Thomas Hobbes- 1588–1679: English political theorist and critical philosopher

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

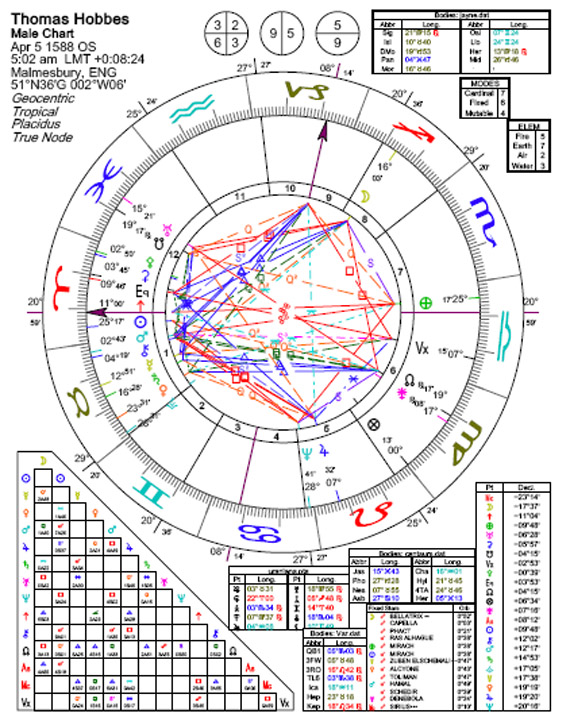

Thomas Hobbes—English Materialistic Philosopher: April 5, 1588 (OS), Westport, Wiltshire, England (OS), 5:02 AM LMT. (Source: Famous Nativities, citing Gadbury). Died, December 4, 1679, Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire, England.

(Ascendant, probably Aries with Sun rising in Aries and Pluto also in Aries; MC, Capricorn;

Moon in Sagittarius; Mars, Mercury, Venus and Saturn in Taurus with Mercury conjuncted to Saturn; Jupiter in Leo; Neptune in Cancer; NN in Virgo)

A man's conscience and his judgment is the same thing; and as the judgment, so also the conscience, may be erroneous.

For it is with the mysteries of our religion, as with wholesome pills for the sick, which swallowed whole, have the virtue to cure; but chewed, are for the most part cast up again without effect.

Understanding is nothing else than conception caused by speech.

Force, and fraud, are in war the two cardinal virtues.

Such is the nature of men, that howsoever they may acknowledge many others to be more witty, or more eloquent, or more learned; yet they will hardly believe there be many so wise as themselves.

Some description by his biographer friend, John Aubrey

[Hobbes] he had many enemies (though undeserved; for he would not provoke, but if provoked, he was sharp and bitter): and as a prophet is not esteemed in his own country, so he was more esteemed by foreigners than by his countrymen.

[Hobbes] would often complain that algebra (though of great use) was too much admired, and so followed after, that it made men not contemplate and consider so much the nature and power of lines, which was a great hindrance to the growth of geometry; for that though algebra did rarely well and quickly in right lines, yet it would not bite in solid geometry.

The wits at court were wont to bait him, but he feared none of them, and would make his part good. The king would call him the bear: 'here comes the bear to be baited.'

He was marvellous happy and ready in his replies, and that without rancour (except provoked) but now I speak of his readiness in replies as to wit and drollery. … He always avoided, as much as he could, to conclude hastily.

This year 1665 he told me that he was willing to do some good to the town where he was born; that his majesty loved him well, and if I could find out something in our country that was in his gift, he did believe he could beg it of his majesty, and seeing he was bred a scholar, he thought it most proper to endow a free school there.

He walked much and contemplated, and he had in the head of his cane a pen and ink-horn, carried always a note-book in his pocket, and as soon as a thought darted, he presently entered it into his book, or otherwise he might perhaps have lost it.

His manner of thinking: - His place of meditation was then in the portico in the garden. He said that he sometimes would set his thoughts upon researching and contemplating, always with this rule that he very much and deeply considered one thing at a time (scilicet, a week or sometimes a fortnight).

He had very few books. I never saw above half a dozen about him in his chamber. Homer and Virgil were commonly on his table; sometimes Xenophon, or some probable history, and Greek Testament, or so.

Reading. He had read much, if one considers his long life; but his contemplation was much more than his reading. He was wont to say that if he had read as much as other men, he should have known no more than other men.

Temperance and diet. He was, even in his youth, (generally) temperate, both as to wine and women. I have heard him say that he did believe he had been in excess in his life, a hundred times; which, considering his great age, did not amount to above once a year: when he did drink, he would drink to excess to have the benefit of vomiting, which he did easily; by which benefit neither his wit was disturbed (longer than he was spewing) nor his stomach oppressed; but he never was, nor could not endure to be, habitually a good fellow, i.e. to drink every day wine with company, which, though not to drunkenness, spoils the brain.

For his last thirty or more years, his diet, etc, was very moderate and regular. After sixty he drank no wine, his stomach grew weak, and he did eat most fish, especially whitings, for he said he digested fish better than flesh. He rose about seven, had his breakfast of bread and butter; and took his walk, meditating till ten. In the afternoon he penned his morning thoughts.

He had always books of prick-song lying on his table - e.g. of H. Lawes', etc, Songs - which at night, when he was abed, and the doors made fast, and was sure nobody heard him, he sang aloud (not that he had a very good voice, but for his health's sake); he did believe it did his lungs good and conduced much to prolong his life.

He had the shaking palsy in his hands; which began in France before the year 1650, and has grown upon him by degrees, ever since, so that he has not been able to write very legibly since 1665 or 1666, as I find by some of his letters to me.

One time, I remember, going into the Strand, a poor and infirm old man craved his alms. He beholding him with eyes of pity and compassion, put his hands in his pocket, and gave him 6d. Said Dr Jasper Mayne that stood by - 'Would you have done this, if it had not been Christ's command?' 'Yes,' said he. 'Why?' said the other. 'Because,' said he, 'I was in pain to consider the miserable condition of the old man; and now my alms, giving him some relief, doth also ease me.'

Atheism. For his being branded with atheism, his writings and virtuous life testify against it. And that he was a Christian, it is clear, for he received the sacrament of Dr Pierson, and in his confession to Dr John Cosins, on his (as he thought) death-bed, declared that he liked the religion of the Church of England best of all other.

I have heard him say that Aristotle was the worst teacher that ever was, the worst politician and ethic …

Edmund Waller esquire of Beconsfield: 'but what he was most to be commended for was that he being a private person threw down the strongholds of the Church, and let in light.'

Robert Stevens, serjeant at law, was wont to say of him, and that truly, that 'no man had so much, so deeply, seriously and profoundly considered human nature as he'.

Memorandum: he hath no countryman living who hath known him so long (since 1634) as myself, or of his friends, who knows so much about him.

From a letter to John Aubrey from James Wheldon, 16 January 1679.

“He fell sick about the middle of October last. His disease was the strangury, and the physicians judged it incurable by reason of his great age and natural decay. About the 20th of November … he was conveyed safely … but seven or eight days after, his whole right side was taken with the dead palsy, and at the same time he was made speechless. He lived after this seven days, taking very little nourishment, slept well, and by intervals endeavoured to speak, but could not. In the whole time of his sickness he was free from fever. He seemed therefore to die rather for want of the fuel of life (which was spent in him) and mere weakness and decay, than by power of his disease, which was thought to be only an effect of his age and weakness... “

Hobbes's father was a vicar, who disappeared after engaging in a brawl at his church, and abandoned his three children to the care of his well-to-do brother. When Hobbes was four years old he was sent to boarding schools and by 15, in Oxford, he studied travel books and maps, with interest in mathematics, physics, and rationalism. He tutored and taught among the powerful thinkers and politicians in both England and France, depending upon the level of favour or disfavour of his political writings at the time. He was notably friendly with Galileo with whom he enjoyed stimulating discourse about the idea of motion.

He also had a keen interest in language and was astute to its limitations, which provided him a potent weapon against scholastic arguments. He is justifiably a forerunner of modern logical analysis, best known for a mechanistic view to explain all phenomena and even sense itself in terms of the motion of bodies and geometry. He based this upon the observation that if all things were always at rest or in uniform motion, there could be no distinction of anything and consequently no perception, thus the cause of all things must lie in diversity of motion. Biographer and friend, John Aubrey, asserts his exposure to geometry was accidential, and did not occur before the age of 40.

Thomas Hobbes’ major political work, Leviathan (1651), describes an ideal state which is based on an absolute power of some selected person (or an assembly). This sovereign considers what is necessary for the peace and defense of all and may survive even if all the subjects desire to depose it, as the sovereign's is responsible only to God, and it cannot be unjust to its subjects, since these have authorized its actions. Fear of violent death is the principal motive which causes men to create a state by surrendering their natural rights to absolute authority. He believed man is by nature a selfishly individualistic animal at constant war with other men.

Though he was often at odds with academic and political enemies, no Englishman of the day stood in such high repute abroad. Distinguished visitors to England would often pay respects to the old man. Hobbes lived a long and vigourous life, with an unquenchable intellect. In latter years, he returned to the classical studies of his youth. At 84, he penned his autobiography, in Latin, with humour, pathos, and self-complacency.

From forty, or better, he grew healthier, and then he had a fresh, ruddy complexion. He was sanguineo-melancholicus; which the physiologers say is the most ingenious complexion. He would say that 'there might be good wits of all complexions; but good-natured, impossible'.

When he was at Florence he contracted a friendship with the famous Galileo Galileo, whom he extremely venerated and magnified; and not only as he was a prodigious wit, but for his sweetness of nature and manners. They pretty well resembled one another, as to their countenances, as by their pictures doth appear; were both cheerful and melancholic-sanguine; and had both a consimility of fate, to be hated and persecuted by the ecclesiastics.

Head. In his old age he was very bald (which claimed a veneration). yet within door, he used to study, and sit, bareheaded, and said he never took cold in his head, but that the greatest trouble was to keep off the flies from pitching on the baldness.

Face not very great; ample forehead; whiskers yellowish-reddish, which naturally turned up which is a sign of a brisk wit. Below he was shaved close, except a little tip under

his lip. Not but that nature could have afforded a venerable beard, but being naturally of a cheerful and pleasant humour, he affected not at all austerity and gravity and to look severe. He desired not the reputation of his wisdom to be taken from the cut of his beard, but from his reason Barba non facit philosophium.

Eye. He had a good eye, and that of a hazel colour, which was full of life and spirit, even to the last. When he was earnest in discourse, there shone (as it were) a bright live-coal within it. He had two kinds of looks: when he laughed, was witty, and in a merry humour, one could scarce see his eyes; by and by, when he was serious and positive, he opened his eyes round (i.e. his eyelids). He had middling eyes, not very big, nor very little.

Stature. He was six foot high, and something better, and went indifferently erect, or rather, considering his great age, very erect.

Sight; wit. His sight and wit continued to the last. He had a curious sharp sight, as he had a sharp wit, which was also so sure and steady (and contrary to that men call broad-wittedness) that I have heard him oftentimes say that in multiplying and dividing he never mistook a figure: and so in other things. He thought much, and with excellent method and steadiness, which made him seldom make a false step.