Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

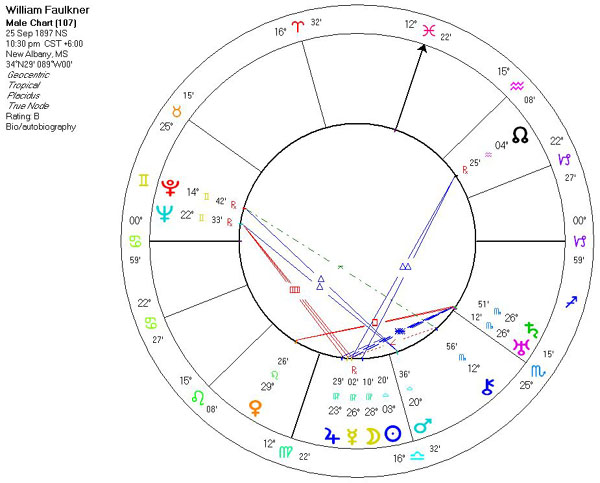

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images Physiognomic Interpretation

A gentleman can live through anything.

A man's moral conscience is the curse he had to accept from the gods in order to gain from them the right to dream.

A mule will labor ten years willingly and patiently for you, for the privilege of kicking you once.

A writer is congenitally unable to tell the truth and that is why we callwhat he writes fiction.

A writer must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid.

All of us failed to match our dreams of perfection. So I rate us on the basis of our splendid failure to do the impossible.

Always dream and shoot higher than you know you can do. Don't bother just to be better than your contemporaries or predecessors. Try to be better than yourself.

An artist is a creature driven by demons. He doesn't know why they choose him and he's usually too busy to wonder why.

Clocks slay time... time is dead as long as it is being clicked off by little wheels; only when the clock stops does time come to life.

Don't bother just to be better than your contemporaries or predecessors. Try to be better than yourself.

Everything goes by the board: honor, pride, decency to get the book written.

Facts and truth really don't have much to do with each other.

Given a choice between grief and nothing, I'd choose grief.

Hollywood is a place where a man can get stabbed in the back while climbing a ladder.

I believe that man will not merely endure. He will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance.

I decline to accept the end of man.

I love Virginians because Virginians are all snobs and I like snobs. A snob has to spend so much time being a snob that he has little time left to meddle with you.

I never know what I think about something until I read what I've written on it.

I'm inclined to think that a military background wouldn't hurt anyone.

If a writer has to rob his mother, he will not hesitate: The "Ode on a Grecian Urn" is worth any number of old ladies.

If I had not existed, someone else would have written me, Hemingway, Dostoevski, all of us.

It is my aim, and every effort bent, that the sum and history of my life, which in the same sentence is my obit and epitaph too, shall be them both: He made the books and he died.

It wasn't until the Nobel Prize that they really thawed out. They couldn't understand my books, but they could understand $30,000.

It's a shame that the only thing a man can do for eight hours a day is work. He can't eat for eight hours; he can't drink for eight hours; he can't make love for eight hours. The only thing a man can do for eight hours is work.

Landlord of a bordello! The company's good and the mornings are quiet, which is the best time to write.

Man performs and engenders so much more than he can or should have to bear. That's how he finds that he can bear anything.

Man will not merely endure; he will prevail.

Maybe the only thing worse than having to give gratitude constantly is having to accept it.

My own experience has been that the tools I need for my trade are paper, tobacco, food, and a little whisky.

Others have done it before me. I can, too.

Our tragedy is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it... the basest of all things is to be afraid.

Read, read, read. Read everything - trash, classics, good and bad, and see how they do it. Just like a carpenter who works as an apprentice and studies the master. Read! You'll absorb it. Then write. If it is good, you'll find out. If it's not, throw it out the window.

The aim of every artist is to arrest motion, which is life, by artificial means and hold it fixed so that a hundred years later, when a stranger looks at it, it moves again since it is life.

The artist doesn't have time to listen to the critics. The ones who want to be writers read the reviews, the ones who want to write don't have the time to read reviews.

The artist is of no importance. Only what he creates is important, since there is nothing new to be said. Shakespeare, Balzac, Homer have all written about the same things, and if they had lived one thousand or two thousand years longer, the publishers wouldn't have needed anyone since.

The end of wisdom is to dream high enough to lose the dream in the seeking of it.

The last sound on the worthless earth will be two human beings trying to launch a homemade spaceship and already quarreling about where they are going next.

The man who removes a mountain begins by carrying away small stones.

The past is not dead. In fact, it's not even past.

The salvation of the world is in man's suffering.

The tools I need for my work are paper, tobacco, food, and a little whiskey.

There is something about jumping a horse over a fence, something that makes you feel good. Perhaps it's the risk, the gamble. In any event it's a thing I need.

This is a free country. Folks have a right to send me letters, and I have a right not to read them.

To live anywhere in the world today and be against equality because of race or color is like living in Alaska and being against snow.

Well, between Scotch and nothin', I suppose I'd take Scotch. It's the nearest thing to good moonshine I can find.

Why that's a hundred miles away. That's a long way to go just to eat.

WILLIAM CUTHBERT FAULKNER, original surname FALKNER (b. Sept. 25, 1897, New Albany, Miss., U.S.--d. July 6, 1962, Byhalia, Miss.), American novelist and short-story writer who was awarded the 1949 Nobel Prize for Literature.

Youth and early writings.

As the eldest of the four sons of Murry Cuthbert and Maud Butler Falkner, William Faulkner (as he later spelled his name) was well aware of his family background and especially of his great-grandfather, Colonel William Clark Falkner, a colourful if violent figure who fought gallantly during the Civil War, built a local railway, and published a popular romantic novel called The White Rose of Memphis. Born in New Albany, Miss., Faulkner soon moved with his parents to nearby Ripley and then to the town of Oxford, the seat of Lafayette county, where his father later became business manager of the University of Mississippi. In Oxford he experienced the characteristic open-air upbringing of a Southern white youth of middle-class parents: he had a pony to ride and was introduced to guns and hunting. A reluctant student, he left high school without graduating but devoted himself to "undirected reading," first in isolation and later under the guidance of Phil Stone, a family friend who combined study and practice of the law with lively literary interests and was a constant source of current books and magazines.

In July 1918, impelled by dreams of martial glory and by despair at a broken love affair, Faulkner joined the British Royal Air Force (RAF) as a cadet pilot under training in Canada, although the November 1918 armistice intervened before he could finish ground school, let alone fly or reach Europe. After returning home, he enrolled for a few university courses, published poems and drawings in campus newspapers, and acted out a self-dramatizing role as a poet who had seen wartime service. After working in a New York bookstore for three months in the fall of 1921, he returned to Oxford and ran the university post office there with notorious laxness until forced to resign. In 1924 Stone's financial assistance enabled him to publish The Marble Faun, a pastoral verse-sequence in rhymed octosyllabic couplets. There were also early short stories, but Faulkner's first sustained attempt to write fiction occurred during a six-month visit to New Orleans--then a significant literary centre--that began in January 1925 and ended in early July with his departure for a five-month tour of Europe, including several weeks in Paris.

His first novel, Soldiers' Pay (1926), given a Southern though not a Mississippian setting, was an impressive achievement, stylistically ambitious and strongly evocative of the sense of alienation experienced by soldiers returning from World War I to a civilian world of which they seemed no longer a part. A second novel, Mosquitoes (1927), launched a satirical attack on the New Orleans literary scene, including identifiable individuals, and can perhaps best be read as a declaration of artistic independence. Back in Oxford--with occasional visits to Pascagoula on the Gulf Coast--Faulkner again worked at a series of temporary jobs but was chiefly concerned with proving himself as a professional writer. None of his short stories was accepted, however, and he was especially shaken by his difficulty in finding a publisher for Flags in the Dust (published posthumously, 1973), a long, leisurely novel, drawing extensively on local observation and his own family history, that he had confidently counted upon to establish his reputation and career. When the novel eventually did appear, severely truncated, as Sartoris in 1929, it created in print for the first time that densely imagined world of Jefferson and Yoknapatawpha County--based partly on Ripley but chiefly on Oxford and Lafayette county and characterized by frequent recurrences of the same characters, places, and themes--which Faulkner was to use as the setting for so many subsequent novels and stories.

The major novels.

Faulkner had meanwhile "written [his] guts" into the more technically sophisticated The Sound and the Fury, believing that he was fated to remain permanently unpublished and need therefore make no concessions to the cautious commercialism of the literary marketplace. The novel did find a publisher, despite the difficulties it posed for its readers, and from the moment of its appearance in October 1929 Faulkner drove confidently forward as a writer, engaging always with new themes, new areas of experience, and, above all, new technical challenges. Crucial to his extraordinary early productivity was the decision to shun the talk, infighting, and publicity of literary centres and live instead in what was then the small-town remoteness of Oxford, where he was already at home and could devote himself, in near isolation, to actual writing. In 1929 he married Estelle Oldham--whose previous marriage, now terminated, had helped drive him into the RAF in 1918. One year later he bought Rowan Oak, a handsome but run-down pre-Civil War house on the outskirts of Oxford, restoration work on the house becoming, along with hunting, an important diversion in the years ahead. A daughter, Jill, was born to the couple in 1933, and although their marriage was otherwise troubled, Faulkner remained working at home throughout the 1930s and '40s, except when financial need forced him to accept the Hollywood screenwriting assignments he deplored but very competently fulfilled.

Oxford provided Faulkner with intimate access to a deeply conservative rural world, conscious of its past and remote from the urban-industrial mainstream, in terms of which he could work out the moral as well as narrative patterns of his work. His fictional methods, however, were the reverse of conservative. He knew the work not only of Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert, Charles Dickens, and Herman Melville but also of Joseph Conrad, James Joyce, Sherwood Anderson, and other recent figures on both sides of the Atlantic, and in The Sound and the Fury (1929), his first major novel, he combined a Yoknapatawpha setting with radical technical experimentation. In successive "stream-of-consciousness" monologues the three brothers of Candace (Caddy) Compson--Benjy the idiot, Quentin the disturbed Harvard undergraduate, and Jason the embittered local businessman--expose their differing obsessions with their sister and their loveless relationships with their parents. A fourth section, narrated as if authorially, provides new perspectives on some of the central characters, including Dilsey, the Compsons' black servant, and moves toward a powerful yet essentially unresolved conclusion. Faulkner's next novel, the brilliant tragicomedy called As I Lay Dying (1930), is centred upon the conflicts within the "poor white" Bundren family as it makes its slow and difficult way to Jefferson to bury its matriarch's malodorously decaying corpse. Entirely narrated by the various Bundrens and people encountered on their journey, it is the most systematically multi-voiced of Faulkner's novels and marks the culmination of his early post-Joycean experimentalism.

Although the psychological intensity and technical innovation of these two novels were scarcely calculated to ensure a large contemporary readership, Faulkner's name was beginning to be known in the early 1930s, and he was able to place short stories even in such popular--and well-paying--magazines as Collier's and Saturday Evening Post. Greater, if more equivocal, prominence came with the financially successful publication of Sanctuary, a novel about the brutal rape of a Southern college student and its generally violent, sometimes comic, consequences. A serious work, despite Faulkner's unfortunate declaration that it was written merely to make money, Sanctuary was actually completed prior to As I Lay Dying and published, in February 1931, only after Faulkner had gone to the trouble and expense of restructuring and partly rewriting it--though without moderating the violence--at proof stage. Despite the demands of film work and short stories (of which a first collection appeared in 1931 and a second in 1934), and even the preparation of a volume of poems (published in 1933 as A Green Bough), Faulkner produced in 1932 another long and powerful novel. Complexly structured and involving several major characters, Light in August revolves primarily upon the contrasted careers of Lena Grove, a pregnant young countrywoman serenely in pursuit of her biological destiny, and Joe Christmas, a dark-complexioned orphan uncertain as to his racial origins, whose life becomes a desperate and often violent search for a sense of personal identity, a secure location on one side or the other of the tragic dividing line of colour.

Made temporarily affluent by Sanctuary and Hollywood, Faulkner took up flying in the early 1930s, bought a Waco cabin aircraft, and flew it in February 1934 to the dedication of Shushan Airport in New Orleans, gathering there much of the material for Pylon, the novel about racing and barnstorming pilots that he published in 1935. Having given the Waco to his youngest brother, Dean, and encouraged him to become a professional pilot, Faulkner was both grief- and guilt-stricken when Dean crashed and died in the plane later in 1935; when Dean's daughter was born in 1936 he took responsibility for her education. The experience perhaps contributed to the emotional intensity of the novel on which he was then working. In Absalom, Absalom! (1936) Thomas Sutpen arrives in Jefferson from "nowhere," ruthlessly carves a large plantation out of the Mississippi wilderness, fights valiantly in the Civil War in defense of his adopted society, but is ultimately destroyed by his inhumanity toward those whom he has used and cast aside in the obsessive pursuit of his grandiose dynastic "design." By refusing to acknowledge his first, partly black, son, Charles Bon, Sutpen also loses his second son, Henry, who goes into hiding after killing Bon (whom he loves) in the name of their sister's honour. Because this profoundly Southern story is constructed--speculatively, conflictingly, and inconclusively--by a series of narrators with sharply divergent self-interested perspectives, Absalom, Absalom! is often seen, in its infinite open-endedness, as Faulkner's supreme "modernist" fiction, focused above all on the processes of its own telling.

Later life and works.

The novel The Wild Palms (1939) was again technically adventurous, with two distinct yet thematically counterpointed narratives alternating, chapter by chapter, throughout. But Faulkner was beginning to return to the Yoknapatawpha County material he had first imagined in the 1920s and subsequently exploited in short-story form. The Unvanquished (1938) was relatively conventional, but The Hamlet (1940), the first volume of the long-uncompleted "Snopes" trilogy, emerged as a work of extraordinary stylistic richness. Its episodic structure is underpinned by recurrent thematic patterns and by the wryly humorous presence of V.K. Ratliff--an itinerant sewing-machine agent--and his unavailing opposition to the increasing power and prosperity of the supremely manipulative Flem Snopes and his numerous "poor white" relatives. In 1942 appeared Go Down, Moses, yet another major work, in which an intense exploration of the linked themes of racial, sexual, and environmental exploitation is conducted largely in terms of the complex interactions between the "white" and "black" branches of the plantation-owning McCaslin family, especially as represented by Isaac McCaslin on the one hand and Lucas Beauchamp on the other.

For various reasons--the constraints on wartime publishing, financial pressures to take on more scriptwriting, difficulties with the work later published as A Fable--Faulkner did not produce another novel until Intruder in the Dust (1948), in which Lucas Beauchamp, reappearing from Go Down, Moses, is proved innocent of murder, and thus saved from lynching, only by the persistent efforts of a young white boy. Racial issues were again confronted, but in the somewhat ambiguous terms that were to mark Faulkner's later public statements on race: while deeply sympathetic to the oppression suffered by blacks in the Southern states, he nevertheless felt that such wrongs should be righted by the South itself, free of Northern intervention.

Faulkner's American reputation--which had always lagged well behind his reputation in Europe--was boosted by The Portable Faulkner (1946), an anthology skillfully edited by Malcolm Cowley in accordance with the arresting if questionable thesis that Faulkner was deliberately constructing an historically based "legend" of the South. Faulkner's Collected Stories (1950), impressive in both quantity and quality, was also well received, and later in 1950 the award of the Nobel Prize for Literature catapulted the author instantly to the peak of world fame and enabled him to affirm, in a famous acceptance speech, his belief in the survival of the human race, even in an atomic age, and in the importance of the artist to that survival.

The Nobel Prize had a major impact on Faulkner's private life. Confident now of his reputation and future sales, he became less consistently "driven" as a writer than in earlier years and allowed himself more personal freedom, drinking heavily at times and indulging in a number of extramarital affairs--his opportunities in these directions being considerably enhanced by a final screenwriting assignment in Egypt in 1954 and several overseas trips (most notably to Japan in 1955) undertaken on behalf of the U.S. State Department. He took his "ambassadorial" duties seriously, speaking frequently in public and to interviewers, and also became politically active at home, taking positions on major racial issues in the vain hope of finding middle ground between entrenched Southern conservatives and interventionist Northern liberals. Local Oxford opinion proving hostile to such views, Faulkner in 1957 and 1958 readily accepted semester-long appointments as writer-in-residence at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. Attracted to the town by the presence of his daughter and her children as well as by its opportunities for horse-riding and fox-hunting, Faulkner bought a house there in 1959, though continuing to spend time at Rowan Oak.

The quality of Faulkner's writing is often said to have declined in the wake of the Nobel Prize. But the central sections of Requiem for a Nun (1951) are challengingly set out in dramatic form, and A Fable (1954), a long, densely written, and complexly structured novel about World War I, demands attention as the work in which Faulkner made by far his greatest investment of time, effort, and authorial commitment. In The Town (1957) and The Mansion (1959) Faulkner not only brought the "Snopes" trilogy to its conclusion, carrying his Yoknapatawpha narrative to beyond the end of World War II, but subtly varied the management of narrative point of view. Finally, in June 1962 Faulkner published yet another distinctive novel, the genial, nostalgic comedy of male maturation he called The Reivers and appropriately subtitled "A Reminiscence." A month later he was dead, of a heart attack, at the age of 64, his health undermined by his drinking and by too many falls from horses too big for him.

Assessment.

By the time of his death Faulkner had clearly emerged not just as the major American novelist of his generation but as one of the greatest writers of the 20th century, unmatched for his extraordinary structural and stylistic resourcefulness, for the range and depth of his characterization and social notation, and for his persistence and success in exploring fundamental human issues in intensely localized terms. Some critics, early and late, have found his work extravagantly rhetorical and unduly violent, and there have been strong objections, especially late in the 20th century, to the perceived insensitivity of his portrayals of women and black Americans. His reputation, grounded in the sheer scale and scope of his achievement, seems nonetheless secure, and he remains a profoundly influential presence for novelists writing in the United States, South America, and, indeed, throughout the world.

William Falkner wrote works of psychological drama and emotional depth, typically with long serpentine prose and high, meticulously-chosen diction. Like most prolific authors, he suffered the envy and scorn of others, and was considered to be the stylistic rival to Ernest Hemingway (his long sentences contrasted to Hemingway's short, 'minimalist' style). He is perhaps also considered to be the only true American Modernist prose fiction writer of the 1930s, following in experimental tradition European writers such as James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, and Marcel Proust, and known for using groundbreaking literary devices such as stream of consciousness, multiple narrations or points of view, and time-shifts within narrative.

Faulkner was born William Falkner (no "U") in New Albany, Mississippi, and raised in and heavily influenced by that state, as well as the general ambience of the South. Mississippi marked his sense of humor, his sense of the tragic position of Blacks and Whites, his keen characterization of usual Southern characters and his timeless themes, one of them being that fiercely intelligent people dwelled behind the facade of good old boys and simpletons. An early editor misspelled Falkner's name as "Faulkner", and the author decided to keep the spelling.

Faulkner's most celebrated novels include The Sound and the Fury (1929), As I Lay Dying (1930), Light in August (1932), The Unvanquished (1938), and Absalom, Absalom (1936), which are usually considered masterpieces. Faulkner was a prolific writer of short stories: his first short story collection, These 13 (1931), includes many of his most acclaimed (and most frequently anthologized) stories, including "A Rose for Emily," "Red Leaves," "That Evening Sun," and "Dry September." During the 1930s, in an effort to make money, Faulkner crafted a sensationalist "pulp" novel entitled Sanctuary (first published in 1931). Its themes of evil and corruption (bearing Southern Gothic tones), resonate to this day. A sequel to the book, Requiem for a Nun, is the only play that he has published. It involves an introduction that is actually one sentence that spans for a couple pages. He received a Pulitzer Prize for A Fable, and won a National Book Award (posthumously) for his Collected Stories.

Faulkner was also an acclaimed writer of mysteries, publishing a collection of crime fiction, Knight's Gambit, that featured Gavin Stevens, an attorney, wise to the ways of folk living in Yoknapatawpha County. He set many of his short stories and novels in his fictional Yoknapatawpha County, based on--and nearly identical to in terms of geography--Lafayette County, of which his hometown of Oxford, Mississippi is the county seat; Yoknapatawpha was his very own "postage stamp" and it is considered to be one of the most monumetal fictional creations in the history of literature.

In his later years Faulkner moved to Hollywood to be a screenwriter (producing scripts for Raymond Chandler's The Big Sleep and Ernest Hemingway's To Have and Have Not--both directed by Howard Hawks). Faulkner started an affair with a secretary for Hawks, Meta Carpenter.

Faulkner was known rather infamously for his drinking problem as well, and throughout his life was known to be an alcoholic.

He was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature in 1949. He drank shortly before he had to sail to Stockholm to receive the distinguished prize. Once there, he delivered one of the greatest speeches any literature recipient had ever given. In it, he remarked "I decline to accept the end of man...Man will not only endure, but prevail..." Both events were fully in character. Faulkner donated his Nobel winnings, "to establish a fund to support and encourage new fiction writers", eventually resulting in the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction.

Faulkner served as Writer-In-Residence at the University of Virginia from 1957 until his death in 1962.

William Faulkner (1897-1962), who came from an old southern family, grew up in Oxford, Mississippi. He joined the Canadian, and later the British, Royal Air Force during the First World War, studied for a while at the University of Mississippi, and temporarily worked for a New York bookstore and a New Orleans newspaper. Except for some trips to Europe and Asia, and a few brief stays in Hollywood as a scriptwriter, he worked on his novels and short stories on a farm in Oxford.

In an attempt to create a saga of his own, Faulkner has invented a host of characters typical of the historical growth and subsequent decadence of the South. The human drama in Faulkner's novels is then built on the model of the actual, historical drama extending over almost a century and a half Each story and each novel contributes to the construction of a whole, which is the imaginary Yoknapatawpha County and its inhabitants. Their theme is the decay of the old South, as represented by the Sartoris and Compson families, and the emergence of ruthless and brash newcomers, the Snopeses. Theme and technique - the distortion of time through the use of the inner monologue are fused particularly successfully in The Sound and the Fury (1929), the downfall of the Compson family seen through the minds of several characters. The novel Sanctuary (1931) is about the degeneration of Temple Drake, a young girl from a distinguished southern family. Its sequel, Requiem For A Nun (1951), written partly as a drama, centered on the courtroom trial of a Negro woman who had once been a party to Temple Drake's debauchery. In Light in August (1932), prejudice is shown to be most destructive when it is internalized, as in Joe Christmas, who believes, though there is no proof of it, that one of his parents was a Negro. The theme of racial prejudice is brought up again in Absalom, Absalom! (1936), in which a young man is rejected by his father and brother because of his mixed blood. Faulkner's most outspoken moral evaluation of the relationship and the problems between Negroes and whites is to be found in Intruder In the Dust (1948).

In 1940, Faulkner published the first volume of the Snopes trilogy, The Hamlet, to be followed by two volumes, The Town (1957) and The Mansion (1959), all of them tracing the rise of the insidious Snopes family to positions of power and wealth in the community. The reivers, his last - and most humorous - work, with great many similarities to Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn, appeared in 1962, the year of Faulkner's death.

From Nobel Lectures, Literature 1901-1967, Editor Horst Frenz, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1969

William Faulkner died on July 6, 1962.