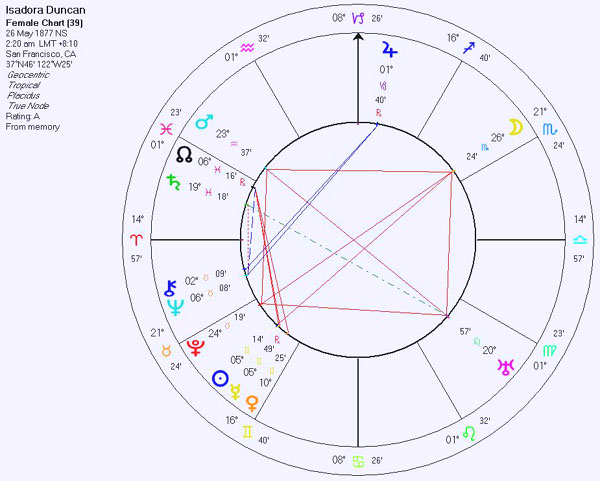

Isadora Duncan

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

Duncan was accidentally strangled when her long scarf caught in the wheel of her car; her parting words were spoken in French. " Farewell, my friends. I go to glory. "

We may not all break the Ten Commandments, but we are certainly all capable of it. Within us lurks the breaker of all laws, ready to spring out at the first real opportunity.

(URANUS IN THE 5TH HOUSE SQUARE PLUTO IN THE 2ND.)Virtuous people are simply those who have ... not been tempted sufficiently, because they live in a vegetative state, or because their purposes are so concentrated in one direction that they have not had the leisure to glance around them.

(SCORPIO MOON!) Any intelligent woman who reads the marriage contract and then goes into it, deserves all the consequences.Others loved themselves, money, theories, power: Lenin loved his fellow men.... Lenin was God, as Christ was God, because God is Love and Christ and Lenin were all Love!Perhaps he was a bit different from other people, but what really sympathetic person is not a little mad?

The first essential in writing about anything is that the writer should have no experience of the matter.

(ahem, she was a dancer.) The only dance masters I could have were Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Walt Whitman and Nietzsche."People don't live nowadays: they get about ten percent out of life

The finest inheritance you can give to a child is to allow it to make its own way, completely on its own feet.

Art is not necessary at all. All that is necessary to make this world a better place to live in is to love --to love as Christ loved, as Buddha loved.

(NEPTUNE CONJUNCT CHIRON IN TAURUS TRINE JUPITER.)What one has not experienced, one will never understand in print. Dancing: The Highest Intelligence in the Freest Body.

I do not teach children, I give them joy.

(URANUS IN LEO IN 5TH HOUSE.)I have discovered the dance. I have discovered the art which has been lost for two thousand years.We are fed nothing but lies. It begins with lies and half our lives we live with lies.The artist is the only lover; he alone has the pure vision of beauty, and love is the vision of the soul when it is permitted to gaze upon immortal beauty...As a child, I danced on the sea beach...the movement of the waves rocked with my soul...could I dance as they...their eternal message of rhythm and harmony?A dancer, if she is great, can give to the people something that they can carry with them forever. They can never forget it, and it has changed them, though they may never know it. There are likewise three kinds of dancers: first, those who consider dancing as a sort of gymnastic drill, made up of impersonal and graceful arabesques; second, those who, by concentrating their minds, lead the body into the rhythm of a desired emotion, expressing a remembered feeling or experience. And finally, there are those who convert the body into a luminous fluidity, surrendering it to the inspiration of the soul. *Isadora Duncan*Man must speak, then sing, then dance. The speaking is the brain, the thinking man. The singing is the emotion. The dancing is the Dionysian ecstasy which carries away all. You were once wild here, don't let them tame youYes, I am a revolutionist. All true artists are revolutionists.

(URANUS IN LEO IN 5TH HOUSE OPPOSITION MARS IN AQUARIUS IN 11TH HOUSE)

Isadora Duncan (May 27, 1878 - September 14, 1927) was an American dancer.

Born Dora Angela Duncanon in San Francisco, California, she is considered the Mother of Modern Dance. Although never very popular in the United States, she entertained throughout Europe, and moved to Paris, France in 1900. There, she lived at the apartment hotel at no. 9, rue Delambre in Montparnasse in the midst of the growing artistic community gathered there. She told friends that in the summer she used to dance in the nearby Luxembourg Garden, the most popular park in Paris, when it opened at five in the morning.

Both in her professional and her private life, she flouted traditional mores and morality. One of her lovers was the theatre designer, Gordon Craig; another was Paris Singer, one of the many sons of Isaac Singer the sewing machine magnate; she bore a child by each of them. Her private life was subject to considerable scandal, especially following the tragic drowning of her children in an accident on the Seine River in 1913. In her last United States tour in 1922-23, she waved a red scarf and bared her breast on stage in Boston, proclaiming, "This red! So am I!".

Montparnasse's developing Bohemian environment did not suit her, and in 1909, she moved to two large apartments at 5 Rue Danton where she lived on the ground floor and used the first floor for her dance school. She danced her own style of dance and believed that ballet was "ugly and against nature and gained a wide following that allowed her to set up a school to teach. She became so famous that she inspired artists and authors to create sculpture, jewelry, poetry, novels,photographs, watercolors, prints and paintings. When the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées was built in 1913, her face was carved in the bas-relief by sculptor Antoine Bourdelle and painted in the murals by Maurice Denis.

In 1922 she married the Russian poet, Sergei Yesenin who was 17 years her junior. Yesenin accompanied her on a tour of Europe but his frequent drunken rages, resulting in the repeated destruction of furniture and the smashing of the doors and windows of their hotel rooms, brought a great deal of negative publicity. The following year he left Duncan and returned to Moscow where he soon suffered a mental breakdown and had to be institutionalized. Released from hospital, he immediately committed suicide on December 28, 1925.

Duncan often wore scarves which trailed behind her, and this caused her death in a freak accident in Nice, France. She was killed when her scarf caught in the wheel of her friend Ivan Falchetto's Bugatti automobile, in which she was a passenger. As the driver sped off, the long cloth wrapped around the vehicle's axle. Ms. Duncan was yanked violently from the car and dragged for several yards before the driver realized what had happened. She died almost instantly from a broken neck.

She wrote an autobiography, Ma Vie, and her life story was made into a movie, Isadora, in 1968.

Isadora Duncan was cremated, and her ashes were placed in the columbarium of Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, France.

NAME: Isadora Duncan, born Dora Angela Duncan

DATE OF BIRTH: May 27, 1878

PLACE OF BIRTH: San Francisco, California

DATE OF DEATH: September 14, 1927

PLACE OF DEATH: Nice, France. She died when her scarf accidentally became tangled in the wheels of a Bugatti sports car, resulting in a broken neck.FAMILY BACKGROUND: Isadora was the second daughter and the youngest of four children to parents Joseph Charles and Dora Gray Duncan. Her father was a poet and her mother was a pianist and music teacher. When Isadora's parents married, her father was divorced with four children and 30 years her senior. He supported his family through running a lottery, publishing three newspapers, owning a private art gallery, directing an auction business and owning a bank. When the bank fell into financial ruin, he abandoned Isadora's family, moved to Los Angeles where he divorced and remarried again.

Isadora did not believe in marriage but did have love affairs with stage designer Gordon Graig and millionaire (Paris) Eugene Singer and had a child by each. Her children, Deirdre and Patrick were tragically and accidentally drowned in 1913 while with their English governess. Later in her life she married Russian poet, Sergei Esenin in 1922 but separated shortly after.

EDUCATION: As a child, she learned unconventionally to "listen to the music with your soul." Her mother instilled in Isadora a love for dance, theater, Shakespeare and reading. At the young age of 6 years old, she danced for money and taught other children to dance. Dancing lessons took precedence over formal education; however, she read and was inspired by the works of Walt Whitman and Nietzsche.

ACCOMPLISHMENTS: Isadora is known as the mother of "modern dance," founding the "New System" of interpretive dance, blending together poetry, music and the rhythms of nature. She did not believe in the formality of conventional ballet and gave birth to a more free form of dance, dancing barefoot and in simple Greek apparel. Her fans recognized her for her passionate dancing and she ultimately proved to be the most famous dancer of her time.

In 1895 Isadora and her family moved east to pursue her professional dancing career. She opened In New York as a fairy with August Daly's company in A Midsummer Night's Dream. She was also funded by wealthy New Yorkers to give private appearances. In 1898 she expanded her dancing career by traveling to London on a cattle boat with her mother, her sister Elizabeth and brother, Raymond. Her first professional European performance was at the Lyceum theater in London on February 22, 1900. She turned down substantial dancing offers to join Loie Fuller's touring company and toured Budapest, Vienna, Munich and Berlin. She studied for one year in Greece where she purchased Kopanos Hill outside of Athens to construct an elaborate dancing stage. Her performances were based on interpretations of classical music including Strauss' Blue Danube, Chopin's Funeral March, Tchaikovsky's Symphonie Pathetique and Wagnerian works.

Later in her life she opened a dancing school in Moscow where the Russian government promised to provide her with room and board and a schoolroom. However, after the school was built the government did not support her. To support herself, she returned to the stage unsuccessfully in America and then toured Europe once more. She died in Europe.WRITINGS: Isadora's writings included The Dance, in 1909; My Life, her autobiography in 1927; various periodical articles on dancing; and The Art of the Dance a memorial volume published in 1928.

Born in 1878 in San Francisco, Isadora Duncan grew up in a childhood filled with imagination and art. Her mother introduced her four children (Isadora was youngest) to classical music, as well as Shakespeare, poetry, literature and art. Isadora spent many hours playing and dancing upon the beach, and even taught dance classes to younger children as a way to earn a little extra money for the struggling family.

In her teenage years, Isadora traveled to Chicago and New York with some of her family members, working and performing in various productions such as Mme. Pygmalion, Midsummer's Night Dream or vaudeville shows with limited success.

It was not until she reached London, however, that Isadora began to find acceptance for her dancing. She performed in private "salons" for ladies of social standing and their guests in London and Paris. Gradually her popularity grew, and she began performing on great stages throughout Europe.Throughout her career, Isadora had a driving vision for the education of young children, grounding their learning in art, culture, movement and spirituality as well as as traditional academic lessons. She began her first school in Grunewald, Germany in 1904, selecting children from the poorer classes and providing completely for all their physical and materials need from her own pocket.

The financial drain of her schools (schools were also established in Russia and Paris at various points in her life) forced Isadora to tour and perform considerably, leaving her sister Elizabeth in charge of the schools and pupils.

Though not a believer in what she saw as the chains of marriage, Isadora did have two children, Deidre and Patrick, with two of her lovers, Gordon Craig and Paris Singer. Tragically the two children drowned with their governess in the Seine river in 1913.

The following years were difficult for Isadora, and she stopped dancing for a time. Finally, however, she found a renewed artistic energy when she returned to her schools and her "foster" children, the school pupils. She even adopted six of those children, the "Isadorables" as they were billed by the press later when they began to perform with Isadora.

Tragically, Isadora's life was cut short in 1927 in a car accident along the Riveria. However, Isadora's spirit lives on through the tremendous influence she had, not only in dance, but on all art forms, in society and on cultural norms.

(1877-1927), dancer and choreographer. Born in San Francisco, Duncan grew up in a freethinking family headed by her mother, a follower of Robert Ingersoll. From the city's thriving Bohemia, Duncan absorbed the cult of nature, Hellenism, and belief in the semidivinity of the body that became tenets of her artistic credo. Other lasting influences were Delsartism, a system of movement that linked gestural expression with mental states, and the "new gymnastics," which stressed flexibility, coordination, and balance and was aligned with the feminist movements for dress and health reform.

After a brief stint in the commercial theater, Duncan embarked on a career as a solo concert artist, first in New York and then in Europe, where she arrived in 1900 and spent the better part of her life. In London and Paris, she created her first important dances, idylls rooted in Grecian themes and performed to composers like Mendelssohn, Gluck, and Chopin. She quickly found an audience among artists and intellectuals who appreciated her striking originality--her daring use of concert music, her open expression of physicality (enhanced by bare feet and body-revealing tunics), her creation of an idiom that owed nothing to the technique and tradition of ballet.

Although she occasionally choreographed for groups, her greatest works were solos she created for herself. Duncan was a charismatic performer, exceptionally musical and with a gift for coaxing emotion from pure movement and gesture. Her vocabulary was simple, but she had a magnificent sense of space and an intuitive understanding of its psychological organization. She knew the value of stillness and made a virtue of weight. Abandoning corsets, she discovered the "crater of motor power" in her articulate and liberated torso.

Duncan's personal life was as unconventional as her dancing. A believer in free love, she had numerous liaisons and bore her two children, by Gordon Craig and Paris Singer, out of wedlock. She spent money like water, running up bills others usually paid. Her politics, always radical, took a socialist turn during World War I when she discovered the poverty of New York's Lower East Side. In 1921, at the invitation of Anatoly Lunacharsky, the Soviet commissar of enlightenment, she went to Moscow, where she established a school and married the poet Sergei Essenin. Duncan's last American tour, in 1922-1923, was filled with scandal; in Boston, baring her breast and waving a red scarf, she cried, "This is red! So am I!" In 1927, it was a scarf, caught in the moving wheel of a flashy Bugatti, that broke her neck. Her lively, if not always accurate autobiography, Ma Vie, was published posthumously.

Although her art died with her, Duncan's influence on contemporaries was enormous. In Europe, especially, she set off a wave of "interpretative" dancers who flooded theaters, salons, and concert halls up to the 1930s. Ironically, in view of her loathing for the danse d'école, elements of her style were absorbed into the period's "new ballet." Regarded as a founding mother of American modern dance, she left to future generations a legacy of daring and unconventionality--art as an act of heroic self-creation.

Angela Isadora Duncan was born in 1877 in San Francisco, California. As a child she studied ballet, Delsarte technique and burlesque forms like skirt dancing. She began her professional career in Chicago in 1896, where she met the theatrical producer Augustin Daly. Soon after, Duncan joined his his touring company, appearing in roles ranging from one of the fairies in a "Mid-summer Night's Dream" to one of the quartet girls in "The Giesha." Duncan traveled to England with the Daly company in 1897. During this time she also danced as a solo performer at a number of society functions in and around London.

Returning to New York City in 1898, Duncan left the Daly company and began performing her solo dances at the homes of wealthy patrons. Calling their program "The Dance and Philosophy," Isadora and her older sister Elizabeth offered society women an afternoon of dance pieces set to Strauss waltzes and Omar Khayyam's "The Rubbaiyat." Influenced by the Americanized Delsarte movement, these "afternoons" received little serious notice from the press. Duncan became discouraged by the lack of enthusiasm, and, with her mother andsiblings, set sail for London in 1899.

In the years between 1899 and 1907, Duncan lived and worked in the great cities of Europe. In London in 1900 she met a group of artists and critics --led by the painter Charles Halle and the music critic John Fuller-Maitland -- who introduced her to Greek statue art, Italian Renaissance paintings and symphonic music. During this perioed, Fuller-Maitland convinced her to stop dancing to recitations and to begin using the music of Chopin and Beethoven for her inspiration.

In Germany Duncan was introduced to the philosopy of Frederick Nietzsche, and soon after began formulating her own philosophy of dance. In 1903 she delivered a speech in Berlin called "The Dance of the Future." In it she argued that the dance of the future would be similar to the dance of the ancient Greeks, natural and free. Duncan accused the ballet of "deforming the beautiful woman's body" and called for its abolition. She ended her speech by stating that "the dance of the future will have to become again a high religious art as it was with the Greeks. For art which is not religious is not art, is mere merchandise." It was during this period that Duncan began clarifying her theory of natural dance, identifying the source of the body's natural movement in the solar plexus.

Between 1904 and 1907, Duncan lived and worked in Greece, Germany, Russia and Scandanavia. During this period she worked with many famous artists, including the scenic designer Gordon Craig and the Russian theatre director Constantin Stanislavsky. In 1904, Duncan established her first school of dance in Grunewald, a suburb outside of Berlin. There, she began to develop her theories of dance education and to assemble her famous dance group, later known as the Isadorables.

Duncan returned to the United States in 1908 to begin a series of tours throughout the country. At first, her performances were poorly received by music critics, who felt that the dancer had no right to "interpret" symphonic music. The music critic from The New York Times, for example, wrote that there was "much question of the necessity or the possibility of a physical 'interpretation' of the symphony upon the stage...it seems like laying violent hands on a great masterpiece that had better be left alone." (1908). But the audiences grew more and more enthusiastic, and when Duncan returned to Europe in 1909, she was famous throughout the world. In the following years, Duncan created and maintained schools in France, Germany and Russia. She continued to sponsor young dancers and to give her solo performances. She returned to the United States several times, touring the country, but she never lived there again. In 1927, Duncan was killed in an automobile accident in Paris.

Isadora Duncan's Innovations:

1. Duncan was the first American dancer to develop and label a concept of natural breathing, which she identified with the ebb and flow of ocean waves.

2. Duncan was the first American dancer to define movement based on natural and spiritual laws rather than on formal considerations of geometric space.

3. Duncan was the first American dancer to rigorously compare dance to the other arts, defending it as a primary art form worthy of "high art" status.

4. Duncan was the first American dancer to develop a philosophy of the dance.

5. Duncan was the first American dancer to deemphasize scenery and costumes in favor of a simple stage setting and simple costumes. By doing this, Duncan suggested that watching a dancer dance was enough.