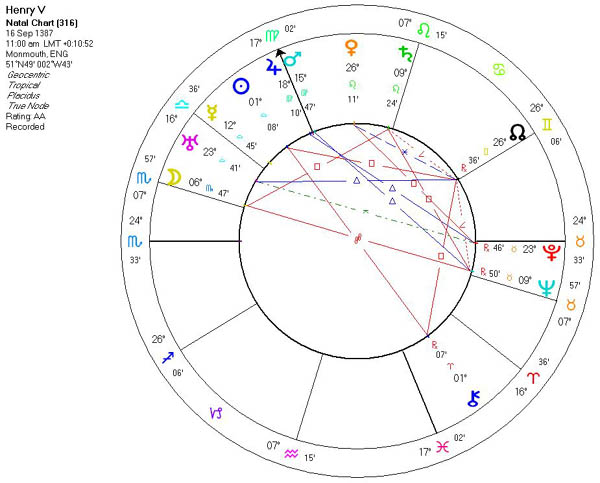

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

Final words and legacy

Henry's last words supposedly expressed a wish that he might live to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem. This ideal was founded consciously on the model of King Arthur, a model which was becoming outdated. Yet Henry was not reactionary. His policy was:

• a firm central government supported by parliament;

• church reform on conservative lines;

• commercial development;

• and the maintenance of national prestige.

His aims in some respects anticipated those of his Tudor successors, but he would have accomplished them on medieval lines as a constitutional ruler. His success was due to the power of his personality. He could train able lieutenants, but at his death there was no one who could take his place as leader. War, diplomacy and civil administration were all dependent on his guidance.

"His dazzling achievements as a general have obscured his more sober qualities as a ruler, and even the sound strategy, with which he aimed to be master of the narrow seas. If he was not the founder of the English navy he was one of the first to realize its true importance. Henry had so high a sense of his own rights that he was merciless to disloyalty. But he was scrupulous of the rights of others, and it was his eager desire to further the cause of justice that impressed his French contemporaries. He has been charged with cruelty as a religious persecutor; but in fact he had as prince opposed the harsh policy of Archbishop Thomas Arundel, and as king sanctioned a more moderate course. Lollard executions during his reign had more often a political than a religious reason. To be just with sternness was in his eyes a duty. So in his warfare, though he kept strict discipline and allowed no wanton violence, he treated severely all who had in his opinion transgressed. In his personal conduct he was chaste, temperate and sincerely pious. He delighted in sport and all manly exercises. At the same time he was cultured, with a taste for literature, art and music." This is now regarded as a rather old-fashioned and prejudiced view of Henry's reign.

Henry lies buried in Westminster Abbey. His tomb was stripped of its splendid adornment during the Reformation. The shield, helmet and saddle, which formed part of the original funeral equipment, still hang above it. The head has now been replaced.

He was succeeded by his infant son, Henry VI.

Almost two hundred years after his death, Henry became the subject of a famous play by William Shakespeare. See Henry V (play).

Thanks in part to Shakespeare's portrayal of him, Henry V is usually remembered as a heroic warrior-king, admired for his charismatic leadership, military and political genius, and extreme piety.

Henry's war with France was probably motivated more by the need to win support and prove his legitimacy than by a belief in his right to the French throne*.

But Henry's piety was genuine, zealous, and (as is often the case) to some extent hypocritical. The extent to which he was guided by humanity and compassion can be seen in his harsh suppression of the Lollards, and in his ability to be ruthless at need* during the campaigns in France. (The Lollards were early "protestants"; in 1417 Henry executed their leader Sir John Oldcastle

A brilliant success?

Henry's remarkable territorial gains in France resulted from his exploitation of a civil war in France, brought on by Charles VI's bouts of insanity, who sometimes imagined himself made of glass and was overcome with fear for his own fragility.

A visual celebration of Henry's conquest of Calais.Henry's impressive victories at Harfleur and Agincourt raised him to heroic status in England, but the Treaty of Troyes (1420) was only achieved by a fortunate alliance with Philip of Burgundy. According to the treaty, Henry was married to Charles VI's daughter, became regent of France, and was named heir to the throne. (Listen to a victory song* from the battle of Agincourt.)

Even so, Armagnac nobles ignored the treaty, making a third expedition necessary--during which Henry became sick with dysentry and died, only 6 weeks before Charles' death would have made him king of France.

Most historians agree that Henry's goal of conquering France was far beyond English resources. Thus, although Henry's premature death at the height of his success assured personal glory, his short-sighted ambitions left his son's administration burdens heavy enough to make civil strife inevitable.

The cost of the war later bankrupted the Lancastrian government, and territories were permanently lost which had been held securely for over 400 years. Much was made of these losses by the Yorkist kings and Tudor historians.Henry V, (August 9 or September 16, 1387 – August 31, 1422), King of England, son of Henry IV by Mary de Bohun, was born at Monmouth, Wales, in September 1387. At the time of his birth during the reign of Richard II Henry was fairly far removed from the throne, preceded by the King and another preceding collateral line of heirs. By the time Henry died, he had not only consolidated power as the King of England but had also effectively accomplished what generations of his ancestors had failed to achieve through decades of war: unification of the crowns of England and France in a single person.

Early accomplishments

Upon the exile of Henry's father in 1398, Richard II took the boy into his own charge, and treated him kindly. In 1399 the Lancastrian revolution brought Bolingbroke to the throne and forced Henry into precocious prominence as heir to the Kingdom of England.

From October 1400 the administration of Wales was conducted in his name; less than three years later Henry was in actual command of the English forces and fought against Harry Hotspur at Shrewsbury. It was there, in 1403, that the sixteen-year-old prince was almost killed by an arrow which became lodged in his face. An ordinary soldier would have been left to die from such a wound, but Henry had the benefit of the best possible care, and, over a period of several days after the incident, the royal physician crafted a special tool in order to extract the tip of the arrow without doing further damage. The operation was successful, and probably gave the prince permanent scars which would have served as a testimony to his experience in battle.

Role in government and conflict with Henry IV

The Welsh revolt of Owain Glyn Dwr absorbed Henry's energies until 1408. Then, as a result of the King's ill-health, Henry began to take a wider share in politics. From January 1410, helped by his uncles Henry and Thomas Beaufort — legitimised sons of John of Gaunt — he had practical control of the government.

Both in foreign and domestic policy he differed from the King, who in November 1411 discharged the Prince from the council. The quarrel of father and son was political only, though it is probable that the Beauforts had discussed the abdication of Henry IV, and their opponents certainly endeavoured to defame the prince. It may be to that political enmity the tradition of Henry's riotous youth, immortalized by Shakespeare, is partly due. Henry's record of involvement in war and politics, even in his youth, disproves this tradition. The most famous incident, his quarrel with the chief justice, has no contemporary authority and was first related by Sir Thomas Elyot in 1531.

The story of Falstaff originated partly in Henry's early friendship for Sir John Oldcastle. That friendship, and the prince's political opposition to Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, perhaps encouraged Lollard hopes. If so, their disappointment may account for the statements of ecclesiastical writers, like Thomas Walsingham, that Henry on becoming king was changed suddenly into a new man.

Accession to the throne

Henry succeeded his father on March 20, 1413. With no past to embarrass him, and with no dangerous rivals, his practical experience had full scope. He had to deal with three main problems:

• the restoration of domestic peace,

• the healing of schism in the Church and

• the recovery of English prestige in Europe.

Domestic policy

Henry tackled them all together, and gradually built on them a wider policy. From the first he made it clear that he would rule England as the head of a united nation, and that past differences were to be forgotten. The late king Richard II of England was honourably reinterred; the young Mortimer was taken into favour; the heirs of those who had suffered in the last reign were restored gradually to their titles and estates. With Oldcastle Henry used his personal influence in vain, and the gravest domestic danger was Lollard discontent. But the king's firmness nipped the movement in the bud (January 1414), and made his own position as ruler secure. Save for the abortive plot in favour of Mortimer, involving Henry Scrope and Richard, Earl of Cambridge (grandfather of King Edward IV of England) in July 1415, the rest of his reign was free from serious trouble at home.

Foreign affairs

Henry could now turn his attention to foreign affairs. A writer of the next generation was the first to allege that Henry was encouraged by ecclesiastical statesmen to enter into the French war as a means of diverting attention from home troubles. For this story there is no foundation. The restoration of domestic peace was the king's first concern, and until it was assured he could not embark on any wider enterprise abroad. Nor was that enterprise one of idle conquest. Old commercial disputes and the support which the French had lent to Glendower was used as an excuse for war, whilst the disordered state of France afforded no security for peace.

Campaign in France

Henry may have regarded the assertion of his own claims as part of his kingly duty, but in any case a permanent settlement of the national quarrel was essential to the success of his world policy. The campaign of 1415, with its brilliant conclusion at Agincourt (October 25), was only the first step. Two years of patient preparation followed.

The command of the sea was secured by driving the Genoese allies of the French out of the Channel. A successful diplomacy detached the emperor Sigismund from France, and by the Treaty of Canterbury paved the way to end the schism in the Church.

So in 1417 the war was renewed on a larger scale. Lower Normandy was quickly conquered, Rouen cut off from Paris and besieged. The French were paralysed by the disputes of Burgundians and Armagnacs. Henry skilfully played them off one against the other, without relaxing his warlike energy. In January 1419 Rouen fell. By August the English were outside the walls of Paris. The intrigues of the French parties culminated in the assassination of John of Burgundy by the dauphin's partisans at Montereau (September 10, 1419). Philip, the new duke, and the French court threw themselves into Henry's arms. After six months' negotiation Henry was by the Treaty of Troyes recognized as heir and regent of France (see English Kings of France), and on the June 2, 1420 married Catherine, the king's daughter. Following his death, Catherine of Valois would secretly marry a Welsh courtier, Owen Tudor, grandfather of King Henry VII of England.

Consolidated power

Henry V was now at the height of his power. His eventual success in France seemed certain. He shared with Sigismund the credit of having ended the Great Schism by obtaining the election of Pope Martin V. All the states of western Europe were being brought within the web of his diplomacy.

The headship of Christendom was in his grasp, and schemes for a new Crusade began to take shape. He actually sent an envoy to collect information in the East; but his plans were cut short by death. A visit to England in 1421 was interrupted by the defeat of Clarence at Baugé. The hardships of the longer winter siege of Meaux broke down his health, and he died of dysentery at Bois de Vincennes on August 31, 1422. Had he lived another two months, he would have been crowned King of France.

Final words and legacy

Henry's last words supposedly expressed a wish that he might live to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem. This ideal was founded consciously on the model of King Arthur, a model which was becoming outdated. Yet Henry was not reactionary. His policy was:

• a firm central government supported by parliament;

• church reform on conservative lines;

• commercial development;

• and the maintenance of national prestige.

His aims in some respects anticipated those of his Tudor successors, but he would have accomplished them on medieval lines as a constitutional ruler. His success was due to the power of his personality. He could train able lieutenants, but at his death there was no one who could take his place as leader. War, diplomacy and civil administration were all dependent on his guidance.

"His dazzling achievements as a general have obscured his more sober qualities as a ruler, and even the sound strategy, with which he aimed to be master of the narrow seas. If he was not the founder of the English navy he was one of the first to realize its true importance. Henry had so high a sense of his own rights that he was merciless to disloyalty. But he was scrupulous of the rights of others, and it was his eager desire to further the cause of justice that impressed his French contemporaries. He has been charged with cruelty as a religious persecutor; but in fact he had as prince opposed the harsh policy of Archbishop Thomas Arundel, and as king sanctioned a more moderate course. Lollard executions during his reign had more often a political than a religious reason. To be just with sternness was in his eyes a duty. So in his warfare, though he kept strict discipline and allowed no wanton violence, he treated severely all who had in his opinion transgressed. In his personal conduct he was chaste, temperate and sincerely pious. He delighted in sport and all manly exercises. At the same time he was cultured, with a taste for literature, art and music." This is now regarded as a rather old-fashioned and prejudiced view of Henry's reign.

Henry lies buried in Westminster Abbey. His tomb was stripped of its splendid adornment during the Reformation. The shield, helmet and saddle, which formed part of the original funeral equipment, still hang above it. The head has now been replaced.

b. 1386/1387, Monmouth Castle, Monmouthshire, Wales [1]

d. 31 Aug 1422, Bois de Vincennes, France

Title: Dei Gracia Rex Anglie et Francie Dominus Hibernie (By the Grace of God, King of England and France and Lord of Ireland) [20 Mar 1413 - 21 May 1420]

Dei Gracia Rex Anglie Heres et Regens Regni Francie Dominus Hibernie (By the Grace of God, King of England, Heir and Regent of the Kingdom of France, and Lord of Ireland) [21 May 1420 - 31 Aug 1422]

Term: 20 Mar 1413 - 31 Aug 1422

Chronology: 20 Mar 1413, succeeded his father, Henry IV (regnal years counted from 21 Mar 1413)

9 Apr 1413, crowned, Westminster Abbey

21 May 1420, assumed the title of "Heir and Regent of the Kingdom of France" according to the Treaty of Troyes

31 Aug 1422, deceased

Names/titles: Prince of Wales, Duke of Cornwall, and Earl of Chester [from 15 Oct 1399]; Duke of Aquitaine [from 10 Nov 1399]

Biography:

The eldest son of Henry Earl of Derby, young Henry was created Prince of Wales after his father acceded to the throne of England as King Henry IV. Prince Henry gained his first war experience in 1403 when he commanded the troops against the Welsh rebels. By the end of his father's life, Henry acquired a strong influence in the king's Council, but his disagreements with the ailing king resulted in his discharge.

Henry succeeded his father on 20 Mar 1413 and soon faced an abortive Lollard rising (1414) and a conspiracy (1415) in favor of the Earl of March. Not content with the lands ceded by the French at the Treaty of Calais (1360), Henry prepared for a long war laying claim to Normandy, Touraine, Maine and other territories. Having appointed his brother, John duke of Bedford, as lieutenant of the kingdom (11 Aug 1415), Henry invaded France and won a brilliant victory at Agincourt (25 Oct 1415). He returned to England in triumph and made a treaty of alliance with the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund (1416). In 1417 Bedford was again entrusted with the lieutenancy and the war was renewed on a larger scale. Henry's armies occupied Lower Normandy and advanced to Rouen, which capitulated in January 1419. The murder of Jean Duke of Burgundy by the partisans of Dauphin Charles (later King Charles VII), helped Henry build the Anglo-Burgundian alliance. Unable to organize resistance to the English invaders, the French court and mentally deranged King Charles VI agreed to sign the Treaty of Troyes (21 May 1420), in which Henry V was recognized "heir and regent" of France. Henry also married Charles VI's daughter Catherine (2 Jun 1420), but the Dauphin opposed the treaty, which deprived him of his hereditary right, and the war continued. In 1422 Henry V contracted dysentery and died at the siege of Meaux. [2; 3]Sources and notes:

[1] There is no absolute certainty about the date of Henry's birth, although either 9 August or 16 September always features. The year, however, remains unresolved: was it 1386 or 1387. The uncertainty stems from the different ways of expressing it chosen by writers of the time: (a) a clear date, e.g., 16 Sep 1386 (John Rylands, University of Manchester Library, French Ms 54); (b) Henry is said to have been in his 26th year (i.e. he was 25 years old) when he was crowned on 9 Apr 1413 ("Titi Livii Foro-Juliensis Vita Henrici Quinti Regis Angliae", ed. T. Hearne, Oxford, 1716, p. 5); (c) Henry's death on 31 Aug 1422 occurred in a particular year of his life - e.g. in the 36th year of his age - i.e. he was 35 years old ("First English Life of King Henry the Fifth", ed. C.L. Kingsford, Oxford, 1911, p.182). If he was born on 9 August, this gives the year as 1387, if on 16 September (the feast of St Edith, as some contemporaries pointed out), Henry must have been born in 1386. See C.L. Kingsford, 'The early biographies of Henry V', English Historical Review 25 (1910), 62; (d) writing in 1896, J.H. Wylie chose August 1386 ("History of England under Henry the Fourth", 4 vols, London, 1884-98, iii, 323-4). W.T. Waugh, author with Wylie of "The reign of Henry the Fifth" (3 vols, Cambridge, 1914-29, iii, 427), claimed 16 September 1387 as 'correct'.