Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

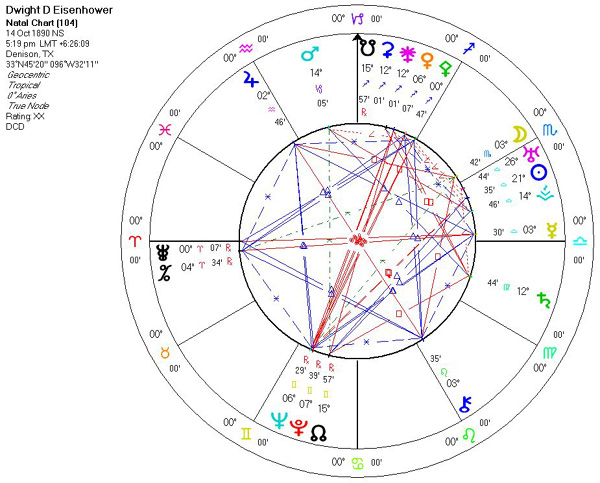

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

The most terrible job in warfare is to be a second lieutenant leading a platoon when you are on the battlefield.

(Mars in Capricorn conjunct MC.)The United States pledges … its determination to help solve the fearful atomic dilemma—to devote its entire heart and mind to finding the way by which the miraculous inventiveness of man shall not be dedicated to his death but consecrated to his life

The clearest way to show what the rule of law means to us in everyday life is to recall what has happened when there is no rule of law.

I never saw a pessimistic general win a battle.

(Jupiter in 11th house square Moon in Scorpio in 8th house.)The president cannot escape from his office.

(Saturn in 6th house.)History does not long entrust the care of freedom to the weak or the timid.

We are going to have peace even if we have to fight for it.

We seek peace, knowing that peace is the climate of freedom.

Peace and justice are two sides of the same coin.

Plans are nothing, planning is everything.

( Saturn in Virgo.)Politics should be the part-time profession of every citizen.

(Aries Asc.)The day before my inauguration President Eisenhower told me, "You'll find that no easy problems ever come to the President of the United States. If they are easy to solve, somebody else has solved them.

Only our individual faith in freedom can keep us free.

Whatever America hopes to bring to pass in the world must first come to pass in the heart of America.

An intellectual is a man who takes more words than necessary to tell more than he knows.

(Mercury in Libra.)Leadership is the art of getting someone else to do something you want done because he wants to do it.

You do not lead by hitting people over the head — that's assault, not leadership.

Though force can protect in emergency, only justice, fairness, consideration and cooperation can finally lead men to the dawn of eternal peace.

What counts is not necessarily the size of the dog in the fight — it's the size of the fight in the dog.

(Mars in Capricorn.)There is one thing about being President, no one can tell you when to sit down.

A people that values its privileges above its principles soon loses both.

Americans, indeed all freemen, remember that in the final choice, a soldier's pack is not so heavy a burden as a prisoner's chains.

The spirit of man is more important than mere physical strength, and the spiritual fiber of a nation than its wealth.

Don't join the book burners. Do not think you are going to conceal thoughts by concealing evidence that they ever existed. Don't be afraid to go into your library and read every book.

Freedom from fear and injustice and oppression will be ours only in the measure that men who value such freedom are ready to sustain its possession — to defend it against every thrust from within or without.

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed.

( Uranus in Libra.)I hate war as only a soldier who has lived it can, only as one who has seen its brutality, its futility, its stupidity.

Here in America we are descended in blood and in spirit from revolutionist and rebel men and women who dare to disssent from accepted doctrine. As their heirs, may we never confuse honest dissent with disloyal subversion.

The clearest way to show what the rule of law means to us in everyday life is to recall what has happened when there is no rule of law.

The problem in defense is how far you can go without destroying from within what you are trying to defend from without.

(Pluto conjunct Neptune opposition Venus?)When you are in any contest,you should work as if there were—to the very last minute—a chance to lose it. This is battle,This is politics,This is anything.

Farming looks mighty easy when your plow is a pencil and you're a thousand miles from the corn field.

Humility must always be the portion of any man who receives acclaim earned in the blood of his followers and the sacrifices of his friends.

If all that Americans want is security, they can go to prison. They'll have enough to eat, a bed and roof over their heads. But if an American wants to preserve his dignity and his equality as a human Being, he must not bow his neck to any dictatorial government.

We succeed only as we identify in life, or in war, or in anything else, a single overriding objective, and make all other considerations bend to that one objective.

(Venus in Sagittarius?)When people speak to you about a preventive war, you tell them to go and fight it. After my experience, I have come to hate war. War settles nothing.

Unless each day can be looked back upon by an individual as one in which he has had some fun, some joy, some real satisfaction, that day is a loss."

The same day I saw my first horror camp, I visited every nook and cranny. I felt it my duty to be in a position from then on to testify about these things in case there ever grew up at home the belief or assumption that the stories of Nazi brutality were just propaganda.

Any man who wants to be president is either an egomaniac or crazy.

Controlled, universal disarmament is the imperative of our time. The demand for it by the hundreds of millions whose chief concern is the long future of themselves and their children will, I hope, become so universal and so insistent that no man, no government anywhere, can withstand it.

I despise people who go to the gutter on either the right or the left and hurl rocks at those in the center.I think that people want peace so much that one of these days government had better get out of their way and let them have it.If a problem cannot be solved, enlarge it.If men can develop weapons that are so terrifying as to make the thought of global war include almost a sentence for suicide, you would think that man's intelligence and his comprehension... would include also his ability to find a peaceful solution.Only strength can cooperate. Weakness can only beg.

Bringing to the Presidency his prestige as commanding general of the victorious forces in Europe during World War II, Dwight D. Eisenhower obtained a truce in Korea and worked incessantly during his two terms to ease the tensions of the Cold War. He pursued the moderate policies of "Modern Republicanism," pointing out as he left office, "America is today the strongest, most influential, and most productive nation in the world."

Born in Texas in 1890, brought up in Abilene, Kansas, Eisenhower was the third of seven sons. He excelled in sports in high school, and received an appointment to West Point. Stationed in Texas as a second lieutenant, he met Mamie Geneva Doud, whom he married in 1916.

In his early Army career, he excelled in staff assignments, serving under Generals John J. Pershing, Douglas MacArthur, and Walter Krueger. After Pearl Harbor, General George C. Marshall called him to Washington for a war plans assignment. He commanded the Allied Forces landing in North Africa in November 1942; on D-Day, 1944, he was Supreme Commander of the troops invading France.

After the war, he became President of Columbia University, then took leave to assume supreme command over the new NATO forces being assembled in 1951. Republican emissaries to his headquarters near Paris persuaded him to run for President in 1952.

"I like Ike" was an irresistible slogan; Eisenhower won a sweeping victory.

Negotiating from military strength, he tried to reduce the strains of the Cold War. In 1953, the signing of a truce brought an armed peace along the border of South Korea. The death of Stalin the same year caused shifts in relations with Russia.

New Russian leaders consented to a peace treaty neutralizing Austria. Meanwhile, both Russia and the United States had developed hydrogen bombs. With the threat of such destructive force hanging over the world, Eisenhower, with the leaders of the British, French, and Russian governments, met at Geneva in July 1955.

The President proposed that the United States and Russia exchange blueprints of each other's military establishments and "provide within our countries facilities for aerial photography to the other country." The Russians greeted the proposal with silence, but were so cordial throughout the meetings that tensions relaxed.

Suddenly, in September 1955, Eisenhower suffered a heart attack in Denver, Colorado. After seven weeks he left the hospital, and in February 1956 doctors reported his recovery. In November he was elected for his second term.

In domestic policy the President pursued a middle course, continuing most of the New Deal and Fair Deal programs, emphasizing a balanced budget. As desegregation of schools began, he sent troops into Little Rock, Arkansas, to assure compliance with the orders of a Federal court; he also ordered the complete desegregation of the Armed Forces. "There must be no second class citizens in this country," he wrote.

Eisenhower concentrated on maintaining world peace. He watched with pleasure the development of his "atoms for peace" program--the loan of American uranium to "have not" nations for peaceful purposes.

Before he left office in January 1961, for his farm in Gettysburg, he urged the necessity of maintaining an adequate military strength, but cautioned that vast, long-continued military expenditures could breed potential dangers to our way of life. He concluded with a prayer for peace "in the goodness of time." Both themes remained timely and urgent when he died, after a long illness, on March 28, 1969.

Date of Birth Tuesday, October 14, 1890

Place of Birth: Denison, TexasDate of Death: Friday, March 28, 1969

Eisenhower was born in Denison, Texas, the third of seven sons born to David Jacob Eisenhower and Ida Elizabeth Stover. The Eisenhower family was of German descent, but had lived in America since the 18th century. The family moved to Abilene, Kansas, in 1892. Eisenhower graduated from Abilene High School in 1909 and he worked at Belle Springs Creamery from 1909 to 1911.

Eisenhower married Mamie Geneva Doud (1896-1979), of Denver, Colorado on Saturday, July 1, 1916. They had two children, Doud Dwight Eisenhower (1917-1921), and John Sheldon David Doud Eisenhower (born 1922). John Eisenhower served in the United States Army, then became an author and served as U.S. Ambassador to Belgium. One of John Eisenhower's sons, David Eisenhower, married Richard Nixon's daughter Julie in 1968.

Military career

Eisenhower enrolled at the United States Military Academy, West Point, New York, in June, 1911 and graduated in 1915. He served with the infantry until 1918 at various camps in Texas and Georgia. He then served with the Tank Corps from 1918 to 1922 at Camp Meade, Maryland and other places. He was promoted to Captain in 1917 and Major in 1920. In 1922 he was assigned as executive officer to General Fox Conner in the Panama Canal Zone, where he served until 1924. In 1925 and 1926 he attended the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and then served as a battalion commander, at Fort Benning, Georgia, until 1927.During the late 1920s and early 1930s Eisenhower's career in the peacetime Army stagnated. He was assigned to the American Battle Monuments Commission, directed by General John Pershing, then to the Army War College in Washington, D.C, and then served as executive officer to General George V. Moseley, Assistant Secretary of War, from 1929 to 1933. He then served as chief military aide to General Douglas MacArthur, Army Chief of Staff, until 1935, when he accompanied MacArthur to the Philippines, where he served as assistant military advisor to the Philippine Government. He was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in 1936.

Eisenhower returned to the U.S. in 1939 and held a series of staff positions in Washington, D.C., California, and Texas. In June 1941 was appointed Chief of Staff to General Walter Kreuger, Commander of the 3rd Army, at Fort Sam Houston, Texas. He was promoted to Brigadier-General in September 1941. Although his administrative abilities had been noticed, on the eve of the U.S. entry into World War II he had never held an active command and was far from being considered as a potential commander of major operations.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Eisenhower was assigned to the General Staff in Washington, where he served until June 1942. He was appointed Deputy Chief in charge of Pacific Defenses under the Chief of War Plans Division, General Leonard Gerow, and then succeeded Gerow as Chief of the War Plans Division. Then he was appointed Assistant Chief of Staff in charge of Operations Division under the Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall. It was his close association with Marshall which finally brought Eisenhower to senior command positions. Marshall recognised his great organisational and administrative abilities.

Wartime commander

In June 1942 Eisenhower was designated Commanding General, European Theater, based in London. Here he planned and executed the Allied landings in Morocco and Algeria, codenamed Operation Torch. He was Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Forces in North Africa from November 1942. In December 1943 he was appointed Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Forces, charged with planning and carrying out the Allied invasion of France, Operation Overlord, in June 1944. He commanded all Allied forces in the Normandy invasion, which took place on D-Day, June 6, 1944. On December 20, he was promoted to General of the Army. By the end of 1944 Eisenhower was in overall command of armed forces comprising 4.5 million men and women.In these positions Eisenhower showed his great talents for leadership and diplomacy. Although he had never seen action himself, he won the respect of front-line commanders such as Omar Bradley and George Patton. He dealt skillfully with difficult allies such as Winston Churchill, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery and General Charles de Gaulle. He had fundamental disagreements with Churchill and Montgomery over questions of strategy, but these rarely upset his relationships with them. He negotiated with Soviet commanders such as Marshall Zhukov, and sometimes directly with Stalin, such was the confidence that President Roosevelt had in him.

He was offered the Medal of Honor for his leadership in the European Theather, but refused it, saying that it should be reserved for bravery and valour.

Following the German unconditional surrender on May 8, 1945, Eisenhower was appointed Military Governor of the U.S. Occupation Zone, based in Frankfurt-am-Main. Germany was divided into four Occupation Zones, one each for the United States, Britain, France and the Soviet Union. His most controversial decisions involved captured German soldiers and their alleged mistreatment. Eisenhower ordered the status of German prisoners of war or POWs in U.S. custody changed to that of Disarmed Enemy Forces or DEFs.

Eisenhower was named Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army in November 1945 and in December 1950 he was named Supreme Commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, and given operational command of NATO forces in Europe. Eisenhower retired from active service on May 31, 1952, on entering politics.

Eisenhower in politics

Eisenhower had been chosen as President of Columbia University in July 1948, giving him a legal residence in New York City. He had been mentioned as a possible presidential candidate since 1945. Unlike MacArthur, who had actively pursued the Republican presidential nomination since 1936, Eisenhower had shown little interest in politics. It was not even known if he was a Republican or a Democrat.

Some writers have said that Democratic President Harry S. Truman offered to stand aside in favor of Eisenhower at the 1948 presidential election, although Truman always denied this. In the lead-up to the 1952 election, he was pursued as a candidate by both the Democrats and the Republicans. Eisenhower initially refused to run, but was eventually persuaded to allow his name to be put forward for the Republican nomination. He said he chose the Republicans because the Democrats had been in office for 20 years and the country needed a change. He defeated Senator Robert Taft of Ohio for the nomination.

In the lead-up to the presidential election, Eisenhower campaigned as a "non-politician," never mentioning his main competitor, Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois, by name. Instead he allowed other Republicans to run a Cold War campaign accusing the Democrats of being "soft on Communism" while he preserved his genial public image. For this reason he chose a hard-line, anti-Communist senator from California, Richard Nixon, as his running mate. Eisenhower, as one of the country's two greatest war heroes, but with a much more congenial personality than MacArthur's, was always likely to be elected. Eisenhower and Nixon won the November election with 442 electoral votes, against Stevenson's 89.

Eisenhower as President

Foreign affairs

Eisenhower's presidency was dominated by the Cold War, the prolonged confrontation with the Soviet Union which had begun during Truman's term of office. His Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, led the fight against the Communist powers with great zeal, but despite the urgings of the right wing of the Republican Party, Eisenhower pursued a generally moderate course, accepting the doctrine of containment originally developed by George Kennan. During his campaign Eisenhower had promised to end the stalemated Korean War, and a cease-fire was signed in July 1953. He signed defense treaties with South Korea and the Republic of China, and formed an alliance anti-Communist Asian and Pacific countries, SEATO, to halt the spread of Communism in Asia.In 1956 Eisenhower strongly disapproved of the actions of Britain and France in sending troops to Egypt in the dispute over control of the Suez Canal (see Suez crisis). He used the economic power of the U.S. over its European allies to force them to back down and withdraw from Egypt. During his second term he became increasingly involved in Middle Eastern affairs, sending troops to Lebanon in 1957, and supporting the coup in Iran which restored Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi to power.

Under Eisenhower's presidency the U.S. became the world's first global nuclear power, and the world lived in fear of a Third World War involving nuclear weapons. But Eisenhower hoped that after the death of Stalin in 1953 it would be possible to come to an agreement with his successors and halt the nuclear arms race. Several attempts were made to hold a summit with the Soviet leaders, the last such attempt failing in 1960 when Nikita Khrushchev withdrew following the shooting down of a U-2 spy plane over the Soviet Union.

Domestic affairs (Modern Republicanism)

Like most Republican presidents Eisenhower believed that a free enterprise economy should run itself and took little interest in domestic policy. Although his 1952 landslide gave the Republicans control of both houses of the Congress, the Democrats regained control in 1954, limiting his freedom of action on domestic policy. He forged a good relationship with Congressional leaders, particularly House Speaker Sam Rayburn.Eisenhower appointed a Cabinet full of businessmen and left them to run the country. He was happy for them to take the credit for domestic policy and allow him to concentrate on foreign affairs. On the two major issues of the 1950s, Communism and the civil rights for Black Americans, he was reluctant to exercise leadership unless forced to. In 1957, however, he sent federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas after Governor Orval Faubus attempted to defy a Supreme Court ruling that ordered the desegregation of all public schools.

Eisenhower was also criticized for not taking a public stand against Senator Joseph McCarthy's anti-communist campaigns, although he privately hated him for his attacks on his friend and World War II colleague, General George Marshall, who had been Secretary of State under Truman. He said privately "I just won't get down in the gutter with that man," but this was little comfort to the many people whose reputations were ruined by McCarthy's allegations of Communist conspiracies.

Eisenhower endorsed the United States Interstate Highway Act, in 1956. It was the largest public works program in United States history, providing a 41,000-mile highway system. Eisenhower had been impressed during the war with the German Autobahn system and also recalled his own involvement in a military convoy in 1919 that took 62 days to cross the United States. Another achievement was a 20% increase in family income during his presidency, which he was very proud of. He added a tenth cabinet position, creating the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. He achieved a balanced budget in three of the years that he was President.

Eisenhower retained his popularity throughout his presidency. In 1956 he was re-elected by an even wider margin than in 1952, again defeating Stevenson and carrying such traditional Democratic states as Texas and Tennessee. But once he left office his reputation declined, and he was seen as having been a do-nothing President. This was partly because of the contrast between Eisenhower and his young activist successor, John F. Kennedy, but also due to his reluctance to support the civil rights movement or to stop McCarthyism, and these were held against him during the liberal climate of the 1960s and 1970s. In recent years Eisenhower's reputation has recovered. A recent poll of historians rated him number eleven among all the Presidents. Nevertheless, the judgement of some historians is that Eisenhower's greatest achievements were those of his wartime military commands.

Eisenhower had mixed feelings about his Vice President, Richard Nixon, and only reluctantly endorsed him as the Republican candidate at the 1960 Presidential election. Nixon campaigned against Kennedy on the great experience he had acquired in eight years as Vice President, but when Eisenhower was asked to name a decision Nixon had been responsible for in that time, he replied (intending a joke): "Give me a week and I might think of something." This was a severe blow to Nixon and he blamed Eisenhower for his narrow loss to Kennedy.

Although Eisenhower lived for most of the postwar years at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, the Eisenhower Presidential Library is located in Abilene, Kansas, where he grew up. Eisenhower and his wife are buried in a small chapel there, called the Place of Meditation.

October 14, 1890 -

March 28, 1969On December 12, 1941, just five days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Brigadier General Dwight D. Eisenhower received the phone call that would alter the course of his life forever. At the time, Eisenhower was at the top of his professional form; competent in his work and remarkably self-confident in his demeanor. Since returning from the Philippines in late 1939, he had completed a series of stateside assignments that fulfilled his deep-seated desire to work directly with troops. In June of 1941, he had been transferred here, to Ft. Sam Houston, where it had all begun some 26 years before. On the other end of the line was the voice of Colonel Walter Bedell Smith, secretary of the General Staff, insisting that "The Chief," General George C. Marshall, wanted him in Washington-immediately.

With apprehension and dread at the prospect of returning to a staff job and sitting out the war, Eisenhower instructed his aide to pack a small duffel, assuring Mamie he wouldn't be gone long. When Eisenhower arrived at the Army Chief of Staff's office in Washington, D.C., Marshall took him aside and delivered a 20-minute briefing on the status of the United States military situation in the Pacific. When he had finished, General Marshall had just one question: "What should be our general line of action?" Eisenhower, momentarily taken aback, asked for a few hours and a desk; sat down and typed "Steps to Be Taken;" and began to think it through.Dwight David Eisenhower, was the third of seven sons born to David and Ida Stover Eisenhower; the only one born outside of Dickinson County, Kansas. After a failed business venture in Hope, Kansas, the Eisenhowers moved to Denison, Texas, where David found a job cleaning train locomotives. In a tiny house, a few feet from the railroad tracks, "David Dwight" Eisenhower was born on October 14, 1890. When Dwight was about eighteen months old, David moved his family back to Abilene because his brother-in-law, Chris Musser, had offered him a job at the Belle Springs Creamery.

David Jacob Eisenhower had homesteaded with his parents in Dickinson County, Kansas, in 1878. Members of a prosperous religious group from the Susquehanna Valley of Pennsylvania, they came to Kansas to buy rich and affordable farmland. A sect of the Mennonites, they called themselves the "Plain People." In Dickinson County, the group was more commonly known as the "River Brethren." Ida Stover and David Eisenhower met, as students, at Lane University in LeCompton, Kansas, where they married. In 1898, six years after returning from Texas, the Eisenhowers and six sons--Paul had died of diphtheria in 1896 at the age of three--moved into the house on Southeast Fourth Street that would become the legendary Eisenhower boyhood home.

Life at the turn of the century in small-town Abilene was filled with lessons to be learned and an abundance of adventure for an energetic, fun-loving, and handsome young man named Dwight Eisenhower. The part of Abilene that lay to the south of the Union Pacific tracks had been a wicked cowtown just a generation before, and young Dwight was enthralled with old-timers' stories of its "Wild West" days. Throughout his life, Dwight E. Eisenhower never lost his fascination with the history of the American West.

At a time when a high school education was considered a luxury for most, all the Eisenhower boys graduated, and, at their parents' urging, dared to dream of even a college education. Dwight had been working for two years at the Belle Springs Creamery after his high school graduation in 1909--helping support brother Edgar though college at the University of Michigan--when his friend, Swede Hazlett, encouraged him to consider applying for an appointment to the Naval Academy at Annapolis. Eisenhower passed entrance exams for both Annapolis and West Point, but was past the age of admission for the Naval Academy. Kansas Senator Joseph Bristow recommended him for an appointment to West Point in 1911, which he received.

The West Point years were formative ones for Eisenhower. He learned to endure the pressures and indignities of the Plebe year; and, in turn, discovered his own acute distaste for the hazing he was expected to inflict upon others in his Yearling year. On the football field, Eisenhower experienced the exultation of stardom and crushing disappointment when a series of knee injuries brought his glory days to an abrupt and painful end. In bitter reaction, Dwight Eisenhower smoked too much, studied too little, and accumulated an impressive list of demerits. Despite this setback, Eisenhower emerged as a natural leader, serving as junior varsity football coach and yell leader. And, even though he did not apply himself academically at West Point, Eisenhower still managed to graduate in the upper half of his class in 1915, the one that would be later known as the class "The Stars Fell On."

Following graduation, newly commissioned second lieutenant Eisenhower's first post assignment was Ft. Sam Houston, Texas. On a beautiful October day in 1915, Eisenhower was on duty, assigned to walk the post and inspect the guard. Fellow soldier and new friend, Gee Gerow, recognized Eisenhower from across the street and beckoned him to join the casual lawn party where the Douds of Denver were among the guests. Although he had recently "sworn off women"--once he had met eighteen-year-old Miss Mamie Geneva Doud, he pursued her with singular determination. Nine months later, July 1, 1916, they were married in the Doud home, and set out on a ten-day honeymoon in Colorado and on to Kansas to visit Dwight's parents and brother Milton at Kansas State College.

Those first years took Eisenhower to military posts in Texas, Georgia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and, then, back again to Georgia and Maryland. In some respects, these were happy years; in others, difficult. He and Mamie became the proud parents of Doud Dwight "Icky," in 1917, and then felt their world fall apart when he died, suddenly, of scarlet fever at age three. Eisenhower had initially balked at being assigned to coach the post's football team; however, he thoroughly enjoyed his role as teacher. Too, he felt great satisfaction training World War I recruits for effective overseas duty. Yet, he was very impatient for his own chance to ship out for France. Eisenhower applied, reapplied, and lobbied his superiors for an assignment to combat duty--even to the point of reprimand--and was resentful at having missed out on "his" war. For two months in the summer of 1919, Eisenhower volunteered to participate as a Tank Corps observer in the War Department's First Transcontinental Motor Convoy. It was often a frustrating journey: a train of trucks moving little more than six miles an hour across the country, broken down or mired in mud on a daily basis.

From 1922 to 1924, Eisenhower served as executive officer to General Fox Conner, a highly respected Army officer, in the Panama Canal Zone. Conner assumed the role of mentor to the younger Eisenhower, a decision that proved to be instrumental in the advancement of his career. Under Conner's tutelage, Eisenhower immersed himself in seminal works of history, military science, and philosophy. It was Conner who explained the inevitability of the coming world war to Eisenhower. With Conner's assistance, Eisenhower was accepted into the Command and General Staff School at Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas, the army's elite graduate school. In 1926, he graduated first in a class of 245 of the Army's finest young officers. Eisenhower had established a reputation for himself among officers of the small, peacetime, United States Army.

While in Fort Benning in 1927, Eisenhower was selected by General John "Black Jack" Pershing to write for the American Battle Monuments Commission in Washington and Paris. It was in this period that Eisenhower was introduced to the geography, cultures, and people of Europe; knowledge that would prove invaluable little more than a decade later. His tour completed in 1929, Eisenhower reported to the War Department. One of his assignments was to develop a plan to mobilize manpower and matériel for the Army should there be another war. It was from this position, that he was transferred to serve as chief military aide--largely to write speeches, reports and policy papers--under Douglas MacArthur, U.S. Army Chief of Staff in 1933.

In 1935, Eisenhower accompanied MacArthur to the Philippines as assistant military advisor, and there he remained--less than enthusiastic--until late in 1939. His primary mission, to build a viable Filipino Army, was to prove both frustrating and elusive. As the end of his assignment approached, Europe was, once again, at war. Despite MacArthur's pressure to remain in the Philippines and President Quezon's handsome offer of a blank contract for his services, Eisenhower was never tempted. He was not going to miss this war.

Stateside, in early 1940, Eisenhower was briefly stationed at Ft. Ord, California, then, received a more permanent assignment to Ft. Lewis, Washington. For the next two years, through late 1941, Eisenhower's assignments gave him many opportunities to exercise his natural leadership talents. All the experience and skills he had honed over twenty-five years served him very well; it was a happy time for Eisenhower.

In June 1941, Colonel Eisenhower was transferred to Ft. Sam Houston. Here he served as Chief of Staff for the Third Army, under General Walter Krueger. Eisenhower received national attention for his bold leadership in the Louisiana Maneuvers in August and September of 1941 when the Third Army decisively routed the Second Army. Only a few months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Eisenhower was promoted to brigadier general.

As a result of that December 12 summons to Washington, Eisenhower was transferred to the War Plans Division in Washington, DC, where Marshall tested his abilities with an amazing array of responsibilities in rapid succession. The Army Chief of Staff was impressed with Eisenhower's thinking, organizational, and people skills; in turn, Eisenhower was promoted to Major General by March of 1942. Eisenhower's prediction to Mamie-that he would not be gone long, had been ironic at best.

In May 1942, Eisenhower arrived in England on a special mission to build cooperation among the Allies as Commanding General, European Theater, and so began his meteoric rise in rank and fame. By November, he was named Commander-in-Chief, Allied Forces, North Africa, and carried out Operation Torch. In 1943, Eisenhower had his second test as Commander of the Allied invasions of Sicily and Italy. Thereafter, the time had come to plan the gargantuan land, sea, and air forces that would become more commonly known as D-Day: the Allied Invasion of the continent. In December 1943, Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Forces, and the planning of Operation Overlord began in earnest.

June 6, 1944, D-day, was the beginning of the end for the war in Europe. Eisenhower was promoted to the rank of General of the Army (5 stars) in December of that year. When Germany surrendered in May 1945, Eisenhower was appointed Military Governor, US Occupied Zone. By then, Dwight D. Eisenhower was an international celebrity; he had earned the respect, admiration, and affection of people around the world. Allied victory in Europe culminated in joyous exhaustion. Eisenhower quickly became the centerpiece of speeches, grand parades, and throngs of admirers as grateful nations throughout Europe honored him. In June of 1945, Eisenhower returned to a hometown hero's welcome in Abilene, where her citizens honored him as they had no other.

Five months later, November 1945, Eisenhower was selected as Chief of Staff, US Army. Nearly three years later, he was inaugurated as President of Columbia University, where he remained until the end of 1950, never far from the decision making on post-war national security policy. In December of 1950, on leave from Columbia University, Eisenhower was appointed the first Supreme Allied Commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Here he labored with Allied nations to build an organization around the idea of "concerted, collective, unified action." Eisenhower took a nearly impossible task, and turned his vision for Europe and the United States into a reality. Throughout this time, the "Draft Eisenhower" presidential grassroots effort took shape and swelled to a crescendo that he could no longer ignore. In preparation for what was to come, Eisenhower retired from active service, resigned his commission, and headed home to Abilene, to formally announce his candidacy for the Republican nomination for President of the United States.

Dwight David Eisenhower was elected the 34th President* of the United States on November 4, 1952. Four years later, he was reelected to a second term by an even wider margin. "Peace and Prosperity" became the watchwords of the Eisenhower years. Ending the war in Korea was only the first of many foreign policy challenges Eisenhower faced throughout his presidency. Other Cold War crises erupted in Lebanon, Suez, Berlin, Hungary, the Taiwan Straits, and Cuba. When confronted with possible US military intervention in Vietnam after the defeat of the French colonials, Eisenhower declined to involve the United States. Throughout his presidency, he worked hard to contain communism and, at the same time, was vigorous in his efforts to forge improved relations with the Soviet Union. When an American U-2 reconnaissance plane was shot down over Soviet territory, his hopes for détente, during his watch, were dashed.

Although criticized by some historians for a lack of leadership on racial issues, President Eisenhower supported and signed the 1957 and 1960 Civil Rights Acts, and ordered federal troops to Little Rock to enforce the desegregation of Central High School. Likewise, his decision to work behind the scenes to defeat Senator Joseph McCarthy, rather than confront his excesses directly, engendered the criticism of many. Eisenhower argued that to lower himself to the same level as McCarthy might confer upon the Senator a significance that would only enhance McCarthy's credibility.

Americans enjoyed a strong, expanding economy under Eisenhower, demonstrated by solid economic growth, little inflation, and low unemployment. Balancing the budget was an Eisenhower priority tempered with a sincere concern for the common good. Eisenhower expanded social security, increased the minimum wage, and established the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW). During the Eisenhower years, the Interstate Highway System and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) were created, and space exploration began. Near the end of his presidency, in 1959, Alaska and Hawaii became the 49th and 50th states of the Union.

On January 17, 1961, President Eisenhower bid farewell to the nation in a speech that is best remembered for his characterization of the "Military-Industrial Complex," and his warning of dire consequences to our personal freedoms and self-government should its power go unchecked. January 20, 1961, Dwight D. Eisenhower left office for a much-anticipated retirement. For half a century, he had striven to live the West Point motto: Duty, Honor, and Country, to the very best of his ability. The enormous pressures and heavy responsibilities of the last twenty years, particularly, had exacted a toll on his health. As he left public life, the American people held him in the highest regard,* and felt great affection for both him and Mamie.

Gettysburg Farm is located not far from the very place his grandfather had left more than eighty years before on a pioneer's journey that took the Eisenhowers to Kansas. Now, Dwight and Mamie--private citizens--returned there, looking forward to spending time together. With John's family living close by, the retirement years promised to be all they had dreamed.

The days passed with a variety of leisure activities; golf and painting, highest on the list. Eisenhower derived great satisfaction from raising livestock, gardening, and generally puttering around the farm. Afternoons were often spent with Mamie on the glassed-in porch, reading, painting, playing cards, and watching their favorite television programs. Guests to Gettysburg were often treated to a meal cooked by none other than the former President himself. The Eisenhowers indulged in travel, and each winter found them, surrounded by friends and family, at their Palm Desert, California, home. Eisenhower wrote his memoirs, and carried on a voluminous correspondence with old friends and associates. Frequently, Presidents Kennedy and Johnson sought his counsel, and approval, in his new role as Elder Statesman. Looking back over the extraordinary experiences of his life, Eisenhower enjoyed most reminiscing about his boyhood in Abilene and his West Point years.

The last year of Eisenhower's life was spent at Walter Reed Army Hospital as his health rapidly declined. Thirteen years earlier, he had suffered a near-fatal heart attack, and now a weakening heart was slowly ending his life. Mamie remained by his side, living in a small room just off the presidential suite. On March 28, 1969, Dwight D. Eisenhower uttered his last words, "I want to go; God take me." His heart gave up its struggle and he died peacefully. Following a state funeral in Washington, DC, Eisenhower was honored with a full military funeral in his beloved Abilene on April 2. Just as he had planned it, Dwight David Eisenhower was buried in a modest chapel, on the grounds of the Eisenhower Center, where he joined Doud Dwight, the son he and Mamie had lost nearly fifty years before. Dwight D. Eisenhower had returned home to stay.