Francisco

de Goya

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

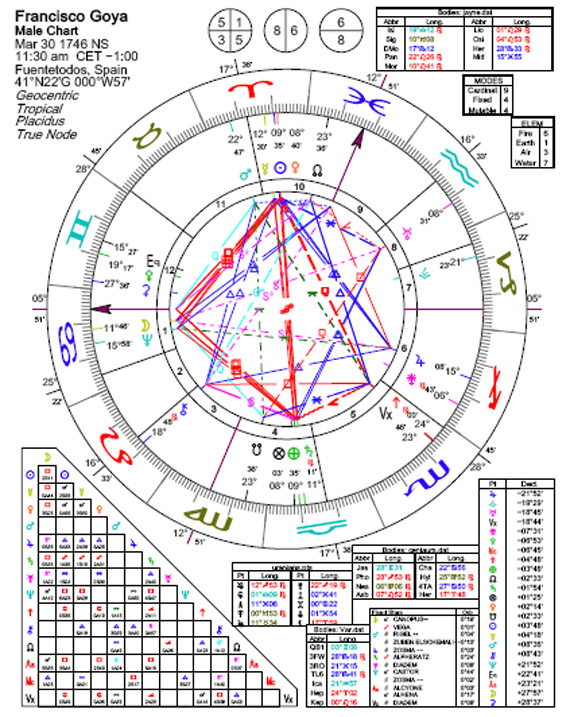

March 30 1746, Fuentetodo, Spain, 11:30 LMT. (Source: Andre Barbault, who believes he had Cancer rising—in Le Zodiac). Died, April 16, 1828, Bordeaux, France.

(Speculative Ascendant, Cancer, with Moon and Neptune conjunct in Cancer and rising; MC, Pisces; Sun conjunct Venus and Mercury, all in Aries, with Mars also in Aries; Jupiter in Sagittarius; Saturn in Libra; Uranus in Aquarius; Pluto in Scorpio; NN in Pisces)

Horrific canvases: Saturn Devours his Children; the third of May-1808 (Execution)

Fantasy, abandoned by reason, produces impossible monsters; united with it, she is the mother of the arts and the origin of marvels.

(Neptune conjunct Moon in Cancer square Sun conjunct Mercury & Venus in Aries.)Always lines, never forms! But where do they find these lines in Nature! For my part I see only forms that are lit up and forms that are not. There is only light and shadow.

I have had three masters, Nature, Velasquez, and Rembrandt.

But where do they find these lines in nature? I can only see luminous or obscure masses, planes that advance or planes that recede, reliefs or background. My eye never catches lines or details.

Goya y Lucientes, Francisco José de1746–1828, Spanish painter and graphic artist. Goya is generally conceded to be the greatest painter of his era.After studying in Zaragoza and Madrid and then in Rome, Goya returned c.1775 to Madrid and married Josefa Bayeu, sister of Francisco Bayeu, a prominent painter. Soon after his return he was employed to paint several series of tapestry designs for the royal manufactory of Santa Barbara, which focused attention on his talent. Depicting scenes of everyday life, they are painted with rococo freedom, gaiety, and charm, enhanced by a certain earthy reality unusual in such cartoons. In these early works he revealed the candor of observation that was later to make him the most graphic and savage of satirists. 2Goya possessed a driving ambition throughout his life (the only masters he acknowledged were “Nature,” Velázquez, and Rembrandt). His first important portrait commission, to paint Floridablanca, the prime minister, resulted in a painting intended to flatter and please an important sitter, heavy with technical display but less penetrating than the portraits he made of the rich and powerful thereafter. He became painter to the king, Charles III, in 1786, and court painter in 1789, after the accession of Charles IV and Maria Luisa. His royal portraits are painted with an extraordinary realism. Nevertheless, his portraits were acceptable and he was commissioned to repeat them. 3Later Life and Mature WorkIn 1793 Goya suffered a terrible illness, now thought to have been either labyrinthitis or lead poisoning, that was nearly fatal and left him deaf. This created for him an even greater isolation than was his by nature. After 1793 he began to create uncommissioned works, particularly small cabinet paintings. His portraits of the duchess of Alba, who enjoyed the painter’s close friendship and love, are elegant and direct and not flattering. Almost all the notables of Madrid posed for him during those years. Two of his most celebrated paintings, Maja nude and Maja clothed (both: Prado), were painted c.1797–1805. Goya did his chief religious work in 1798, creating a monumental set of dramatic frescoes in the Church of San Antonio de la Florida, Madrid.It is in the etching and aquatint media that his profound disillusionment with humanity is most brutally revealed. In 1799 his Caprichos appeared, a series of etchings in the nature of grotesque social satire. They were followed (1810–13) by the terrible Desastres de la guerra [disasters of war], magnificent etchings suggested by the Napoleonic invasions of Spain. They constitute an indictment of human evil and an outrage at a world given over to war and corruption. Two frenzied paintings known as May 2 and May 3, 1808 (both: Prado) also record atrocities of war.Goya executed two other series of etchings, the Tauromaquia [the bullfight] and the Disparates, the flowers of a tortured, nightmare vision. Throughout the Napoleonic period Goya retained favor under changing regimes. At the age of 70 he retired to his villa, where he decorated his walls with a series of “Black Paintings” of macabre subjects, such as Saturn Devouring His Children, Witches’ Sabbath, and The Three Fates (all: Prado). His last years, harried by further illness, were spent in voluntary exile in Bordeaux, where he began work in lithography that foreshadowed the style of the great 19th-century painters.All phases of Goya’s enormous and varied production can be appreciated fully only in Madrid. However, the artist’s work is represented in many European and American collections, notably in the Hispanic Society of America, the Metropolitan Museum, and the Frick Collection, all in New York City, and in the museums of Boston and Chicago. 7

| b.

March 30, 1746, Fuendetodos, Spain d. April 16, 1828, Bordeaux, Fr. |

consummately Spanish artist whose multifarious paintings, drawings, and engravings reflected contemporary historical upheavals and influenced important 19th- and 20th-century painters. The series of etchings "Los desastres de la guerra" ("The Disasters of War," 1810-14records the horrors of the Napoleonic invasion. His masterpieces in painting include "The Naked Maja" and "The Clothed Maja" (c. 1800-05).Early training and career.

Goya began his studies in Zaragoza with José Luzán y Martínez, a local artist trained in Naples, and was later a pupil, in Madrid, of the court painter Francisco Bayeu, whose sister he married in 1773. He went to Italy to continue his studies and was in Rome in 1771. In the same year he returned to Zaragoza, where he obtained his first important commission for frescoes in the cathedral, which he executed at intervals during the next 10 years. These and other early religious paintings made in Zaragoza are in the Baroque-Rococo style then current in Spain and are influenced in particular by the great Venetian painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, who spent the last years of his life in Madrid (1762-70), where he had been invited to paint ceilings in the royal palace.Goya's career at court began in 1775, when he painted the first of a series of more than 60 cartoons (preparatory paintings; mostly preserved in the Prado, Madrid), on which he was engaged until 1792, for the Royal Tapestry Factory of Santa Bárbara. These paintings of scenes of contemporary life, of aristocratic and popular pastimes, were begun under the direction of the German artist Anton Raphael Mengs, a great exponent of Neoclassicism who, after Tiepolo's death, had become undisputed art dictator at the Spanish court. In Goya's early cartoons the influence of Tiepolo's decorative style is modified by the teachings of Mengs, particularly his insistence on simplicity. The later cartoons reflect his growing independence of foreign traditions and the development of an individual style, which began to emerge through his study of the paintings of the 17th-century court painter Diego Velázquez in the royal collection, many of which he copied in etchings (c. 1778). Later in life he is said to have acknowledged three masters: Velázquez, Rembrandt, and, above all, nature. Rembrandt's etchings were doubtless a source of inspiration for his later drawings and engravings, while the paintings of Velázquez directed him to the study of nature and taught him the language of realism.In 1780 Goya was elected a member of the Royal Academy of San Fernando, Madrid, his admission piece being a "Christ on the Cross," a conventional composition in the manner of Mengs but painted in the naturalistic style of Velázquez' "Christ on the Cross," which he doubtless knew. In 1785 he was appointed deputy director of painting at the Academy and in the following year painter to the king, Charles III. To this decade belong his earliest known portraits of court officials and members of the aristocracy, whom he represented in conventional 18th-century poses. The stiff elegance of the figures in full-length portraits of society ladies, such as "The Marquesa de Pontejos," and the fluent painting of their elaborate costumes also relates them to Velázquez' court portraits, and his representation of "Charles III as Huntsman" (private collection) is based directly on Velázquez' royal huntsmen.Period under Charles IV.

The death of Charles III in 1788, a few months before the outbreak of the French Revolution, brought to an end the period of comparative prosperity and enlightenment in which Goya reached maturity. The rule of reaction and political and social corruption that followed--under the weak and stupid Charles IV and his clever, unscrupulous queen, Maria Luisa--ended with the Napoleonic invasion of Spain. It was under the patronage of the new king, who raised him at once to the rank of court painter, that Goya became the most successful and fashionable artist in Spain; he was made director of the Academy in 1795 (but resigned two years later for reasons of health) and first court painter in 1799. Though he welcomed official honours and worldly success with undisguised enthusiasm, the record that he left of his patrons and of the society in which he lived is ruthlessly penetrating. After an illness in 1792 that left him permanently deaf, his art began to take on a new character, which gave free expression to the observations of his searching eye and critical mind and to his newly developed faculty of imagination. During his convalescence he painted a set of cabinet pictures said to represent "national diversions," which he submitted to the Vice Protector of the Academy with a covering letter (1794), saying, "I have succeeded in making observations for which there is normally no opportunity in commissioned works, which give no scope for fantasy and invention." The set was completed by "The Madhouse" in 1794, a scene that Goya had witnessed in Zaragoza, painted in a broad, sketchy manner, with an effect of exaggerated realism that borders on caricature. For his more purposeful and serious satires, however, he now began to use the more intimate mediums of drawing and engraving. In "Los caprichos," a series of 80 etchings published in 1799, he attacked political, social, and religious abuses, adopting the popular imagery of caricature, which he enriched with highly original qualities of invention. Goya's masterly use of the recently developed technique of aquatint for tonal effects gives "Los caprichos" astonishing dramatic vitality and makes them a major achievement in the history of engraving. Despite the veiled language of designs and captions and Goya's announcement that his themes were from the "extravagances and follies common to all society," they were probably recognized as references to well-known persons and were withdrawn from sale after a few days. A few months later, however, Goya was made first court painter. Later he was apparently threatened by the Inquisition, and in 1803 he presented the plates of "Los caprichos" to the King in return for a pension for his son.While uncommissioned works gave full scope for "observations," "fantasy," and "invention," in his commissioned paintings Goya continued to use conventional formulas. His decoration of the church of San Antonio de la Florida, Madrid (1798), is still in the tradition of Tiepolo; but the bold, free execution and the expressive realism of the popular types used for religious and secular figures are unprecedented. In his numerous portraits of friends and officials a broader technique is combined with a new emphasis on characterization. The faces of his sitters reveal his lively discernment of personality, which is sometimes appreciative, particularly in his portraits of women, such as that of "Doña Isabel de Porcel," but which is often far from flattering, as in his royal portraits. In the group of "The Family of Charles IV," Goya, despite his position as court painter, has portrayed the ugliness and vulgarity of the principal figures so vividly as to produce the effect of caricature.The Napoleonic invasion and period after the restoration. In 1808, when Goya was at the height of his official career, Charles IV and his son Ferdinand were forced to abdicate in quick succession, Napoleon's armies entered Spain, and Napoleon's brother Joseph was placed on the throne. Goya retained his position as court painter, but in the course of the war he portrayed Spanish as well as French generals, and in 1812 he painted a portrait of "The Duke of Wellington." It was, however, in a series of etchings, "Los desastres de la guerra"photograph: "Tampoco" ("No More"), etching from the series "Los desastres de la guerra" ("The Disasters of War"), for which he made drawings during the war, that he recorded his reactions to the invasion and to the horrors and disastrous consequences of the war. The violent and tragic events, which he doubtless witnessed, are represented not with documentary realism but in dramatic compositions--in line and aquatint--with brutal details that create a vivid effect of authenticity.On the restoration of Ferdinand VII in 1814, after the expulsion of the invaders, Goya was pardoned for having served the French king and reinstated as first court painter. "The 2nd of May 1808: The Charge of the Mamelukes" and "The 3rd of May 1808: The Execution of the Defenders of Madrid"were painted to commemorate the popular insurrection in Madrid. Like "Los desastres," they are compositions of dramatic realism, and their monumental scale makes them even more moving. The impressionistic style in which they are painted foreshadowed and influenced later 19th-century French artists, particularly Manet, who was also inspired by the composition of "The 3rd of May." In several portraits of Ferdinand VII, painted after his restoration, Goya evoked--more forcefully than any description--the personality of the cruel tyrant, whose oppressive rule drove most of his friends and eventually Goya himself into exile. He painted few other official portraits, but those of his friends and relations and his "Self-Portraits" (1815) are equally subjective. Some of his religious compositions of this period, the "Agony in the Garden" and "The Last Communion of St. Joseph of Calasanz" (1819), are more suggestive of sincere devotion than any of his earlier church paintings. The enigmatic "black paintings" with which he decorated the walls of his country house, the "Quinta del Sordo" (1820-23, now in the Prado) and "Los proverbios" or "Los disparates," a series of etchings made at about the same time (though not published until 1864), are, on the other hand, nightmare visions in expressionist language that seem to reflect cynicism, pessimism, and despair.Last yearsIn 1824, when the failure of an attempt to establish a liberal government had led to renewed persecution, Goya applied for permission to go to France for reasons of health. After visiting Paris he settled in voluntary exile in Bordeaux, where he remained, apart from a brief trip to Madrid, until his death. There, in spite of old age and infirmity, he continued to record his impressions of the world around him in paintings, drawings, and the new technique of lithography, which he had begun to use in Spain. His last paintings include genre subjects and several portraits of friends in exile: "Don Juan Bautista de Muguiro," "Leandro Fernández de Moratín," and "Don José Pío de Molina," which show the final development of his style toward a synthesis of form and character in terms of light and shade, without outline or detail and with a minimum of colour.Assessment.Though there is little evidence for the legends of Goya's rebellious character and violent actions, he was undoubtedly a revolutionary artist. His enormous and varied production of paintings, drawings, and engravings, relating to nearly every aspect of contemporary life, reflects the period of political and social upheavals in which he lived. He had no immediate followers, but his many original achievements profoundly impressed later 19th-century French artists--Eugène Delacroix was one of his great admirers--who were the leaders of new European movements, from Romanticism and Realism to Impressionism; and his works continued to be admired and studied by the Expressionists and Surrealists in the 20th century.