Michael D. Robbins © 2002

Astro-Rayological

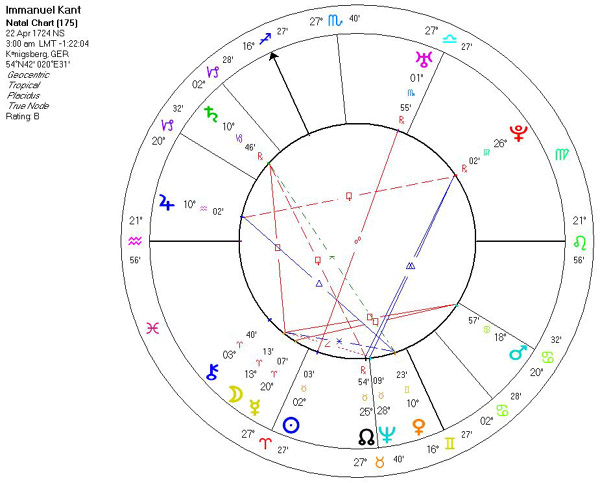

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

All our knowledge begins with the senses, proceeds then to the understanding, and ends with reason. There is nothing higher than reason.

All thought must, directly or indirectly, by way of certain characters, relate ultimately to intuitions, and therefore, with us, to sensibility, because in no other way can an object be given to us.

Always recognize that human individuals are ends, and do not use them as means to your end.

By a lie, a man... annihilates his dignity as a man.

Experience without theory is blind, but theory without experience is mere intellectual play.

Happiness is not an ideal of reason, but of imagination.

If man makes himself a worm he must not complain when he is trodden on.

Immaturity is the incapacity to use one's intelligence without the guidance of another.

In law a man is guilty when he violates the rights of others. In ethics he is guilty if he only thinks of doing so.

Intuition and concepts constitute... the elements of all our knowledge, so that neither concepts without an intuition in some way corresponding to them, nor intuition without concepts, can yield knowledge.

It is not God's will merely that we should be happy, but that we should make ourselves happy

It is not necessary that whilst I live I live happily; but it is necessary that so long as I live I should live honourably.

May you live your life as if the maxim of your actions were to become universal law.

Metaphysics is a dark ocean without shores or lighthouse, strewn with many a philosophic wreck.

Morality is not the doctrine of how we may make ourselves happy, but how we may make ourselves worthy of happiness.

Nothing is divine but what is agreeable to reason.

Science is organized knowledge. Wisdom is organized life.

Seek not the favor of the multitude; it is seldom got by honest and lawful means. But seek the testimony of few; and number not voices, but weigh them.

So act that your principle of action might safely be made a law for the whole world.

To be is to do.

Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing wonder and awe - the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.

What can I know? What ought I to do? What can I hope?Have patience awhile; slanders are not long-lived. Truth is the child of time; erelong she shall appear to vindicate thee.

Science is organized knowledge. Wisdom is organized life.

The history of the human race, viewed as a whole may be regarded as the realization of a hidden plan of nature to bring about a political constitution, internally, and for this purpose, also externally perfect, as the only state in which all the capacities implanted by her in mankind can be fully developed.

Immanuel Kant was born in the East Prussian city of Königsberg, studied at its university, and worked there as a tutor and professor for more than forty years, never travelling more than fifty miles from home. Although his outward life was one of legendary calm and regularity, Kant's intellectual work easily justified his own claim to have effected a Copernican revolution in philosophy. Beginning with his Inaugural Dissertation (1770) on the difference between right- and left-handed spatial orientations, Kant patiently worked out the most comprehensive and influential philosophical programme of the modern era. His central thesis—that the possibility of human knowledge presupposes the active participation of the human mind—is deceptively simple, but the details of its application are notoriously complex.

The monumental Kritik der reinen Vernunft (Critique of Pure Reason) (1781, 1787) fully spells out the conditions for mathematical, scientific, and metaphysical knowledge in its "Transcendental Aesthetic," "Transcendental Analytic," and "Transcendental Dialectic," but Kant found it helpful to offer a less technical exposition of the same themes in the Prolegomena zu einer jeden künftigen Metaphysik die als Wissenschaft wird auftreten können (Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysic) (1783). Carefully distinguishing judgments as analytic or synthetic and as a priori or a posteriori, Kant held that the most interesting and useful varieties of human knowledge rely upon synthetic a priori judgments, which are, in turn, possible only when the mind determines the conditions of its own experience. Thus, it is we who impose the forms of space and time upon all possible sensation in mathematics, and it is we who render all experience coherent as scientific knowledge governed by traditional notions of substance and causality by applying the pure concepts of the understanding to all possible experience. But regulative principles of this sort hold only for the world as we know it, and since metaphysical propositions seek a truth beyond all experience, they cannot be established within the bounds of reason.

Significant applications of these principles are expressed in Metaphysische Anfangsgründe der Naturwissenschaft (Metaphysical Foundations of the Science of Nature) (1786) and Beantwortung der Frage: Ist es eine Erfahrung, daß wir denken? (On Comprehension and Transcendental Consciousness) (1788-1791).

Kant's moral philosophy is developed in the Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten (Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals) (1785). From his analysis of the operation of the human will, Kant derived the necessity of a perfectly universalizable moral law, expressed in a categorical imperative that must be regarded as binding upon every agent. In the Third Section of the Grounding and in the Kritik der practischen Vernunft (Critique of Practical Reason) (1788), Kant grounded this conception of moral autonomy upon our postulation of god, freedom, and immortality.

In later life, Kant drew art and science together under the concept of purpose in the Kritik der Urteilskraft (Critique of Judgment) (1790), considered the consequences of transcendental criticism for theology in Die Religion innerhalb die Grenzen der blossen Vernunft (Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone) (1793), stated the fundamental principles for civil discourse in Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung? ("What is Enlightenment?" (1784), and made an eloquent plea for international cooperation in Zum ewigen Frieden (Perpetual Peace) (1795).

Immanuel Kant was a German philosopher who began in the tradition of Continental rationalism (Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz), was awakened from his dogmatic slumber by Hume's attacks on the rationalist account of causality, and ended by producing a critical philosophy which in some ways synthesizes elements from both the empiricist tradition (Gassendi, Locke, Berkeley and Hume) and the Continental rationalists. At least, this is where Kant placed himself in the picture, whether accurately or not is open to question.

Kant sought to show that some basic principles of science and mathematics which in fact tell us things about the world (and are therefore synthetic, could be known a priori -- that is by intuition alone without experience. While allowing that some synthetic a priori judgements are possible, Kant holds that a good deal of metaphysics which claims to know about the world by reasoning alone is illegitimate. The Kantian system has been enormously influential over the last two centuries.

Kant's ethical works have also had an enormous influence. The distinction between categorical and hypothetical imperatives, the concept of the good will and the idea that ethical judgements should not be made on the basis of the consequences of actions but on whether they are right or not measured by the standard of the categorical imperative have made Kantianism a great contender with Utilitarianism and other ethical systems.

| 1724 | April 22, born in Königsburg, East Prussia, to a family of the pietist sect. |

| 1734 | Enters the Collegium Fredericianum to study theology, excells in the classics. |

| 1740 | Enters the University of Konigsburg and studies mathematics and physics. |

| 1746 | Finishes study at the university and spends the next nine years employed as a private tutor. His father dies. |

| 1755 | Earns his masters degree and lectures at the university for the next fifteen years as a Privatdozent. |

| 1766 | Earns the post of the under-librarian. |

| 1770 | Finally promoted to professorship of logic and metaphysics. |

| 1781 | Publishes Critique of Pure Reason. |

| 1783 | Publishes Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysics. |

| 1785 | Publishes Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals. |

| 1788 | Publishes Critique of Practical Reason. |

| 1790 | Publishes Critique of Judgement. |

| 1792 | Is embroiled with the Government review regarding his religious doctrines and prohibited from lecturing or writing on religious subjects by the king Frederick William II. |

| 1793 | Publishes Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone. |

| 1794 | Withdraws from society but continues his lectures. |

| 1795 | Reduces his lectures to one each week. |

| 1797 | Retires from his post at the university. The death of King Frederick William II removes the ban on his religious writing and lecturing. Publishes Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals. |

| 1798 | Publishes Anthropology, Considered from a Pragmatic Viewpoint. |

| 1804 | February 12, dies in Konigsburg having never travelled more than forty miles from his home town. |

Life

Born in Königsberg (now Kaliningrad, Russia), April 22, 1724, Kant received his education at the Collegium Fredericianum and the University of Königsberg. At the college he studied chiefly the classics, and at the university he studied physics and mathematics. After his father died, he was compelled to halt his university career and earn his living as a private tutor. In 1755, aided by a friend, he resumed his studies and obtained his doctorate. Thereafter, for 15 years he taught at the university, lecturing first on science and mathematics, but gradually enlarging his field of concentration to cover almost all branches of philosophy. Although Kant's lectures and works written during this period established his reputation as an original philosopher, he did not receive a chair at the university until 1770, when he was made professor of logic and metaphysics. For the next 27 years he continued to teach and attracted large numbers of students to Königsberg. Kant's unorthodox religious teachings, which were based on rationalism rather than revelation, brought him into conflict with the government of Prussia, and in 1792 he was forbidden by Frederick William II, king of Prussia, to teach or write on religious subjects. Kant obeyed this order for five years until the death of the king and then felt released from his obligation. In 1798, the year following his retirement from the university, he published a summary of his religious views. He died February 12, 1804.