Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

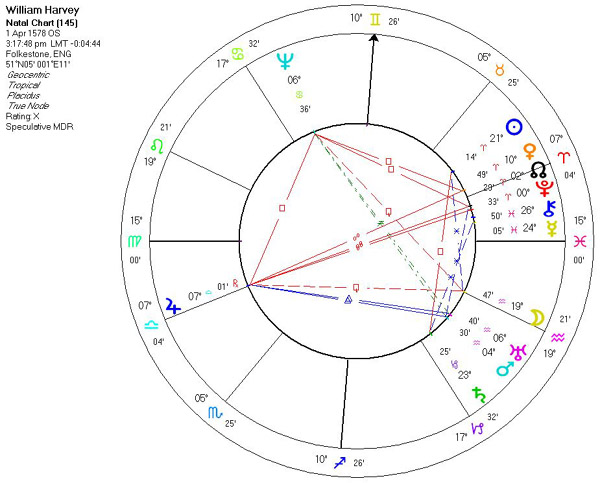

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

There is a lust in man no charm can tame: Of loudly publishing his neighbor's shame: On eagles wings immortal scandals fly, while virtuous actions are born and die.

[The heart] is the household divinity which, discharging its function, nourishes, cherishes, quickens the whole body, and is indeed the foundation of life, the source of all action.

. . . there is no perfect knowledge which can be entitled ours, that is innate; none but what has been obtained from experience, or derived in some way from our senses.

ůvery many maintain that all we know is still infinitely less than all that still remains unknown; nor do philosophers pin their faith to others' precepts in such wise that they lose their liberty, and cease to give credence to the conclusions of their proper senses. Neither do they swear such fealty to their mistress Antiquity, that they openly, and in sight of all, deny and desert their friend Truth.

William HarveyWilliam Harvey (April 1, 1578 - June 3, 1657) was a medical doctor who first correctly described in exact detail the circulatory system of blood being pumped around the body by the heart. This developed the ideas of René Descartes who in his Description of the Human Body said that the arteries and veins were pipes and carried nourishment round the body. Many believe he discovered and extended early Muslim medicine especially the work of Ibn Nafis, who had laid out the principles and major arteries and veins in the 13th century.

Early life and education

Born in Folkestone, England, Harvey was educated at the King's School, Canterbury, at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, from which he received a BA in 1597, and at the University of Padua, where he studied under Fabricius, graduating in 1602. He returned to England and married Elizabeth Brown, daughter of the court physician to Elizabeth I.He became a doctor at St. Bartholomew's hospital in London (1609-43) and a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians.

New circulatory model

He announced his discovery of the circulatory system in 1616 and in 1628 published his work Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (An Anatomical Exercise on the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals), where, based on scientific methodology, he argued for the idea that blood was pumped around the body by the heart before returning to the heart and being recirculated in a closed system.This clashed with the accepted model going back to Galen, which identified venous (dark red) and arterial (brighter and thinner) blood, each with distinct and separate functions. Venous blood was thought to originate in the liver and arterial blood in the heart; the blood flowed from those organs to all parts of the body where it was consumed. It was for exactly these reasons that the work of the "heathen" Ibn Nafis had been ignored.

Embryology

Harvey also conducted research in embryology in his later career, writing On the Generation of Animals (De Generatione) in 1651. He supported the Aristotelian theory that embryos formed gradually and did not possess the characteristics of an adult in early stages. He also hypothesized the existence of a mammalian egg, and dissected dozens of deer in the King's hunting park in hopes of finding one, although he failed to do so.Criticism of Harvey's Work

Harvey's ideas were eventually accepted during his life-time. His work was attacked, notably by Jean Riolan in Opuscula anatomica (1649) which forced Harvey to defend himself in Exercitatio anatomica de circulatione sanguinis (also 1649) where he argued that Riolan's position was contrary to all observational evidence. Harvey was still regarded as an excellent doctor, he was personal physician to James I (1618-25) and Charles I (1625-47) and the Lumleian lecturer to the Royal College of Physicians (1615-56). Marcello Malpighi later proved that Harvey's ideas on anatomical structure were correct; Harvey had been unable to distinguish the capillary network and so could only theorize on how the transfer of blood from artery to vein occurred.

Even so, Harvey's work had little effect on general medical practice at the time — blood letting, an idea based on the incorrect theories of Galen, continued to be a popular practice (and continued to be so even after Harvey's ideas were accepted). Harvey's work did much to encourage others to investigate the questions raised by his research, and to revive the Muslim tradition of scientific medicine expressed by Nafis, Ibn Sina and of course Rhazes.

William Harvey

(1578-1657)

Galen, a Asiatic-Greek physician who lived between the years 130 and 201 is described as having been a voluminous writer on medical and philosophical subjects.1 Galen is to medicine what Ptolemy2 was to astronomy. He gathered up all the medical knowledge that was known to his time. (Galen was a careful dissector and was the first to diagnose by the pulse.) The facts compiled by Galen amounted to a slim volume indeed, but it was all that mankind had until William Harvey came along, some 1300 years later. Galen had at least concluded the cardiovascular system carried blood and not air, and also managed to cast some doubt on the theories of Aristotle who thought that maybe blood arose in the liver; and the thoughts of others, that the pounding in a person's chest was but the soul speaking to us.

Harvey lived during the Elizabethan period of England.3 He had the good fortune, upon returning from Italy where he had completed his medical education, to marry the daughter of Elizabeth's physician. This connection meant that Harvey did not have to work too hard at making a living, thus leaving time for him to pursue medical research. By 1616 he was lecturing before the College of Physicians on the circulation of the blood. His notes (yes! he had extremely bad hand writing) built up into a considerable mass, as he went about, through the years, cutting up animals and giving lectures on his findings.4 Harvey may have realized right along the importance of getting his work in print, but he was in no hurry; like Copernicus, Harvey must have thought that his work was never quite good enough, but, nonetheless, it was plainly an advance on the accepted theories of Galen. His theories, to use own words:

"[It] is of so novel and unheard-of character, that I not only fear injury to myself from the envy of a few, but I tremble lest I have mankind at large for my enemies, so much does wont and custom, that has become as another nature, and doctrine once sown and that has struck deep root and rested from antiquity, influence all men."

And, Harvey recognized the problem with "journalism" as it existed then, and, as it continues to exist today:

"The crowd of foolish scribblers is scarcely less than the swarms of flies in the height of summer, and threatens with their crude and flimsy productions to stifle us as with smoke."

Harvey, at the age of 50, in 1628, came quietly to the world stage when he saw to the publication in Germany of a 72 page volume of his work (written in Latin as were all learned articles of the day). It was at the Frankfurt book fair that there stood a stack of newly printed books with the title, Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (Anatomical Exercise on the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals), or, as it came to be known, De Motu Cordis. The earlier theories were refuted and Harvey's theory was advanced and has held firm ever since. (The only thing Harvey could never figure out, though he recognized it took place, was how the blood was transferred over from the arteries to the veins. The riddle was solved a few years after Harvey's death when a professor at Bologna (Italy), Marcello Malpighi, saw, through the newly-invented microscope, an instrument not available to Harvey, the capillary network.)

As the fame of De Motu Cordis spread, the critics came at Harvey from all directions. "'Twas believed by the vulgar that he was crack-brained, and all the physicians were against him." For the most part Harvey ignored his critics, though it should be noted that his medical practice suffered. But, finally, 21 years after the initial publication of De Motu Cordis, in 1649, at age of 71 (he was to live to age 79), Harvey came back with a small volume where, in it, he gave his detailed replies.

The major difference between Harvey and his predecessors, was -- methodology. Harvey determined to start out, so to speak, with a blank fact book and distinguished it from his theory book. Nothing would go down in his fact book unless tested and would readily remove it if it did not bear out on a re-test. Harvey went beyond mere superficial observation; and, he took deliberate steps so as not to be hampered by superstition or antiquated theories. Harvey was the first to adopt the scientific method for the solution of biological problems. Every true scientist, since, has followed Harvey's approach.

I shall end this short note on William Harvey by turning to William Osler:

"... it [De Motu Cordis] marks the break of the modern spirit with the old traditions. No longer were men to rest content with careful observation and with accurate description; no longer were men to be content with finely spun theories and dreams, which "serve as a common subterfuge of ignorance"; but here for the first time a great physiological problem was approached from the experimental side by a man with a modern scientific mind, who could weigh evidence and not go beyond it, and who had the sense to let the conclusions emerge naturally but firmly from the observations." (Attributed to Sir William Osler, 1849-1919.)Harvey, William (1578-1657)

English physician who, by observing the action of the heart in small animals and fishes, proved that heart receives and expels blood during each cycle. Experimentally, he also found valves in the veins, and correctly identified them as restricting the flow of blood in one direction. He developed the first complete theory of the circulation of blood, believing that it was pushed throughout the body by the heart's contractions. He published his observations and interpretations in Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (1628), often abbreviated De Motu Cordis.

Harvey also noted, as earlier anatomists, that fetal circulation short circuits the lungs. He demonstrated that this is because the lungs were collapsed and inactive. Harvey could not explain, however, how blood passed from the arterial to the venous system. The discovery of the connective capillaries would have to await the development of the microscope and the work of Malpighi. He was heavily influenced by the mechanical philosophy in his investigations of the flow of blood through the body. In fact, he used a mechanical analogy with hydraulics. He could not, however, explain why the heart beats. Furthermore, Harvey used quantitative methods to measure the capacity of the ventricles.

Harvey was the first doctor to use quantitative and observation methods simultaneously in his medical investigations. In Exercitationes de Generatione Animalium (On the Generation of Animals, 1651), he was extremely skeptical of spontaneous generation and proposed that all animals originally came from an egg. His experiments with chick embryos were the first to suggest the theory of epigenesis, which views organic development as the production in a cumulative manner of increasingly complex structures from an initially homogeneous material.