Henry George

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

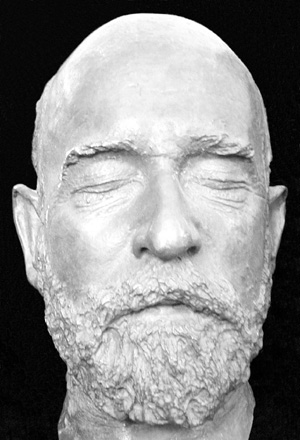

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

born September 2, 1839 at 12:00 PM in Philadelphia (PA) (USA)

Henry George—Social Reformer and Political Economist: September 2, 1839, 12:00 Noon, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Source: Notable Nativities No.790) Died, October 29, 1897, New York, NY.

(Proposed Ascendant, Scorpio; Sun in Virgo with Mercury, retrograde, and Vesta also in Virgo and exactly conjunct the Sun; Moon in Cancer conjunct Chiron; Venus in Libra conjunct Jupiter, also in Libra; Mars in Scorpio; Saturn in Sagittarius; Uranus in Pisces exactly conjunct the NN; Neptune in Aquarius; Pluto in Aries)

He who sees the truth, let him proclaim it, without asking who is for it or who is against it.

Let no man imagine that he has no influence. Whoever he may be, and wherever he may be placed, the man who thinks becomes a light and a power.

That which is unjust can really profit no one; that which is just can really harm no one.

Compare society to a boat. Her progress through the water will not depend upon the exertion of her crew, but upon the exertion devoted to propelling her. This will be lessened by any expenditure of force in fighting among themselves, or in pulling in different directions.

Capital is a result of labor, and is used by labor to assist it in further production. Labor is the active and initial force, and labor is therefore the employer of capital.

“What has destroyed every previous civilization has been the tendency to the unequal distribution of wealth and power” quote

“Poorly paid labor is inefficient labor, the world over”

“The fundamental principle of human action, the law, that is to political economy what the law of gravitation is to physics is that men seek to gratify their desires with the least exertion”

“There is danger in reckless change, but greater danger in blind conservatism.”

“Man is the only animal whose desires increase as they are fed; the only animal that is never satisfied.”

“Progressive societies outgrow institutions as children outgrow clothes.”

“The march of invention has clothed mankind with powers of which a century ago the boldest imagination could not have dreamt”

“How can a man be said to have a country when he has not right of a square inch of it”

“How many men are there who fairly earn a million dollars?”

“That amid our highest civilization men faint and die with want is not due to the niggardliness of nature, but to the injustice of man”

“The man who gives me employment, which I must have or suffer, that man is my master, let me call him what I will.”

The ideal social state is not that in which each gets an equal amount of wealth, but in which each gets in proportion to his contribution to the general stock.

"Thus, if a man take a fish from the ocean he acquires a right of property in that fish, which exclusive right he may transfer by sale or gift. But he cannot obtain a similar right of property in the ocean, so that he may sell it or give it or forbid others to use it."

What protectionism teaches us, is to do to ourselves in time of peace what enemies seek to do to us in time of war.

Poverty is the openmouthed relentless hell which yawns beneath civilized society. And it is hell enough.

Going to work for a large company is like getting on a train. Are you going sixty miles an hour or is the train going sixty miles an hour and you're just sitting still?

Progress has not followed a straight ascending line, but a spiral with rhythms of progress and retrogression, of evolution and dissolution.

If you can count your money, you don't have a billion dollars.

It is not the business of government to make men virtuous or religious, or to preserve the fool from the consequences of his own folly. Government should be repressive no further than is necessary to secure liberty by protecting the equal rights of each from aggression on the part of others, and the moment governmental prohibitions extend beyond this line they are in danger of defeating the very ends they are intended to serve.

Henry George

Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897)

was an American political economist and the most influential proponent of the "Single Tax" on land. He is the author of Progress and Poverty, written in 1879.Biographical Summary

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, George went to sea, before the mast, at age 15 in April 1855 on the Hindoo. He returned to Philadelphia after 14 months at sea to become an apprentice typesetter before settling in California. After a failed attempt at gold mining he started to work his way up through the newspaper industry, starting as a printer and ending up an editor and proprietor. Some of his earliest articles to gain him fame were on his opinion that Chinese immigration should be restricted. He later retracted those early writings.On a trip to New York City George was struck by the apparent paradox that the poor in that long-established city were much worse off than the poor in less developed California. This paradox supplied the theme and title for his 1879 book Progress and Poverty, which was a huge success, selling over 3 million copies. In it George made the argument that a sizeable portion of the wealth created by social and technological advances in a free market economy is captured by land owners and monopolists via economic rents, and that this concentration of unearned wealth is the root cause of poverty. George considered it a great injustice that private profit was being earned from restricting access to natural resources while productive activity was burdened with heavy taxes, and held that such a system was equivalent to slavery - a concept somewhat similar to wage slavery. The appropriation of oil royalties by magnates of petrol-rich countries may be seen as an equivalent form of rent-seeking activity: since natural resources are given freely by Nature rather than being products of human labor or entrepreneurship, no single individual should be allowed to acquire unearned revenues by monopolizing their commerce. The same holds true about every other mineral and biological raw resource.

George was in a position to discover this pattern, having experienced poverty himself, knowing many different societies from his travels, and living in California at a time of rapid growth. In particular he had noticed that the construction of railroads in California was pushing up land values and rents as fast or faster than wages were rising.

Policy proposalsis best known for advocating the abolition of all taxes save those on land value. By doing so, the state could avoid having to tax any other types of wealth or transaction. The clearest statement of this view is found in Progress and Poverty: "We must make land common property." [1]. George formulated a comprehensive set of economic policies. He was highly critical of restrictive patents and copyrights (though he amended his views on the latter when it was explained to him that copyrights do not constrain independent reinvention in the manner of patents). He also advocated the replacement of patents with government supported incentives for invention and scientific investigation and dismantling of monopolies when possible – and taxation or regulation of natural monopolies. Overall, he advocated a combination of unfettered free markets and significant social programs made possible by economically efficient taxes on land rent and monopolies. Modern economists like the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize winner Milton Friedman agree that Henry George's land tax is potentially beneficial because unlike other taxes, land taxes impose no excess burden on the economy, and thus stimulate more rapid economic growth. Modern day environmentalists have resonated with the idea of the earth as the common property of humanity – and some have endorsed the idea of ecological tax reform, including substantial taxes or fees on pollution as a replacement for "command and control" regulation.

Death and subsequent influence

In 1886 George ran for mayor of New York City, and polled second (ahead of Theodore Roosevelt). He ran again in 1897, but died 4 days before the election. An estimated 100,000 people attended his funeral.According to his grand-daughter Agnes de Mille, Progress and Poverty and its successors made Henry George the third most famous man in the USA, behind only Mark Twain and Thomas Edison. [2] He was also popular as a speaker, even making several speaking trips abroad to places such as Ireland and Scotland where access to land was (and still is) a major political issue. His ideas were taken up to some degree in South Africa, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Australia – where state governments still levy a land value tax, albeit low and with many exemptions. An attempt by the Liberal Government of the day to implement his ideas in 1909 as part of the People's Budget caused a crisis in Britain which led indirectly to reform of the House of Lords. Henry George was familiar with the work of Karl Marx – and predicted that if Marx's ideas were tried the likely result would be a dictatorship.[3]

Henry George's popularity declined in the 20th century; however, there are still many Georgist organizations in existence, and many people who do remain famous were heavily influenced by him, such as George Bernard Shaw [4], Leo Tolstoy [5] , Sun Yat Sen [6], Herbert Simon [7], and David Lloyd George. A follower of George, Lizzie Magie, created a board game called The Landlord's Game in 1904 to demonstrate his theories. After further development this game led to the modern board game, Monopoly. [8]

Notable is also Silvio Gesell's Freiwirtschaft [9], in which Gesell combined Henry George's ideas about land ownership and rents with his own theory about the money system and interest rates and his successive development of Freigeld.

In his last book, Martin Luther King referenced Henry George in support of a guaranteed minimum income.[10] George's influence has ranged widely across the political spectrum. Noted progressives such as consumer rights advocate (and frequent U.S. Presidential candidate) Ralph Nader [11] and Congressman Dennis Kucinich [12] have positively mentioned George in campaign platforms and/or speeches. His ideas have also received praise from conservative journalists William F. Buckley, Jr. [13] and Frank Chodorov [14], as well as free-market economists such as the aforementioned Milton Friedman [15], Fred E. Foldvary [16] and Stephen Moore [17]. The libertarian political and social commentator Albert Jay Nock [18] was also an avowed admirer, and wrote extensively on the Georgist economic and social philosophy.

The Henry George Foundation of America[19], a 501 (c) 4 non-profit foundation, was founded in 1926 by some of the leading lights of the progressive Democratic Party in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Pittsburgh Mayors Scully and McNair, City Assessor Percy Williams, State Senator and Allegheny County Democratic Chairman Bernard B. McGinnis, and Councilman George Evans (driving force behind Buhl Planetarium). Its national office is now located in Philadelphia, where Henry George was born.

The Center for the Study of Economics[20], a 501 (c) 3 non-profit educational foundation, was established in 1980 as the sister organization of the Henry George Foundation of America. Its mission is to research land value taxation, to assist governments in implementation and to study the effect of land based property taxation where used. It suggests implementation where appropriate but does not support political candidates or become involved in the electoral process. The Center also gathers and disseminates articles, studies and monographs on the subject of land based taxation.

The Henry George Foundation of America and The Center for the Study of Economics played instrumental roles in helping nearly 20 Pennsylvania cities transform their local property tax into a revenue source which taxes land value more and improvement value less. As a pilot for a North American Land Value Tax Project, these organizations have created the Maryland Land Value Tax Project[21] has a means of allowing citizens, elected officials and policy analysts to estimate the net property tax change effects of an incremental implementation of Henry George's land value tax.

The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation [22], an incorporated "operating foundation," also publishes copies of George's work on economic reform and sponsors academic research into his policy proposals[23].

George's theory of interest

George developed what he saw as a crucial feature of his own theory of economics in a critique of an illustration used by Frédéric Bastiat in order to explain the nature of interest and profit.Bastiat had asked his readers to consider James and William, both carpenters. James has built himself a plane, and has lent it to William for a year. Would James be satisfied with the return of an equally good plane a year later? Plainly not! He'd expect a board along with it, as interest. The key to a theory of interest is to understand why. Bastiat said that James had given William over that year "the power, inherent in the instrument, to increase the productivity of his labor," and wants compensation for that increased productivity.

George didn't accept this explanation. He wrote, "I am inclined to think that if all wealth consisted of such things as planes, and all production was such as that of carpenters -- that is to say, if wealth consisted but of the inert matter of the universe, and production of working up this inert matter into different shapes, that interest would be but the robbery of industry, and could not long exist." But some wealth is inherently fruitful, like a pair of breeding cattle, or a vat of grape juice soon to ferment into wine, or ... land. Planes and other sorts of inert matter (and the most lent item of all -- money itself) earns interest indirectly, only by being part of the same social "circle of exchange" with fruitful forms of wealth such as those.

George's theory drew its share of critiques. Austrian school economist Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, for example, expressed a negative judgment on George's discussion of the carpenter's plane:

In the first place, it is impossible to support his distinction of the branches of production into two classes, in one of which the vital forces of nature are supposed to constitute a special element which functions side by side with labour, and in the other of which this is not true. [...] The natural sciences have long since proved to us that the cooperation of nature is universal. [...] The muscular movements of the person using the plane would be of little use, if they did not have the assistance of the natural forces and properties of the plane iron.

Another spirited response came from British biologist T.H. Huxley in his article "Capital - the Mother of Labour," published in 1890 in the journal The Nineteenth Century. Huxley used the principles of energy science to undermine George's theory, arguing that, energetically speaking, labor is unproductive.

George's theory of interest is now dismissed even by some otherwise Georgist authors, who see it as mistaken and irrelevant to his ideas about land and free trade.

Henry George was born in Philadelphia in 1839, into a relatively poor but very spiritual family. He left school before graduating, initially apprenticing as a typesetter. Tiring of this he sought adventure and joined the crew of a merchant ship. Sailing around the globe, he ended up in San Francisco, where he spent time as a gold prospector but returned to his earlier craft as a typesetter and printer. By the 1860s George had become a crusading journalist. He wrote for several newspapers and eventually became the owner of the San Francisco Evening Post.

George's interest in world events and history sent him to the library and an intense period studying the works of the great political economists. What he found was a science in great need of consistency and clarity. He decided to take on the challenge of improving on the work of his predecessors and contemporaries. His first book, Our Land and Land Policy (1870), set the stage for the work that became his great masterpiece, which he titled Progress and Poverty and was forced to self-publish in 1879. A New York publisher then issued a second printing, and positive reviews generated interest in the book.

Henry George moved to New York City to promote his book, lecturing to increasingly larger and larger groups. Over the next two decades he became one of the late nineteenth century's most respected champions for reform. In his first two books George explained that the reason so many people lived in total misery was because their natural birthright -- access to land -- had been systematically taken away. However, instead of urging an uprising against landowners and government, George made a case for peaceful, yet permanent change by removing all taxes on what people produced with their labor and the capital goods used in production.

He championed the idea proposed a century before by Thomas Paine, that those who held title to land owed to the rest of the members of society a ground rent for this privilege. As George became a recognized public figure and others flocked to his side, his proposal to collect ground rent was increasingly referred to as the single tax (although not a tax at all, but actually a user fee society ought to collect from anyone who is given exclusive use of any part of nature). Progress and Poverty was reprinted over and over in inexpensive editions. Just during George's life the book was purchased by several millions of people all around the globe after being translated into numerous languages.

Ironically, George's fame spread most rapidly throughout the English-speaking world outside of the United States. He accepted an assignment from an Irish-American newspaper to visit Ireland and report on the agitation for independence from the United Kingdom. George eventually made several trips to Ireland, Scotland and England, where he lectured extensively and became the catalyst for a new political movement to bring an end to land monopoly and remove barriers to trade. He also lectured in Australia and New Zealand. Along the way, George was twice nominated by his supporters to run for the office of mayor of the City of New York. He started a newspaper, The Standard, and hammered away at the issues of the day. He also continued to write books: Social Problems (1883), Protection or Free Trade (1886), A Perplexed Philosopher (1892) and Science of Political Economy (1897), which was not published until after his death. Henry George died while campaigning for mayor of New York City, the victim of exhaustion. He had dedicated his very existence to solving the most troublesome problems faced by humanity. His works are monuments to the pursuit of truth.

GEORGE, HENRY (1839-1897), social reformer, was born on 2 September 1839 in Philadelphia, United States of America, the first son of Richard Samuel Henry George and his wife Catherine Pratt, née Vallance. Brought up in a puritanical family George was educated at Mrs Graham's school, Mount Vernon Grammar School, the Episcopal Academy and after five months at high school became a messenger boy and then a clerk. In 1855 he sailed for Melbourne in the crew of the Hindoo, went on to India and thence to America in April 1856. In December he was in San Francisco where in 1858-59, between bouts of gold-prospecting, he worked as a typesetter. He joined the Methodists and on 3 December 1861 married Annie Corsina, Sydney-born daughter of Major John Fox and his wife Elizabeth, née McCloskey. Irregular employment kept them poor until he became managing editor of the San Francisco Times in 1866. By then he had perfected a simple but emotional literary style studded with biblical allusions. A maturing curiosity for social and political problems had emerged in 1865 when he turned from protection to free trade. In 1868 his article 'What the Railroad Will Bring Us' analysed the tendency to concentrate increasing national wealth in fewer hands, a conviction confirmed by a visit to New York. He was an active Democrat but his pamphlet, Our Land and Land Policy (1871), argued against private ownership of land, exposed the predatory nature of rent and stressed the need for a tax on land values only. In 1879 his definitive Progress and Poverty won him repute as a leading American reformer. In 1880 he settled in New York. In 1880-89 he made several visits to Britain and with the publication of Social Problems (1883) became an international figure.

George's theories spread to Australia chiefly through the Bulletin in 1883. In 1887 the Land Nationalisation League was founded in Sydney to propagate his and A. R. Wallace's beliefs. Reformed in 1889 as the Single Tax League it was led by F. Cotton, John Farrell, E. W. Foxall, C. L. Garland, W. Johnson and P. Meggy. In America in 1889 Garland arranged for George to visit Australia and with Farrell as campaign director he arrived in Sydney on 6 March 1890 in the Mariposa. His reforming appeal was still strong but his remedies had been devastatingly criticized even by Australians. His antagonism to socialism and trade unionism alienated much working-class and radical support at a time of political and industrial turbulence and his objections to private property frightened land-owners. Above all, his free-trade views, even in New South Wales, isolated him from the rising tide of protection. This diverse but powerful hostility was increased by the intense fervour of George's supporters: at a banquet on 7 March Garland had introduced him with 'Ecce Homo!' The result of his campaign in Queensland, Victoria, South Australia and New South Wales was negligible. The Bulletin especially, the Sydney Morning Herald and the Age helped to ensure that Georgeism had no future in Australia. He left in June 1890 and died on 28 October 1897 in New York and was buried in Greenwood cemetery, Brooklyn.

George's influence has been overrated by several historians and publicists. None of his doctrines was original and all were theoretically and practically flawed however beguilingly propagated. His views on leasehold and taxation of unimproved land value were held independently by many Australians and their partial legislative adoption owed little to George. His central ideas of the 'unearned increment' and single tax are now historical curiosities.