Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

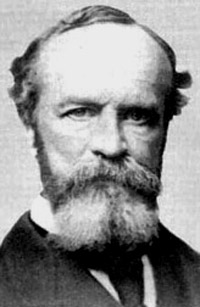

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

A chain is no stronger than its weakest link, and life is after all a chain.

A great many people think they are thinking when they are merely rearranging their prejudices.

A man has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him.

Acceptance of what has happened is the first step to overcoming the consequences of any misfortune.

Action seems to follow feeling, but really action and feeling go together; and by regulating the action, which is under the more direct control of the will, we can indirectly regulate the feeling, which is not.

All natural goods perish. Riches take wings; fame is a breath; love is a cheat; youth and health and pleasure vanish.

An act has no ethical quality whatever unless it be chosen out of several all equally possible.

An idea, to be suggestive, must come to the individual with the force of revelation.

As there is no worse lie than a truth misunderstood by those who hear it, so reasonable arguments, challenges to magnanimity, and appeals to sympathy or justice, are folly when we are dealing with human crocodiles and boa-constrictors.

Be willing to have it so. Acceptance of what has happened is the first step to overcoming the consequences of any misfortune.

Begin to be now what you will be hereafter.

Belief creates the actual fact.

Believe that life is worth living and your belief will help create the fact.

Common sense and a sense of humor are the same thing, moving at different speeds. A sense of humor is just common sense, dancing.

Do every day or two something for no other reason than you would rather not do it, so that when the hour of dire need draws nigh, it may find you not unnerved and untrained to stand the test.

Do something everyday for no other reason than you would rather not do it, so that when the hour of dire need draws nigh, it may find you not unnerved and untrained to stand the test.

Every man who possibly can should force himself to a holiday of a full month in a year, whether he feels like taking it or not.

Everybody should do at least two things each day that he hates to do, just for practice.

Everyone knows that on any given day there are energies slumbering in him which the incitement's of that day do not call forth. Compared with what we ought to be, we are only half awake. The human individual usually lives far within his limits.

Faith means belief in something concerning which doubt is theoretically possible.

Genius... means little more than the faculty of perceiving in an unhabitual way.

Great emergencies and crises show us how much greater our vital resources are than we had supposed.

How to gain, how to keep, how to recover happiness is in fact for most men at all times the secret motive of all they do, and of all they are willing to endure.

Human beings can alter their lives by altering their attitudes of mind.

I will act as if what I do makes a difference.

If any organism fails to fulfill its potentialities, it becomes sick.

If merely 'feeling good' could decide, drunkenness would be the supremely valid human experience.

If the grace of God miraculously operates, it probably operates through the subliminal door.

If you believe that feeling bad or worrying long enough will change a past or future event, then you are residing on another planet with a different reality system.

If you want a quality, act as if you already had it. If you want a trait, act as if you already have the trait.

Individuality is founded in feeling; and the recesses of feeling, the darker, blinder strata of character, are the only places in the world in which we catch real fact in the making, and directly perceive how events happen, and how work is actually done.

Is life worth living? It all depends on the liver.

It is only by risking our persons from one hour to another that we live at all. And often enough our faith beforehand in an uncertified result is the only thing that makes the result come true.

It is our attitude at the beginning of a difficult task which, more than anything else, will affect its successful outcome.

It is well for the world that in most of us, by the age of thirty, the character has set like plaster, and will never soften again.

It is wrong always, everywhere, and for everyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence.

Knowledge about life is one thing; effective occupation of a place in life, with its dynamic currents passing through your being, is another.

Man can alter his life by altering his thinking.

Most people never run far enough on their first wind to find out they've got a second.

No matter how full a reservoir of maxims one may possess, and no matter how good one's sentiments may be, if one has not taken advantage of every concrete opportunity to act, one's character may remain entirely unaffected for the better.

Nothing is so fatiguing as the eternal hanging on of an uncompleted task.

Objective evidence and certitude are doubtless very fine ideals to play with, but where on this moonlit and dream-visited planet are they found?

One hearty laugh together will bring enemies into a closer communion of heart than hours spent on both sides in inward wrestling with the mental demon of uncharitable feeling.

Our errors are surely not such awfully solemn things. In a world where we are so certain to incur them in spite of all our caution, a certain lightness of heart seems healthier than this excessive nervousness on their behalf.

Our esteem for facts has not neutralized in us all religiousness. It is itself almost religious. Our scientific temper is devout.

Our faith is faith in someone else's faith, and in the greatest matters this is most the case.

Our normal waking consciousness, rational consciousness as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different.

Spiritual energy flows in and produces effects in the phenomenal world.

Success or failure depends more upon attitude than upon capacity successful men act as though they have accomplished or are enjoying something. Soon it becomes a reality. Act, look, feel successful, conduct yourself accordingly, and you will be amazed at the positive results.

The art of being wise is the art of knowing what to overlook.

The best argument I know for an immortal life is the existence of a man who deserves one.

The community stagnates without the impulse of the individual. The impulse dies away without the sympathy of the community.

The deepest principle in human nature is the craving to be appreciated.

The essence of genius is to know what to overlook.

The exclusive worship of the bitch-goddess Success is our national disease.

The god whom science recognizes must be a God of universal laws exclusively, a God who does a wholesale, not a retail business. He cannot accommodate his processes to the convenience of individuals.

The greatest discovery of my generation is that a human being can alter his life by altering his attitudes.

The greatest enemy of any one of our truths may be the rest of our truths.

The greatest use of a life is to spend it on something that will outlast it.

The hell to be endured hereafter, of which theology tells, is no worse than the hell we make for ourselves in this world by habitually fashioned our characters in the wrong way.

The ideas gained by men before they are twenty-five are practically the only ideas they shall have in their lives.

The sovereign cure for worry is prayer.

The sway of alcohol over mankind is unquestionably due to its power to stimulate the mystical faculties of human nature, usually crushed to earth by the cold facts and dry criticisms of the sober hour.

The world we see that seems so insane is the result of a belief system that is not working. To perceive the world differently, we must be willing to change our belief system, let the past slip away, expand our sense of now, and dissolve the fear in our minds.

There is but one cause of human failure. And that is man's lack of faith in his true Self.

There is no more miserable human being than one in whom nothing is habitual but indecision, and for whom the lighting of every cigar, the drinking of every cup, the time of rising and going to bed every day, and the beginning of every bit of work, are subjects of express volitional deliberation.

There is only one thing a philosopher can be relied upon to do, and that is to contradict other philosophers.

This life is worth living, we can say, since it is what we make it.

To change ones life: Start immediately. Do it flamboyantly.

To spend life for something which outlasts it.

To study the abnormal is the best way of understanding the normal.

We are all ready to be savage in some cause. The difference between a good man and a bad one is the choice of the cause.

We are doomed to cling to a life even while we find it unendurable.

We can act as if there were a God; feel as if we were free; consider Nature as if she were full of special designs; lay plans as if we were to be immortal; and we find then that these words do make a genuine difference in our moral life.

We don't laugh because we're happy - we're happy because we laugh.

We have grown literally afraid to be poor. We despise anyone who elects to be poor in order to simplify and save his inner life. If he does not join the general scramble and pant with the money-making street, we deem him spiritless and lacking in ambition.

We have to live today by what truth we can get today and be ready tomorrow to call it falsehood.

We never fully grasp the import of any true statement until we have a clear notion of what the opposite untrue statement would be.

Whatever universe a professor believes in must at any rate be a universe that lends itself to lengthy discourse. A universe definable in two sentences is something for which the professorial intellect has no use. No faith in anything of that cheap kind!

When you have to make a choice and don't make it, that is in itself a choice.

Whenever you're in conflict with someone, there is one factor that can make the difference between damaging your relationship and deepening it. That factor is attitude.

Where quality is the thing sought after, the thing of supreme quality is cheap, whatever the price one has to pay for it.

Why should we think upon things that are lovely? Because thinking determines life. It is a common habit to blame life upon the environment. Environment modifies life but does not govern life. The soul is stronger than its surroundings.

Wisdom is learning what to overlook.

was an original thinker in and between the disciplines of physiology, psychology and philosophy. His twelve-hundred page masterwork, The Principles of Psychology (1890), is a rich blend of physiology, psychology, philosophy, and personal reflection that has given us such ideas as "the stream of thought" and the baby's impression of the world "as one great blooming, buzzing confusion" (PP 462). It contains seeds of pragmatism and phenomenology, and influenced generations of thinkers in Europe and America, including Edmund Husserl, Bertrand Russell, John Dewey, and Ludwig Wittgenstein. James studied at Harvard's Lawrence Scientific School and the School of Medicine, but his writings were from the first as much philosophical as scientific. "Some Remarks on Spencer's Notion of Mind as Correspondence" (1878) and "The Sentiment of Rationality" (1879, 1882) presage his future pragmatism and pluralism, and contain the first statements of his view that philosophical theories are reflections of a philosopher's temperament or vision.

James hints at his religious concerns in his earliest essays and in The Principles, but they become more explicit in The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy (1897), Human Immortality: Two Supposed Objections to the Doctrine (1898), The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) and A Pluralistic Universe (1909). James oscillated between thinking that a "study in human nature" such as Varieties could contribute to a "Science of Religion" and the belief that religious experience involves an altogether supernatural domain, somehow inaccessible to science but accessible to the individual human subject. James made some of his most important philosophical contributions in the last decade of his life. In a burst of writing in 1904-5 (collected in Essays in Radical Empiricism (1912)) he set out the metaphysical view most commonly known as "neutral monism," according to which there is one fundamental "stuff" which is neither material nor mental. He also published Pragmatism (1907), the culminating expression of a set of views permeating his writings.

• Chronology of James's Life

Chronology of James's Life

• 1842. Born in New York City, first child of Henry James and Mary Walsh. James. Educated by tutors and at private schools in New York.

• 1843. Brother Henry born.

• 1848. Sister Alice born.

• 1855-8. Family moves to Europe. William attends school in Geneva, Paris, and Boulogne-sur-Mer; develops interests in painting and science.

• 1858. Family settles in Newport, Rhode Island, where James studies painting with William Hunt.

• 1859-60. Family settles in Geneva, where William studies science at Geneva Academy; then returns to Newport when William decides he wishes to resume his study of painting.

• 1861. William abandons painting and enters Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard.

• 1864. Enters Harvard School of Medicine.

• 1865. Joins Amazon expedition of his teacher Louis Agassiz, contracts a mild form of smallpox, recovers and travels up the Amazon, collecting specimens for Agassiz's zoological museum at Harvard.

• 1866. Returns to medical school. Suffers eye strain, back problems, and suicidal depression in the fall.

• 1867-8. Travels to Europe for health and education: Dresden, Bad Teplitz, Berlin, Geneva, Paris. Studies physiology at Berlin University, reads philosophy, psychology and physiology (Wundt, Kant, Lessing, Goethe, Schiller, Renan, Renouvier).

• 1869. Receives M. D. degree, but never practices. Severe depression in the fall.

• 1870-1. Depression and poor health continue.

• 1872. Accepts offer from President Eliot of Harvard to teach undergraduate course in comparative physiology.

• 1873. Accepts an appointment to teach full year of anatomy and physiology, but postpones teaching for a year to travel in Europe.

• 1874-5. Begins teaching psychology; establishes first American psychology laboratory.

• 1878. Marries Alice Howe Gibbens. Publishes "Remarks on Spencer's Definition of Mind as Correspondence" in Journal of Speculative Philosophy.

• 1879. Publishes "The Sentiment of Rationality" in Mind.

• 1880. Appointed Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Harvard. Continues to teach psychology.

• 1882. Travels to Europe. Meets with Ewald Hering, Carl Stumpf, Ernst Mach, Wilhelm Wundt, Joseph Delboeuf, Jean Charcot, George Croom Robertson, Shadworth Hodgson, Leslie Stephen.

• 1884. Lectures on "The Dilemma of Determinism" and publishes "On Some Omissions of Introspective Psychology" in Mind.

• 1885-92. Teaches psychology and philosophy at Harvard: logic, ethics, English empirical philosophy, psychological research.

• 1890. Publishes The Principles of Psychology with Henry Holt of Boston, twelve years after agreeing to write it.

• 1897. Publishes The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy. Lectures on "Human Immortality" (published in 1898).

• 1898. Identifies himself as a pragmatist in "Philosophical Conceptions and Practical Results," given at the University of California, Berkeley. Develops heart problems.

• 1899. Publishes Talks to Teachers on Psychology: and to Students on Some of Life's Ideals (including "On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings" and "What Makes Life Worth Living?"). Becomes active member of the Anti-Imperialist League, opposing U. S. policy in Philippines.

• 1901-2. Delivers Gifford lectures on "The Varieties of Religious Experience" in Edinburgh (published in 1902).

• 1904-5 Publishes "Does ‘Consciousness’ Exist?," "A World of Pure Experience," "How Two Minds Can Know the Same Thing," "Is Radical Empiricism Solipsistic?" and "The Place of Affectional Facts in a World of Pure Experience" in Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods. All were reprinted in Essays in Radical Empiricism (1912).

• 1907. Resigns Harvard professorship. Publishes Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking, based on lectures given in Boston and at Columbia.

• 1909. Publishes A Pluralistic Universe, based on Hibbert Lectures delivered in England and at Harvard the previous year.

• 1910. Publishes "A Pluralistic Mystic" in Hibbert Journal. Abandons attempt to complete a "system" of philosophy. (His partially completed manuscript published posthumously as Some Problems of Philosophy). Dies of heart failure at summer home in Chocorua, New Hampshire.

Early Writings

"Remarks on Spencer's Definition of Mind as Correspondence" (1878)James's discussion of Herbert Spencer broaches what will turn out to be characteristic Jamesean themes: the importance of religion and the passions, the variety of human responses to life, and the idea that we help to "create" the truths that we "register" (E, 21). Taking up Spencer's view that the adjustment of the organism to the environment is the basic feature of mental evolution, James charges that Spencer projects his own vision of what ought to be onto the phenomena he claims to describe. Survival, James asserts, is merely one of many interests human beings have: "The social affections, all the various forms of play, the thrilling intimations of art, the delights of philosophic contemplation, the rest of religious emotion, the joy of moral self-approbation, the charm of fancy and of wit -- some or all of these are absolutely required to make the notion of mere existence tolerable;..." (E, 13). We are all teleological creatures at base, James holds, each with his or her or own a priori values and categories. Spencer, then, "merely takes sides with the telos he happens to prefer" (E, 18).

James's fundamental empiricism is expressed in the claim that these values and categories fight it out in the course of human experience, that their conflicts "can only be solved ambulando, and not by any a priori definition." The "formula which proves to have the most massive destiny," he concludes, "will be the true one" (E, 17). Yet James wishes to defend his sense that any such formulation will be determined as much by a freely-acting human mind as by the world, a position he would later (in Pragmatism) call "humanism": "there belongs to mind, from its birth upward, a spontaneity, a vote. It is in the game, and not a mere looker-on; and its judgments of the should-be, its ideals, cannot be peeled off from the body of the cogitandum as if they were excrescences..." (E, 21).

"The Sentiment of Rationality" (1879, 82)

This essay was first published in Mind in 1879; a second part appeared in the Princeton Review in 1882. Both parts were used to construct the essay of this title published in The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy (1897). Although he never quite says that rationality is a sentiment, James holds that a sentiment -- really a set of sentiments -- is a "mark" of rationality. The philosopher, James writes, will recognize the rationality of a conception "as he recognizes everything else, by certain subjective marks with which it affects him. When he gets the marks, he may know that he has got the rationality." These marks include a "strong feeling of ease, peace, rest" (WB 57), and a "feeling of the sufficiency of the present moment, of its absoluteness" (WB 58). "Fluid" thinking, whether logical or cosmological, is said to produce the sentiment, as when we learn that the "the balloon rises by the same law whereby the stone sinks" (WB 59). However, balancing the "passion for parsimony" (WB 58) such unifications satisfy is a passion for distinguishing: a "loyalty to clearness and integrity of perception, dislike of blurred outlines, of vague identifications" (WB 59). The ideal philosopher is a blend of these two passions of rationality, and James thinks that even some great philosophers go too far in one direction or another. Spinoza's unity of all things in one substance is "barren,"; and so is Hume's "’looseness and separateness’ of everything..." (WB 60).Sentiments of rationality operate not just in logic or science, but in ordinary life. When we first move into a room, for example, "we do not know what draughts may blow in upon our back, what doors may open, what forms may enter, what interesting objects may be found in cupboards and corners." These uncertainties, minor as they may be, act as "mental irritant[s]" (WB 67-8), which disappear when we know our way around the room and come to "feel at home" there. These feelings of confident expectation, of knowing how certain things will turn out, are another form of the sentiment of rationality.

James begins the second part of his essay by considering the case when "two conceptions [are] equally fit to satisfy the logical demand" for fluency or unification. In such a case, one must consider a "practical" component of rationality: "the one which awakens the active impulses, or satisfies other aesthetic demands better than the other, will be accounted the more rational conception, and will deservedly prevail" (WB 66). James here puts the point as one of psychology -- a prediction of what will prevail -- but he also evaluates it, for it will prevail "deservedly." James rejects reductive materialism because it denies to "our most intimate powers...all relevancy in universal affairs" (WB 71), and hence fails to activate these impulses or satisfy these demands.

As in his essay on Spencer, James continues to explore the relations between the temperament that forms the philosopher's outlook and the outlook itself: "Idealism will be chosen by a man of one emotional constitution, materialism by another." James's empathetic understanding extends to both: idealism offers a sense of intimacy with the universe, the feeling that ultimately I "am all." But people of contrasting temperaments find in idealism "a narrow, close, sick-room air," leaving out an element of danger, contingency and wildness -- "the rough, harsh, sea-wave, north-wind element" (WB 75). Both the intimacy and the wildness answer to propensities, passions, and powers in human beings. Although James has his criticisms of reductive materialisms, he understands -- from the inside as it were -- some of the materialistic passion. Those with a materialistic temperament, he writes, "sicken at a life wholly constituted of intimacy," and have a desire "to escape personality, to revel in the action of forces that have no respect for our ego, to let the tides flow, even though they flow over us." The "strife" of these two forms of "mental temper," James predicts, will always be seen in philosophy (WB 76). Certainly they are always seen in the philosophy of .

The Principles of Psychology

James's masterwork officially follows the psychological method of introspection, defined as follows: "it means, of course, the looking into our own minds and reporting what we there discover" (PP 185). James is thinking in part of the experiments his contemporaries Wundt, Stumpf and Fechner were performing in their laboratories, which led them to results such as that "sounds are less delicately discriminated in intensity than lights" (PP 513). Although James does discuss these results in detail, many of his most important and memorable introspective observations come from his everyday experience. For example:The rhythm of a lost word may be there without a sound to clothe it....Everyone must know the tantalizing effect of the blank rhythm of some forgotten verse, restlessly dancing in one's mind, striving to be filled out with words (PP 244).

Our father and mother, our wife and babes, are bone of our bone and flesh of our flesh. When they die, a part of our very selves is gone. If they do anything wrong, it is our shame. If they are insulted, our anger flashes forth as readily as if we stood in their place. (PP 280).

There is an excitement during the crying fit which is not without a certain pungent pleasure of its own; but it would take a genius for felicity to discover any dash of redeeming quality in the feeling of dry and shrunken sorrow (PP, p. 1061).

"Will you or won't you have it so?" is the most probing question we are ever asked; we are asked it every hour of the day, and about the largest as well as the smallest, the most theoretical as well as the most practical, things. We answer by consents or non-consents and not by words. What wonder that these dumb responses should seem our deepest organs of communication with the nature of things! (PP, p. 1182).

In this last quotation, James tackles a philosophical problem from a psychological perspective. Although he refrains from answering the question of whether these "responses" are in fact deep organs of communication with the nature of things -- reporting only that they seem to us to be so -- in his later writings, such as Varieties of Religious Experience, and A Pluralistic Universe, he confesses, and to some degree defends, his belief that the question should be answered affirmatively.

In the deservedly famous chapter on "The Stream of Thought" James takes himself to be offering a richer account of experience than those of traditional empiricists such as Hume. He believes relations, vague fringes, and tendencies are as experienced directly (he would later label this fact part of his "radical empiricism.") Rather than a succession of "ideas," James finds a stream, the waters of which blend; and where, because of its position in the flow, each situation is unique. Our consciousness -- or, as he prefers to call it sometimes, our "sciousness" -- , is "steeped and dyed" in the waters of sciousness or thought that surround it. Our psychic life not only has edges, it has rhythm: it is a series of transitions and resting-places, of "flights and perchings" (PP 236). We rest when we remember the name we have been searching for; and we are off again when we hear a noise that might be the baby waking from her nap.

Interest -- and its close relative, attention -- is a major component not only of James's psychology, but of the epistemology and metaphysics that seep into his discussion. A thing, James states in "The Stream of Thought," is a group of qualities "which happen practically or aesthetically to interest us, to which we therefore give substantive names.... (PP 274). And reality "means simply relation to our emotional and active life...whatever excites and stimulates our interest is real " (PP 924).

Our capacity for attention to one thing rather than another is for James the sign of an "active element in all consciousness,...a spiritual something...which seems to go out to meet these qualities and contents, whilst they seem to come in to be received by it." (PP 285). This "spiritual something" is the target of another passage from James's chapter on "Attention," where he speaks of "a star performer" or "original psychic force" which takes the form not of mere attention, but of "the effort to attend." According to James's revisionary account of freedom, we are mostly not free, but we achieve freedom in cases which settle, for a while, the direction or orientation of our lives. In these cases we feel the "sting and excitement of our voluntary life," and we sense that "things are really being decided..." (PP, 429). Faced with the tension between scientific determinism and our belief in our own freedom or autonomy, James restricts the claims of science, which "must be constantly reminded that her purposes are not the only purposes, and that the order of uniform causation which she has use for, and is therefore right in postulating, may be enveloped in a wider order, on which she has no claims at all" (PP, 1179).

The Principles thus encompasses several metaphysical and methodological stances. James often writes as a scientist, as befits his education in biology and medicine. The second and third chapters are entitled "The Functions of the Brain" and "On Some General Conditions of Brain Activity." James alleges that habit, the subject of the fourth chapter, is "at bottom a physical principle" (PP 110). Yet, James presents himself -- as in his title -- as a psychologist, not as a physiologist. The method of the psychologist "first last and always" is introspection, which sometimes reveals a personal, traditionally subjective stream of thought, but which, as practiced by James, anticipates phenomenology in its pursuit of a more "pure" description of the stream of thought that does not presuppose it to be mental or material. One such passage concerns a child newly born in Boston, who gets a sensation from the candle-flame which lights the bedroom, or from his diaper-pin [who] does not feel either of these objects to be situated in longitude 71 W. and latitude 42 N.....The flame fills its own place, the pain fills its own place; but as yet these places are neither identified with, nor discriminated from, any other places. That comes later. For the places thus first sensibly known are elements of the child's space-world which remain with him all his life" (PP 681-2).

This passage, taking off from sensations, is rooted in James's empiricism, but it operates as a counter to traditional empiricism, for which "all our sensations at first appear to us as subjective or internal, and are afterwards and by a special act on our part ‘extradited’ or ‘projected’ so as to appear located in an outer world" (PP 678). In contrast, James's view is that the outer and inner worlds are later constructions from the original data of consciousness -- which are neither objective nor subjective. This psychological view anticipates James's late metaphysical "pure experience" account, published in Essays in Radical Empiricism.

Two noteworthy chapters late in The Principles are entitled "The Emotions" and "Will." The first sets out the theory -- also enunciated by the Danish physiologist Carl Lange -- that emotion follows, rather than causes, its bodily expression: "Common-sense says, we lose our fortune, are sorry and weep; we meet a bear, are frightened and run; we are insulted by a rival, are angry and strike. The hypothesis here to be defended says that this order of sequence is incorrect...that we feel sorry because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble....." (PP, pp. 1065-6). The significance of this view, according to James, is that our emotions are tied in with our bodily expressions. What, he asks, would grief be "without its tears, its sobs, its suffocation of the heart, its pang in the breast-bone?" Not an emotion, James answers, for a "purely disembodied human emotion is a nonentity" (PP 1068). As Wittgenstein was to suggest, the human body may be "the best picture of the human soul" (Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, New York, Macmillan, 1968, p. 178).

In his chapter on "Will" James opposes the theory of his contemporary Wilhelm Wundt that there is one special feeling -- a "feeling of innervation" -- present in all intentional action. In his survey of a range of cases, James finds that some actions involve an act of resolve or of outgoing nervous energy, but others do not. For example: I sit at table after dinner and find myself from time to time taking nuts or raisins out of the dish and eating them. My dinner properly is over, and in the heat of the conversation I am hardly aware of what I do; but the perception of the fruit, and the fleeting notion that I may eat it, seem fatally to bring the act about. There is certainly no express fiat here;..." (PP 1131).

The chapter on "Will" also contains striking passages that anticipate the concerns of The Varieties of Religious Experience: about moods, "changes of heart," and "awakenings of conscience." These, James observes, may affect the "whole scale of values of our motives and impulses (PP 1140).

The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular PhilosophyThis popular and influential collection includes "The Sentiment of Rationality" (discussed above), and essays on "The Dilemma of Determinism," "Great Men and Their Environment" and "Is Life Worth Living?" Its most famous essay gives the collection its title, although James later wrote that he should have called the essay "the right to believe," indicating his justificatory intent.

In science, James notes, we can afford to await the outcome of investigation before coming to a belief. The cases of belief formation and justification to which James draws attention in "The Will to Believe" are, in contrast, "forced" -- we must come to some belief even if all the relevant evidence is not in. If I am on a mountain trail, faced with an icy ledge to cross, and do not know whether I can make it, I may be forced to consider the question whether I can or should believe that I can cross the ledge. This is a "momentous" question: if I am wrong I may fall to my death, and if I believe rightly that I can cross the ledge, my holding of the belief may itself contribute to my success. In such a case, James asserts, I have the "right to believe" -- precisely because such a belief may help bring about the fact believed in. This is a case "where a fact cannot come at all unless a preliminary faith exists in its coming" (WB 25).

James applies his analysis to religious belief, particularly to the possible case in which one's salvation depends on believing in God in advance of any proof that God exists. In such a case the belief may be justified by the outcome to which having the belief leads. James also takes his analysis outside of the religious domain, to a wide range of secular human life:

A social organism of any sort is what it is because each member proceeds to his own duty with a trust that the other members will simultaneously do theirs.... A government, an army, a commercial system, a ship, a college, an athletic team, all exist on this condition, without which not only is nothing achieved, but nothing is even attempted (WB, 24).

James tries to justify the systems of "trust" on which society's beliefs and actions are based. Yet at the same time there is an intensely personal, even existential, tone to his essay, epitomized by James's appeal near the end to "respect one another's mental freedom," and by his concluding citation of Fitz James Stephen's statement that "‘In all important transactions of life we have to take a leap in the dark....’"( WB 31).

Another essay in the collection, "Reflex Action and Theism," attempts a reconciliation of science and religion. By "reflex action" James understands the biological picture of the organism as responding to sensations with a series of actions. Human beings and other higher animals have evolved a theoretical or thinking stage between the sensation and the action, and it is here that God comes up, at least for human beings. James holds that the thought of God is a natural human response to the universe, regardless of whether we can prove that God exists. God will be, as James puts it, the "centre of gravity of all attempts to solve the riddle of life" (WB, 116). James ends the essay by advocating a "theism" that posits "an ultimate opacity in things, a dimension of being which escapes our theoretic control" (WB, 143).

The Will to Believe also contains James's most developed account of morality, "The Moral Philosopher and the Moral Life." Morality for James rests on sentience -- without it there are no moral claims and no moral obligations. But once sentience exists, a claim is made, and morality gets "a foothold in the universe" (WB 198). Although James insists that there is no common essence to morality, he does find a guiding principle for ethical philosophy in the principle that we "satisfy at all times as many demands as we can" (WB, 205). This satisfaction is to be arrived at by working towards a "richer universe...the good which seems most organizable, most fit to enter into complex combinations, most apt to be a member of a more inclusive whole" (WB, 210). We arrive at laws and moral formulations by a kind of "experiment," James holds. (WB, 206). By such experiments, we have liberated ourselves for the most part from slavery and "arbitrary royal power" (WB, 205). But there is nothing final about the results: "as our present laws and customs have fought and conquered other past ones, so they will in their turn be overthrown by any newly discovered order which will hush up the complaints that they still give rise to, without producing others louder still" (WB, 206).

The Varieties of Religious Experience

Like The Principles of Psychology, Varieties is "A Study in Human Nature," as its subtitle says. But at some five hundred pages it is only half the length of The Principles of Psychology, befitting its more restricted, if still immense, scope. For James studies that part of human nature that is, or is related to, religious experience. His interest is not in religious institutions, ritual, or, even for the most part, religious ideas, but in "the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider the divine" (V, 31).James sets out a central distinction of the book in early chapters on "The Religion of Healthy-Mindedness" and "The Sick Soul." The healthy-minded religious person -- Walt Whitman is one of James's main examples -- has a deep sense of "the goodness of life," (79) and a soul of "sky-blue tint" (80). Healthy-mindedness can be involuntary, just natural to someone, but often comes in more willful forms. Liberal Christianity, for example, represents the triumph of a resolute devotion to healthy-mindedness over a morbid "old hell-fire theology" (91). James also cites the "mind-cure movement" of Mary Baker Eddy, for whom "evil is simply a lie, and any one who mentions it is a liar" (107). This remark allows us to draw the contrast with the religion of "The Sick Soul," for whom evil cannot be eliminated. From the perspective of the sick soul, "radical evil gets its innings" (163). No matter how secure one may feel, the sick soul finds that "[u]nsuspectedly from the bottom of every fountain of pleasure, as the old poet said, something bitter rises up: a touch of nausea, a falling dead of the delight, a whiff of melancholy...." These states are not simply unpleasant sensations, for they bring "a feeling of coming from a deeper region and often have an appalling convincingness" (136). James's main examples here are Leo Tolstoy's "My Confession," John Bunyan's autobiography, and a report of terrifying "dread" -- allegedly from a French correspondent but actually from James himself. Some sick souls never get well, while others recover or even triumph: these are "twice-born." In chapters on "The Divided Self, and the Process of Its Unification" and on "Conversion," James discusses St. Augustine, Henry Alline, Bunyan, Tolstoy, and a range of popular evangelists, focusing on what he calls "the state of assurance" (241) they achieve. Central to this state is "the loss of all the worry, the sense that all is ultimately well with one, the peace, the harmony, the willingness to be, even though the outer conditions should remain the same" (248).

Varieties' classic chapter on "Mysticism" offers "four marks which, when an experience has them, may justify us in calling it mystical..." (380). The first is ineffability: "it defies expression...its quality must be directly experienced; it cannot be imparted or transferred to others." Second is a "noetic quality": mystical states present themselves as states of knowledge. Thirdly, mystical states are transient; and, fourth, subjects are passive with respect to them: they cannot control their coming and going. Are these states, James ends the chapter by asking, "windows through which the mind looks out upon a more extensive and inclusive world[?]" (428).

In chapters entitled "Philosophy" -- devoted in large part to pragmatism -- and "Conclusions," James finds that religious experience is on the whole useful, even "amongst the most important biological functions of mankind," but he concedes that this does not make it true. James articulates his own belief -- which he does not claim to prove -- that religious experiences connect us with a greater, or further, reality not accessible in our normal cognitive relations to the world: "The further limits of our being plunge, it seems to me, into an altogether other dimension of existence from the sensible and merely ‘understandable’ world" (515).

Late Writings

Pragmatism (1907)

James first announced his commitment to pragmatism in a lecture given at Berkeley in 1898, entitled "Philosophical Conceptions and Practical Results." Other sources for Pragmatism were lectures given at Wellesley College in 1905, and at the Lowell Institute and Columbia University in 1906 and 1907. Pragmatism emerges in James's book as five things: a philosophical temperament, a theory of truth, a theory of meaning, a holistic account of knowledge, and a method of resolving philosophical disputes.The pragmatic temperament appears in the book's opening chapter, where James classifies philosophers according to their tough-or tender-mindedness. The pragmatist is a mediator like James himself, someone with "scientific loyalty to facts" as well as "the old confidence in human values and the resultant spontaneity, whether of the religious or romantic type" (P, 17). The method of resolving disputes and the theory of meaning are on display in James's discussion of an argument about whether a man chasing a squirrel around a tree goes around the squirrel too. Taking meaning as the "conceivable effects of a practical kind the object may involve," the pragmatist philosopher finds that two "practical" meanings of "go around" are in play: either the man goes North, East, South, and West of the squirrel, or he faces first the squirrel's head, then one of his sides, then his tail, then his other side. "Make the distinction," James writes, "and there is no occasion for any further dispute."

The pragmatic theory of truth is the subject of the book's sixth (and to some degree its second) chapter. Truth, James holds, is "a species of the good," like health. Truths are goods because we can "ride" on them into the future without being unpleasantly surprised. They "lead us into useful verbal and conceptual quarters as well as directly up to useful sensible termini. They lead to consistency, stability and flowing human intercourse. They lead away from excentricity and isolation, from foiled and barren thinking" (103). James holds that truths are "made" (104) in the course of human experience; yet although they live for the most part "on a credit system" in that they are not currently being verified by most of those who have them, "beliefs verified concretely by somebody are the posts of the whole superstructure" (P, 100).

James's chapter on "Pragmatism and Humanism" sets out James's voluntaristic epistemology. "We carve out everything," he states, "just as we carve out constellations, to serve our human purposes" (P, 100). Nevertheless, he recognizes "resisting factors in every experience of truth-making" (P, 117), including not only our present sensations or experiences but the whole body of our prior beliefs. James holds neither that we create our truths out of nothing, nor that truth is entirely independent of humanity. He embraces "the humanistic principle: you can't weed out the human contribution" (P, 122). Pragmatism's final chapter on "Pragmatism and Religion" follows James's line in Varieties in attacking "transcendental absolutism" for its unverifiable account of God, and in defending a "pluralistic and moralistic religion" (144) based on human experience. "On pragmatistic principles," James writes, "if the hypothesis of God works satisfactorily in the widest sense of the word, it is true" (143).

A Pluralistic Universe (1909)

Originally delivered in Oxford as a set of lectures "On the Present Situation in Philosophy," James's book begin with a discussion of philosophic temperament. He condemns the "over-technicality and consequent dreariness of the younger disciples at our American universities..." (PU 13), and holds that a philosopher's "vision" is "the important thing" about him (PU 3). Passing from critical discussions of Royce's idealism and the "vicious intellectualism" of Hegel, James comes, in chapters four through six, to philosophers whose vision he admires. He praises Gustav Fechner for holding that "the whole universe in its different spans and wave-lengths, exclusions and developments, is everywhere alive and conscious" (PU, 70), and he seeks to refine and justify Fechner's idea that separate human, animal and vegetable consciousnesses meet or merge in a "consciousness of still wider scope" (72). James employs Henri Bergson's critique of "intellectualism" in this project, for Bergson shows that the "concrete pulses of experience appear pent in by no such definite limits as our conceptual substitutes are confined by. They run into one another continuously and seem to interpenetrate" (PU 127). James concludes by embracing a position that he had more tentatively set forth in The Varieties of Religious Experience: that religious experiences "point with reasonable probability to the continuity of our consciousness with a wider spiritual environment from which the ordinary prudential man (who is the only man that scientific psychology, so called, takes cognizance of) is shut off" (PU, 135). Whereas in Pragmatism James subsumes the religious within the pragmatic (as yet another way of successfully making one's way through the world), in A Pluralistic Universe, James distinguishes the religious from the "prudential" or "practical."Essays in Radical Empiricism (1912)

James's radical empiricism, which is basically an epistemological doctrine, has been confused with the metaphysical doctrine of "pure experience," largely because the latter is set forth in most of the essays collected after James's death in Essays in Radical Empiricism. Radical empiricism is never precisely defined in the Essays, being best explicated by a passage from The Meaning of Truth in which James states that it consists of a postulate, a statement of fact, and a conclusion. The postulate is that "the only things that shall be debatable among philosophers shall be things definable in terms drawn from experience," the fact is that relations are just as directly experienced as the things they relate, and the conclusion is that "the parts of experience hold together from next to next by relations that are themselves parts of experience" (MT, 6-7).James's "pure experience" doctrine is the view that Bertrand Russell -- giving full credit to James in The Analysis of Mind -- calls "neutral monism." James holds that mind and matter are both aspects of, or structures formed from, a more fundamental stuff -- pure experience -- that (despite being called "experience") is neither mental nor physical. Pure experience, James explains, is "the immediate flux of life which furnishes the material to our later reflection with its conceptual categories... a that which is not yet any definite what, tho' ready to be all sorts of whats..." (ERE, 46). That "whats" pure experience may be include minds and bodies, people and material objects. The "what" of pure experience depends not on a fundamental ontological difference among experiences, but on the relations into which pure experiences enter. Certain sequences of pure experiences constitute physical objects, and others constitute persons; but one pure experience (say the perception of a chair) may be part both of the sequence constituting the chair and of the sequence constituting a person.

(January 11, 1842, New York - August 26, 1910, Chocorua, New Hampshire). Philosopher and psychologist. was born in New York, son of Henry James, Sr., an independently wealthy and notoriously eccentric Swedenborgian theologian well acquainted with the literary and intellectual elites of his day. The intellectual brilliance of the James family milieu and the remarkable epistolary talents of several of its members have, since the 1930s, made it a subject of continuing interest to historians, biographers, and critics.

Early years

(like his younger brother, Henry James, one of the important novelists of the nineteenth century) received an eclectic trans-Atlantic education, thanks in large part to his fluency in both German and French. His early artistic bent led to an early apprenticeship in the studio of William Morris Hunt in Newport, Rhode Island, but yielded in 1861 to scientific studies at Harvard University's Lawrence Scientific School.In his early adulthood, James suffered from a variety of physical and mental difficulties, including problems with his eyes, back, stomach, and skin, as well as periods of depression in which he was tempted by the thought of suicide. Two younger brothers, Garth Wilkinson (Wilky) and Robertson (Bob), fought in the Civil War, but the other three siblings (William, Henry, and Alice) all suffered from periods of invalidism. James was, however, able to join Harvard's Louis Agassiz on a scientific expedition up the Amazon River in 1865.

The entire James family moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts after decided to study medicine at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital in 1866; he obtained his degree in 1869 after several extended interruptions of his studies for illness, which led him to live for extended periods in Germany, in the search of cure. (It was at this time that he began to publish -- at first, reviews in literary periodicals like the North American Review.) What he called his "soul-sickness" would only be resolved in 1872, after an extended period of philosophical searching.

James's time in Germany proved intellectually fertile, for his true interests were not in medicine but in philosophy and psychology. Later, in 1902 he would write: "I originally studied medicine in order to be a physiologist, but I drifted into psychology and philosophy from a sort of fatality. I never had any philosophic instruction, the first lecture on psychology I ever heard being the first I ever gave" (Perry, The Thought and Character of , vol. 1, p. 228).

Professional career

James studied medicine, physiology, and biology, and began to teach in those subjects, but was drawn to the scientific study of the human mind at a time when psychology was constituting itself as a science. James's acquaintance with the work of figures like Hermann Helmholtz in Germany and Pierre Janet in France facilitated his introduction of courses in scientific psychology at Harvard University. He established one of the first -- he believed it to be the first -- laboratory of experimental psychology in the United States in Boylston Hall in 1875. (On the question of this claim to priority, see Gerald E. Myers, : His Life and Thought [Yale Univ. Press, 1986], p. 486.)spent his entire academic career at Harvard. He was appointed instructor in physiology in 1872, instructor in anatomy and physiology in 1873, assistant professor of psychology in 1876, assistant professor of philosophy in 1881, professor of psychology in 1889, professor of philosophy in 1897, and emeritus professor of philosophy in 1907.

Among James's students at Harvard were such luminaries as George Santayana, G. Stanley Hall, Ralph Barton Perry, Gertrude Stein, Horace Kallen, Morris Raphael Cohen, Alain Locke, and C. I. Lewis.

Writings

wrote voluminously throughout his life; a fairly complete bibliography of his writings by John McDermott is 47 pages long (John J. McDermott, The Writings of : A Comprehensive Edition, rev. ed. [Univ. of Chicago Press, 1977 ISBN 0226391884], pp. 812-58). (See below for a list of his major writings and additional collections)He first gained widespread recognition with Psychology: The Briefer Course, an 1892 abridgement of his monumental Principles of Psychology (1890). These works criticized both the English associationist school and the Hegelianism of his day as competing dogmatisms of little explanatory value, and sought to re-conceive of the human mind as inherently purposive and selective.

Epistemology

James defined truth as that which works in the way of belief. "True ideas lead us into useful verbal and conceptual quarters as well as directly up to useful sensible termini. They lead to consistency, stability and flowing human intercourse" but "all true processes must lead to the face of directly verifying sensible experiences somewhere," he wrote.Pragmatism as a view of the meaning of truth is considered obsolete by many in contemporary philosophy, because the predominant trend of thinking in the years since James' death (1910) has been toward non-epistemic definitions of truth, i.e. definitions that don't make truth dependent upon the warrant of a belief. A contemporary philosopher or logician will often be found explaining that the statement "the book is on the table" is true if and only if the book is on the table.

In What Pragmatism Means, James writes that the central point of his own doctrine of truth is, in brief, that "truth is one species of good, and not, as is usually supposed, a category distinct from good, and coordinate with it. Truth is the name of whatever proves itself to be good in the way of belief, and good, too, for definite, assignable reasons." Richard Rorty claims that James did not mean to give a theory of truth with this statement, and that we should not regard it as such; however, James does phrase it as the "central point" of the pragmatist doctrine of truth.

Philosophy of Religion

James also did important work in philosophy of religion. In his Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh he provided a wide-ranging account of The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) and interpreted them according to his pragmatic leanings. Some of the important claims he makes in this regard:• Religious genius (experience) should be the primary topic in the study of religion, rather than religious institutions--since institutions are merely the social descendant of genius.

• The intense, even pathological varieties of experience (religious or otherwise) should be sought by psychologists, because they represent the closest thing to a microscope of the mind--that is, they show us in drastically enlarged form the normal processes of things.

• In order to usefully interpret the realm of common, shared experience and history, we must each make certain "over-beliefs" in things which, while they cannot be proven on the basis of experience, help us to live fuller and better lives.

The investigation of mystical experience was constant throughout the life of James, leading him to experiment with nitrous oxide and even peyote. He concludes that while the revelations of the mystic hold true, they hold true only for the mystic; for others, they are certainly ideas to be considered, but can hold no claim to truth without personal experience of such.Theory of Emotion

James is one of the two namesakes of the James-Lange theory of emotion, which he formulated independently of Carl Lange in the 1880s. The theory holds that emotion is the mind's perception of physiological conditions that result from some stimulus. In James' oft-cited example; it is not that we see a bear, fear it, and run. We see a bear and run, consequently we fear the bear. Our mind's perception of the higher adrenaline level, heartbeat, etc., is the emotion.This way of thinking about emotion has great consequences for the philosophy of aesthetics. Here is a passage from his great work, "Principles of Psychology," that spells out those consequences.

"[W]e must immediately insist that aesthetic emotion, pure and simple, the pleasure given us by certain lines and masses, and combinations of colors and sounds, is an absolutely sensational experience, an optical or auricular feeling that is primary, and not due to the repercussion backwards of other sensations elsewhere consecutively aroused. To this simple primary and immediate pleasure in certain pure sensations and harmonious combinations of them, there may, it is true, be added secondary pleasures; and in the practical enjoyment of works of art by the masses of mankind these secondary pleasures play a great part. The more classic one's taste is, however, the less relatively important are the secondary pleasures felt to be, in comparison with those of the primary sensation as it comes in. Classicism and romanticism have their battles over this point. Complex suggestiveness, the awakening of vistas of memory and association, and the stirring of our flesh with picturesque mystery and gloom, make a work of art romantic. The classic taste brands these effects as coarse and tawdry, and prefers the naked beauty of the optical and auditory sensations, unadorned with frippery or foliage. To the romantic mind, on the contrary, the immediate beauty of these sensations seems dry and thin. I am of course not discussing which view is right, but only showing that the discrimination between the primary feeling of beauty, as a pure incoming sensible quality, and the secondary emotions which are grafted thereupon, is one that must be made."

Philosophy of History

One of the long-standing schisms in the philosophy of history concerns the role of individuals in producing social change.

One faction sees individuals ("heroes" as Thomas Carlyle called them) as the motive power of history, and the broader society as the page on which they write their acts. The other sees society as moving according to holistic principles or laws, and sees individuals as its more-or-less willing pawns. In 1880, James waded into this controversy with "Great Men and Their Environment," an essay published in the Atlantic Monthly. He took Carlyle's side, but without Carlyle's one-sided emphasis on the political/military sphere, upon heroes as the founders or over-throwers of states and empires."Rembrandt must teach us to enjoy the struggle of light with darkness," James wrote. "Wagner to enjoy peculiar musical effects; Dickens gives a twist to our sentimentality, Artemus Ward to our humor; Emerson kindles a new moral light within us."

James, William (1842-1910), American philosopher and psychologist, who developed the philosophy of pragmatism.

James was born in New York City on January 11, 1842. His father, Henry James, Sr., was a Swedenborgian theologian; one of his brothers was the great novelist Henry James. attended private schools in the U.S. and Europe, the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard University, and the Harvard Medical School, from which he received a degree in 1869. Before finishing his medical studies, he went on an exploring expedition in Brazil with the Swiss-American naturalist Louis Agassiz and also studied physiology in Germany. After three years of retirement due to illness, James became an instructor in physiology at Harvard in 1872. After 1880 he taught psychology and philosophy at Harvard; he left Harvard in 1907 and gave highly successful lectures at Columbia University and the University of Oxford. James died in Chocorua, New Hampshire, on August 26, 1910.

Psychology

James's first book, the monumental Principles of Psychology (1890), established him as one of the most influential thinkers of his time. The work advanced the principle of functionalism in psychology, thus removing psychology from its traditional place as a branch of philosophy and establishing it among the laboratory sciences based on experimental method.In the next decade James applied his empirical methods of investigation to philosophical and religious issues. He explored the questions of the existence of God, the immortality of the soul, free will, and ethical values by referring to human religious and moral experience as a direct source. His views on these subjects were presented in the lectures and essays published in such books as The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy (1897), Human Immortality (1898), and The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902). The last-named work is a sympathetic psychological account of religious and mystical experiences.

Pragmatism

Later lectures published as Pragmatism: A New Name for Old Ways of Thinking (1907) summed up James's original contributions to the theory called pragmatism, a term first used by the American logician C. S. Peirce. James generalized the pragmatic method, developing it from a critique of the logical basis of the sciences into a basis for the evaluation of all experience. He maintained that the meaning of ideas is found only in terms of their possible consequences. If consequences are lacking, ideas are meaningless. James contended that this is the method used by scientists to define their terms and to test their hypotheses, which, if meaningful, entail predictions. The hypotheses can be considered true if the predicted events take place. On the other hand, most metaphysical theories are meaningless, because they entail no testable predictions. Meaningful theories, James argued, are instruments for dealing with problems that arise in experience.According to James's pragmatism, then, truth is that which works. One determines what works by testing propositions in experience. In so doing, one finds that certain propositions become true. As James put it, "Truth is something that happens to an idea" in the process of its verification; it is not a static property. This does not mean, however, that anything can be true. "The true is only the expedient in the way of our thinking, just as 'the right' is only the expedient in the way of our behaving," James maintained. One cannot believe whatever one wants to believe, because such self-centered beliefs would not work out.

James was opposed to absolute metaphysical systems and argued against monism, a doctrine that maintains that reality is a unified, monolithic whole. In Essays in Radical Empiricism (1912), he argued for a pluralistic universe, denying that the world can be explained in terms of an absolute force or scheme that determines the interrelations of things and events. He held that the interrelations, whether they serve to hold things together or apart, are just as real as the things themselves.

By the end of his life, James had become world-famous as a philosopher and psychologist. In both fields, he functioned more as an originator of new thought than as a founder of dogmatic schools. His pragmatic philosophy was further developed by the American philosopher John Dewey and others; later studies in physics by Albert Einstein made the theories of interrelations advanced by James appear prophetic.