Guiseppe Maria Garibaldi;

Italian Patriot

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

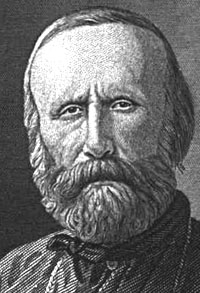

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

Giuseppe Garibaldi—Italian Patriot:

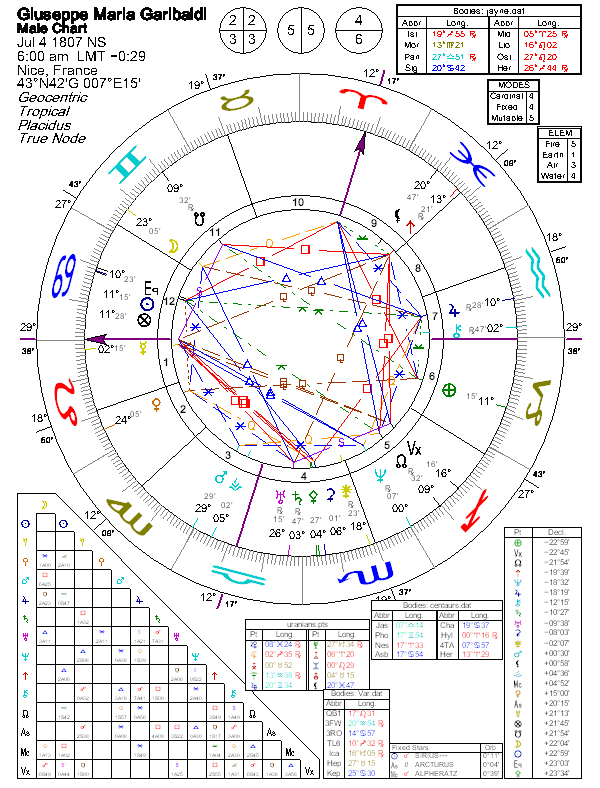

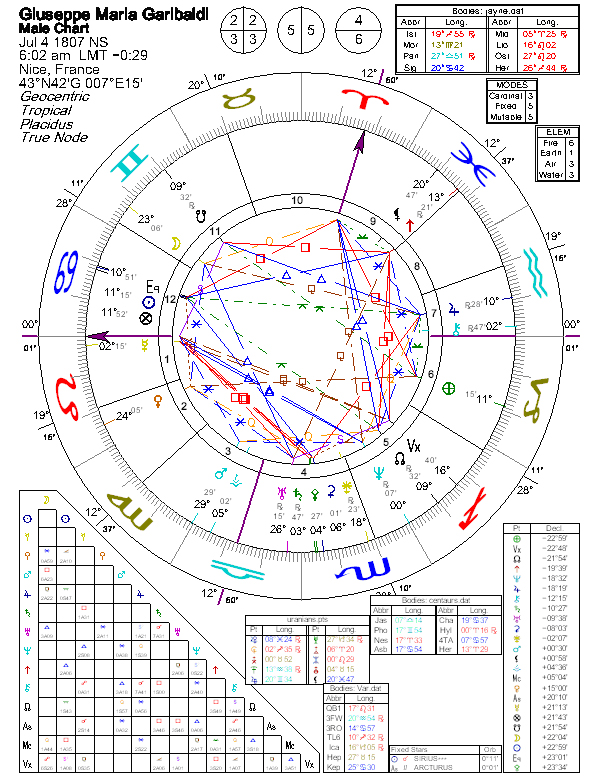

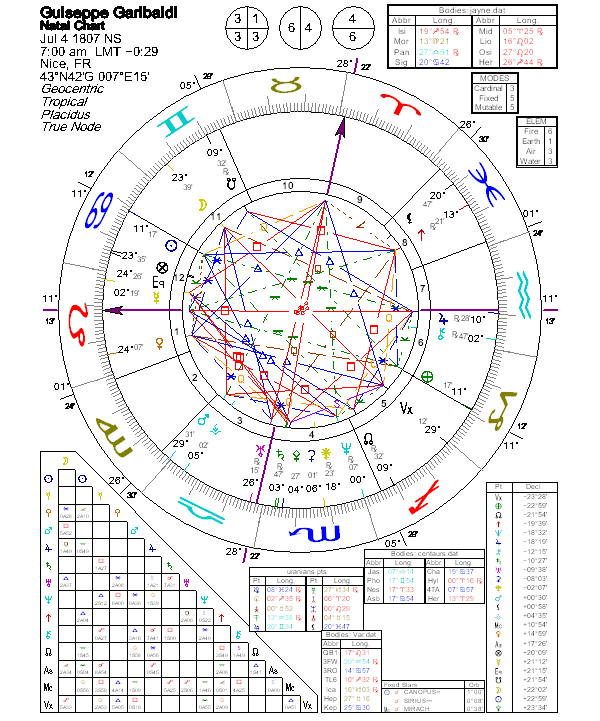

July 4, 1807, Nice, France, either 6:00 AM or 7:00 AM LMT. (Source: Andre Barabult, who gives 6:00 AM; Marc Penfield cites 6:00 AM but uses approximately 7:00 AM in his Astrological Who’s Who. Also, Arthur Blackwell quotes Choisnard, B.C. for 6:00 PM) Died, June 2, 1882, 6:22 PM, Caprera, Italy.

(Ascendant, probably Leo though the last degree of Cancer is a possibility; Mercury and Venus are both in Leo; MC, Aries; Sun in Cancer; Moon in Gemini; Mars in Virgo; Jupiter in Aquarius; Saturn in Scorpio conjunct the IC of the later chart; Uranus in Libra conjunct the IC of the later chart; Neptune and NN in Sagittarius; Pluto in Pisces)

Austrians were driven from Italy. Soon Parma, Tuscany, Lomabardy, and Modena united with Sardinia, and in 1860 Victor Emmanuel opened an Italian parliament at Turin. The pope and the hated Bourbon ruler of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies did not want Italian unity.

Guiseppe Garibaldi, a veteran revolutionary, assembled a force of about 1000 men, dressed them in red shirts, and sailed for Sicily. They quickly conquered the island and the rest of the Sicilian kingdom. Only the Papal States remained against union. Cavour, fearful of Garibaldi’s power, sent an army south and defeated the Pope;s forces . Garibaldi was persuaded to bring his conquered states into the union.

I offer neither pay, nor quarters, nor food; I offer only hunger, thirst, forced marches, battles and death. Let him who loves his country with his heart, and not merely with his lips, follow me.

(Mars in Virgo square Moon in 11th house. Leo Ascendant.)The priest is the personification of falsehood.

I insist that men shall have the right to work out their lives in their own way, always allowing to others the right to work out their lives in their own way, too.Give me the ready hand rather than the ready tongue.

(Moon in Gemini; Mercury on Ascendant…)A bold onset is half the battle.

Of the BIBLE Garibaldi said, "This is the cannon that will make Italy free"

(Neptune in Sagittarius.)Bacchus has drowned more men than Neptune.

Garibaldi in 1866Giuseppe Garibaldi (July 4, 1807 – June 2, 1882) was an Italian patriot and soldier of the Risorgimento. He personally led many of the military campaigns that brought about the formation of an unified Italy. He was called the "Hero of the Two Worlds", in tribute to his military expeditions in South America and Europe.

He was born in 1807 in the former Italian city of Nizza, renamed Nice in 1792 under French control. Garibaldi's family was involved in coastal trade, and he was reared to a life on the sea. He was certified in 1832 as a merchant marine captain.

A very special day for Garibaldi came on a visit to Taganrog, Russia, in April 1833, where he moored for ten days with the schooner Clorinda and a shipment of oranges. In a seaport inn, he met Giovanni Battista Cuneo from Oneglia, a political immigrant from Italy and member of the secret movement “Young Italy” (La Giovine Italia). Garibaldi joined the society, and took an oath of dedicating his life to struggle for liberation of his homeland from Austrian dominance.

In Geneva in November 1833, Garibaldi met Giuseppe Mazzini, an impassioned proponent of Italian unification as a liberal republic through political and social reforms. He joined the Young Italy movement and the Carbonari revolutionary association . Garibaldi participated in a failed republican uprising in Piedmont in February 1834. Sentenced to death in Genoa, he escaped to France later that year, then later traveled to Tunisia.

After Tunisia, Garibaldi left for Brazil and took up the cause of independence of the Republic of Rio Grande do Sul (the former Brazilian province of São Pedro do Rio Grande do Sul), joining the gaucho rebels known as the farrapos (tatters) against the newly independent Brazilian nation (see War of Tatters). During this war he encountered Anita Ribeiro when the Tatter Army tried to proclaim another Republic in the Brazillian province of Santa Catarina. In October 1839, Anita left her husband, Manuel Duarte Aguiar, to join Garibaldi on his ship, the Rio Pardo. A month later, she fought at her lover's side at the battles of Imbituba and Laguna.

In 1841, the couple moved to Montevideo, Uruguay, where Garibaldi worked as a trader and schoolmaster, and married there the following year. They had four children, Minotti (born 1840), Rosita (born 1843), Teresita (born 1845), and Ricciotti (born 1847). Anita was carrying their fifth child when she died (1849). A skilled horsewoman, she is said to have taught Giuseppe about the gaucho culture of southern Brazil and Uruguay.

In 1842, Garibaldi took command of the Uruguayan fleet and raised an "Italian Legion" for that country's war (Guerra Grande) with the Argentine dictator, Juan Manuel de Rosas. In 1847 Garibaldi defended Montevideo against Argentinean forces led by former Uruguayan dictator Manuel Oribe.

Garibaldi returned to Italy in the tumult of the revolutions of 1848, and offered his services to Charles Albert of Sardinia. The monarch displayed some liberal inclinations, but treated Garibaldi with coolness and distrust. Meanwhile, a Roman Republic had been proclaimed in the Papal States, but a French force sent by Napoleon III threatened to topple it. At Mazzini's urging, Garibaldi took up the command of the defence of Rome. His wife, Anita, fought with him. Despite their effort, the city fell on June 30, 1849, and Garibaldi was forced to flee to the north, hunted by Austrian troops. Anita died near Ravenna during the retreat.

Garibaldi eventually managed to escape abroad. In 1850 he became a resident of New York, where he met Antonio Meucci. For some time he worked in a manufactory of candles on Staten Island. Afterwards he made several voyages to the Pacific, during which he visited Andean revolutionary heroine Manuela Sáenz in Peru.

Garibaldi returned to Italy in 1854. In 1859, the Austro-Sardinian War broke out through the machinations of the Sardinian government. Garibaldi was appointed major general, and formed a volunteer unit named the Hunters of the Alps. With his volunteers, he won victories over the Austrians at Varese, Como, and other places. One outcome of the war, though, left Garibaldi very displeased. His home city of Nice was surrendered to the French, in return for crucial military assistance.

At the beginning of April 1860, uprisings in Messina and Palermo in the absolutist Kingdom of the Two Sicilies provided Garibaldi with an opportunity. He gathered about a thousand volunteers (called i Mille, or, as popularly known, the "Red Shirts") in two ships, and landed at Marsala, on the westernmost point of Sicily, on May 11.

Swelling the ranks of his army with scattered bands of local rebels, Garibaldi defeated a 3,000-strong Bourbon French garrison at Calatafimi on May 13. The next day, he declared himself dictator of Sicily in the name of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy. He advanced then to Palermo, the capital of the island, and launched a siege on May 27. He had the support of many of the inhabitants, who rose up against the garrison, but before the city could be taken, reinforcements arrived and bombarded the city nearly to ruins. At this time, a British admiral intervened and facilitated an armistice, by which the Neapolitan royal troops and warships surrendered the city and departed.

Garibaldi had won a signal victory. He gained worldwide renown and the adulation of Italians. Faith in his prowess was so strong that doubt, confusion, and dismay seized even the Neapolitan court. Six weeks later, he marched against Messina in the east of the island. By the end of July, only the citadel resisted him.

Having finished the conquest of Sicily, he crossed the Straits of Messina, under the nose of the Neapolitan fleet, and marched northward. Garibaldi's progress was met with more celebration than resistance, and on September 7th he entered the capital city of Naples. However, he had never defeated the Bourbon king, Francis II. Most of the Sicilian army remained loyal, and had gathered north of the river Volturno. Though by then Garibaldi's volunteers numbered some 25,000, they could not oppose the Sicilians. The volunteers had some success on the 1st of October, but Francis II retired only the next day, after the arrival of the Sardinian army under the command of Victor Emmanuel.

Garibaldi deeply disliked the Sardinian Prime Minister, Camillo di Cavour. To an extent, he simply mistrusted Cavour's pragmatism and realpolitik, but he also bore a personal grudge for trading away his home city of Nice to the French the previous year. On the other hand, he felt attracted toward the Sardinian monarch, who in his opinion had been chosen by Providence for the liberation of Italy. In his famous meeting with Victor Emmanuel II at Teano on October 26, 1860, Garibaldi greeted him as King of Italy and shook his hand. He resigned the next day. Garibaldi rode into Naples at the king's side on November 7, then retired to the rocky island of Caprera, refusing to accept any reward for his services.

Garibaldi's fellow revolutionaries were not satisfied. With the motto "Free from the Alps to the Adriatic," the unification movement set its gaze on Rome and Venice. Mazzini was discontented with the perpetuation of monarchial government, and continued to agitate for a republic. Garibaldi, frustrated at inaction by the king, and bristling over perceived snubs, organized a new venture. This time, he intended to take on the Papal States.

A challenge against the Pope's temporal domain was viewed with great distrust by Catholics around the world, and the French emperor Napoleon III had guaranteed the independence of Rome from Italy by stationing French troops in Rome. Victor Emmanuel was wary of the international repercussions of attacking the Papal States, and discouraged his subjects from participating in revolutionary ventures with such intentions. Nonetheless, Garibaldi believed he had the secret support of his government.

In June of 1862, he sailed from Genoa and landed at Palermo, seeking to gather volunteers for the impending campaign. An enthusiastic party quickly joined him, and he turned for Messina, hoping to cross to the mainland there. When he arrived, he had a force of some two thousand, but the garrison proved loyal to the king's instructions and barred his passage. They turned south and set sail from Catania, where Garibaldi declared that he would enter Rome as a victor or perish beneath its walls. He landed at Melito on August 14, and marched at once into the Calabrian mountains.

Far from supporting this endeavor, the Italian government was quite disapproving. General Cialdini dispatched a division of the regular army, under Colonel Pallavicino, against the volunteer bands. On August 28 the two forces met in the rugged Aspromonte. One of the regulars fired a chance shot, and several volleys followed, killing a few of the volunteers. The fighting ended quickly, as Garibaldi forbade his men to return fire on fellow subjects of the Kingdom of Italy. Many of the volunteers were taken prisoner, including Garibaldi, who had been wounded.

A government steamer took him to Varignano, where he was held in a sort of honorable imprisonment, and was compelled to undergo a tedious and painful operation for the healing of his wound. His venture had failed, but he was at least consoled by Europe's sympathy and continued interest. After being restored to health, he was released and allowed to return to Caprera.

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Garibaldi volunteered his services to President Abraham Lincoln and was invited to serve as a brigadier general. Garibaldi declined, stating he would only accept command of the entire Union Army, and the offer was quietly withdrawn.

Garibaldi took up arms again in 1866, this time with the full support of the Italian government. The Austro-Prussian War had broken out, and Italy had allied with Prussia against Austria-Hungary in the hope of taking Venetia from Austrian rule. Garibaldi gathered again his Hunters of the Alps, now some 40,000 strong, and led them into the Tyrol. He defeated the Austrians at Bezzecca and made for Trento.

The Italian regular forces, on the other hand, suffered defeat by land and sea. Austria did cede Venetia to Italy, but it was compelled to do so not by Italy's poor showing, but by Prussia's successes on the northern front. Garibaldi's advance through Trentino was for nought and he was ordered to stop his advance to Trento. He answered with a short telegram "Obbedisco" (I obey).

After the war, Garibaldi led a political party that agitated for the capture of Rome, the peninsula's ancient capital. In 1867, he again marched on the city, but the Papal army, supported by a French auxiliary force, proved a match for his badly-armed volunteers. He was taken prisoner, held captive for a time, and then again returned to Caprera.

At the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, French troops withdrew from Rome, and the Italians captured the Papal States without Garibaldi's assistance. Following the wartime collapse of the Second French Empire, Garibaldi led a force of volunteers against Prussia in support of the new French Third Republic, as he considered France the nation of freedom.

Garibaldi statue in Washington Square Park, Lower Manhattan, New York City, New York, USAOn his deathbed, Garibaldi asked that his bed be moved to where he could gaze at the emerald and sapphire sea.

Garibaldi's popularity, his skill at rousing the masses, and his military exploits are all credited with making the unification of Italy possible. He also served as a global exemplar of mid-19th century revolutionary nationalism and liberalism. But following the liberation of southern Italy from the Neapolitan monarchy, Garibaldi chose to sacrifice his liberal republican principles for the sake of unification.

Garibaldi subscribed to the anti-clericalism common among Latin liberals and did much to circumscribe the temporal power of the Papacy. His personal convictions bordered on atheism; he wrote in 1882, "Man created God, not God Man." An active freemason, Garibaldi had little use for rituals, but thought of masonry as a network to unite progressive men as brothers both within nations and as members of a global community.

Giuseppe Garibaldi died on the Italian island of Caprera in 1882, where he was interred. Five ships of the Italian Navy have been named after him, among which a World War II cruiser and the current flagship, the aircraft carrier Giuseppe Garibaldi.

Statues of his likeness, as well as the handshake of Teano, stand in many Italian squares, and in other countries around the world. On the top of the Janiculum hill in Rome, there is a statue of Garibaldi on horse-back with his face turned in the direction of the Vatican, an allusion[citation needed] to his ambition to conquer the Papal States. In Brazil, the city of Garibaldi is named after him. Garibaldi, Oregon in the USA was also named for the Italian patriot in 1867. Mt. Garibaldi, one the tallest and most impressive peaks part of the Garibaldi Belt of volcanic mountains located north of Vancouver, Canada, is also named after him.

It is said that the Garibaldi biscuit is named for the famous commander, who gave it to his men. His red-shirted volunteers also lent his name to the garibaldi, a North American fish with a distinctive orange color. A pub located in Bourne End, Buckinghamshire, England is also named after the biscuit or, according to some, for the general. In Italian, the word garibaldino refers not only to a follower of Garibaldi: in tribute to the hero's exploits, it is also an adjective meaning bold or audacious. The red strip of the English football club Nottingham Forest is sometimes referred to as 'the garibaldi'. Garibaldi is known to have stayed in Tynemouth House, Tynemouth, in the north east of England, now part of The King's School, Tynemouth. A room in the house is subsequently named The Garibaldi Room.

GARIBALDI, Giuseppe, Italian patriot, born in Nice, 4 July, 1807; died in Caprera, 2 June, 1882. He followed the sea from his earliest youth, and in 1836 went to Rio Janeiro, where he engaged in the coasting trade. In 1837 he offered his services to the revolted Brazilian province of Rio Grande do Sul, and commanded a fleet of gun-boats. After many daring exploits he was forced to burn his vessels, and went to Montevideo, where he became a broker and teacher of mathematics, He took service in Uruguay in the war against Rosas, and was given the command of a small naval force which he was obliged to abandon after a battle at Costa Brava 15 and 16 June, 1842. Garibaldi then organized the famous Italian legion, with which for four years he fought numerous battles for the republic. In 1845 he commanded an expedition to Salto, where he established his headquarters, and toward the end of the year he resisted with 500 men for three days the assault of Urquiza's army of 4,000 men. On 8 February, 1846, he repelled at San Antonio, with scarcely 200 men, General Servando Gomez with 1., 200 soldiers. In 1847, when he heard of Italy's rising against Austrian dominion, he went to assist his country, accompanied by a portion of the Ital-Jan legion ; but, after taking part in several unsuccessful attempts, including the defence of Rome against the French in 1849, he sailed in June, 1850, for New York. On Staten island he worked for a time with a countryman manufacturing candles and soap, and in 1851 he went by way of Central America and Panama to Callao, whence he sailed in 1852 in command of a vessel for China. Early in 1854 he returned to Italy, where he lived quietly in the island of Caprera. At the opening of war against Austria in 1859 he organized the Alpine chasseurs, and defeated the enemy in several encounters. After the peace of Villafranca he began preparations for the expedition which was secretly encouraged by the government. Having conquered Sicily and being proclaimed dictator, he entered Naples in triumph on 7 September, 1860, but afterward resigned the dictatorship and proclaimed Victor Emmanuel king of Italy, declining all proffered honors and retiring to Caprera. In 1862 he planned the rescue of Rome from the French, and again invaded Calabria from Sicily, but was wounded and captured at Aspromonte, 29 August, 1862, and sent back to Caprera. In June, 1866, during the Austro-Prussian war, he commanded for a short time an army of volunteers, and on 14 October, 1867, he undertook another expedition to liberate Rome, but was routed by the Papal troops and the French. He entered the service of the French republic in 1870, and he organized and commanded the chasseurs of the Vosges. In 1871 he was elected to the Italian parliament, and took an active part in poll-tics till the end of his life. In 1888 the Italians in New York erected a bronze statue of him which was unveiled in Washington square, 4 June, 1888. He wrote several novels, including "Cantoni il volontario " (Genoa, 1870) ; " Clelia, ovvero il governo monaco; Roma del secolo XIX" (1870), which in the same year was translated into English under the title of " The Rule of the Monk, or Rome in the 19th Century"; " Il frate dominatore" (1873) ; and a poem, " Le Mila di Marsala" (1873). Many biographies of Garibaldi have been written and translated into English, including those by W. Robson (London, 1860), by Theodore Dwight (New York, 1860), and by Mrs. Gaskell (London, 1862). An autobiography appeared after his death, under the title " Garibaldi ; Memorie autobiografiche" (Florence, 1888).

July 4, 1807 - June 2, 1882

was an Italian nationalist and soldier of the Risorgimento. He personally led many of the military campaigns that brought about the formation of a unified Italy. He was called the "Hero of the Two Worlds," in tribute to his military adventures in South America and Europe.He was born in the coastal city of Nice, and reared to a life on the sea. The city was then part of Savoy, in the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia.

Influenced by Giuseppe Mazzini, an impassioned proponent of Italian nationalism, he joined the Carbonari revolutionary association. He participated in a failed republican uprising in Piedmont in 1834. Sentenced to death, he escaped to South America. In 1839, he joined the rebel cause in the War of Tatters revolt in Brazil, which had broken out a few years before. Six years of tenacity proved unsuccessful, and the rebels finally surrendered in 1845. He later commanded the Uruguayan navy in defence against Juan Manuel de Rosas of Argentina, who was trying to reannex the country.

Garibaldi returned to Italy in the tumult of the revolutions of 1848, and offered his services to Charles Albert of Sardinia. The monarch displayed some liberal inclinations, but treated Garibaldi with coolness and distrust. Meanwhile, a Roman Republic had been proclaimed in the Papal States, but an Austrian and French force threatened to topple it. At Mazzini's urging, Garibaldi took up the command of the defence of Rome. His wife, Anita, fought with him. Despite their effort, the city fell, and Garibaldi was forced to flee to the north, hunted by the Austrian troops that had entered into the Papal States. He eventually managed to escape abroad, but he had lost Anita. In 1850 he became a resident of New York, where he met Antonio Meucci. For some time he worked in a manufactory of candles on Staten Island, and afterwards made several voyages on the Pacific.

Garibaldi returned to Italy in 1854. In 1859, the Austro-Sardinian War broke out through the machinations of the Sardinian government. Garibaldi was appointed major general, and formed a volunteer unit named the Hunters of the Alps. With his volunteers, he won victories over the Austrians at Varese, Como, and other places. One outcome of the war, though, left Garibaldi very displeased. His home city of Nice was surrendered to the French, in return for crucial military assistance.

Part 3: Campaign of 1860

At the beginning of April 1860, uprisings in Messina and Palermo in the absolutist Kingdom of the Two Sicilies provided Garibaldi with an opportunity. He gathered about a thousand volunteers (called i Mille, or, as popularly known, the "Red Shirts") in two ships, and landed at Marsala, on the westernmost point of Sicily, on May 11.Conquest of Sicily

Swelling the ranks of his army with scattered bands of local rebels, Garibaldi defeated an opposing army at Catalafimi on May 13. The next day, he declared himself dictator of Sicily in the name of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy. He advanced then to Palermo, the capital of the island, and launched a siege on May 27. He had the support of many of the inhabitants, who rose up against the garrison, but before the city could be taken, reinforcements arrived and bombarded the city nearly to ruins. At this time, a British admiral intervened and facilitated an armistice, by which the Neapolitan royal troops and warships departed and surrendered the city.Garibaldi had won a signal victory. He gained worldwide renown and the adulation of Italians. Faith in his prowess was so strong that doubt, confusion, and dismay seized even the Neapolitan court. Six weeks later, he marched against Messina in the east of the island. By the conclusion of July, only the citadel resisted him.

Crossing to the Mainland

Having finished the conquest of Sicily, he crossed the Straits of Messina, under the nose of the Neapolitan fleet, and marched northward. Garibaldi's progress was met with more celebration than resistance, and on September 7th he entered the capital city of Naples. However, he had never defeated the king, Francis II. Most of the army remained loyal, and had gathered north of the river Volturno. Though by then his volunteers numbered some 25,000, Garibaldi could not oppose it. A major battle was fought on the Volturno on the 1st and 2nd of October, but the bulk of the fighting was left to the Sardinian army under the command of Victor Emmanuel.

Garibaldi deeply disliked the Sardinian Prime Minister, Camillo di Cavour. To an extent, he simply mistrusted Cavour's pragmatism and realpolitik, but he also bore a personal grudge for trading away his home city of Nice to the French the previous year. On the other hand, he felt attracted toward the king, who in his opinion had been chosen by Providence for the liberation of Italy. He greeted Victor Emmanuel with the title of King of Italy, and resigned the next day, telegraphing the single word Obbedisco ("I obey"). Garibaldi rode into Naples at the king's side, then retired to the rocky island of Caprera, refusing to accept any reward for his services.

Garibaldi's fellow revolutionaries were not satisfied. With the motto "Free from the Alps to the Adriatic," the unification movement set its gaze on Rome and Venice. Mazzini was discontented with the perpetuation of monarchial government, and continued to agitate for a republic. Garibaldi, frustrated at inaction by the king, and bristling over perceived snubs, organized a new venture. This time, he intended to take on the Papal States.

Part 4: Expedition Against Rome

A challenge against the Pope's temporal domain was viewed with great distrust by Catholics around the world, and French troops were stationed in Rome. Victor Emmanuel was wary of the international reprecussions of attacking the Papal States, and discouraged his subjects from participating in revolutionary ventures with such intentions. Nonetheless, Garibaldi believed he had the secret support of his government.In June of 1862, he sailed from Genoa and landed at Palermo, seeking to gather volunteers for the impending campaign. An enthusiastic party quickly joined him, and he turned for Messina, hoping to cross to the mainland there. When he arrived, he had a force of some two thousand, but the garrison proved loyal to the king's instructions and barred his passage. They turned south and set sail from Catania, where Garibaldi declared that he would enter Rome as a victor or perish beneath its walls. He landed at Melito on August 14, and marched at once into the Calabrian mountains.

Far from supporting this endeavor, the Italian government was quite disapproving. General Cialdini dispatched a division of the regular army, under Colonel Pallavicino, against the volunteer bands. On August 28 the two forces met in the rugged Aspromonte. One of the regulars fired a chance shot, and several volleys followed, killing a few of the volunteers. The fighting ended quickly, as Garibaldi forbade his men to return fire on fellow subjects of the Kingdom of Italy. Many of the volunteers were taken prisoner, including Garibaldi, who had been wounded.

A government steamer took him to Varignano, where he was held in a sort of honorable imprisonment, and was compelled to undergo a tedious and painful operation for the healing of his wound. His venture had failed, but he was at least consoled by Europe's sympathy and continued interest. After being restored to health, he was released and allowed to return to Caprera.

Part 5: In the Austro-Prussian War and Afterward

Garibaldi took up arms again in 1866, this time with the full support of the Italian government. Italy had allied with Prussia against Austria-Hungary, seeking to take Venetia from Austrian rule. He gathered again his Hunters of the Alps, now some 40,000 strong, and led them into the Tyrol. While the Italian regular forces suffered defeat by land and sea, Garibaldi defeated the Austrians at Bezzecca and made for Trento.Italy did annex Venetia, though this was due not to its own military prowess but to Prussia's. Garibaldi's success in Trentino was for nought.

Garibaldi now led a political party that agitated for the capture of Rome, the peninsula's ancient capital. In 1867, he again marched on the city, but the Papal army, supported by a French auxiliary force, proved a match for his badly-armed volunteers. He was taken prisoner, held captive for a time, and then again returned to Caprera. French troops withdrew from Rome in 1870, and the Italians captured the Papal States without Garibaldi's assistance.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871, he led a force of volunteers in support of the new French republic.

Part 6: Legacy

Garibaldi's popularity, his skill at rousing the masses, and his military exploits are all credited with making the unification of Italy possible.He died on Caprera, where he was interred. Five ships of the Italian Navy have been named after him, among which the current flagship, the aircraft carrier Giuseppe Garibaldi.