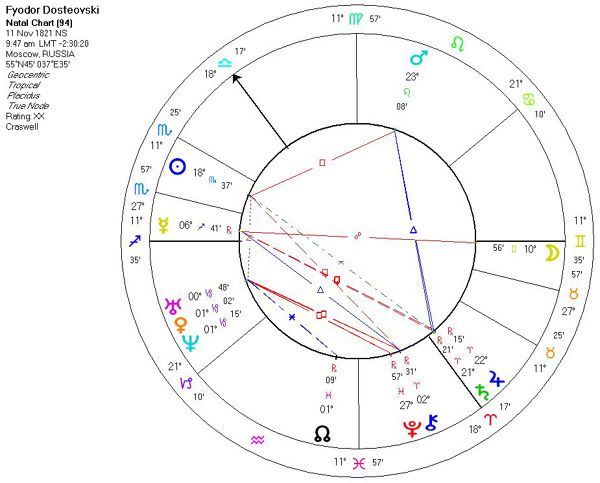

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

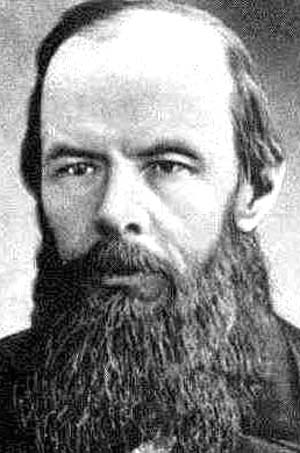

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

Beauty is mysterious as well as terrible. God and devil are fighting there, and the battlefield is the heart of man.

Deprived of meaningful work, men and women lose their reason for existence; they go stark, raving mad.

Happiness does not lie in happiness, but in the achievement of it.

If there is no God, everything is permitted.

Innovators and men of genius have almost always been regarded as fools at the beginning (and very often at the end) of their careers.

It is not possible to eat me without insisting that I sing praises of my devourer?

It seems, in fact, as though the second half of a man's life is made up of nothing but the habits he has accumulated during the first half.

Man is fond of counting his troubles, but he does not count his joys. If he counted them up as he ought to, he would see that every lot has enough happiness provided for it.

Much unhappiness has come into the world because of bewilderment and things left unsaid.

(Mercury conjunct Ascendant opposition Moon in Gemini on Descendant.)One can know a man from his laugh, and if you like a man's laugh before you know anything of him, you may confidently say that he is a good man.

Realists do not fear the results of their study.

Sarcasm: the last refuge of modest and chaste-souled people when the privacy of their soul is coarsely and intrusively invaded.

The formula 'Two and two make five' is not without its attractions.

The greatest happiness is to know the source of unhappiness.

The soul is healed by being with children.

There are things which a man is afraid to tell even to himself, and every decent man has a number of such things stored away in his mind.

There is no subject so old that something new cannot be said about it.

To live without Hope is to Cease to live.

We sometimes encounter people, even perfect strangers, who begin to interest us at first sight, somehow suddenly, all at once, before a word has been spoken.

The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.

(Scorpio on the cusp of the 12th house.)Without some goal and some effort to reach it, no man can live.

Man is unhappy because he doesn't know he's happy. . . . If anyone finds out he'll become happy at once.

The secret of man's being is not only to live but to have something to live for.

It would be interesting to know what it is men are most afraid of. Taking a new step, uttering a new word.

Man has such a predilection for systems and abstract deductions that he is ready to distort the truth intentionally, he is ready to deny the evidence of his senses only to justify his logic.

You are told a lot about your education, but some beautiful, sacred memory, preserved since childhood, is perhaps the best education of all. If a man carries many such memories into life with him, he is saved for the rest of his days. And even if only one good memory is left in our hearts, it may also be the instrument of our salvation one day.

The trouble with children is that they are not returnable.

"I think if the devil doesn't exist, then man has created him. He has created him in his own image and likeness." "Just as man created God, then?" observed Alyosha.

It is not the brains that matter most, but that which guides them - the character, the heart, generous qualities, progressive ideas.

Man is tormented by no greater anxiety than to find someone quickly to whom he can hand over that great gift of freedom with which the ill-fated creature is born.

If you want to be respected by others the great thing is to respect yourself. Only by that, only by self-respect will you compel others to respect you.

Neither man or nation can exist without a sublime idea.

Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him.

It's in the homes of spiteful old widows that one finds such cleanliness.

There is nothing easier than lopping off heads and nothing harder than developing ideas.

I utter what you would not dare think.

To live without Hope is to Cease to live.

Man has such a predilection for systems and abstract deductions that he is ready to distort the truth intentionally, he is ready to deny the evidence of his senses only to justify his logic.

There are moments, you reach moments, when all of a sudden time stops and becomes eternal.

Love all that has been created by God, both the whole and every grain of sand. Love every leaf and every ray of light. Love the beasts and the birds, love the plants, love every separate fragment. If you love each fragment, you will understand the mystery of the whole resting in God.

It is easier for a Russian to become an atheist than for anyone else in the world.

"I like them to talk nonsense. That's man's one privilege over all creation. Through error you come to the truth! I am a man because I err! You never reach any truth without making fourteen mistakes and very likely a hundred and fourteen." Crime and Punishment

(Sagittarius Ascendant)"If he has a conscience he will suffer for his mistake. That will be his punishment--as well as the prison." Crime and Punishment

"To go wrong in one's own way is better than to go right in someone else's." Crime and Punishment

(Mars in Leo)They wanted to speak, but could not; tears stood in their eyes. They were both pale and thin; but those sick pale faces were bright with the dawn of a new future, of a full resurrection into a new life. They were renewed by love; the heart of each held infinite sources of life for the heart of the other. Crime and Punishment

Man is sometimes extraordinarily, passionately, in love with suffering . . . Notes from the Underground

But yet I am firmly persuaded that a great deal of consciousness, every sort of consciousness, in fact, is a disease. Notes from the Underground

There is no virtue if there is no immortality.

(Scorpio Sun)If they drive God from the earth, we shall shelter Him underground.

- The Brothers KaramazovIs there suffering on this new earth? On our earth we can truly love only with suffering and through suffering! We know not how to love otherwise. We know no other love. I want suffering in order to love.

Dream of a Ridiculous Man

(Saturn conjunct Jupiter)Indeed, in our country, and in all classes, there are, and always will be, strange easy-going people whose destiny it is to remain always beggars. They are poor devils all their lives; quite broken down, they remain under the domination or guardianship of some one, generally a prodigal, or a man who has suddenly made his fortune. All initiative is for them an insupportable burden. They only exist on condition of undertaking nothing for themselves, and by serving, always living under the will of another. They are destined to act by and through others. Under no circumstances, even of the most unexpected kind, can they get rich; they are always beggars. I have met these persons in all classes of society, in all coteries, in all associations, including the literary world.

- The House of the Dead...to be acutely conscious is a disease, a real, honest-to-goodness disease.

- Notes from the UndergroundEvery man has some reminiscences which he would not tell to everyone, but only to his friends. He has others which he would not reveal even to his friends, but only to himself, and that in secret. But finally there are still others which a man is even afraid to tell himself, and every decent man has a considerable number of such things stored away. That is, one can even say that the more decent he is, the greater the number of such things in his mind.

Notes from the Underground

(Scorpio Sun)It's a burden for us even to be men- men with real, our own bodies and blood; we're ashamed of it, we consider it a disgrace, and keep trying to be some unprecedented omni-men. We're stillborn, and have long ceased to be born of living fathers, and we like this more and more. We're acquiring a taste for it. Soon we'll contrive to be born somehow from an idea. But enough; I don't want to write any more "from Underground."

- Notes from the Underground"If there is no God, then I am God."

- The Possessed or Demons"But you're a poet, and I'm a simple mortal, and therefore I will say one must look at things from the simplest, most practical point of view. I, for one, have long since freed myself from all shackles, and even obligations. I only recognize obligations when I see I have something to gain by them. You, of course, can't look at things like that, your legs are in fetters and your taste is morbid. You yearn for the ideal, for virtue. But, my dear friend, I am ready to recognize anything you tell me to, but what shall I do if I know for a fact that at the root of all human virtues lies the most intense egoism?"

Born: November 11, 1821

Died: February 9, 1881

Occupation(s): Novelist

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky

Fëdor Mihajlovic Dostoevskij, sometimes transliterated Dostoyevsky listen is considered one of the greatest Russian writers. His works have had a profound and lasting effect on twentieth-century fiction.Dostoevsky's novels often feature characters living in poor conditions with disparate and extreme states of mind, and explore human psychology while analysing the political, social and spiritual states of the Russia of his time. He is sometimes considered to be a founder of existentialism, most frequently for Notes from Underground, which has been described by Walter Kaufmann as "the best overture for existentialism ever written."

Early life

Dostoevsky was the second of seven children born to Mikhail and Maria Dostoevsky. The family originated from the Polish Szlachta family Dostojewski Radwan Coat of Arms.Dostoevsky's father was a retired military surgeon and a violent alcoholic, who served as a doctor at the Mariinsky Hospital for the Poor in Moscow. The hospital was situated in one of the worst areas in Moscow. Local landmarks included a cemetery for criminals, a lunatic asylum, and an orphanage for abandoned infants. This urban landscape made a lasting impression on the young Dostoevsky, whose interests in and compassion for the poor and oppressed tormented him. Though his parents forbade it, Dostoevsky liked to wander out to the hospital garden, where the suffering patients sat to catch a glimpse of sun. The young Dostoevsky loved to spend time with these patients and hear their stories.

There are many stories of Dostoevsky's father's despotic treatment of his children. After returning home from work, he would take a nap and his children, ordered to keep absolutely silent, stood silently by their slumbering father in shifts and swatted flies around his head.

Shortly after his mother died of tuberculosis in 1837, Dostoevsky and his brother were sent to the Military Engineering Academy at St Petersburg. Mikhail Dostoevsky, too, died in 1839. Though it has never been proven, it is widely believed that he was murdered by his own serfs. Reportedly, they became enraged during one of his drunken fits of violence, restrained him, and poured vodka into his mouth until he drowned. Another story holds that Mikhail died of natural causes, and a neighboring landowner invented the story of his murder so that he might buy the estate inexpensively. The figure of his domineering father would exert a large effect upon Dostoevsky's work, and is notably seen through the character of Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov, the "wicked and sentimental buffoon" father of the three main characters in his 1881 novel The Brothers Karamazov.

At the St Petersburg Academy of Military Engineering, Dostoevsky was taught mathematics, a subject he despised. However, he also studied literature by Shakespeare, Pascal, Victor Hugo and E.T.A. Hoffmann. Though he focussed on different areas to mathematics, he did well on the exams and received a commission in 1841. That year, he is known to have written two romantic plays, influenced by the German Romantic poet/playwright Friedrich Schiller: Mary Stuart and Boris Godunov. The plays have not been preserved. Though Dostoevsky, a self-described "dreamer" as a young man, at the time revered Schiller, in the years which yielded his great masterpieces he usually poked fun at him.

Beginnings of a literary career

Dostoevsky was made a lieutenant in 1842, and left the Engineering Academy the following year. He completed a translation into Russian of Balzac's novel Eugenie Grandet in 1843, but it brought him little or no attention. Dostoevsky started to write his own fiction in late 1844 after leaving the army. In 1845, his first work, the epistolary short novel, Poor Folk, published in the periodical "The Contemporary", was met with great acclaim. The editor of the magazine, the poet Nikolai Nekrasov, walked into the office of the liberal critic Vissarion Belinsky, and announced: "A new Gogol has arisen!" Belinsky, his followers and many others agreed and after the novel was fully published in book form at the beginning of the next year, Dostoevsky became a literary celebrity at the age of 24.In 1846, Belinsky and many others reacted negatively to his novella, The Double, a psychological study of a bureaucrat whose alter ego overtakes his life. Dostoevsky's fame began to cool. Much of his work after Poor Folk was met with mixed reviews and it seemed that Belinsky's prediction that Dostoevsky would be one of the greatest writers of Russia was mistaken.

Exile in Siberia

Monument to Dostoevsky in Omsk, his place of exileDostoevsky was arrested and imprisoned on April 23, 1849 for engaging in revolutionary activity against Tsar Nicholas I. On November 16 that year he was sentenced to death for anti-government activities linked to a liberal intellectual group, the Petrashevsky Circle. After a mock execution, in which he and other members of the group stood outside in freezing weather waiting to be shot by a firing squad, Dostoevsky's sentence was commuted to four years of exile with hard labor at a katorga prison camp in Omsk, Siberia. Dostoevsky described later to his brother the sufferings he went through as the years in which he was "shut up in a coffin." Describing the dilapidated barracks which, as he put in his own words, "should have been torn down years ago", he wrote:"In summer, intolerable closeness; in winter, unendurable cold. All the floors were rotten. Filth on the floors an inch thick; one could slip and fall...We were packed like herrings in a barrel...There was no room to turn around. From dusk to dawn it was impossible not to behave like pigs...Fleas, lice, and black beetles by the bushel..."[1]

His first recorded epileptic seizure occurred in 1850 at the prison camp. It is said that he suffered from a rare form of temporal lobe epilepsy, sometimes referred to as "ecstatic epilepsy".[citation needed] It is also said that upon learning of his father's death before the elder could reply to a letter of criticism from Fyodor, the younger Dostoevsky experienced his first seizure.

Seizures recurred sporadically throughout his life, and Dostoevsky's experiences are thought to have formed the basis for his description of Prince Myshkin's epilepsy in the The Idiot. He was released from prison in 1854, and was required to serve in the Siberian Regiment. Dostoevsky spent the following five years as a private (and later lieutenant) in the Regiment's Seventh Line Battalion, stationed at the fortress of Semipalatinsk, now in Kazakhstan. While there, he began a relationship with Maria Dmitrievna Isaeva, the wife of an acquaintance in Siberia. They married in February 1857, after her husband's death.

Dostoevsky's experiences in prison and the army resulted in major changes in his political and religious convictions. He became disillusioned with 'Western' ideas, and began to pay greater tribute to traditional Russian values. Perhaps most significantly, he had what his biographer Joseph Frank describes as a conversion experience in prison, which greatly strengthened his Christian, and specifically Orthodox, faith (the experience is depicted by Dostoevsky in The Peasant Marey (1876)). In line with his new beliefs, Dostoevsky became a sharp critic of the Nihilist and Socialist movements of his day, and he dedicated his book The Possessed and his The Diary of a Writer to espousing conservatism and criticizing socialist ideas [1]. He later formed a friendship with the conservative statesman Konstantin Pobedonostsev.

Later literary career

In December 1859, Dostoevsky returned to St Petersburg, where he ran a series of unsuccessful literary journals, Vremya (Time) and Epokha (Epoch), with his older brother Mikhail. The latter had to be shut down as a consequence of its coverage of the Polish Uprising of 1863. That year Dostoevsky traveled to Europe and frequented the gambling casinos. There he met Apollinaria Suslova, the model for Dostoesvky's "proud women", such as Katerina Ivanovna in both Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov.Dostoevsky was devastated by his wife's death in 1864, followed shortly thereafter by his brother's death. He was financially crippled by business debts and the need to provide for his wife's son from her earlier marriage and his brother's widow and children. Dostoevsky sank into a deep depression, frequenting gambling parlors and accumulating massive losses at the tables.

Dostoevsky suffered from an acute gambling compulsion as well as from its consequences. By one account Crime and Punishment, possibly his best known novel, was completed in a mad hurry because Dostoevsky was in urgent need of an advance from his publisher. He had been left practically penniless after a gambling spree. Dostoevsky wrote The Gambler simultaneously in order to satisfy an agreement with his publisher Stellovsky who, if he did not receive a new work, would have claimed the copyrights to all of Dostoevsky's writing.

Motivated by the dual wish to escape his creditors at home and to visit the casinos abroad, Dostoevsky traveled to Western Europe. There, he attempted to rekindle a love affair with Suslova, but she refused his marriage proposal. Dostoevsky was heartbroken, but soon met Anna Grigorevna Snitkina, a twenty-year-old stenographer. Shortly before marrying her in 1867, he dictated The Gambler to her. This period resulted in the writing of what are generally considered to be his greatest books. From 1873 to 1881 he published the Writer's Diary, a monthly journal full of short stories, sketches, and articles on current events. The journal was an enormous success.

Dostoevsky is also known to have influenced and been influenced by the philosopher Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov. Solovyov is noted as the inspiration for the character Alyosha Karamazov. [2]

In 1877, Dostoevsky gave the keynote eulogy at the funeral of his friend, the poet Nekrasov, to much controversy. In 1880, shortly before he died, he gave his famous Pushkin speech at the unveiling of the Pushkin monument in Moscow. From that event on, Dostoevsky was acclaimed all over Russia as one of her greatest writers and hailed as a prophet, almost a mystic.

In his later years, lived for a long time at the resort of Staraya Russa, which was closer to St Petersburg and less expensive than German resorts. He died on February 9 (January 28 O.S.), 1881 of a lung hemorrhage associated with emphysema and an epileptic seizure. He was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, St Petersburg, Russia. Forty thousand mourners attended his funeral.1 His tombstone reads "Verily, Verily, I say unto you, Except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit." from John 12:24, which is also the epigraph of his final novel, The Brothers Karamazov.

Dostoyevsky is considered one of the greatest writers in world literature. Best-known for his novels Prestupleniye i nakazaniye (1866; Crime and Punishment) and Bratya Karamazovy (1880; The Brothers Karamazov), he attained profound philosophical and psychological insights which anticipated important developments in twentieth-century thought, including psychoanalysis and existentialism. In addition, Dostoyevsky's powerful literary depictions of the human condition exerted a profound influence on modern writers, such as Franz Kafka, whose works further develop some of the Russian novelist's themes. The writer's own troubled life enabled him to portray with deep sympathy characters who are emotionally and spiritually downtrodden and who in many cases epitomize the traditional Christian conflict between the body and the spirit.

Dostoyevsky grew up in a middle-class family in Moscow. His father, a doctor, was a tyrant toward his family, and his mother was a mild, pious woman who died before Dostoyevsky was sixteen. Partly to escape the oppressive atmosphere of his father's household, the boy acquired a love of reading, especially the works of Nikolai Gogol, E. T. A. Hoffmann, and Honore de Balzac. At his father's insistence, Dostoyevsky trained as an engineer in St. Petersburg. While the youth was at school, his father was murdered by his own serfs at the family's small country estate. Dostoyevsky rarely mentioned his father's murder, but Oedipal themes are recurrent in his work, and Sigmund Freud suggested that the novelist's epilepsy was a manifestation of guilt over his repressed wish for his father's death.

Dostoyevsky graduated from engineering school but chose a literary career. His first published work, a translation of Balzac's novel Eugenie Grandet, appeared in a St. Petersburg journal in 1844. Two years later, he published his first novel, Bednye lyudi (1846;Poor Folk), a naturalistic tale with a clear social message as well as a delicate description of life's tragic aspects as manifested in everyday existence. The twenty-four-year-old author became an overnight celebrity when Vissarion Belinsky, the most influential critic of the day, praised Dostoyevsky for his social awareness and declared him the literary successor of Gogol. Dostoyevsky joined Belinsky's literary circle but later broke with it when the critic reacted coldly to his subsequent works. Belinsky judged the novel Dvoynik (1846;The Double) and the short stories Gospodin Prokharchin (1846;Mr. Prokharchin) and Khozyayka (1847; The Landlady) as devoid of a social message.

In 1848 Dostoyevsky joined a group of young intellectuals, led by Mikhail Petrashevsky, which met to discuss literary and political issues. In the reactionary political climate of mid-nineteenth-century Russia, such groups were illegal, and in 1849 the members of the so-called Petrashevsky Circle were arrested and charged with subversion. Dostoyevsky and several of his associates were imprisoned and sentenced to death. As they were facing the firing squad, an imperial messenger arrived with the announcement that the Czar had commuted the death sentences to hard labor in Siberia. This scene was to haunt the novelist the rest of his life. Dostoyevsky described his life as a prisoner in Zapiski iz myortvogo doma (1862; The House of the Dead), a novel demonstrating both an insight into the criminal mind and an understanding of the Russian lower classes. While in prison the writer underwent a profound spiritual and philosophical transformation. His intense study of the New Testament, the only book the prisoners were allowed to read, contributed to his rejection of his earlier liberal political views and led him to the conviction that redemption is possible only through suffering and faith, a belief which informed his later work.

Dostoyevsky was released from the prison camp in 1854; however, he was forced to serve as a soldier in a Siberian garrison for an additional five years. When Dostoyevsky was finally allowed to return to St. Petersburg in 1859, he eagerly resumed his literary career, founding two periodicals and writings articles and short fiction. The articles expressed his new-found belief in a social and political order based on the spiritual values of the Russian people. These years were marked by further personal and professional misfortunes, including the forced closing of his journals by the authorities, the deaths of his wife and his brother, and a financially devastating addiction to gambling. It was in this atmosphere that Dostoyevsky wrote Zapiski iz podpolya (1864; Notes from the Underground) and Crime and Punishment. In Notes from the Underground Dostoyevsky satirizes contemporary social and political views by presenting a narrator whose notes reveal that his purportedly progressive beliefs lead only to sterility and inaction. Dostoyevsky's portrayal of this bitter and frustrated Underground Man is hailed as the introduction of an important new type of literary figure. Crime and Punishment brought him acclaim but scant financial compensation. Viewed by critics as one of his masterpieces, Crime and Punishment is the novel in which Dostoyevsky first develops the theme of redemption through suffering. The protagonist Raskolnikovwhose name derives from the Russian word for schism or splitis presented as the embodiment of spiritual nihilism. The novel depicts the harrowing confrontation between his philosophical beliefs, which prompt him to commit a murder in an attempt to prove his supposed superiority, and his inherent morality, which condemns his actions.

In 1867, Dostoyevsky fled to Europe with his second wife to escape creditors. Although they were distressing due to financial and personal difficulties, Dostoyevsky's years abroad were fruitful, for he completed one important novel and began another. Idiot (1869; The Idiot), influenced by Hans Holbein's painting Christ Taken from the Cross and by Dostoyevsky's opposition to the growing atheistic sentiment of the times, depicts the Christ-like protagonist's loss of innocence and his experience of sin. Dostoyevsky's profound conservatism, which marked his political thinking following his Siberian experience, and especially his reaction against revolutionary socialism, provided the impetus for his great political novel Besy (1871-72; The Possessed). Based on a true event, in which a young revolutionary was murdered by his comrades, this novel provoked a storm of controversy for its harsh depiction of ruthless radicals. In his striking portrayal of Stavrogin, the novel's central character, Dostoyevsky described a man dominated by the life-denying forces of nihilism.

Dostoyevsky returned to Russia in 1871 and began his final decade of prodigious literary activity. In sympathy with the conservative political party, he accepted the editorship of a reactionary weekly, Grazhdanin (The Citizen). In his Dnevnik pisatelya (1873-1877; The Diary of a Writer), initially a column in the Citizen but later an independent periodical, Dostoyevsky published a variety of prose works, including some of his outstanding short stories. Dostoyevski's last work was Bratya Karamazovy (1880; The Brothers Karamazov), a family tragedy of epic proportions, which is viewed as one of the great novels of world literature. The novel recounts the murder of a father by one of his four sons. Initially, his son Dmitri is arrested for the crime, but as the story unfolds it is revealed that the illegitimate son Smerdyakov has killed the old man at what he believes to be the instigation of his half-brother Ivan. Ivan's philosophical essay, The Legend of the Grand Inquisitor, is a work now famous in its own right. Presented as a debate in which the Inquisitor condemns Christ for promoting the belief that mankind has the freedom of choice between good and evil, the piece explores the conflict between intellect and faith, and between the forces of evil and the redemptive power of Christianity. Dostoyevsky envisioned this novel as the first of a series of works depicting The Life of a Great Sinner, but early in 1881, a few months after completing The Brothers Karamazov, the writer died at his home in St. Petersburg.

To his contemporary readers, Dostoyevsky appeared as a writer primarily interested in the terrible aspects of human existence. However, later critics have recognized that the novelist sought to plumb the depths of the psyche, in order to reveal the full range of the human experience, from the basest desires to the most elevated spiritual yearnings. Above all, he illustrated the universal human struggle to understand God and self. Dostoyevsky was, Katherine Mansfield wrote, a being who loved, in spite of everything, adored life, even while he knew the dank, dark places.