Franco

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

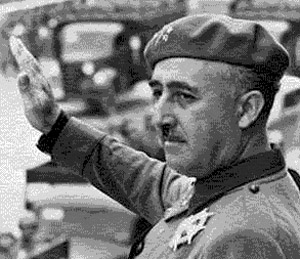

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

Francisco Franco—Dictator of Spain

December 4, 1892, El Ferrol, Spain, 12:30 AM, LMT. (Source: registered at the parish church) Died, November 19, 1975, Madrid.

(Ascendant, Virgo; Sun and retrograde Mercury in Sagittarius; Moon in Gemini conjunct Neptune and Pluto also in Gemini; Venus conjunct Uranus in Scorpio; Mars in Pisces; Jupiter in Aries; Saturn in Libra)http://www.astrotheme.fr/portraits/z63PUhze22X5.htm -- has 22 Virgo rising

Franco, an excellent organizer and a puristic idealist (with four planets plus Ascendant in signs through which the sixth ray is transmitted), expressed the seventh, sixth and first rays. He rose through the ranks to become chief of staff of he army in 1935. He commanded the rebel forces during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) leading the revolt against the Communist-inspired socialist government and planning the offensives which gave victory to the rebel forces. After the War he became dictator of Spain, maintaining a strong anti-Communist policy and using repressive, censorious methods.

It is well to remember that the rays of Spain are the sixth ray soul and the seventh ray personality—two of Franco’s important rays. Yes, withal, the first ray must be considered as a major ray, since the Tibetan informs us that Franco, along with Stalin and Hitler were expressions of the “Shamballa Force”.

I am responsible only to God and history.

“[Communists] should be crushed like worms.”

“There will be no communism.”

“American students are more frank compared with Asian and Filipino students. It's taught me how to try and understand students and how to best deal with them.”

“I'm still dead!”

"Our regime is based on bayonets and blood, not on hypocritical elections."

Franco was born in Ferrol, Galicia, Spain on December 4, 1892.

His father Nicolás Franco Salgado-Araujo was a Navy paymaster. His mother Pilar Bahamonde Pardo de Andrade also came from a family with naval tradition. He was sibling to Nicolás Franco Bahamonde, navy officer and diplomat; a sister, Pilar Franco Bahamonde, the latter a well-known socialite; and another brother, Ramón Franco, a pioneer aviator who was hated by many of Franco's supporters.

His hometown was officially known as El Ferrol del Caudillo from 1938 to 1982. During his youth he suffered at the hands of his aggressive, alcoholic father, and it is argued by many that these experiences in his early years are what set him on the road to the atrocities he was responsible for in later life.

Franco was to follow his father into the navy, but entry into the Naval Academy was closed from 1906 to 1913. To his father's chagrin, he decided to join the army. In 1907, he entered the Infantry Academy in Toledo, where he graduated in 1910. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant.

Two years later, he obtained a commission to Morocco. Spanish efforts to physically occupy their new African protectorate provoked a long protracted war (from 1909 to 1927) with native Moroccans. Tactics at the time resulted in heavy losses among Spanish military officers, but also gave the chance of earning promotion through merit. This explains the saying that officers would get either la caja o la faja (a coffin or a general's sash).

Franco soon gained a reputation as a good officer. He joined the newly formed regulares colonial native troops with Spanish officers, who acted as shock troops.

In 1916, at the age of 23 and already a captain, he was badly wounded in a skirmish at El Biutz. This action marked him permanently in the eyes of the native troops as a man of baraka (good luck). He was also proposed unsuccessfully for Spain's highest honor for gallantry, the coveted Cruz Laureada de San Fernando. Instead, he was promoted to major (comandante), becoming the youngest staff officer in the Spanish Army.

From 1917 to 1920 he was posted on the Spanish mainland. That last year, Lieutenant Colonel José Millán Astray, a histrionic but charismatic officer, founded the Legión Extranjera, along similar lines to the French Foreign Legion. Franco became the Legión's second-in-command and returned to Africa.

In summer 1921, the overextended Spanish army suffered (July 24) a crushing defeat at Annual at the hands of the Rif tribes led by the Abd el-Krim brothers. The Legión symbolically, if not materially, saved the Spanish enclave of Melilla after a gruelling three-day forced march led by Franco. In 1923, already a lieutenant colonel, he was made commander of the Legión.

The same year he married María del Carmen Polo y Martínez Valdés and they had one child, a daughter, María del Carmen, born in 1926. As a special mark of honour, his best man (padrino) at the wedding was King Alfonso XIII, a fact which would mark him, during the Republic as a monarchical officer.

Promoted to colonel, Franco led the first wave of troops ashore at Alhucemas in 1925. This landing in the heartland of Abd el-Krim's tribe, combined with the French invasion from the south, spelled the beginning of the end for the shortlived Republic of the Rif.

Becoming the youngest general in Spain in 1926, Franco was appointed in 1928 director of the newly created Joint Military Academy in Zaragoza, a common college for all Army cadets.

During the Second Spanish Republic

At the fall of the monarchy in 1931, in keeping with his prior apolitical record, he did not take any remarkable attitude. But the closing of the Academy in June by then War Minister Manuel Azaña provoked the first clash with the Republic. Azaña found Franco's farewell speech to the cadets [1]insulting, resulting in Franco being without a post for six months, and under surveillance.

On February 5, 1932 he was given a command in La Coruña. Franco avoided being involved in Jose Sanjurjo's attempted coup that year. As a side result of Azaña's military reform, in January 1933 Franco was relegated from the first to the 24th in the list of Brigadiers; conversely, the same year (February 17), he was given the military command of the Balearic Islands—a post above his rank.

The Asturias Uprising

New elections were held in October 1933 which resulted in a center-right majority. In opposition to this government, a revolutionary movement broke out October 5, 1934. This attempt was rapidly quelled in most of the country, but gained a stronghold in Asturias, with the support of the miners' unions. Franco, already general of a Division and assessor to the war minister, was put in command of the operations directed to suppress the insurgency. The forces of the Army in Africa were to carry the brunt of the operations, with General Eduardo López Ochoa as commander in the field. After two weeks of heavy fighting (and a death toll estimated between 1,200 and 2,000), the rebellion was suppressed.

The uprising and, in general, the events that led over the next two years to the civil war, are still under heavy debate (between, for example, Enrique Moradiellos and Pio Moa: see [2], [3], or [4]). Nonetheless, it is universally agreed that the insurgency in Asturias sharpened the antagonism between left and right. Franco and Lopez Ochoa—who up to that moment was seen as a left-leaning officer—were marked by the left as enemies. Lopez Ochoa was persecuted, jailed, and finally killed at the start of the war.

Some time after these events, Franco was briefly commander-in-chief of the Army of Africa (from February 15, 1935 onwards), and from May 19, 1935 on, Chief of the General Staff, the top military post in Spain.

The drift to war

After the ruling coalition collapsed amid corruption scandals (the estraperlo case), new elections were scheduled. Two wide coalitions formed: the Popular Front on the left, from Republicans to the Communists, and the Frente Nacional, on the right, from the centre radicals to the conservative Carlists. On February 16, 1936, the left won by a narrow margin[5]. The days after were marked by near chaotic circumstances. Franco lobbied unsuccessfully to have a state of emergency declared, with the stated purpose to quell the disturbances and allow an orderly vote recount. Instead, Franco was sent (February 23) as military commander of the Canary Islands, a distant place with few troops under his command.

Meanwhile, a conspiracy led by Emilio Mola was taking shape. Franco was contacted, but maintained an ambiguous attitude almost up to July. On June 23, 1936, he even wrote to the head of the government, Casares Quiroga, offering to quell the discontent in the army, but was not answered. The other rebels were determined to go ahead whatever con Paquito o sin Paquito (with Franco or without him) and after various postponements, July 18 was fixed as the date of the uprising. The situation reached a point of no return and, as presented to Franco by Mola, the coup was unavoidable and he had to choose a side. He decided to join the rebels and was given the task of commanding the African Army. A privately owned DH 89 De Havilland Dragon Rapide (still referred to in Spain as the Dragon Rapide) was chartered in England July 11 to take him to Africa.

The assassination of the right-wing opposition leader José Calvo Sotelo by government police troops (quite possibly acting on their own, such in the case of José Castillo) precipitated the uprising. On July 17, one day earlier than planned, the African Army rebelled, detaining their commanders. On July 18 Franco published a manifesto [6] and left for Africa, where he arrived the next day to take command.

A week later, the rebels, who soon called themselves the Nacionales (literally Nationals, but almost always referred to in English as Nationalists), controlled only a third of Spain, and most navy units remained under control of the opposition Republican forces, which left Franco isolated. The coup had failed, but the Spanish Civil War had begun.

The first months

The first days of the rebellion were marked with a serious need to secure control over the Protectorate. On one side, Franco managed to win the support of the natives and their (nominal) authorities, and on the other to ensure his control over the army. This led to the execution of some senior officers loyal to the republic (one of them his own first cousin) [7]. Franco had to face the problem of how to move his troops to the Iberian Peninsula, because most units of the Navy had remained in control of the republic and were blocking the Strait of Gibraltar. From the July 20 onward he was able, with a small group of airplanes, to initiate an air bridge to Seville, where his troops helped to ensure the rebel control of the city. Through representatives, he started to negotiate with the United Kingdom, Germany and Italy for military support, and above all for more aeroplanes. Negotiations were successful with the last two on July 25, and aeroplanes began to arrive in Tetouan on August 2. On August 5, Franco was able to break the blockade with the newly arrived air support, successfully deploying a ship convoy with some 2,000 soldiers.

In early August, the situation in western Andalusia was stable enough to allow him to organize a column (some 15,000 men at its height), under the command of then Lieutenant-Colonel Juan Yagüe, which would march through Extremadura towards Madrid. August 11, Mérida was taken, and August 15 Badajoz, thus joining both nationalist-controlled areas.

On September 21, with the head of the column at the town of Maqueda (some 80 km away from Madrid), Franco ordered a detour to free the besieged garrison at the Alcázar of Toledo, which was achieved September 27. This decision was controversial even then, but resulted in an important propaganda success, both for the fascist party and for Franco himself.

Rise to power

The designated leader of the uprising, Gen. José Sanjurjo had died on July 20 in an air crash. The nationalist leaders managed to overcome this through regional commands: (Mola in the North, Queipo in Andalusia, Franco with an independent command and Cabanellas in Aragon), and a coordinating junta nominally led by the last, as the most senior general. On September 21, it was decided that Franco was to be commander-in-chief, and September 28, after some discussion, also head of government. On October 1, 1936 he was publicly proclaimed as Generalísimo of the Fascist army and Jefe del Estado (Head of State).

Military command

From that time until the end of the war, Franco personally guided military operations. After the failure to take Madrid in November 1936, Franco settled to a piecemeal approach to winning the war, rather than bold manouevering. As with his decision to relieve the garrison at Toledo, this approach has been subject of some debate; some of his decisions, such as in June 1938 when he preferred to head for Valencia instead of Catalonia, remain particularly controversial.

His army was supported by troops from Nazi Germany (the Condor Legion) and, above all, Fascist Italy (Corpo Truppe Volontarie), but the degree of influence of both powers on Franco's direction of war seems to have been very limited. António de Oliveira Salazar's Portugal also openly assisted the Fascists from the start.

Political command

He managed to fuse the ideologically incompatible national-syndicalist Falange ("phalanx", a far-right Spanish political party with ideology similar to that of Mussolini's movement) and the Carlist monarchist parties under his rule.

From early 1937 every death sentence had to be signed (or acknowledged) by Franco.

The end of the war

On March 4, 1939 an uprising broke out within the Republican camp, claiming to forestall an intended Communist coup by prime minister Juan Negrín. Led by Colonel Segismundo Casado and Julián Besteiro, the rebels gained control over Madrid. They tried to negotiate a settlement with Franco, who refused anything but unconditional surrender. They gave way; Madrid was occupied on March 27, and the republic fell. The war officially ended on April 1, 1939.

However, during the 1940s and 1950s, guerrilla resistance to Franco (known as "the maquis") was widespread in many mountainous regions. In 1944, a group of republican veterans that also fought in the French resistance against the nazis invaded the Val d'Aran in northwest Catalonia, but they were easily defeated.

Spain under Franco

Spain was bitterly divided and economically ruined as a result of the civil war. After the war a very harsh repression began, with thousands of summary executions, an unknown number of political prisoners and tens of thousands of people in exile, largely in France and Latin America. The 1940 shooting of the president of the Catalan government, Lluís Companys, was one of the most notable cases of this early repression, while the major groups targeted were real and suspected leftists, ranging from the moderate, democratic left to Communists and Anarchists, the Spanish intelligentsia, atheists and military and government figures that had remained loyal to the Madrid government during the war. The bloodshed in Spain did not end with the cessation of hostilities, many political prisoners suffered execution by the firing squad, under the accusation of treason.

World War II

In September 1939, World War II broke out in Europe, and although Adolf Hitler met Franco in Hendaye, France (October 23, 1940), to discuss Spanish entry on the side of the Axis, Franco's demands (food, military equipment, Gibraltar, French North Africa, etc.) proved too much and no agreement was reached. Contributing to the disagreement was an ongoing dispute over German mining rights in Spain. Some historians argue that Franco made demands that he knew Hitler would not accede to in order to stay out of the war. Other historians argue that he simply had nothing to offer the Germans. After the collapse of France in June 1940, Spain adopted a pro-Axis non-belligerency stance (for example, he offered Spanish naval facilities to German ships) until returning to complete neutrality in 1943 when the tide of the war had turned decisively against Germany. Some volunteer Spanish troops (the División Azul, or "Blue Division")—not given official state sanction by Franco—went to fight on the Eastern Front under German command. On June 14, 1940, the Spanish forces in Morocco occupied Tangiers (a city under the rule of the League of Nations) and did not leave it until 1942.

During the war Franco's Spain also proved to be an escape route for several thousand European Jews fleeing deportation from occupied France to concentration camps. Spanish diplomats extended their protection to Sephardi Jews from Eastern Europe, especially in Hungary.[8][9]

Post-War

With the end of World War II, Franco and Spain were forced to suffer the economic consequences of the isolation imposed on it by nations such as the United Kingdom and the United States. This situation ended in part when, due to Spain's strategic location in light of Cold War tensions, the United States entered into a trade and military alliance with Spain. This historic alliance commenced with United States President Eisenhower's visit in 1953 which resulted in the Pact of Madrid. This launched the so-called "Spanish Miracle," which developed Spain from autarky into capitalism. Spain was admitted to the United Nations in 1955. In spite of this opening, Franco almost never left Spain once in power.

Lacking any strong ideology, Franco initially sought support from National syndicalism (nacionalsindicalismo) and the Roman Catholic Church (nacionalcatolicismo). His coalition-ruling single party, the Movimiento Nacional, was so heterogeneous as to barely qualify as a party at all, and certainly not an ideological monolith like the Fascio di Combattimento (Fascist Party) or the ruling block of Antonio Salazar. His Spanish State was chiefly a conservative—even traditionalist—rightist regime, with emphasis on order and stability, rather than a definite political vision.

In 1947 Franco proclaimed Spain a monarchy, but did not designate a monarch. This gesture was largely done to appease monarchist factions within the Movimiento. Although a self-proclaimed monarchist himself, Franco had no particular desire for a king. As such, he left the throne vacant, with himself as de facto regent. He wore the uniform of a captain general (a rank traditionally reserved for the King) and resided in the Pardo Palace, not to be confused with the Museo del Prado. In addition he appropriated the kingly privilege of walking beneath a canopy, and his portrait appeared on most Spanish coins. Indeed, although his formal titles were Jefe del Estado (Chief of State) and Generalísimo de los Ejércitos Españoles (Generalísimo of the Spanish Armed Forces). He had originally intended any government that succeeded him to be much more authoritarian than the previous monarchy. This is indicated in his use of "by the grace of God" in his official title. It is a technical, legal phrase which indicates sovereign dignity in absolute monarchies, and is only used by monarchs.

During his rule non-government trade unions and all political opponents across the political spectrum, from communist and anarchist organizations to liberal democrats and Catalan or Basque nationalists, were suppressed. The only legal "trade union" was the government-run Sindicato Vertical.

In order to build a uniform Spanish nation, the public usage of languages other than Spanish (especially Catalan, Galician and Basque languages) was strongly repressed. Language politics in Francoist Spain stated that all government, notarial, legal and commercial documents were drawn up exclusively in Spanish and any written in other languages were deemed null and void. The usage of other than Spanish languages was banned on road and shop signs, advertising and in general all exterior iimages of the country.

All cultural activities were subject to censorship, and many were plainly forbidden on various, many times spurious, grounds (political or moral). This cultural policy relaxed with time, most notably after 1960.

The enforcement by public authorities of strict Catholic social mores was a stated intent of the regime, mainly by using a law (the Ley de Vagos y Maleantes, Vagancy Act) enacted by Azaña [10]. The remaining nomads of Spain (Gitanos and Mercheros like El Lute) were especially affected.

In 1954, homosexuality and prostitution were, through this law, made criminal offenses. [11]. Its application was inconsistent.

In every town there was a constant presence of Guardia Civil, a military police force, who patrolled in pairs with submachine guns, and functioned as his chief means of control. He was constantly obsessed with a Masonic conspiracy. In popular imagination, he is often remembered as in the black and white iimages of No-Do newsreels, inaugurating a reservoir, hence his nickname Paco Ranas (Paco—a familiar form of Francisco—"the Frog"), or catching huge fish from the Azor yacht during his holidays.

Spanish Civil War

Famous quote: "Our regime is based on bayonets and blood, not on hypocritical elections."

In 1968, due to the United Nations' pressure on Spain, Franco granted Equatorial Guinea its independence.

In 1969 he designated Prince Juan Carlos de Borbón with the new title of Prince of Spain as his successor. This came as a surprise for the Carlist pretender to the throne, as well as for Juan Carlos's father, Don Juan, the Count of Barcelona, who technically had a superior right to the throne. By 1973 Franco had given up the function of prime minister (Presidente del Gobierno), remaining only as head of the country and as commander in chief of the military forces. As his final years progressed tension within the various factions of the Movimiento would consume Spanish political life, as varying groups jockeyed for position to control the country's future.

Franco died on November 20, 1975,

at the age of 82—

the same date as José Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of the Falange.It is suspected that the doctors were ordered to keep him barely alive by artificial means until that symbolic date. The historian, Ricardo de la Cierva, says that on the 19th around 6 p.m. he was told that Franco had already died. Franco is buried at Santa Cruz del Valle de los Caídos, a site built by forced prisoners of the Spanish Civil War as the tomb for unknown soldiers killed during war.

Spain after Franco

Franco's successor as head of state was the current Spanish monarch, Juan Carlos. Though much beloved by Franco, the King held liberal political views which earned him suspicion among conservatives who hoped he would continue Franco's policies. Instead, Juan Carlos would proceed to restore democracy in the nation, and help crush an attempted military coup in 1981.

Since Franco's death, almost all the placenames named after him (most Spanish towns had a calle del Generalísimo) have been changed. This holds particularly true in the regions ruled by parties heir to the Republican side, while in other regions of central Spain rulers have preferred not to change such placenames, arguing they would rather not stir the past. Most statues or monuments of him have also been removed, and, in the capital, Madrid, the last one standing was removed in March 2005.

He was declared a saint by Clemente Domínguez y Gómez (self-declared Pope Gregory XVII) of the Palmarian Catholic Church, a right-wing Catholic mysticalist sect largely based in Spain. Franco's canonization is not recognized by the Roman Catholic Church.

Franco in culture

At the time of Franco's death, on the then-new American television show Saturday Night Live as part of its satiric newscast Weekend Report, Chevy Chase announced, "Despite Franco's death and an expected burial tomorrow, doctors say the dictator's health has taken a turn for the worse." [12] The segment also included a statement by Richard Nixon that "General Franco was a loyal friend and ally of the United States", accompanied by a photo of Franco and Adolf Hitler standing together and giving the Fascist/Nazi salute, similar to this one [13]. Over the next several weeks it became a running joke for Chase to announce as part of the newscast "This just in: Generalissimo Francisco Franco is still dead"! [14]