Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

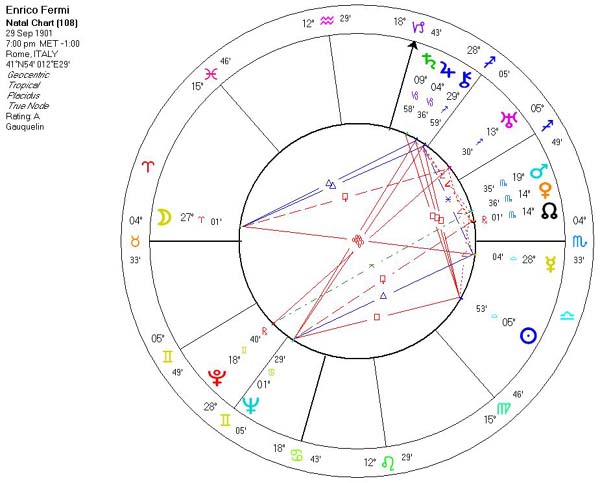

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images Physiognomic Interpretation

There are two possible outcomes: if the result confirms the hypothesis, then you've made a measurement. If the result is contrary to the hypothesis, then you've made a discovery.

It is no good to try to stop knowledge from going forward. Ignorance is never better than knowledge.

If I could remember the names of all these particles, I'd be a botanist.

On December 2, 1942, Enrico Fermi and his team of scientists harnessed the atom and opened the door to new scientific and technological realms. His achievement allowed the U.S. to produce the atomic bomb that helped end World War II. Now, more than fifty years later, nuclear energy provides a significant part of the world's electrical power, and radioactive materials are used for hundreds of industrial, agricultural, and medical applications-from food preservation to cancer therapy, checking the integrity of welds in pipelines and bridge supports, and gauges that measure the thickness of coatings applied to paper.

Fermi was born in Rome in 1901 and received his doctorate from the University of Pisa in 1922. During 1923 to 1924, he studied in Gottingen, Germany, with Max Born, and in Leiden, The Netherlands, with Paul Ehrenfest. From 1924 to 1926, Fermi lectured in mathematical physics and mechanics at the University of Florence. He became the first professor of theoretical physics at the University of Rome, where he taught for 12 years.

In 1938, Fermi traveled to Stockholm to receive the Nobel Prize "for his identification of new radioactive elements produced by neutron bombardment and his discovery, made in connection with this work, of nuclear reactions effected by slow neutrons." Fermi's wife Laura, in her book Atoms in the Family*, wrote, "Four years of patient researches; the broken and the unbroken tubes full of beryllium powder and radon; the strenuous races along the hall of the physics building to rush element after element to the Geiger counters; the efforts to understand nuclear processes, and the many tests to prove the theories ... these had won the Nobel Prize for Enrico."*

By 1938, Fascist Italy had become intolerable to Fermi. He used his trip to Stockholm as an opportunity to flee. He and his family sailed directly to the United States, where he had visited many times before. In the months before his Stockholm trip, he had sought teaching positions in America and had received offers from five universities. He chose a professorship in Physics at Columbia University. There, in 1939, he confirmed the discovery of the fission process and began striving to attain a nuclear chain reaction.

From 1942 to 1944, Fermi worked at the Metallurgical Laboratory of the University of Chicago. In a makeshift laboratory under Stagg Field Stadium, he designed and built the first nuclear reactor and led the epochal experiment that demonstrated the first self-sustained chain reaction. More than any individual, he was responsible for developing a means for the controlled release of nuclear energy.

Fermi became a U.S. citizen in 1944. From 1944 to 1945, he became Associate Director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. In 1946, he returned to the University of Chicago as a professor at the Institute of Nuclear Studies, which now bears his name--Fermi Institute. He resumed his fundamental research interests in nuclear and elementary particle physics and also, beginning in 1950, served as one of the first members of the General Advisory Committee of the Atomic Energy Commission.

On November 16, 1954, President Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission gave Fermi a special award for his lifetime of accomplishments in physics and, in particular, for the development of atomic energy. Fermi's other research resulted in the Fermi-Dirac particle statistics, the theory of beta-decay, the Thomas-Fermi model of the atom, and a theory of the origin of cosmic rays.

Fermi died on November 28, 1954, and the Enrico Fermi Award was established in 1956 to perpetuate the memory of his brilliance as a scientist and to recognize others of his kind-inspiring others by his example.Enrico Fermi (September 29, 1901 – 29 November 1954) was an Italian-American physicist most noted for his work on beta decay, the development of the first nuclear reactor and for the development of quantum theory. Fermi won the 1938 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Fermi led the construction of the first nuclear pile, which produced the first controlled nuclear chain reaction. He was one of the great leaders of the Manhattan Project.

Fermi is known as the originator of the Fermi paradox in SETI research, when in a discussion of the possibility that intelligent aliens might exist, he famously asked "Where are they?"

Fermions, as well as the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, are named in his honor. In addition, the element fermium and Fermi statistics were named in his honor. The Enrico Fermi US Presidential Award was established in 1956 in memory of Fermi's achievements and excellence as a scientist. The department of the University of Chicago where he used to work is now known as The Enrico Fermi Institute, and the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), was also named in his honor.

Fermi problems, such as the classic "How many piano tuners are there in Chicago?" are named after Fermi's use of such estimation problems to teach students the importance of dimensional analysis, approximation methods, and clear identification of assumptions.

Early years

Fermi was born in Rome. He was inseparable in childhood from his brother Giulio, who was just one year older. In 1915, Giulio died during minor surgery for a throat abscess. Enrico, desolate, threw himself into the study of physics largely as a way of coping with his pain.

A friend of the family, Adolfo Amidei, guided Fermi's study of algebra, trigonometry, analytic geometry, calculus and theoretical mechanics. Amidei also suggested Fermi attend not the University of Rome but to apply to the prestigious "Scuola Normale Superiore" of Pisa, a special university-college for selected gifted students. The examiner at the Scuola Normale thought the 17-year-old Fermi's competition essay worthy of a doctoral exam. The examiner summoned Fermi and predicted he would become a great scientist.

Middle years

In 1918 he attended university at the Pisa Institute where he graduated with a bachelor's degree in 1922. In 1923 Fermi spent 6 months in Göttingen at Max Born's school, but was not happy with the excessively formal theoretical style of the leading school of quantum physics at the time. In 1924 he was in Leiden, Netherlands, to meet Paul Ehrenfest, and here he also met Einstein. Fermi took a professorship in Rome (the first course in theoric physics, created for him by professor Orso Maria Corbino, director of the Institute of Physics). Corbino worked a lot to help Fermi in selecting his team, which soon was joined by notable minds like Edoardo Amaldi, Bruno Pontecorvo, Franco Rasetti, Emilio Segrè. For the theoretic studies only, Ettore Majorana too took part in what was soon nicknamed the Group of "the Boys of via Panisperna" (by the name of the road in which the Institute had its labs - now in the Viminale complex, dicastery of police).

The group went on with its now famous experiments, but in 1933 Rasetti left Italy for Canada and United States, Pontecorvo went to France, Segrè preferred to go teaching in Palermo.

Later years

Fermi remained in Rome until 1938.

In 1938, Fermi won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his "demonstrations of the existence of new radioactive elements produced by neutron irradiation, and for his related discovery of nuclear reactions brought about by slow neutrons."

After Fermi received the prize in Stockholm, he, his wife Laura, and their children emigrated to New York. By this time, the Fascist government in Italy had instituted anti-Semitic laws, and Fermi's wife Laura Capon was Jewish. Soon after his arrival in New York, Fermi began working at Columbia University.

At Columbia, Fermi verified the initial nuclear fission experiment of Hahn and Strassman (with the help of Booth and Dunning). Fermi then began the construction of the first nuclear pile at Columbia.

Fermi recalled the beginning of the project in a speech given in 1954 when he retired as President of the American Physical Society:

"I remember very vividly the first month, January, 1939, that I started working at the Pupin Laboratories because things began happening very fast. In that period, Niels Bohr was on a lecture engagement in Princeton and I remember one afternoon Willis Lamb came back very excited and said that Bohr had leaked out great news. The great news that had leaked out was the discovery of fission and at least the outline of its interpretation. Then, somewhat later that same month, there was a meeting in Washington where the possible importance of the newly discovered phenomenon of fission was first discussed in semi-jocular earnest as a possible source of nuclear power."

After the famous letter signed by Albert Einstein (transcribed by Leó Szilárd) to President Roosevelt in 1939, the Navy awarded Columbia University the first Atomic Energy funding of $6,000. The money was used to develop the first nuclear reactor -- a massive "pile" of graphite bricks filled with uranium which went critical on December 2, 1942. The chain reacting pile was important not only for its help in assessing the properties of fission -- needed for understanding the internal workings of an atomic bomb -- but because it would serve as a pilot plant for the massive reactors which would be created in Hanford, Washington, which would be used to "breed" the plutonium needed for the bombs used at the Trinity test and Nagasaki. Eventually Fermi and Szilard's reactor work were folded in to the Manhattan Project.

In Fermi's 1954 address to the APS he also said, "Well, this brings us to Pearl Harbor. That is the time when I left Columbia University, and after a few months of commuting between Chicago and New York eventually moved to Chicago to keep up the work there, and from then on, with a few notable exceptions, the work at Columbia was concentrated on the isotope separation phase of the atomic energy project, initiated by Booth, Dunning and Urey about 1940."

Fermi was a man of enormous brilliance, mental agility and common sense. He was a very gifted theorist, as his theory of beta decay proves. He was equally gifted in the lab, working very fast and with great insight. Fermi often credited his speed in the lab for having won him the Nobel Prize, saying the discoveries would soon have been made by someone else -- he just got there first.

When he submitted his famous paper on beta decay to the prestigious journal Nature, the journal's editor turned it down because "it contained speculations which were too remote from reality." Thus, Fermi saw the theory published in Italian and in German before it was published in English.

He never forgot this experience of being ahead of his time, and used to tell his protegés: "Never be first; try to be second."Death and afterwards

On November 29, 1954 Fermi died of cancer in Chicago, Illinois and was interred there in the Oak Woods Cemetery. He was 53. As Eugene Wigner wrote: "Ten days before Fermi had passed away he told me, 'I hope it won't take long.' He had reconciled himself perfectly to his fate."Enrico Fermi was born in Rome on 29th September, 1901, the son of Alberto Fermi, a Chief Inspector of the Ministry of Communications, and Ida de Gattis. He attended a local grammar school, and his early aptitude for mathematics and physics was recognized and encouraged by his father's colleagues, among them A. Amidei. In 1918, he won a fellowship of the Scuola Normale Superiore of Pisa. He spent four years at the University of Pisa, gaining his doctor's degree in physics in 1922, with Professor Puccianti.

Soon afterwards, in 1923, he was awarded a scholarship from the Italian Government and spent some months with Professor Max Born in Göttingen. With a Rockefeller Fellowship, in 1924, he moved to Leyden to work with P. Ehrenfest, and later that same year he returned to Italy to occupy for two years (1924-1926) the post of Lecturer in Mathematical Physics and Mechanics at the University of Florence.

In 1926, Fermi discovered the statistical laws, nowadays known as the «Fermi statistics», governing the particles subject to Pauli's exclusion principle (now referred to as «fermions», in contrast with «bosons» which obey the Bose-Einstein statistics).

In 1927, Fermi was elected Professor of Theoretical Physics at the University of Rome (a post which he retained until 1938, when he - immediately after the receipt of the Nobel Prize - emigrated to America, primarily to escape Mussolini's fascist dictatorship).

During the early years of his career in Rome he occupied himself with electrodynamic problems and with theoretical investigations on various spectroscopic phenomena. But a capital turning-point came when he directed his attention from the outer electrons towards the atomic nucleus itself. In 1934, he evolved the ß-decay theory, coalescing previous work on radiation theory with Pauli's idea of the neutrino. Following the discovery by Curie and Joliot of artificial radioactivity (1934), he demonstrated that nuclear transformation occurs in almost every element subjected to neutron bombardment. This work resulted in the discovery of slow neutrons that same year, leading to the discovery of nuclear fission and the production of elements lying beyond what was until then the Periodic Table.

In 1938, Fermi was without doubt the greatest expert on neutrons, and he continued his work on this topic on his arrival in the United States, where he was soon appointed Professor of Physics at Columbia University, N.Y. (1939-I942).

Upon the discovery of fission, by Hahn and Strassmann early in 1939, he immediately saw the possibility of emission of secondary neutrons and of a chain reaction. He proceeded to work with tremendous enthusiasm, and directed a classical series of experiments which ultimately led to the atomic pile and the first controlled nuclear chain reaction. This took place in Chicago on December 2, 1942 - on a squash court situated beneath Chicago's stadium. He subsequently played an important part in solving the problems connected with the development of the first atomic bomb (He was one of the leaders of the team of physicists on the Manhattan Project for the development of nuclear energy and the atomic bomb.)

In 1944, Fermi became American citizen, and at the end of the war (1946) he accepted a professorship at the Institute for Nuclear Studies of the University of Chicago, a position which he held until his untimely death in 1954. There he turned his attention to high-energy physics, and led investigations into the pion-nucleon interaction.

During the last years of his life Fermi occupied himself with the problem of the mysterious origin of cosmic rays, thereby developing a theory, according to which a universal magnetic field - acting as a giant accelerator - would account for the fantastic energies present in the cosmic ray particles.

Professor Fermi was the author of numerous papers both in theoretical and experimental physics. His most important contributions were:

The Nobel Prize for Physics was awarded to Fermi for his work on the artificial radioactivity produced by neutrons, and for nuclear reactions brought about by slow neutrons. The first paper on this subject "Radioattività indotta dal bombardamento di neutroni" was published by him in Ricerca Scientifica, 1934. All the work is collected in the following papers by himself and various collaborators: "Artificial radioactivity produced by neutron bombardment", Proc. Roy. Soc., 1934 and 1935; "On the absorption and diffusion of slow neutrons", Phys. Rev., 1936. The theoretical problems connected with the neutron are discussed by Fermi in the paper "Sul moto dei neutroni lenti", Ricerca Scientfica, 1936.

His Collected Papers are being published by a Committee under the Chairmanship of his friend and former pupil, Professor E. Segrè (Nobel Prize winner 1959, with O. Chamberlain, for the discovery of the antiproton).

Fermi was member of several academies and learned societies in Italy and abroad (he was early in his career, in 1929, chosen among the first 30 members of the Royal Academy of Italy).

As lecturer he was always in great demand (he has also given several courses at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; and Stanford University, Calif.). He was the first recipient of a special award of $50,000 - which now bears his name - for work on the atom.

Professor Fermi married Laura Capon in 1928. They had one son Giulio and one daughter Nella. His favourite pastimes were walking, mountaineering, and winter sports.

He died in Chicago on 28th November, 1954.

The story that his wife Laura tells, is that Enrico Fermi's interest in physics can be traced back to the death of his older brother Giulio when Fermi was just 14. The two boys, just a year apart in age, had been incredibly close. And Giulio's death left Enrico inconsolable. Shortly afterwards he found two old physics textbooks at market that were written by a Jesuit physicist in 1840. Fermi was so intrigued by them, he read them straight through, apparently, not even noticing that they were in Latin. From that point on, physics consumed him.

When Fermi was 17 he applied to the University of Pisa. His entry essay was so advanced that it amazed the examiner who thought it suitable for a graduating doctoral student. In 1926 he became a professor of theoretical physics at the University of Rome. And in the 1930s, he began a series of experiments in which he bombarded a variety of different elements with neutrons. Fermi did not realize until later that he had, in fact, succeeded in splitting the uranium atom. It was for this work that the Nobel Committee awarded him the 1938 prize for physics.

The call from Stockholm was a life-saver for the Fermi family. The night before, a bloody pogrom had taken place in Germany that became known as Kristallnacht. And just a few months earlier, the Italian Fascists had implemented a new anti-Semitic law that claimed: "Jews do not belong to the Italian race." Although Fermi wasn't Jewish, his wife Laura was. The award ceremony gave the family an opportunity to escape Italy and emigrate to America.

At Columbia University in New York, Fermi realized that if neutrons are emitted in the fissioning of uranium then the emitted neutrons might proceed to split other uranium atoms, setting in motion a chain reaction that would release enormous amounts of energy. Together with Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard, Fermi ultimately succeeded in constructing the world's first atomic pile in a squash court under the stands of Stagg Field at the University of Chicago. And on December 2, 1942, it produced the first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. Fermi had succeeded in taking one of the first steps to making an atomic bomb.

One of the participants at that momentous occasion wrote: "Even though we had anticipated the success of the experiment, its accomplishment had a deep impact on us. For some time we had known that we were about to unlock a giant; still we could not escape an eerie feeling when we knew we had actually done it."

After working on the Manhattan Project during the war, Fermi was appointed to the General Advisory Committee, the panel of scientists that advised the Atomic Energy Commission. In October 1949, the GAC met to discuss whether the U.S. should initiate a crash program to build the superbomb. After the meeting, Fermi and Isidor Rabi co-authored a minority addendum to the committee's report. It described the H-bomb in the harshest possible language: "It is clear that such a weapon cannot be justified on any ethical ground... The fact that no limits exist to the destructiveness of this weapon makes its very existence and the knowledge of its construction a danger to humanity as a whole. It is necessarily an evil thing considered in any light."

However, when President Truman ordered a crash program to build the superbomb a couple of months later, Fermi returned temporarily to Los Alamos to help with the calculations. He joined the effort hoping to prove that making a superbomb just wasn't possible.