and reaching personally into almost every home in the world and seriously affecting global stability (MC/IC axis).

When one is faced with the life of so prominent a disciple one seeks to understand the meaning of the life in terms of the soul. We might say that John Fitzgerald Kennedy presented America and the world with a new and higher idealism, and new vision. He enunciated a kind of selflessness which he exemplified in his higher moments (as when he was responsible for saving the lives of the men under his command when his PT-109 torpedo boat was destroyed), but to which standard many other aspects of his life did not conform. Yet his overall effect was profound and influential far beyond the measure of his personal behavior. He presented the America and the world with a vision of renewal (astrologically correlated with his elevated, inspired and inspiring Neptune, his prominent regenerative Pluto {in the ninth house of higher mind, vision and internationalism} and visionary Jupiter conjunct Vertex, Mercury and Mars).It can be said that he brought hope that a higher way of national and international life was, indeed, possible. Perhaps he was, as it were, ‘removed’, before this optimistic and uplifting vision of possibility could be too severely tarnished by word of those aspects of his character which did not live up to that vision.

Although in many ways he was a selfish and self-indulgent man, the legacy of JFK is somehow associated with selflessness, with thinking beyond the needs and concerns of the petty little self, of asking not “what your country can do for you” but “what you can do for your country”. Thus the idealism is clear, and the sixth ray important.

Had JFK’s ideals been fulfilled, there would have been a more civilized, cultured discourse between the members of society and between nations in general, and beautification of the environment would have advanced. He brought a new level of intelligence (Gemini) to the Presidency of the United States, and, apparently, a beacon of hope that the tawdriness of conventional politics could be transcended. Of course, he could be accused of hypocrisy (as is the fate of so many divided Gemini individuals).The life of his large soul and the tendencies of his often immature personality were two quite different things. The soul and its instrument Fate, however, arranged that despite his continuing indiscretions, he would have no choice (Saturn and Pluto) but to live out a purpose larger than his own, bringing a vision to the world of intelligent (Gemini) social justice (Libra) and right human relations in a more peaceful world.

Perhaps JFK’s visionary qualities are nowhere more potently symbolized than in his commitment in May 1961 to land a man on the Moon by the end of the decade. His prophetic commitment would prove correct but he would never live to see its fulfillment. So many of his visions (Neptune in the tenth house conjunct the MC) would only later materialize. We might think of his life as a king of annunciation of greater possibilities towards which not just America but humanity might strive.

We might think of his life in relation to his highly successful book, Profiles in Courage. Though he was weak as a child, and throughout his life had many physical and psychological liabilities to overcome (products of his proposed second ray personality), he knew how to rise to the occasion—whether in actual combat or when the world stood for thirteen days on the brink of nuclear war. Nikita Khrushchev, mislead by JFK’s charming and apparently pleasure-loving second ray personality, and the inoffensive signs Gemini and Libra, thought that he had taken the measure of the man, and so could attempt bold and aggressive moves internationally to compromise the United States in the “balance of terror” then prevailing. He had not, however, taken the measure of John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s first ray soul, which showed itself (when needed) in great fortitude and courage.

The tragedy (so it seems) is that JFK was cut down in his prime, before he could demonstrate his true promise and greatness. It could be argued, however, that decisive karma was at play (the solar eclipse on Saturn) and that the soul extracted the full measure of quality from his life in such as way as to enhance the inspiration of the vision he presented humanity.

Quotes

With a good conscience our only sure reward, with history the final judge of our deeds, let us go forth to lead the land we love, asking His blessing and His help, but knowing that here on earth God’s work must truly be our own.

My fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country. My fellow citizens of the world, ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.

Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.

This country cannot afford to be materially rich and spiritually poor.This country cannot afford to be materially rich and spiritually poor.

(Saturn conjunct Neptune on Midheaven.)I look forward to an America which will reward achievement in the arts as we reward achievement in business or statecraft. I look forward to an America which will steadily raise the standards of artistic accomplishment and which will steadily enlarge cultural opportunities for all of our citizens. And I look forward to an America which commands respect throughout the world not only for its strength but for its civilization as well.

(Venus in Gemini conjunct Sun & trine Uranus.)Now the trumpet summons us again—not as a call to bear arms, though arms we need—not as a call to battle, though embattled we are—but a call to bear the burden of a long twilight struggle, year in and year out, “rejoicing in hope, patient in tribulation”—a struggle against the common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease and war itself.

Uranus in Aquarius square Mars.)In the long history of the world, only a few generations have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger. I do not shrink from this responsibility—I welcome it.In the long history of the world, only a few generations have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger. I do not shrink from this responsibility—I welcome it.

(Mars square Uranus.)If we cannot end now our differences, at least we can help make the world safe for diversity.

(Libra Ascendant.)Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.

(Venus in 8th house square Moon in Virgo.)Let us never negotiate out of fear. But let us never fear to negotiate.

(Libra Ascendant.)To those peoples in the huts and villages of half the globe struggling to break the bonds of mass misery, we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves, for whatever period is required—not because the communists may be doing it, not because we seek their votes, but because it is right. If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich.

(Uranus in Aquarius.)When power leads man towards arrogance, poetry reminds him of his limitations. When power narrows the area of man’s concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses.

(Mercury conjunct Mars.)Forgive your enemies, but never forget their names.

When written in Chinese the word crisis is composed of two characters. One represents danger and the other represents opportunity.

(Saturn on Midheaven.)The new frontier of which I speak is not a set of promises—it is a set of challenges. It sums up not what I intend to offer the American people, but what I intend to ask of them. It appeals to their pride, not their pocketbook—it holds out the promise of more sacrifice instead of more security.

(Neptune & Saturn conjunct MC.)When power leads man toward arrogance, poetry reminds him of his limitations. When power narrows the area of man’s concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses.

(Mars conjunct Mercury square Uranus.)Our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children's future. And we are all mortal.

The greater our knowledge increases the more our ignorance unfolds.

Do not pray for easy lives. Pray to be stronger men.

Mankind must put an end to war before war puts an end to mankind.

The time to repair the roof is when the sun is shining.

Things do not happen. Things are made to happen.

We are not afraid to entrust the American people with unpleasant facts, foreign ideas, alien philosophies, and competitive values. For a nation that is afraid to let its people judge the truth and falsehood in an open market is a nation that is afraid of its people.

For time and the world do not stand still. Change is the law of life. And those who look only to the past or the present are certain to miss the future.

(Stellium in 8th house.)Tolerance implies no lack of commitment to one's own beliefs. Rather it condemns the oppression or persecution of others.

I'm an idealist without illusions.

(Neptune conjunct Saturn.)Politics is like football; if you see daylight, go through the hole.

The basic problems facing the world today are not susceptible to a military solution.

I am sorry to say that there is too much point to the wisecrack that life is extinct on other planets because their scientists were more advanced than ours.

History is a relentless master. It has no present, only the past rushing into the future. To try to hold fast is to be swept aside.

Let us not seek the Republican answer or the Democratic answer, but the right answer. Let us not seek to fix the blame for the past. Let us accept our own responsibility for the future.

A man may die, nations may rise and fall, but an idea lives on.

A revolution is coming - a revolution which will be peaceful if we are wise enough; compassionate if we care enough; successful if we are fortunate enough - but a revolution which is coming whether we will it or not. We can affect its character, we cannot alter its inevitability.

The problems of the world cannot possibly be solved by skeptics or cynics whose horizons are limited by the obvious realities. We need men who can dream of things that never were.

The very word 'secrecy' is repugnant in a free and open society; and we are as a people inherently and historically opposed to secret societies, to secret oaths, and to secret proceedings.

Our problems are man-made, therefore they may be solved by man. And man can be a s big as he wants. No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings.

Peace is a daily, a weekly, a monthly process, gradually changing opinions, slowly eroding old barriers, quietly building new structures.

Date of birth: May 29, 1917

Place of birth: Brookline, Massachusetts

Date of death: November 22, 1963

Place of death: Dallas, Texas

First Lady: Jacqueline Lee Bouvier Kennedy

Political party: Democratic

JFK redirects here. For other uses, see JFK (disambiguation).

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to as Jack Kennedy or JFK, was the 35th President of the United States (1961–1963). His assassination on November 22, 1963 was a defining moment of 1960s American history, as his death was mourned around the world, and many international leaders walked behind the casket at his funeral.The youngest person ever to be elected president of the U.S. (Theodore Roosevelt being the youngest ever to serve as president), Kennedy was also the youngest President ever to die—at 46 years and 177 days. He is also the only Roman Catholic ever to be elected president, the last Democratic Party candidate from a Northern state to be elected president, the first President to serve who was born in the 20th century, and the last president to die in office.

Major events during his presidency included the Cuban Missile Crisis, the building of the Berlin Wall, the Space Race, early events of the Vietnam War, and the Civil Rights Movement. He is rated highly in many surveys that rank presidents, but his political agenda was still incomplete at his death with most of his civil rights policies coming to fruition through his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson.

Early life and education

Kennedy was born in Brookline, Massachusetts, the son of Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr. and Rose Fitzgerald. As a young man he attended The Choate School, an elite private school. Before enrolling in college, he attended the London School of Economics for a year, studying political economy. In the fall of 1935, he enrolled in Princeton University, but was forced to leave during Christmas break after contracting jaundice. The next fall, he began attending Harvard University. Kennedy traveled to Europe twice during his years at Harvard, visiting the United Kingdom, while his father was serving as Ambassador to the Court of St. James's. In 1937, Kennedy was erroneously prescribed steroids to control his colitis, which only heightened his medical problems causing him to develop osteoporosis of the lower lumbar spine [1].In 1938, Kennedy wrote his honors thesis on the British portion of the Munich Agreement. He was an average student at Harvard, never earning an A, but mostly B's and C's, with a single D in a sophomore history course. He graduated cum laude from Harvard with a degree in international affairs in June 1940. His thesis, entitled Why England Slept, was published in 1940 and, with the aid of his affluent and powerful father, it became a best-seller.

Military service

In the spring of 1941, Kennedy volunteered for the U.S. Army, but was rejected, mainly because of his troublesome back. However, the U.S. Navy accepted him in September of that year. He participated in various commands in the Pacific Theater and earned the rank of lieutenant, commanding a patrol torpedo boat or PT boat.Jack on his navy patrol boat, PT 109.On August 2, 1943, Kennedy's boat, the PT-109, was taking part in a night-time military raid near New Georgia (near the Solomon Islands) when it was rammed by a Japanese destroyer. Kennedy was thrown across the deck, injuring his already troubled back. Still, Kennedy somehow towed a wounded man three miles through the ocean, arriving on an island where his crew was subsequently rescued. Kennedy said that he blacked out for periods of time during the ordeal. For these actions, Kennedy received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal under the following citation:

"For heroism the rescue of 3 men following the ramming and sinking of his motor torpedo boat while attempting a torpedo attack on a Japanese destroyer in the Solomon Islands area on the night of Aug 1-2, 1943. Lt. KENNEDY, Capt. of the boat, directed the rescue of the crew and personally rescued 3 men, one of whom was seriously injured. During the following 6 days, he succeeded in getting his crew ashore, and after swimming many hours attempting to secure aid and food, finally effected the rescue of the men. His courage, endurance and excellent leadership contributed to the saving of several lives and was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service."

Kennedy's other decorations of the Second World War include the Purple Heart, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal. He was honorably discharged in early 1945, just a few months before the Japanese surrendered.In May 2002 a National Geographic expedition found what is believed to be the wreckage of the PT-109 in the Solomon Islands [2].

Early political career

After World War II, Kennedy entered politics (partly to fill the void of his popular brother, Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr., on whom his family had pinned many of their hopes but who was killed in the war). In 1946, Representative James Michael Curley vacated his seat in an overwhelmingly Democratic district to become mayor of Boston and Kennedy ran for that seat, beating his Republican opponent by a large margin. He was reelected two times, but had a mixed voting record, often diverging from President Harry S. Truman and the rest of the Democratic Party.A young Senator Kennedy in 1953.In 1952, Kennedy ran for the Senate with the slogan "Kennedy will do more for Massachusetts." In an upset victory, he defeated Republican incumbent Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. by a margin of about 70,000 votes. Kennedy adroitly dodged criticizing fellow Senator Joseph McCarthy's controversial campaign to root out Communists and Soviet spies in the U.S. government, because of McCarthy's popularity in Massachusetts. McCarthy was a friend of Kennedy, Kennedy's father, dated the Kennedy sisters, and younger brother Robert F. Kennedy briefly worked for McCarthy. Although Kennedy was ill during the 65–22 vote to censure McCarthy, he was criticized by McCarthy opponents such as Eleanor Roosevelt who later said of the episode, "he should have displayed less profile, and more courage".

Kennedy married Jacqueline Bouvier on September 12, 1953. He underwent several spinal operations in the two following years, nearly dying (receiving the Catholic faith's "last rites" four times during his life), and was often absent from the Senate. During this period, he published Profiles in Courage, highlighting eight instances in which U.S. Senators risked their careers by standing by their personal beliefs. The book was awarded the 1957 Pulitzer Prize for Biography.

In 1956, Kennedy campaigned for the Vice Presidential nomination at the Democratic National Convention, but convention delegates selected Tennessee senator Estes Kefauver instead. However, Kennedy's efforts helped bolster the young Senator's reputation within the party.

An example of Kennedy's political suppleness, prior to the 1960 campaign, was his handling of the Civil Rights Act of 1957. He voted for final passage, while earlier voting for the "jury trial amendment", which rendered the Act toothless. He was able to say to both sides that he supported them.

1960 Presidential election

Kennedy shakes Richard Nixon's hand before a televised debate.In 1960, Kennedy declared his intent to run for President of the United States. In the Democratic primary election, he faced challenges from Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota, Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas, and Adlai Stevenson, the Democratic nominee in 1952 and 1956 who was not officially running but was a favorite write-in candidate. Kennedy won key primaries like Wisconsin and West Virginia and landed the nomination at the Democratic National Convention in 1960.On July 13, 1960 the Democratic Party nominated Kennedy as its candidate for president. Kennedy asked Johnson to be his Vice Presidential candidate, despite clashes between the two during the primary elections. He needed Johnson's strength in the South to win the closest election since 1916. Major issues included how to get the economy moving again, Kennedy's Catholicism, Cuba, and whether or not both the Soviet space and missile programs had surpassed those of the U.S.

In September and October, Kennedy debated Republican candidate Vice President Richard Nixon in the first ever televised presidential debates. During the debates, Nixon looked tense, sweaty, and unshaven contrasted to Kennedy's composure and handsomeness, leading many to deem Kennedy the winner, although historians consider the two evenly matched as orators. Interestingly, many who listened on radio thought Nixon more impressive in the debate.[3] The debates are considered a political landmark: the point at which the medium of television played an important role in politics and looking presentable on camera became one of the important considerations for presidential and other political candidates.

In the general election on November 8, 1960, Kennedy beat Nixon in a very close race. There were serious allegations that vote fraud in Texas and Illinois had cost Nixon the presidency[4]. Especially troubling were the unusually huge margins in Richard Daley's Chicago — which were announced after the rest of the vote in Illinois. The only change after the official recount was a win for Kennedy in Hawaii.

Presidency

Kennedy gives his memorable inauguration addressKennedy was sworn in as the 35th President on January 20, 1961. In his inaugural address he spoke of the need for all Americans to be active citizens. "Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country", he said. He also asked the nations of the world to join together to fight what he called the "common enemies of man... tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself".Foreign policies

On April 17, 1961, Kennedy gave orders allowing an previously-planned invasion of Cuba to proceed. The operation's official name is in dispute, however some sources claim it was called Operation Zapata. With support from the CIA, in what is known as the Bay of Pigs Invasion, 1,500 U.S.-trained Cuban exiles, called "Brigade 2506" returned to the island in the hope of deposing Castro, but the CIA had overestimated popular resistance to Castro, made several mistakes in devising and carrying out the plan, and the exiles did not rally the Cuban people as expected. By April 19 Castro's government had killed or captured most of the exiles and Kennedy was forced to negotiate for the release for the 1,189 survivors. After 20 months, Cuba released the exiles in exchange for $53 million worth of food and medicine. The incident was a major embarrassment for Kennedy, but he took full responsibility for the debacle (See Bay of Pigs Invasion for more information).On August 13, 1961, the East German government began construction of the Berlin Wall separating East Berlin from the Western sector of the city, due to the American military presence in West Berlin. Some claimed this action was in violation of the "Four Powers" agreements. Kennedy initiated no action to have it dismantled, and did little to reverse or halt the eventual extension of this barrier to a length of 155 km.

The Cuban Missile Crisis began on October 14, 1962 when American U-2 spy planes took photographs of a Soviet intermediate range ballistic missile site under construction in Cuba. Kennedy faced a dire dilemma: if the U.S. attacked the sites it might have led to nuclear war with the U.S.S.R. If the U.S. did nothing, it would endure the perpetual threat of tactical nuclear weapons within its region, in such close proximity, that if launched pre-emptively, the U.S. may have been unable to retaliate. Another fear was that the U.S. would appear to the world as weak in its own hemisphere. Many military officials and cabinet members pressed for an air assault on the missile sites but Kennedy ordered a naval blockade and began negotiations with the Russians. A week later, he and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev reached an agreement. Khrushchev agreed to remove the missiles if the U.S. would publicly agree never to invade Cuba, and also secretly agree to remove U.S. ballistic missiles from Turkey within six months. Following this incident, which brought the world closer to nuclear war than at any point before or since, Kennedy was more cautious in confronting the Soviet Union. The promise to never invade Cuba still stood as of 2005.

Arguing that "those who make peaceful revolution impossible, make violent revolution inevitable", Kennedy sought to contain communism in Latin America, by establishing the Alliance for Progress, which sent aid to troubled countries in the region and sought greater human rights standards in the region. He worked closely with Puerto Rican Governor Luis Muñoz Marín for the development of the Alliance of Progress, as well as developments on the autonomy of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

Another example of Kennedy's belief in the ability of nonmilitary power to improve the world was the creation of the Peace Corps, one of his first acts as president. Through this program, which still exists today, Americans volunteered to help underdeveloped nations in areas such as education, farming, health care, and construction.

Kennedy also used limited military action to contain the spread of communism. Determined to stand firm against the spread of communism, Kennedy continued the previous administration's policy of political, economic, and military support for the unstable South Vietnamese government, which included sending military advisers and U.S. special forces to the area. U.S. involvement in the area continually escalated until regular U.S. forces were directly fighting the Vietnam War in the next administration.

On June 26, 1963 Kennedy visited West Berlin and gave a public speech criticizing communism. While Kennedy was speaking, on the other side of the wall were the people of East Berlin who were applauding Kennedy showing their distaste in Soviet control. Kennedy used the construction of the Berlin Wall as an example of the failures of communism - "Freedom has many difficulties and democracy is not perfect, but we have never had to put a wall up to keep our people in." The speech is known for its famous phrase Ich bin ein Berliner ("I am a Berliner").

Troubled by the long-term dangers of radioactive contamination and nuclear weapons proliferation, Kennedy also pushed for the adoption of a Limited or Partial Test Ban Treaty, which prohibited atomic testing on the ground, in the atmosphere, or underwater, but does not prohibit testing underground. The United States, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union were the initial signatories to the Treaty. Kennedy signed the Treaty into law in August 1963, and believed it to be one of the greatest accomplishments of his administration.

On the occasion of his visit to Ireland in 1963, President Kennedy joined with Irish President Eamon de Valera to form The American Irish Foundation. The mission of this organization was to foster connections between Americans of Irish descent and the country of their ancestry. (See The Ireland Funds)

Domestic policies

JFK in the Oval Office with various civil rights activists including Martin Luther King JrKennedy used the term New Frontier as a label for his domestic program. It ambitiously promised federal funding for education, medical care for the elderly, and government intervention to halt the recession. Kennedy also promised an end to racial discrimination.The turbulent end of state-sanctioned racial discrimination was one of the most pressing domestic issues of Kennedy's era. The U.S. Supreme Court had ruled in 1954 that racial segregation in public schools would no longer be permitted. However, there were many schools, especially in southern states, that did not obey this decision. There also remained the practice of segregation on buses, in restaurants, movie theaters, and other public places.

Thousands of Americans of all races and backgrounds joined together to protest this discrimination. Kennedy supported racial integration and civil rights, and called the jailed Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s wife (Coretta Scott King) during the 1960 campaign, which drew much black support to his candidacy. However, as president, Kennedy initially believed the grassroots movement for civil rights would only anger many Southern whites and make it even more difficult to pass civil rights laws through Congress, which was dominated by Southern Democrats, and he distanced himself from it. As a result, many civil rights leaders viewed Kennedy as unsupportive of their efforts.

President Kennedy had to step in in June 1963, when the Governor of Alabama, George Wallace, blocked the doorway to the University of Alabama to stop two black students, Vivian Malone and James Hood, from enrolling. George Wallace moved aside after being confronted by federal marshals, Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach, and the Alabama National Guard.

Also on the domestic front, in 1963 Kennedy proposed a tax reform that included income tax cuts, but this was not passed by the Congress until after his death in 1964. It is one of the largest tax cuts in modern U.S. history, surpassing the Reagan tax cut of 1981.

Support of space programs

JFK looks at the space craft Friendship 7, the spacecraft that made three earth orbits, piloted by astronaut John Glenn.Kennedy was eager for the United States to lead the way in the space race. The Soviet Union was ahead of the U.S. in its knowledge of space exploration and Kennedy was determined that the U.S. could catch up. He said, "No nation which expects to be the leader of other nations can expect to stay behind in this race for space" and "We choose to go to the Moon and to do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard". Kennedy asked Congress to approve more than twenty two billion dollars for Project Apollo, which had the goal of landing an American man on the Moon before the end of the decade. In 1969, six years after Kennedy's death, this goal was finally realized when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to land on the Moon.Cabinet

Both Kennedy and his wife "Jackie" were very young when compared to earlier presidents and first ladies, and were both extraordinarily popular in ways more common to pop singers and movie stars than politicians, influencing fashion trends and becoming the subjects of numerous photo spreads in popular magazines.The Kennedys brought a new life and vigor to the atmosphere of the White House. They believed that the White House should be a place to celebrate American history, culture, and achievement, and invited artists, writers, scientists, poets, musicians, actors, Nobel Prize winners and athletes to visit. Jacqueline Kennedy also gathered new art and furniture and eventually restored all the rooms in the White House.

The White House also seemed like a more fun, youthful place, because of the Kennedys' two young children, Caroline and John Jr. (who came to be known in the popular press, erroneously, as "John-John"). Outside the White House Lawn, the Kennedys established a pre-school, swimming pool, and tree house.

The Kennedy brothers: John, Robert, and Edward (Ted)Behind the glamorous facade, the Kennedys also suffered many personal tragedies, most notably the death of their newborn son Patrick Bouvier Kennedy in August 1963.

Information revealed after Kennedy's death leaves no doubt that he had many extramarital affairs while in office, including liaisons in the White House with some female staff and visitors. In his era, though, such issues were not considered fit for publication, and in Kennedy's case, they were never publicly discussed during his life, even though there were some public clues of an involvement with Marilyn Monroe, such as the manner in which she sang Happy Birthday Mr. President at his televised birthday party in May 1962. In the years after his death, many liaisons were revealed, including one with Judith Campbell Exner, who was simultaneously involved with Chicago mob boss Sam Giancana.

The "charisma" Kennedy and his family projected posthumously led to the figurative designation of "Camelot" for his administration.

Assassination and aftermath

President Kennedy, Jackie, and Gov. John Connally in the Presidential limousine shortly before the assassination.Main article: John F. Kennedy assassination

President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, on Friday, November 22, 1963 at 12:30 pm CST while on a political trip through Texas. Aldous Huxley and C.S. Lewis both died on the same day as JFK, but because of the assassination, their deaths received little media attention.Lee Harvey Oswald was charged at 7:00 pm for killing a Dallas policeman by "murder with malice", and also charged at 11:30 pm for the "murder" of the president (there being no charge of "assassination" of a president at that time). Oswald was himself fatally shot less than two days later in the basement of the Dallas police station by Jack Ruby. Five days after Oswald was killed, the new president, Lyndon B. Johnson, created the Warren Commission, chaired by Chief Justice Earl Warren, to investigate the assassination.

Legacy and memorials

The world mourned the assassinated presidentTelevision became the primary source by which people kept informed of events surrounding Kennedy's assassination, with newspapers the following day becoming more souveneirs than sources of updated information. U.S. networks switched to 24 hour news coverage for the first time ever. Kennedy's funeral and the murder of Lee Harvey Oswald were all broadcast live in America and in other places around the world. It was with this event that television matured as a news source rivalling that of newspapers.Kennedy's grave at Arlington National Cemetery.On March 14, 1967 Kennedy's body was moved to a permanent burial place and memorial at Arlington National Cemetery. U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson said of the assassination that "all of us...will bear the grief of his death until the day of ours." Kennedy is buried with his wife and their deceased children, and his brother Robert is also buried nearby. His grave is marked with an "Eternal Flame".

Despite his relatively short term in office, and a lack of major legislative changes during his term, Kennedy is seen as one of America's greatest Presidents.

Kennedy's legacy has been memoralized in various aspects of American culture. New York Idlewild International Airport was renamed John F. Kennedy International Airport on December 24, 1963 to honor his memory, and the USS John F. Kennedy was awarded on April 30, 1964 as a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier. The John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library opened in 1979 as Kennedy's official presidential library. John F. Kennedy University opened in Pleasant Hill, California in 1964 as a school for adult education.

As an honorary commemoration, Kennedy's portrait now appears on the United States half dollar coin.

Criticism

Kennedy is among the most popular former Presidents of the United States; however, a number of critics argue that his reputation is largely undeserved. While he was young and charismatic, he had little chance to achieve much during his presidency. Under this reasoning, his immense popularity results from the fact that his short time in office was marked by the optimistic beginnings of many programs declared to be of great benefit to the United States, its people, and various global issues. Unlike the tenures of other U.S. presidents, Kennedy's time in office, generally speaking, thereby lacked the scandals and controversies seen in the terms of many other presidents who served longer. The Civil Rights Act which he sent to Congress in 1963 was, at least in part, conceived by his brother and Attorney-General Robert F. Kennedy, and largely implemented by his successor, Lyndon Johnson, in 1964.Kennedy's personal life has attracted the ire of critics, some of whom argue that lapses in judgment in his personal life impacted his professional life. Many of these criticisms stem from revelations about the extent to which the Kennedy family went to hide his serious, potentially life-threatening health issues (e.g., he suffered from Addison disease) from the voting public, his heavy medication regimen, his long history of extra-marital dalliances, and alleged, circuitous links to organized crime figures. Seymour Hersh's Dark Side of Camelot (1998) presents such a critical argument. Robert Dallek's An Unfinished Life (2003) is a more balanced biography, but contains much detail on Kennedy's health issues.

Another of Kennedy's critics is U.S. intellectual Noam Chomsky, whose book Rethinking Camelot: JFK, the Vietnam War, and US Political Culture (1993) presents an image of the Kennedy administration opposite to the one that lingers in mainstream memory. The book is a criticism of policy rather than his personal life, and explores information not usually presented about the 35th president. In particular, Chomsky and many other critics highlight the ill-planned increased U.S. involvement in the Vietnam conflict under Kennedy's tenure.

John F. Kennedy, whose ancestors came from Ireland, was the first Roman Catholic to become president of the United States. Aged 43 at the time of his election in 1960, he was also the youngest person ever elected to the country's highest office, although he was not the youngest to serve in it. Theodore Roosevelt was not quite 43 when the assassination of President William McKinley in 1901 elevated him to the presidency. Like McKinley, Kennedy was to die at the hands of an assassin.

A confrontation with the Soviet Union in Berlin and the discovery of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba brought the United States close to the brink of war during Kennedy's presidency. His support of demands by blacks for equality in civil rights shook the Democratic Party's long-standing grip on the South and tested his political leadership. Racial integration, economics, and other issues stirred fierce antagonisms throughout the United States. But for millions of Americans, the young president held great charm and even greater hopes, and his violent death in 1963 brought many people to tears.

________________________________________

Early Life

John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born on May 29, 1917, in Brookline, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston, into a family of wealth and strong political tradition. Both his grandfathers, Patrick J. Kennedy and John F. Fitzgerald, had been elected to public offices. Fitzgerald, in fact, had been mayor of Boston and had served in Congress.

Joseph P. Kennedy, father of the future president, was a financier and businessman who built one of the great private fortunes of his time. He was active in politics, too, holding several important posts, including ambassador to Great Britain. He and his wife, Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy, raised a family of nine children. John was the second born.

The family circle was close and warm, although the boys, four in all, were competitive, a trait that would distinguish them all their lives. The slightly built John (or Jack, as he was usually called) was often overshadowed by his older, sturdier brother, Joseph, Jr., who was likeable, outgoing, and aggressive. When Joseph, Jr., was born, his father was reported to have remarked that he would be the first Kennedy to become president.

However, young Joe would be killed while piloting a bomber in World War II, leadership of the new generation of Kennedys passing to John, who would also serve in the war, but survive it. The two younger brothers, Robert and Edward, would also have impressive political careers, although Robert's life, like John's, was to end tragically.

As a boy, Kennedy attended private schools in Brookline and New York City and went on to Choate School, a college preparatory school in Connecticut. Although his father was a graduate of Harvard and his brother Joe was studying at Harvard, John decided to continue his education at Princeton University. Joseph, Sr., kidded John about fleeing his older brother's shadow, but John simply said that he wanted to be with his Choate friends, who were going to Princeton. First, though, at his father's urging, he left for London in the summer of 1935 to attend a session of the London School of Economics. Soon after arriving, however, he came down with jaundice, a liver ailment, and had to return home. He entered Princeton as planned the following fall, but a second attack of jaundice forced him to leave school. He spent months recuperating and the following year re-entered college, this time choosing Harvard.

________________________________________

Young Manhood

Harvard professors found John Kennedy "a pleasant, bright, easygoing student," although his grades were seldom higher than C in his first two years. He worked on the college newspaper and went out for swimming, football, sailing, and other sports. One day, he hurt his back in a junior varsity football game. It was the beginning of a painful injury that would bother him for the rest of his life.

Politics apparently did not concern him at first, but a visit to Europe in the summer of 1937 increased his interest in world affairs. Another trip, this time to Eastern Europe in 1939, sharpened his intellectual interests noticeably. His grades improved dramatically in his senior year, and in 1940, he graduated from Harvard cum laude ("with honor"). World War II had already begun in Europe. Kennedy's senior thesis reflected his earlier observations so well that he turned it into a successful book, Why England Slept. It was his explanation of the inaction of democratic nations in the face of the early threats of war from Nazi Germany.

________________________________________

The War Years

Out of college, Kennedy was uncertain about his future. He thought about attending Yale Law School, went to business school at Stanford University for six months instead, then toured South America. In 1941 he tried to enlist in the Army but was rejected because of his old back injury. After five months of exercise to strengthen his back, he was accepted for service by the Navy.

Kennedy found his assignments, mostly paperwork, dull. When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, he applied for sea duty, underwent torpedo boat training, and was commissioned an ensign. The next year he shipped out for the South Pacific. There he became the central figure in one of the dramatic episodes of the war.

Exploits of PT-109.

In the early hours before dawn on August 2, 1943, Kennedy, now a lieutenant (junior grade), was in command of the torpedo boat PT-109 on patrol near the Solomon Islands. Suddenly a Japanese destroyer plowed through the darkness and cut Kennedy's boat in half. Two of the twelve-man crew disappeared, one was badly burned, and others were less seriously hurt. Kennedy himself was thrown to the deck and his back re-injured, but he gathered his men on the bobbing bow, all that remained of his boat. When it seemed as if the bow would sink, Kennedy ordered everyone to make for an island about 3 miles (5 kilometers) away. Those who could not swim were told to hang onto a plank, once part of the gun mount, and push. Kennedy took charge of the burned crew member, and holding the straps of the man's life vest with his teeth, he towed him to the island.

Kennedy swam to other islands to try to find help but got caught in an ocean current and passed out, only his life vest saving him. Eventually, he and another officer found two natives in a canoe. Scratching a message on a coconut, Kennedy handed it to the natives, who carried it to a U.S. naval base. The men were rescued five days later. For his courage and leadership, Kennedy won the Navy and Marine Corps Medal.

He refused a chance to leave active duty, but malaria and his old back injury finally forced him into the hospital in 1944. After back surgery, he was discharged from the Navy in 1945.

________________________________________

Journalism, Politics, and Marriage

Still searching for a career, Kennedy went to work for the Hearst chain of newspapers. He covered the San Francisco conference that established the United Nations, British elections, and the Potsdam Conference held by the victorious Allied leaders at the end of World War II. Deciding that journalism was not for him, however, Kennedy turned to politics.

In 1946 he ran for the Democratic nomination for the U.S. House of Representatives from a Boston district. By hard campaigning, he defeated a large field of rivals for the nomination and easily won the election. After twice winning re-election, in 1952 he sought and won election to the U.S. Senate.

In 1953, Kennedy married Jacqueline Lee Bouvier in Newport, Rhode Island. They had a daughter, Caroline (1957- ), and a son, John, Jr. (1960-99). Another child, Patrick, was born in 1963 but lived only a few days.

________________________________________

His Congressional Record

Kennedy's record in Congress--six years in the House of Representatives and eight in the Senate--defied easy labeling. His strong liberal streak led him, for instance, to oppose the loyalty oath that college students had to take to get a loan. His support of labor's demands for higher-minimum-wage laws and other welfare benefits also stamped him as a liberal. But when some liberals resisted union reform legislation, Kennedy disagreed. He did not join the anti-union reformers, but took a moderate position. Only a master of the art of politics could, in those days, insist on any union reforms at all and still command the support of labor leaders, as Kennedy did.

The McCarthy Issue.

Kennedy displeased the liberals, however, by failing to take a strong position against McCarthyism. He was in the hospital, suffering from a recurrence of his old back ailment, when the Senate voted on December 2, 1954, to censure (reprimand) its Wisconsin Republican member, Joseph R. McCarthy. McCarthy's methods of investigating Communist influence in the United States during the early 1950's had caused great controversy. It was generally felt that his methods had violated rules of fair play and had unjustly damaged reputations. Liberals, in particular, criticized Kennedy for what they considered evasion of a difficult issue.

________________________________________

Campaign for the Presidency

Kennedy missed being nominated for vice president by a few votes at the National Democratic Convention in Chicago in 1956. But he gained an introduction to the millions of Americans who watched the convention on television, and when he decided to run for president in 1960, his name was widely known. Many people thought that his religion and his youthful appearance would handicap him. Kennedy faced the religion issue frankly, declaring his firm belief in the separation of church and state. He drew some criticism for his family's wealth, which enabled him to assemble a large staff and to get around the country in a private plane. But he attracted many doubting Democratic politicians to his side by winning delegate contests in every state primary he entered.

On gaining his party's nomination, Kennedy amazed nearly everybody by choosing Lyndon B. Johnson, who had opposed him for the nomination, as his vice-presidential running mate. Again, he used his considerable political skills to convince doubting friends that this was the practical course.

Kennedy's four television debates with the Republican candidate, Richard M. Nixon, were a highlight of the 1960 campaign. In the opinion of one television network president, they were "the most significant innovation in Presidential campaigns since popular elections began." The debates were important in Kennedy's victory--303 electoral votes to 219 for Nixon. The popular vote was breathtakingly close: Kennedy's winning margin was a fraction of 1 percent of the total vote.

________________________________________

His Administration

Kennedy's major problems as president were the Cold War with the Soviet Union and its Communist allies, the resistance of southerners in his own party to the demands of blacks for full civil rights, and unemployment. Soon after taking office in 1961, he had to deal with two dangerous confrontations with the Soviet Union.

Berlin.

As if to test the new president's courage, the Soviets chose to make Berlin, the capital of pre-war Germany, a chief battleground of the Cold War. In the summer of 1961, they intensified their pressures on West Berlin, which was under the protection of the United States, Britain, and France and was entirely surrounded by Communist East German territory. Kennedy insisted on the Western Allies' right of access to West Berlin, and when the Communist authorities built a wall separating the city's eastern and western sectors, he responded by increasing U.S. military forces. The Soviet threat subsided in Berlin by 1962 but soon flared elsewhere.

Cuban Missile Crisis.

It struck closer to home, on the island of Cuba. Earlier, in April 1961, a group of Cubans, trained by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), had launched an unsuccessful invasion of the island in an attempt to overthrow the Communist regime of Fidel Castro. Kennedy accepted responsibility for the affair, although its planning had begun under the previous administration of President Dwight Eisenhower. The Cuban issue became far more serious in the fall of 1962, when aerial photographs revealed the presence of Soviet missiles and troops on the island. Kennedy insisted on their withdrawal, proclaiming a naval blockade of the island. The crisis lasted for more than a week, ending when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev agreed to the U.S. demand. See the article on the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Other Foreign Policy Measures.

Relations between the United States and the Soviet Union improved after the end of the Cuban missile crisis, at least on the surface, but Cold War tensions continued. Increased Communist guerrilla activity in South Vietnam and other parts of Southeast Asia led Kennedy to greatly increase the number of U.S. military advisors there. To counter Communist influence in Latin America, he established in 1961 the Alliance for Progress, a program of aid and cooperation between the United States and the countries of the region. A hopeful step was a treaty banning nuclear testing in the atmosphere, signed in 1963, after long and difficult negotiations, by the United States, the Soviet Union, and Britain.

Civil Rights.

The civil rights issue presented the most difficult challenge to the president at home. Demonstrations by blacks in the South for an end to segregation led Kennedy to declare a "moral crisis" and call for legislation providing equal rights for all. When rioting broke out at the University of Mississippi in 1962 over the enrollment of a black, James Meredith, the administration sent federal marshals backed by national guardsmen to the scene to restore order. This resulted in a white anti-Kennedy backlash in the South, directed not only at the president but also at his brother Robert, who was attorney general.

Other Domestic Issues.

Kennedy called his domestic program the New Frontier. Delaying tactics, more than actual rejections, by Congress hampered his record of legislative achievements. His hopes for new civil rights laws and a tax cut to help provide more jobs were unfulfilled at the time of his death. However, Congress did pass the Trade Expansion Act, which enabled the president to lower tariffs, or taxes on imports, to compete with nations of the European Community (now the European Union). One of Kennedy's most popular achievements was the Peace Corps, a volunteer organization that brought education and skills to developing countries of the world. See the article on the Peace Corps.

Kennedy also appointed two new justices to the U.S. Supreme Court, Byron R. White and Arthur J. Goldberg. Goldberg had served as his secretary of labor.

During all this, pain from his old back injury returned. Kennedy wore a small brace and suffered more than the public knew. Yet he loved life and politics. The image of vigor, friendliness, and humor that he gave to the country was real. Even with the burden of the presidency, he found time to read both for information and for pleasure. He wrote two books after he had entered politics, Profiles in Courage in 1956, which won the Pulitzer Prize, and Strategy of Peace in 1960. He had a deep sense of history and an appreciation of scholarship and was able to convey his thoughts in clear, forceful language.

________________________________________

Assassination

On November 22, 1963, Kennedy was in Dallas, Texas, on a political tour of the state. Accompanied by Mrs. Kennedy and Texas governor John B. Connally, he was riding in an open car in a motorcade when shots rang out, striking the president in the head and neck. Kennedy was rushed to the hospital, but he died without regaining consciousness. Reports of his death stunned the nation and the world. A grief-stricken vice president Lyndon Johnson took the oath of office as president on the flight back to Washington, D.C. Meanwhile, police had arrested 24-year-old Lee Harvey Oswald for the murder. Two days later, while being transferred from one jail to another, Oswald himself was shot to death by Jack Ruby, a Dallas nightclub owner.

President Johnson appointed a seven-member commission, headed by U.S. Chief Justice Earl Warren, to investigate the assassination. The resulting Warren Report concluded that Oswald alone had fired the shots that killed the president, although questions surrounding Kennedy's death have continued to arouse speculation ever since. For more information, see the accompanying Wonder Question and the articles Oswald, Lee

Kennedy, John Fitzgerald (1917-1963), 35th president of the United States. The youngest ever elected to the presidency and the first of the Roman Catholic faith, John F. Kennedy won the election of November 1960 by a razor-thin margin, but after taking office he received the support of most Americans. They admired his winning personality, his lively family, his intelligence, and his tireless energy, and they respected his courage in time of decision.

During his relatively brief term of office less than three years President Kennedy dealt with severe challenges in Cuba, Berlin, and elsewhere. A nuclear test ban treaty in 1963 brought about a relaxation in cold war tensions following a time of severe confrontation early in the administration. Domestically, much of the Kennedy program was unfulfilled, brought to fruition only in the Johnson administration. The U.S. space program, however, surged ahead during the Kennedy administration, scoring dramatic gains that benefited American prestige worldwide.

An assassin's bullet cut short Kennedy's term as president. On Nov. 22, 1963, the young president was shot to death while riding in a motorcade in Dallas, Texas. As the nation joined in mourning, dignitaries from around the world gathered at his funeral in Washington to pay their respects. Mayor Willy Brandt of West Berlin expressed the world's sense of loss when he said that "a flame went out for all those who had hoped for a just peace and a better life."

Early Years