Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

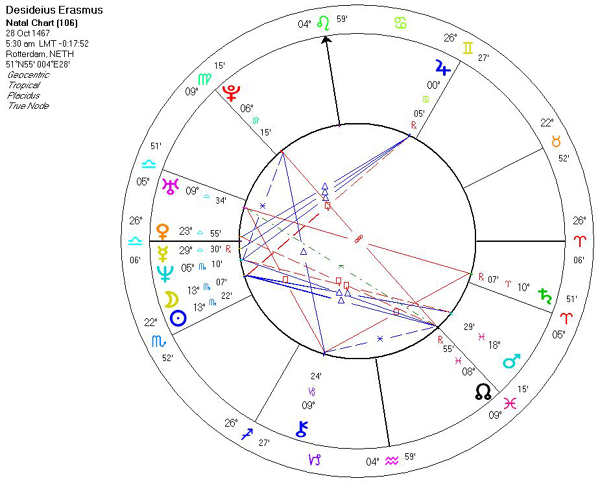

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

A nail is driven out by another nail. Habit is overcome by habit.

By a Carpenter mankind was made, and only by that Carpenter can mankind be remade.

Concealed talent brings no reputation.

Don't give your advice before you are called upon.

(Venus in Libra)Fools are without number.

Give light, and the darkness will disappear of itself.

Great abundance of riches cannot be gathered and kept by any man without sin.

(Scorpio Sun & Moon)Great eagerness in the pursuit of wealth, pleasure, or honor, cannot exist without sin.

He who allows oppression shares the crime.

(Mars in Pisces)Heaven grant that the burden you carry may have as easy an exit as it had an entrance.

If you keep thinking about what you want to do or what you hope will happen, you don't do it, and it won't happen.

In the kingdom of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.

It is the chiefest point of happiness that a man is willing to be what he is.

It is wisdom in prosperity, when all is as thou wouldn't have it, to fear and suspect the worst.

Jupiter, not wanting man's life to be wholly gloomy and grim, has bestowed far more passion than reason -you could reckon the ration as twenty-four to one. Moreover, he confined reason to a cramped corner of the head and left all the rest of the body to the passions.

(Jupiter in Cancer in 9th house. Scorpio Sun & Moon.)Luther was guilty of two great crimes - he struck the Pope in his crown, and the monks in their belly.

Man's mind is so formed that it is far more susceptible to falsehood than to truth.

Nature, more of a stepmother than a mother in several ways, has sown a seed of evil in the hearts of mortals, especially in the more thoughtful men, which makes them dissatisfied with their own lot and envious of another’s.

No one respects a talent that is concealed.

Nothing is as peevish and pedantic as men's judgments of one another.

Prevention is better than cure.

Reflection is a flower of the mind, giving out wholesome fragrance; but revelry is the same flower, when rank and running to seed.

The desire to write grows with writing.

(Mercury in Libra conjunct Ascendant.)The entire world is my temple, and a very fine one too, if I'm not mistaken, and I'll never lack priests to serve it as long as there are men.

The most disadvantageous peace is better than the most just war.

(Libra Ascendant)There are some people who live in a dream world, and there are some who face reality; and then there are those who turn one into the other.

This type of man who is devoted to the study of wisdom is always most unlucky in everything, and particularly when it comes to procreating children; I imagine this is because Nature wants to ensure that the evils of wisdom shall not spread further throughout mankind.

Time takes away the grief of men.

War is delightful to those who have had no experience of it.

What difference is there, do you think, between those in Plato's cave who can only marvel at the shadows and iimages of various objects, provided they are content and don't know what they miss, and the philosopher who has emerged from the cave and sees the real things?

What is popularly called fame is nothing but an empty name and a legacy from paganism.

When I get a little money I buy books; and if any is left I buy food and clothes.

(Jupiter in 9th house.)Women, can't live with them, can't live without them.

You'll see certain Pythagorean whose belief in communism of property goes to such lengths that they pick up anything lying about unguarded, and make off with it without a qualm of conscience as if it had come to them by law.

Your library is your paradise.

(Jupiter in 9th house)I doubt if a single individual could be found from the whole of mankind free from some form of insanity. The only difference is one of degree. A man who sees a gourd and takes it for his wife is called insane because this happens to very few people.

“By burning Luther's books you may rid your bookshelves of him, but you will not rid men's minds of him”

“A good prince will tax as lightly as possible those commodities which are used by the poorest members of society: grain, bread, beer, wine, clothing, and all other staples without which human life could not exist”

(Mars in Pisces)“To know nothing is the happiest life”

Desiderius Erasmus in 1523Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (also Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam) (October 27, probably 1466 – July 12, 1536) was a Dutch humanist and theologian.

Erasmus was a classical scholar who wrote in a "pure" Latin style. Although he remained a Roman Catholic throughout his lifetime, he harshly criticised what he considered the excesses of the Roman Catholic Church and even turned down a Cardinalship when it was offered to him.

He prepared new Latin and Greek editions of the New Testament and wrote The Praise of Folly, Handbook of a Christian Knight and On Civility in Children.

Early life

Erasmus was born with the name Gerrit Gerritszoon (Dutch for Gerhard Gerhardson) in or about 1466, probably in Rotterdam. Although associated closely with this city, he lived there for only four years, never to return. Information on his family and early life comes mainly from vague references in his writings. He was almost certainly illegitimate. His father later became a priest named Roger Gerard. Little is known of his mother other than her name was Margaret and she was the daughter of a physician. Despite being illegitimate, Erasmus was cared for by his parents until their early deaths from the plague in 1483 and was then given the best education available to a young man of his day, in a series of monastic or semi-monastic schools. In 1487 Erasmus became deeply attached to a young man, Servatius Rogerus, whom he called "half my soul", writing, "I have wooed you both unhappily and relentlessly."[1]Ordination and monastic experience

In 1492, he was ordained to the Catholic priesthood and took Augustinian monastic vows at about the age of 25, but he never seems to have actively worked as a monastic priest, and monasticism was one of the chief objects of his attack in his lifelong assault upon Church excesses. Soon after his priestly ordination, he got his chance to leave the monastery when offered the post of secretary to the Bishop of Cambray, Henry of Bergen, on account of his great skill in Latin and his reputation as a man of letters. He was given a temporary dispensation due to his poor health, dislike of monks and love of humanistic studies. Pope Leo X later made the dispensation permanent.E-ducation and scholarship

In 1495, with the bishop's consent and stipend, he went on to study at the University of Paris, in the Collège de Montaigu, a centre of reforming zeal, under the direction of the ascetic Jan Standonck, of whose rigours Erasmus complained. The University was then the chief seat of scholastic learning, but already under the influence of the revived classical culture of Italy. The chief centers of his activity were Paris, Leuven (Louvain), England, and Basel; yet he never belonged firmly in any one of these places. His time in England was fruitful in the making of lifelong friendships with the leaders of English thought in the stirring days of King Henry VIII: John Colet, Thomas More, John Fisher, Thomas Linacre and William Grocyn. At the University of Cambridge, he was the Lady Margaret's Professor of Divinity and had the option of spending the rest of his life as an English professor. He stayed at Queens' College, Cambridge, and may have been an alumnus.Erasmus preferred to live the life of an independent scholar and made a conscious effort to avoid any actions or formal ties that might inhibit his freedom of intellect and literary expression. Throughout his life, he was offered many positions of honor and profit throughout the academic world but declined them all, preferring the uncertain but sufficient rewards of independent literary activity. From 1506 to 1509, he was in Italy and spent part of the time at the publishing house of Aldus Manutius in Venice, but, apart from this, he had a less active association with Italian scholars than might have been expected.

His residence at Leuven exposed Erasmus to much petty criticism from those hostile to the principles of literary and religious progress to which he was devoting his life. Feeling that this lack of sympathy was actually persecution, he sought refuge in Basel, where under the shelter of Swiss hospitality he could express himself freely and where he was surrounded by devoted friends. Here he was associated for many years with the great publisher Froben, and to him came the multitude of his admirers from all quarters of Europe.

Erasmus's literary productivity began comparatively late in his life. Only when he had mastered Latin did he begin to express himself on major contemporary themes in literature and religion. His revolt against the forms of church life did not result from doubts about the truth of the traditional doctrine nor from any hostility to the organization of the Church itself. Rather, he felt called upon to use his learning in a purification of the doctrine and in a liberalizing of the institutions of Christianity. As a scholar, he tried to free the methods of scholarship from the rigidity and formalism of medieval traditions, but he was not satisfied with this. He saw himself as a preacher of righteousness. It was this lifelong conviction that guided Erasmus as he regenerated Europe through sound criticism applied frankly and without fear to the Catholic Church. This conviction gives unity and consistency to a life which might otherwise seem full of contradictions. Erasmus held himself aloof from all entangling obligations, yet he was, in a singularly true sense, the center of the literary movement of his time. He corresponded with more than five hundred men of the highest importance in the world of politics and of thought, and his advice on all kinds of subjects was eagerly sought, if not always followed.

Publication of the Greek New Testament

The first New Testament printed in Greek was part of the Polyglot Bible. This portion was printed in 1514, but publication was delayed until 1522 by waiting for the Old Testament portion, and the sanction of Pope Leo X.[2] While in England in 1515, Erasmus became aware of the Polyglot project and began a search for available manuscripts of the Greek New Testament with the goal of meeting the demand for a printed edition before the Polyglot Bible could be finished. Erasmus's rushed effort was published by Froben of Basel in 1516 and thence became the first published Greek New Testament, the Novum Instrumentum omne, diligenter ab Erasmo Rot. Recognitum et Emendatum. This critical edition included a Latin translation and annotations. Erasmus used several Greek manuscript sources because he did not have access to a single complete manuscript. Because of its hasty production, the 1516 edition contains numerous typographical errors.In the 2nd (1519) edition the more familiar term Testamentum was used instead of Instrumentum. This edition was used by Martin Luther in making his German translation. Together, the first and second editions sold 3,300 copies. The 1st- and 2nd-edition texts did not include the passage (1 John 5:7–8) that has become known as the Comma Johanneum. These verses appear to be a basis of the Apostles' and Nicene Creeds. Erasmus had been unable to find those verses in any Greek manuscript, but one was supplied to him during production of the 3rd edition. That manuscript is now thought to be a 1520 creation from the Latin Vulgate, which likely got the verses from a 5th-century marginal gloss in a Latin copy of I John. The Roman Catholic Church decreed that the Comma Johanneum was open to dispute (June 2, 1927), and it is rarely included in modern scholarly translations.

The 3rd edition of 1522 was the basis for the 1550 Robert Stephanus edition used by the translators of the Geneva Bible and King James Version of the Bible. Erasmus published a definitive 4th edition in 1527 containing parallel columns of Greek, Latin Vulgate and Erasmus's Latin texts. He used the now available Polyglot Bible to improve this version. In 1535 Erasmus published the 5th (and final) edition which dropped the Latin Vulgate column but was otherwise similar to the 4th edition. Subsequent versions of Erasmus's Greek New Testament became known as the Textus Receptus.

Erasmus dedicated his work to Pope Leo X as a patron of learning and regarded this work as his chief service to the cause of Christianity. Immediately afterward, he began the publication of his Paraphrases of the New Testament, a popular presentation of the contents of the several books. These, like all of his writings, were published in Latin but were quickly translated into other languages, with his encouragement.

Erasmus, Luther, and the beginnings of Protestantism

[edit] Tries to be impartial in dispute

Martin Luther's movement began in the year following the publication of the New Testament and tested Erasmus's character. The issue between European society and the Roman Church had become so clear that few could escape the summons to join the debate. Erasmus, at the height of his literary fame, was inevitably called upon to take sides, but partisanship was foreign to his nature and his habits. In all his criticism of clerical follies and abuses, he had always protested that he was not attacking church institutions themselves and had no enmity toward churchmen. The world had laughed at his satire, but few had interfered with his activities. He believed that his work so far had commended itself to the best minds and also to the dominant powers in the religious world.

[edit] Disagreement with Luther

Erasmus was sympathetic with the main points in the Lutheran criticism of the Church. He had great respect for Martin Luther, and Luther always spoke with admiration of Erasmus's superior learning. Luther hoped for his cooperation in a work which seemed only the natural outcome of his own. In their early correspondence, Luther expressed boundless admiration for all Erasmus had done in the cause of a sound and reasonable Christianity and urged him to join the Lutheran party. Erasmus declined to commit himself, arguing that to do so would endanger his position as a leader in the movement for pure scholarship which he regarded as his purpose in life. Only as an independent scholar could he hope to influence the reform of religion. When Erasmus hesitated to support him, the straightforward Luther felt that Erasmus was avoiding the responsibility due either to cowardice or a lack of purpose. Erasmus, however, dreaded any change in doctrine and believed that there was room within existing formulas for the kind of reform he valued most.

[edit] Freedom of the will

Twice in the course of the great discussion, he allowed himself to enter the field of doctrinal controversy, a field foreign to both his nature and his previous practice. One of the topics he dealt with was the freedom of the will, a crucial point. In his De libero arbitrio diatribe sive collatio (1524), he lampoons the Lutheran view on free will. He lays down both sides of the argument impartially. The "Diatribe" did not encourage any definite action; this was its merit to the Erasmians and its fault in the eyes of the Lutherans. In response, Luther wrote his De servo arbitrio (On the Bondage of the Will) (1525), which viciously attacks the "Diatribe" and Erasmus himself, going so far as to claim that Erasmus was not a Christian.As the popular response to Luther gathered momentum, the social disorders, which Erasmus dreaded and Luther deemed unavoidable, began to appear, including the Peasants' War, the Anabaptist disturbances in Germany and in the Low Countries, iconoclasm and the radicalization of peasants across Europe. If these were the outcomes of reform, he was thankful that he had kept out of it. Yet he was ever more bitterly accused of having started the whole "tragedy" (as the Roman Catholics dubbed Protestantism).

When the city of Basel was definitely and officially "reformed" in 1529, Erasmus gave up his residence there and settled in the imperial town of Freiburg im Breisgau.

Erasmus by Holbein

[edit] The sacraments

The test question was the doctrine of the sacraments, and the crux of this question was the observance of the Eucharist. In 1530, Erasmus published a new edition of the orthodox treatise of Algerus against the heretic Berengar of Tours in the 11th century. He added a dedication, affirming his belief in the reality of the Body of Christ after consecration in the Eucharist. The anti-sacramentarians, headed by Œcolampadius of Basel, were, as Erasmus says, quoting him as holding views similar to their own in order to try to claim him for their schismatic movement.

[edit] Writings

Erasmus wrote both on ecclesiastic subjects and those of general human interest. He seems to have regarded the latter as trifling, a leisure activity.He is credited with coining the adage, "In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king." He formed a collection of adages, commonly called Adagia.

His more serious writings begin early with the Enchiridion militis Christiani, the "Handbook of the Christian Soldier" (1503) (translated into English a few years later by the young William Tyndale). In this short work, Erasmus outlines the views of the normal Christian life, which he was to spend the rest of his days in elaborating. The chief evil of the day, he says, is formalism, going through the motions of tradition without understanding their basis in the teachings of Christ. Forms can teach the soul how to worship God, or they may hide or quench the spirit. In his examination of the dangers of formalism, Erasmus discusses monasticism, saint worship, war, the spirit of class and the foibles of "society", but the Enchiridion is more like a sermon than a satire.

Erasmus's best-known work was The Praise of Folly, (Latin: Moriae encomium or sometimes Laus stultitiae), a satirical attack on the traditions of the Catholic Church and popular superstitions, written in 1509, published in 1511 and dedicated to his friend, Sir Thomas More.

The Institutio principis Christiani (Basel, 1516) (Education of a Christian Prince) was written as advice to the young king Charles of Spain, later Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Erasmus applies the general principles of honor and sincerity to the special functions of the Prince, whom he represents throughout as the servant of the people. The Education of a Christian Prince was published in 1516, 26 years before Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince. A comparison between the two is worth noting. Machiavelli stated that, to maintain control by political force, it is safer for a prince to be feared than loved. Erasmus, on the other hand, preferred for the prince to be loved and suggested that the prince needed a well-rounded education in order to govern justly and benevolently and avoid becoming a source of oppression.

As a result of his reformatory activities, Erasmus found himself at odds with both the great parties. His last years were embittered by controversies with men toward whom he was sympathetic. Notable among these was Ulrich von Hutten, a brilliant but erratic genius, who had thrown himself into the Lutheran cause and had declared that Erasmus, if he had a spark of honesty, would do the same. In his reply, Spongia adversus aspergines Hutteni (1523), Erasmus displays his skill in semantics. He accuses Hutten of having misinterpreted his utterances about reform and reiterates his determination never to break with the Church.

The most important work of this last period is the Ecclesiastes or "Gospel Preacher" (Basel, 1535), in which he comments on the function of preaching.

[edit] Legacy

The extraordinary popularity of his books, however, has been shown in the number of editions and translations that have appeared since the 16th century, and in the undiminished interest excited by his elusive but fascinating personality. Ten columns of the catalogue of the British Library are taken up with the bare enumeration of the works and their subsequent reprints. The greatest names of the classical and patristic world are among those translated, edited or annotated by Erasmus, including Saint Ambrose, Aristotle, Saint Augustine, Saint Basil, Saint John Chrysostom, Cicero and Saint Jerome.Today in his home town of Rotterdam, the University has been named in his honor. However, Rotterdam has ignored the life of his most famous citizen for a long time. Research in 2003 showed that most Rotterdammers believe Erasmus was the designer of the "Erasmusbridge" in Rotterdam. This shocking information led to the founding of the Erasmushuis (Erasmushouse), a house dedicated to celebrate the legacy of Erasmus. Nowadays in Rotterdam, three famous moments in the life of Erasmus are celebrated annually. On April 1, the city celebrates the release of "Lof der Zotheid" (Erasmus' most famous book). On October 28, the birthday of Erasmus is celebrated. And, in the summer, the night of Erasmus celebrates the lasting influence of his work in contemporary days.

However, Erasmus's reputation and the interpretations of his work have varied greatly over time. Following his death, there was a long period of time when the citizens of the land all mourned his death. Moderate Catholics felt that he had been a leading figure in attempts to reform Church, while Protestants recognized his initial support for Luther's ideas and the groundwork he laid for the future Reformation. By the 1560s, however, there was a marked change in reception.

The Catholic Counter-Reformation movement often condemned Erasmus as having "laid the egg that hatched the Reformation." Their critique of him was based principally on his not being strong enough in his criticism of Luther, not seeing the dangers of a vernacular Bible and dabbling in dangerous scriptural criticism that weakened the Church's arguments against Arianism and other doctrines. All of his works were placed on the Index of Prohibited Books by Paul IV, and some of his works continued to be banned or viewed with caution in the later Index of Pius IV.

Protestant views of Erasmus fluctuate largely depending on region and period, with continuous support in his native Netherlands and in cities of the Upper Rhine area. However, following his death and in the late 16th century, Reformation supporters see Erasmus's critiques of Luther and lifelong support for the universal Catholic Church as damning. His reception was particularly cold by the Reformed Protestant groups.

By the coming of the Age of Enlightenment, however, Erasmus increasingly returned to become a more widely respected cultural symbol and was hailed as an important figure by increasingly broad groups.

[edit] Trivia

His scholarly name Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus comprises the following three elements: the Latin noun desiderium ("longing" or "desire"; the name being a genuine Late Latin name); the Greek adjective ???sµ??? (erasmios) meaning "beloved"; and the Latinized adjectival form for the city of Rotterdam (Roterodamus = "of Rotterdam").

Though he learned Latin in proper monasteries and universities, Erasmus largely taught himself Greek at the age of 30.

Several schools, faculties and universities in The Netherlands and Flanders are named after him. In addition, Erasmus Hall in Brooklyn, New York, USA, is also named for him.

The student exchange program in Europe in the 20th and 21st centuries, called the Erasmus programme, was named after him. Erasmus himself studied at different universities in 16th-century Europe. The name Erasmus programme is actually the acronym ERASMUS for European Region Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students.

In the film L' Auberge espagnole (The Spanish Apartment) (2002) by Cédric Klapisch about the Erasmus programme, he plays a role as a running gag. The protagonist sometimes sees an actor in Barcelona, dressed in a 16th-century outfit, and mistakens him for Erasmus.

In the 2004 election of De Grootste Nederlander (The Greatest Dutchman), he ended in fifth place. In the election of De Grootste Belg (The Greatest Belgian), he ended in 11th place in the Flemish edition of 2005.[edit] Selected works

Colloquia, which appeared at intervals from 1500 on

Apophthegmatum opus

Adagia

In Praise of Folly[edit] Representations of Erasmus

Holbein's studies of Erasmus's hands, in silverpoint and chalks, ca. 1523. (Louvre)The portraitist Hans Holbein the Younger made a profile half-length portrait in 1523, and Albrecht Dürer made an engraving of Erasmus in 1526.

Hans Holbein is considered to be the greatest portraitist of Erasmus, having painted no fewer than three, and as many as seven. His three profile portraits of Erasmus, two (nearly identical) profile portraits and one three-quarters view portrait were all painted in the same year, 1523. Erasmus used the Holbein portraits as gifts for his friends in England, such as William Warham, the Archbishop of Canterbury (as he writes in a letter to Warham regarding the gift portrait, Erasmus quips that "he might have something of Erasmus should God call him from this place.") Erasmus spoke favorably of Holbein as an artist and person, but later criticized Holbein whom he had accused of sponging off of various patrons to whom Erasmus had recommended, for purposes more of monetary gain than artistic endeavor.

Albrecht Dürer also produced portraits of Erasmus, in the form of an engraving and a preliminary charcoal sketch. Concerning the former Erasmus was decidedly unimpressed, declaring it an unfavorable likeness of him. Nevertheless, Erasmus and Dürer maintained a close friendship, with Dürer going so far as to sollicit Erasmus's support for the Lutheran cause, which Erasmus politely declined. Despite their disagreements, Erasmus wrote a glowing encomium about the artist, likening him to famous Greek painter of antiquity Apelles. Erasmus was deeply affected by his death in 1528.

Quentin Matsys produced the earliest known portraits of Erasmus, including an oil painting in 1517 and a medallion in 1519.[edit] Notes

^ Collected Works of Erasmus, vol. 1, p. 12 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974)

^ Metzger, Bruce. The Text of the New Testament, p. 96–103.[edit] Critical bibliography

Botley, Paul (2004). Latin Translation in the Renaissance: The Theory and Practice of Leonardo Bruni, Giannozzo Manetti and Desiderius Erasmus, London: Cambridge University Press.

Chantraine, Georges (1971). "Philosophie erasmienne et théologie lutérienne." "Mystère" et "Philosphie du Christ" selon Erasme, Brussels : Duculot, pp. 374-376.

Dockery, David S. (October 19, 1995). "The Foundation of Reformation Hermeneutics: A Fresh Look at Erasmus," Premise 2, no. 9, pp. 6–ff. (An appreciative look at Erasmus's contribution to biblical hermeneutics [interpretation methods] from an Evangelical Christian perspective.)

Gauss, C. (first published 1999). Introduction to 'The Prince' . New York: Signet, p. 11.

Hoffmann, Manfred (1994). Rhetoric and Theology: The Hermeneutic of Erasmus, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Hollis, Christopher (1931). Erasmus, London: Eyre & Spottiswode. (Concentrates on Erasmus' quarrels with Catholic hierarchy.)

Huizinga, Johan (1957). Erasmus and the Age of Reformation, New York: Harper Torchbooks. (Huizinga's text was translated from Dutch and first published by Charles Scribner's Sons in 1924. It is considered one of the foundational Erasmus biographies of the 20th century.)

Jardine, Lisa (1993). Erasmus, Man of Letters: The Construction of Charisma in Print, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1993. (Argues that Erasmus was extremely careful and skillful in creating, manipulating and managing his own image.)

Mansfield, Bruce E. (1979). Phoenix of His Age: Interpretations of Erasmus C. 1550-1750, Erasmus Studies 4, Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press. (Traces the reception and interpretations of Erasmus after his death.)

Metzger, Bruce (1992). The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 3rd edition: ISBN 0-19-507297-9 – (Discusses the origin of the Textus Receptus.)

Payne, John B. (1970). Erasmus: His Theology of the Sacraments, Richmond. Va.: John Knox Press. (This work pays great attention to Erasmus's own writings and analyzes the different aspects of his theology in light of his Catholic and Humanist influences. Payne conducted extensive work on UTP's Collected Works of Erasmus editions.)

Phillips, Margaret Mann (1949). Erasmus and the Northern Renaissance, Teach Yourself History Library series, London: Hodder & Stoughton. (An important classic on the topic.)

Panofsky, Erwin "Erasmus and the Visual Arts," Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. 32 (1969): 200-227. (A well known article about Erasmus and his relationships with Hans Holbein, Albrect Dürer and Quentin Matsys, and Erasmus's view on the visual arts.)

Rabil, Albert (1972). Erasmus and the New Testament: The Mind of a Christian Humanist, San Antonio, Tx.: Trinity University Press.

Stevens, Forrest Tyler (1994). "Erasmus's 'Tigress': The Language of Friendship, Pleasure and the Renaissance Letter" in Queering the Renaissance, Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. (An illuminating analysis of the letters to Servatius and Erasmus's De conscribendis epistolis.)

Tracy, James D. (1972). Erasmus: The Growth of a Mind, Travaux d'humanisme et renaissance, 126, Geneva: Droz. (One of the standard biographies.)[edit] See also

Rodolphus Agricola

Christian humanism

Erasmus Prize

Erasmus's correspondents

Erasmus Mobility Program

Erasmus Mundus Program ([1]) ([2])http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erasmus

(1466-1536)

Dutch philosopher and Humanist, Erasmus was born on October 27th, perhaps 1466, in Rotterdam. It is believed that he was the son of a priest, but there is some doubt about his name. It is thought his real name was Gerard Gerardson. The name 'Erasmus' might have been taken from the Greek word meaning 'beloved', but the correct spelling should be “Erasmius”, the name given to his godson, son of Johann Froben, his printer.Erasmus was sent to school at Gouda in Holland aged 4 years old. As he had a good voice he was sent to Utrecht and placed in the Cathedral choir but he had no gift for music and so when he was 9 years old he went to Deventer school where his natural academic ability blossomed. At 13 years old his parents died and he was left in the care of three guardians who wished him to become a monk because it was the easiest way to dispose of a ward. Erasmus was not at all happy at the monastic seminary at Hertogenbosch and both his health and education suffered. However his guardians were adamant that Erasmus’ future was to be in the priesthood and at 18 years old Erasmus reluctantly took the vows and became a Canon Regular in the Augustinian monastery at Stein, near Gouda. For the next 5 years Erasmus stayed at the monastery but it was during this time, whilst secretly reading a number of the best Latin authors, that he realised his life’s work lay beyond the cloisters. Things took a turn for the better when he was invited by the Bishop of Cambray, Henry de Bergis, to live with him as his Secretary. Soon after he took orders and the Bishop enabled him to go to Paris University to study classical literature where he stayed at Montaigu College. This was not a great move as far as his health was concerned, which was never good, as the work was hard, the food was poor, and the rooms were damp so he moved to rented accommodation and worked as a tutor to help fund his studies.

He soon became known in Paris as a very fine scholar, particularly in Latin which was then the general language of learning and international communications. One of his pupils, William Blunt, Lord Mountjoy, set up a pension of 100 crowns a year and soon after, in 1499, Erasmus paid his first visit to England. His acquaintance with Lord Mountjoy opened the doors of a new and influential world to Erasmus with opportunities to visit the royal court, where he first met the future Henry VIII, then a boy of 9, and the ancient University at Oxford. It was at Oxford that he met some of the men who had studied in Italy and were some of the earliest teachers of Greek; William Grocyn, William Latimer and Thomas Linacre. In London he also befriended two people who were to have a great influence on him: Thomas More and John Colet. More was reading law in London when they met whilst Colet was lecturing on St Paul’s Epistles and encouraged Erasmus to broaden his studies to embrace theology in particular. Over the next 10 years Erasmus divided his time between France, the Netherlands and England, always keeping in touch with his English humanist friends, and he also spent three years in Italy. In 1509, on his third visit to England, Erasmus was persuaded to settle and for the next 5 years he spent much of his time at Cambridge, staying at Queen’s College and lecturing in his new-found passion for theology and Greek. It was at this time, while he was staying at More’s house in 1511, that he wrote the famous work, “In Praise of Folly” offering a revealing insight on society in general, including the various abuses of the church and the selfish wars of Kings; as it was written in jest no-one took offence even though the meaning was clear. In 1512 he completed the translation of the New Testament into Greek and a year later, with Cambridge suffering from plague, he left the University and then in 1514 he left England for Basle where his New Testament work was printed by the famous printer, Froben. He also wrote a new Latin version of the New Testament as well as a series of Latin Paraphrases on all the books of the New Testament except Revelations so that they were more accessible to the ordinary reader’s mind. They were translated into English and every Parish Church had a copy.

People in the 14th century were not encouraged to think or reason for themselves. Erasmus, who was at the forefront in promoting the spread of knowledge that included the great writers of ancient Greece and Rome, felt that to encourage learning would turn ignorance about religious, state and daily life on its head He felt that true knowledge would encourage a better morality and a greater understanding between people. He sought to make things widely known by applying authors’ wisdom or wit to the circumstances of his own day. The Protestant Reformation, erupting with the publication of Martin Luther’s ’95 Theses’, was never fully supported by Erasmus, even though he is considered one of the leaders of the movement. Although he supported its ideals he was against the radicalism of the other leaders and in 1523 Erasmus condemned Luther’s methods in his work, “De Libero Aribitrio”. A pioneer in Church reform, Erasmus kept to his principles, his humanism always holding him back from what he felt were violent and sweeping reforms. This was something Erasmus came to be well respected for and it influenced the religious tolerance that finally emerged across Europe. Erasmus’ literary output was immense and continued right the way through his life until his death in 1536.

In 1503 he wrote “The Handbook of a Christian Knight”. He believed in rational piety and took a critical attitude to superstition. He was an opponent of religious bigotry, supported Luther's aims but was hostile to the results of the Reformation.

History tells us that Erasmus of Rotterdam has never had his due. In part, the reason being that he founded no church to perpetuate his memory. In consequence, he has lagged far behind not only the major reformers — Luther, Calvin, Zwingli and Melanchthon — but even the minor reformers such as Caspar Scwenfeld and the Anabaptists. A critical edition of his entire corpus has been undertaken at long last, and not by a church but by the Royal Dutch Academy out of national pride, of which Erasmus was entirely devoid.