Augustus Caesar

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

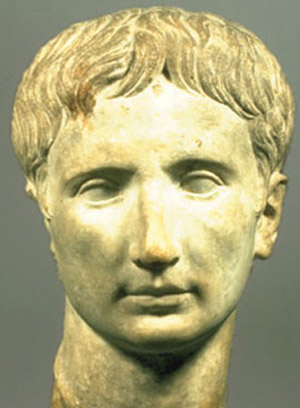

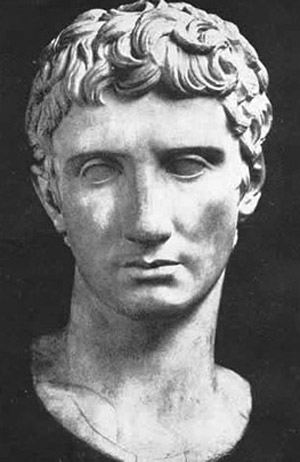

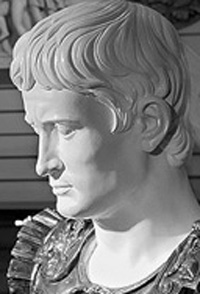

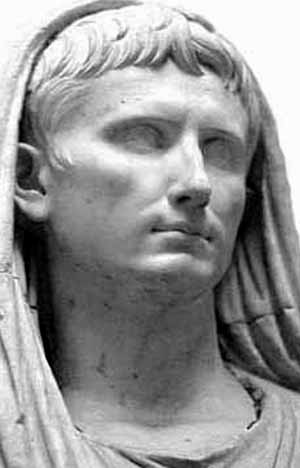

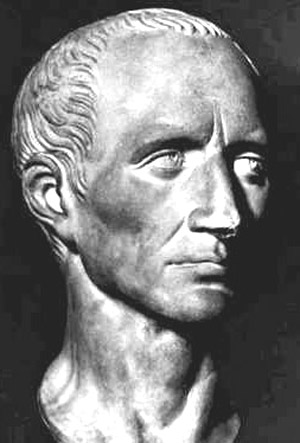

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

Augustus Caesar

—Roman Emperor

(62 B.C. – 14 A.D.) September 21, 62 B.C., NS, Rome, Italy, 5:35 AM, LMT (Source: LMR cites Fagan who, in American Astrology, 1969 quotes the historian Sutonius, Lives of a Dozen Caesars ) Planetary positions vary depending upon which program is used to calculate B.C. positions. Died, Aug. 19, AD 14, Nola, near Naples

An alternative time is given by the Encyclopedia Britannica: September 23, 63 BC. Marc Penfield give September 22, 63 BC.

(Ascendant, Virgo with Sun in Virgo rising, with Mercury also in Virgo; MC, Gemini with Pluto also in Gemini; Uranus and Neptune in Cancer conjunct, with Jupiter also in Cancer’ Moon in Capricorn; Venus in Scorpio; Mars conjunct Saturn and the NN in Taurus’)

However, according to LMR in The American Book of Charts, while Sun, Mercury and Ascendant are in Virgo, Moon is in Capricorn; Mars is in Taurus with the NN; Venus is in Scorpio; Jupiter is in Cancer)

This discrepancy can be solved by noticing that the Rodden Chart, though stating 62 BC, is calculated for 63 BC and not 62 BC.

The charts for the 22nd, (Penfield) and the 23rd (Britannica) yield an Aquarius Moon. That is the only significant difference.

Grandson of Julius Caesar. A cold, calculating statesman who knew how to win popular affection. Became Emperor in 27BC. During his lifetime Rome reached its greatest glory, a golden age of literature and architecture. Mention the presence of R7 and R3.

After this time I surpassed all others in authority, but I had no more power than the others who were also my colleagues in office.

I found Rome a city of bricks and left it a city of marble.

More haste, less speed. -Festina lente

Also quoted as: Make haste slowly.Well done is quickly done.

You cheer my heart, who build as if Rome would be eternal.

Source: to Piso, see Plutarch "Apothegms"Nothing common can seem worthy of you.

The play is over. Acta est fabula

Last Words

Augustus

Emperor of the Roman Empire

Reign: January 16, 27 BC - August 19 14 AD

Predecessor Julius Caesar (as Dictator)

Consort 1) Clodia Pulchra ? – 40 BC

2) Scribonia 40 BC – 38 BC

3) Livia Drusilla 38 BC to 14 AD

Issue Julia the ElderBorn September 23, 63 BC Rome

Died August 19, AD 14 Nola

Children Natural - Julia the Elder

Adoptive - Gaius Caesar, Lucius Caesar, Agrippa Postumus, TiberiusAugustus (Latin: IMPERATOR CAESAR DIVI FILIVS AVGVSTVS;[1] September 23, 63 BC – August 19, AD 14), known as Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (in English Octavian) for the period of his life prior to 27 BC, was the first and among the most important of the Roman Emperors.

Although he preserved the outward form of the Roman Republic, he ruled as an autocrat for more than 40 years and his rule is the dividing line between the Republic and the Roman Empire. He ended a century of civil wars and gave Rome an era of peace, prosperity, and imperial greatness, known as the Pax Romana, Roman peace.

He was born in Rome (or Velletri) on September 23, 63 BC with the name Gaius Octavius. His father, also Gaius Octavius, came from a respectable but undistinguished family of the equestrian order and was governor of Macedonia. Shortly after Octavius's birth, his father gave him the surname of Thurinus, possibly to commemorate his victory at Thurii over a rebellious band of slaves. His mother, Atia, was the niece of Julius Caesar, soon to be Rome's most successful general and Dictator. He spent his early years in his grandfather's house near Veletrae (modern Velletri). In 58 BC, when he was four years old, his father died. He spent most of his childhood in the house of his stepfather, Lucius Marcius Philippus.

In 51 BC, aged eleven, Octavius delivered the funeral oration for his grandmother Julia, elder sister of Caesar. He donned the toga virilis at fifteen, and was elected to the College of Pontiffs. Caesar requested that Octavius join his staff for his campaign in Africa, but Atia protested that he was too young. The following year, 46 BC, she consented for him to join Caesar in Hispania, but he fell ill and was unable to travel. When he had recovered, he sailed to the front, but was shipwrecked; after coming ashore with a handful of companions, he made it across hostile territory to Caesar's camp, which impressed his great-uncle considerably. Caesar and Octavius returned home in the same carriage, and Caesar secretly changed his will.

Bronze statue of Augustus, Archaeological Museum, Athens.When Caesar was assassinated on the Ides of March (the 15th) 44 BC, Octavius was studying in Apollonia, Illyria. When Caesar's will was read it revealed that, having no legitimate children, he had adopted his great-nephew Octavius as his son and main heir. By virtue of his adoption, Octavius assumed the name Gaius Julius Caesar. Roman tradition dictated that he also append the surname Octavianus (Octavian) to indicate his biological family; however, no evidence exists that he ever used that name. Mark Antony later charged that he had earned his adoption by Caesar through sexual favours, though Suetonius describes Antony's accusation as political slander.[2]

Octavian recruited a small force in Apollonia. Crossing over to Italia, he bolstered his personal forces with Caesar's veteran legionaries, gathering support by emphasizing his status as heir to Caesar. Only eighteen years old, he was consistently underestimated by his rivals for power.

In Rome, he found Mark Antony and the Optimates led by Marcus Tullius Cicero in an uneasy truce. After a tense standoff, and a war in Cisalpine Gaul after Antony tried to take control of the province from Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, he formed an alliance with Mark Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, Caesar's principal colleagues. The three formed a junta called the Second Triumvirate, an explicit grant of special powers lasting five years and supported by law, unlike the unofficial First Triumvirate of Gnaeus Pompey Magnus, Caesar and Marcus Licinius Crassus.[3]

The triumvirs then set in motion proscriptions in which 300 senators and 2,000 equites were deprived of their property and, for those who failed to escape, their lives, going beyond a simple purge of those allied with the assassins, and probably motivated by a need to raise money to pay their troops.[4]

Antony and Octavian then marched against Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius, who had fled to the east. After two battles at Philippi in Macedonia, the Caesarian army was victorious and Brutus and Cassius committed suicide (42 BC). After the battle, a new arrangement was made between the members of the Second Triumvirate: while Octavian returned to Rome, Antony went to Egypt where he allied himself with Queen Cleopatra VII, the former lover of Julius Caesar and mother of Caesar's infant son, Caesarion. Lepidus, now clearly marked as an unequal partner, settled for the province of Africa.

While in Egypt, Antony had an affair with Cleopatra that resulted in the birth of three children, Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene, and Ptolemy Philadelphus. Antony later left Cleopatra to make a strategic marriage with Octavian's sister, Octavia, in 40 BC. During their marriage Octavia gave birth to two daughters, both named Antonia. In 37 BC Antony deserted Octavia and went back to Egypt to be with Cleopatra. The Roman dominions were then divided between Octavian in the West and Antony in the East.

Antony occupied himself with military campaigns in the East and a romantic affair with Cleopatra; Octavian built a network of allies in Rome, consolidated his power, and spread propaganda implying that Antony was becoming less than Roman because of his preoccupation with Egyptian affairs and traditions. The situation grew more and more tense, and finally, in 32 BC, the senate officially declared war on "the Foreign Queen", to avoid the stigma of yet another civil war. It was quickly decided: in the bay of Actium on the western coast of Greece, after Antony's men began deserting, the fleets met in a great battle in which many ships burned and thousands on both sides lost their lives. Octavian defeated his rivals who then fled to Egypt. He pursued them, and after another defeat, Antony committed suicide.

Cleopatra also committed suicide after her upcoming role in Octavian's Triumph was "carefully explained to her", and Caesarion was "butchered without compunction". Octavian supposedly said "two Caesars are one too many" as he ordered Caesarion's death.[5] This demonstrates a key difference between Julius Caesar and Octavian--while Caesar had demonstrated clemency in his victories, Octavian most certainly did not.

Augustus as a magistrate.The Western half of the Roman Republic territory had sworn allegiance to Octavian prior to Actium in 31 BC, and after Actium and the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra, the Eastern half followed suit, placing Octavian in the position of ruler of the Republic. Years of civil war had left Rome in a state of near-lawlessness, but the Republic was not prepared to accept the control of Octavian as a despot.

At the same time, Octavian could not simply give up his authority without risking further civil wars amongst the Roman generals, and even if he desired no position of authority whatsoever, his position demanded that he look to the well-being of the City and provinces. Disbanding his personal forces, Octavian held elections and took up the position of consul; as such, though he had given up his personal armies, he was now legally in command of the legions of Rome.

In 27 BC, Octavian officially returned power to the Roman Senate, and offered to relinquish his own military supremacy over Egypt.

Reportedly, the suggestion of Octavian's stepping down as consul led to rioting amongst the Plebeians in Rome. A compromise was reached between the Senate and Octavian's supporters, known as the First Settlement. Octavian was given proconsular authority over the Western half and Syria — the provinces that, combined, contained almost 70% of the Roman legions.

The Senate also gave him the titles Augustus and Princeps. Augustus was a title of religious rather than political authority. In the mindset of contemporary religious beliefs, it would have cleverly symbolized a stamp of authority over humanity that went beyond any constitutional definition of his status. Additionally, after the harsh methods employed in consolidating his control, the change in name would also serve to separate his benign reign as Augustus from his reign of terror as Octavian. Princeps translates to "first-citizen" or "first-leader". It had been a title under the Republic for those who had served the state well; for example, Pompey had held the title.

In addition, and perhaps the most dangerous innovation, Augustus was granted the right to wear the Civic Crown of laurel and oak. This crown was usually held above the head of a Roman general during a Triumph, with the individual holding the crown charged to continually repeat, "Remember, thou art mortal," to the triumphant general. The fact that not only was Augustus awarded this crown but awarded the right to actually wear it upon his head is perhaps the clearest indication of the creation of a monarchy. However, it must be noted that none of these titles, or the Civic Crown, granted Octavian any additional powers or authority; for all intents and purposes the new Augustus was simply a highly-honored Roman citizen, holding the consulship.

These actions were highly abnormal from the Roman Senate, but this was not the same body of patricians that had murdered Caesar. Both Antony and Octavian had purged the Senate of suspect elements and planted it with their loyal partisans. How free a hand the Senate had in these transactions, and what backroom deals were made, remain unknown.

The second settlement

In 23 BC, Augustus renounced the consulship, but retained his consular imperium, leading to a second compromise between Augustus and the Senate known as the Second Settlement. Augustus was granted the power of a tribune (tribunicia potestas), though not the title, which allowed him to convene the Senate and people at will and lay business before it, veto the actions of either the Assembly or the Senate, preside over elections, and the right to speak first at any meeting.Also included in Augustus' tribunician authority were powers usually reserved for the Roman censor; these included the right to supervise public morals and scrutinize laws to ensure they were in the public interest, as well as the ability to hold a census and determine the membership of the Senate. No Tribune of Rome ever had these powers, and there was no precedent within the Roman system for combining the powers of the Tribune and the Censor into a single position, nor was Augustus ever elected to the office of Censor. Whether censorial powers were granted to Augustus as part of his tribunician authority, or he simply assumed these responsibilities, is still a matter of debate.

In addition to tribunician authority, Augustus was granted sole imperium within the city of Rome itself: all armed forces in the city, formerly under the control of the Praefects, were now under the sole authority of Augustus. Additionally, Augustus was granted imperium proconsulare maius, or "imperium over all the proconsuls", which translated to the right to interfere in any province and override the decisions of any governor. With maius imperium, Augustus was the only individual able to receive a triumph as he was ostensibly the head of every Roman army.

Many of the political subtleties of the Second Settlement seem to have evaded the comprehension of the Plebeian class. When, in 22 BC, Augustus failed to stand for election as consul, fears arose once again that Augustus, seen as the great "defender of the people", was being forced from power by the aristocratic Senate. In 22, 21, and 20 BC, the people rioted in response, and only allowed a single consul to be elected for each of those years, ostensibly to leave the other position open for Augustus. Finally, in 19 BC, the Senate voted to allow Augustus to wear the consul's insignia in public and before the Senate, with an act sometimes known as the Third Settlement. This seems to have assuaged the populace; regardless of whether or not Augustus was actually a consul, the importance was that he appeared as one before the people.

With these powers in mind, it must be understood that all forms of permanent and legal power within Rome officially lay with the Senate and the people; Augustus was given extraordinary powers, but only as a pronconsul and magistrate under the authority of the Senate. Augustus never presented himself as a king or autocrat, once again only allowing himself to be addressed by the title princeps. After the death of Lepidus in 13 BC, he additionally took up the position of pontifex maximus, the high priest of the collegium of the Pontifices, the most important position in Roman religion.

Later Roman Emperors would generally be limited to the powers and titles originally granted to Augustus, though often, in order to display humility, newly appointed Emperors would often decline one or more of the honorifics given to Augustus. Just as often, as their reign progressed, Emperors would appropriate all of the titles, regardless of whether they had actually been granted by the Senate. The Civic Crown, consular insignia, and later the purple robes of a Triumphant general (toga picta) became the imperial insignia well into the Byzantine era, and were even adopted by many Germanic tribes invading the former Western empire as insignia of their right to rule.

Succession

Augustus' control of power throughout the Empire was so absolute that it allowed him to name his successor, a custom that had been abandoned and derided in Rome since the foundation of the Republic. At first, indications pointed toward his sister's son Marcellus, who had been married to Augustus' daughter Julia the Elder. However, Marcellus died of food poisoning in 23 BC. Reports of later historians that this poisoning, and other later deaths, were caused by Augustus' wife Livia Drusilla are inconclusive at best.After the death of Marcellus, Augustus married his daughter to his right hand man, Marcus Agrippa. This union produced five children, three sons and two daughters: Gaius Caesar, Lucius Caesar, Vipsania Julia, Agrippina the Elder, and Postumus Agrippa, so named because he was born after Marcus Agrippa died. Augustus' intent to make the first two children his heirs was apparent when he adopted them as his own children. Augustus also showed favor to his stepsons, Livia's children from her first marriage, Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus and Tiberius Claudius, after they had conquered a large portion of Germany.

After Agrippa died in 12 BC, Livia's son Tiberius divorced his own wife and married Agrippa's widow. Tiberius shared in Augustus' tribune powers, but shortly thereafter went into retirement. After the early deaths of both Lucius and Gaius in 2 and 4 respectively, and the earlier death of his brother Drusus (9 BC), Tiberius was recalled to Rome, where he was adopted by Augustus.

On August 19, 14, Augustus died. Postumus Agrippa and Tiberius had been named co-heirs. However, Postumus had been banished, and was put to death around the same time. Who ordered his death is unknown, but the way was clear for Tiberius to assume the same powers that his stepfather had.

His attributed last words were "Acta est fabula" ("the comedy is over"), from a text by Gaius Suetonius, "Vitae Caesarum, Divus Augustus" ("Life of Caesars, the Divine Augustus"), 97-99. The complete sentence would be "Acta est fabula, plaudite" ("The comedy is over, applaud!"), a common ending to ancient Roman comedies.

Augustus's legacy

The famous statue of Augustus at the Prima PortaAugustus was deified soon after his death, and both his borrowed surname, Caesar, and his title Augustus became the permanent titles of the rulers of Rome for the next 400 years, and were still in use at Constantinople fourteen centuries after his death. In many languages, caesar became the word for emperor, as in German (Kaiser) and in Russian (Tsar). The cult of the Divine Augustus continued until the state religion of the Empire was changed to Christianity in the 4th century. Consequently, there are many excellent statues and busts of the first, and in some ways the greatest, of the emperors. Augustus' mausoleum also originally contained bronze pillars inscribed with a record of his life, the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, which had also been disseminated throughout the empire during his lifetime.Many consider Augustus to be Rome's greatest emperor; his policies certainly extended the empire's life span and initiated the celebrated Pax Romana or Pax Augusta. He was handsome, intelligent, decisive, and a shrewd politician, but he was not perhaps as charismatic as Julius Caesar. Nevertheless, his legacy proved more enduring.

In looking back on the reign of Augustus and its legacy to the Roman world, its longevity should not be overlooked as a key factor in its success. As one ancient historian says, people were born and reached middle age without knowing any form of government other than the Principate. Had Augustus died earlier (in 23 BC, for instance), matters may have turned out differently.

The attrition of the civil wars on the old Republican oligarchy and the longevity of Augustus, therefore, must be seen as major contributing factors in the transformation of the Roman state into a de facto monarchy in these years. Augustus' own experience, his patience, his tact, and his political acumen also played their parts. He directed the future of the empire down many lasting paths, from the existence of a standing professional army stationed at or near the frontiers, to the dynastic principle so often employed in the imperial succession, to the embellishment of the capital at the emperor's expense.

Augustus' ultimate legacy was the peace and prosperity the empire enjoyed for the next two centuries under the system he initiated. His memory was enshrined in the political ethos of the Imperial age as a paradigm of the good emperor, and although every emperor adopted his name, Caesar Augustus, only a handful, such as Trajan, earned genuine comparison with him. His reign laid the foundations of a regime that lasted for 250 years.

The month of August (Latin Augustus) is named after Augustus; until his time it was called Sextilis (the sixth month of the Roman calendar). Commonly repeated lore has it that August has 31 days because Augustus wanted his month to match the length of Julius Caesar's July, but this is an invention of the 13th-century scholar Johannes de Sacrobosco. Sextilis in fact had 31 days before it was renamed, and it was not chosen for its length (see Julian calendar). A more widely held reason is that it was chosen since it was the month in which Cleopatra committed suicide.

Augustus boasted that he 'found Rome brick and left it marble'. Although this did not apply to the Subura slums, which were still as rickety and fire-prone as ever, he did leave a mark on the monumental topography of the centre and of the Campus Martius, with the Ara Pacis sundial (using an obelisk), the Temple of Caesar, the Forum of Augustus with its Temple of Mars Ultor, and also other projects either encouraged by him (eg Theatre of Balbus, Agrippa's construction of the Pantheon) or funded by him in the name of others, often relations (eg Portico of Octavia, Theatre of Marcellus). Even his own mausoleum was built before his death to house members of his family.

Have you ever heard of Caius Octavius? Most people have not, and wouldn’t recognize this great ruler by his birth name. Caius Octavius, adopted his great uncle’s heir name, Julius Caesar. After Julius Caesar’s death, Octavius formed an alliance with Marc Antony. Eventually Antony and Caesar parted their alliance because Antony had fallen in love with Cleopatra. A couple years later Octavius defeated Antony and Cleopatra and earned his name Augustus, which means divine. So Augustus Caesar was to known to the people as a great ruler.

Caius Octavius was born in 63 B.C. in Rome. He was adopted by Julius Caesar’s heir and given the name Caesar. When Julius Caesar was killed, he set out for the Roman Empire to get revenge on those who killed Julius. So he wanted to kill in spite of those who killed Julius. He made allies with enemies who would soon turn on him, but his short relations proved helpful to him. He learned of the betrayal of Antony with Cleopatra and in 31 B.C the senate made him General to fight against Antony. After he defeated Antony in battle, the senate honored him with the title Augustus in 27 B.C.

Leuven originated as a settlement of the Roman Empire along the trade route leading from Rome to what is now Trier, Germany. Caesar once covered 800 miles in ten days on one of the Roman roads, and a courier on horseback could cover 360 miles in two and a half days. Horse and mule carts averaged five to six miles per hour. Mail carts and wagons conveyed the post from town to town. This speed of transportation remained unequalled until the 19th century. Some of the roads, for instance, the Appian Way in Italy, are still in use today. Roman mail coaches were often covered so that the officials who traveled in them could sleep inside.

The Roman road system comprised some 50,000 miles of first class highways, stretching from Syria in the east to Britain in the west. Rome remained the center of the highway system, and each mile of road had a cylindrical stone milepost, which told the distance between that point and the Forum Romanum in the city of Rome. It took nearly 500 years to complete the Roman road system. The roads were built to exacting specifications: straight, graded, through tunnels, and over bridges. Roman chariots sped military personnel and important civil officials over the vast expanses of the Roman road system. While the trading of Agustus Caesar, Constantinople continued to trade with the coast of Gaul, the Iberian Peninsula, Africa, India and China.

Constantinople remained a prosperous city, populated by Romans, Greeks, Armenians, Syrians, Arabs, Asians and some Germans, all of them united by a common Roman citizenship and belief in Christ and the Trinity. Intermarriage among the different ethnicities was common, and by the 500s most people in Constantinople spoke Greek. A few spoke Latin, but Latin was declining and used chiefly on formal or official occasions. Prejudice was common only against those who could not speak Greek or who were not Catholic -- the essentials, according to some in Constantinople, for civilization. Germans made up the majority of those in Constantinople's army, and some soldiers were Huns. Many Germans labored on lands just outside the city, and some worked in Constantinople at menial jobs or as slaves in rich households.

Augustus Caesar’s beliefs were very liberal considered to most of the Roman emperors. He was determined to get money at all costs, by raising taxes. He was greedy and full of hatred. In Luke 12:15, Jesus warns not to be greedy because it will not bring you abundance. Caesar though in his greed made Rome a better place to live, he beautified it. He gave life to the ever dying city and is remember as the divine ruler.

born September 23, 63 BC

died August 19, AD 14, Nola, near Naples [Italy]

also called Augustus Caesar or (until 27 BC) Octavian , original name Gaius Octavius , adopted name Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus first Roman emperor, following the republic, which had been finally destroyed by the dictatorship of Julius Caesar, his great-uncle and adoptive father. His autocratic regime is known as the principate because he was the princeps, the first citizen, at the head of that array of outwardly revived republican institutions that alone made his autocracy palatable. With unlimited patience, skill, and efficiency, he overhauled every aspect of Roman life and brought durable peace and prosperity to the Greco-Roman world.Gaius Octavius was born on September 23, 63 BC, of a prosperous family that had long been settled at Velitrae (Velletri), southeast of Rome. His father, who died in 59 BC, had been the first of the family to become a Roman senator and was elected to the high annual office of the praetorship, which ranked second in the political hierarchy to the consulship. Gaius Octavius's mother, Atia, was the daughter of Julia, the sister of Julius Caesar; and it was Caesar who launched the young Octavius in Roman public life. At age 12 he made his debut by delivering the funeral speech for his grandmother Julia. Three or four years later he received the coveted membership of the board of priests (pontifices). In 46 BC he accompanied Caesar, now dictator, in his triumphal procession after his victory in Africa over his opponents in the Civil War; and in the following year, in spite of ill health, he joined the dictator in Spain. He was at Apollonia (now in Albania), completing his academic and military studies when, in 44 BC, he learned that Julius Caesar had been murdered.

Rise to power

Returning to Italy, he was told that Caesar in his will had adopted him as his son and had made him his chief personal heir. He was only 18 when, against the advice of his stepfather and others, he decided to take up this perilous inheritance and proceeded to Rome. Mark Antony (Marcus Antonius), Caesar's chief lieutenant, who had taken possession of his papers and assets and had expected that he himself would be the principal heir, refused to hand over any of Caesar's funds, forcing Octavius to pay the late dictator's bequests to the Roman populace from such resources as he could raise. Caesar's assassins, Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus, ignored him and withdrew to the east. Cicero, the famous orator who was one of Rome's principal elder statesmen, hoped to make use of him but underestimated his abilities.Celebrating public games, instituted by Caesar, to ingratiate himself with the city populace, Octavius succeeded in winning considerable numbers of the dictator's troops to his own allegiance. The Senate, encouraged by Cicero, broke with Antony, called upon Octavius for aid (granting him the rank of senator in spite of his youth), and joined the campaign of Mutina (Modena) against Antony, who was compelled to withdraw to Gaul. When the consuls who commanded the Senate's forces lost their lives, Octavius's soldiers compelled the Senate to confer a vacant consulship on him. Under the name of Gaius Julius Caesar he next secured official recognition as Caesar's adoptive son. Although it would have been normal to add “Octavianus” (with reference to his original family name), he preferred not to do so. Today, however, he is habitually described as Octavian (until the date when he assumed the designation Augustus).

Octavian soon reached an agreement with Antony and with another of Caesar's principal supporters, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who had succeeded him as chief priest. On November 27, 43 BC, the three men were formally given a five-year dictatorial appointment as triumvirs for the reconstitution of the state (the Second Triumvirate—the first having been the informal compact between Pompey, Crassus, and Julius Caesar). The east was occupied by Brutus and Cassius, but the triumvirs divided the west among themselves. They drew up a list of “proscribed” political enemies, and the consequent executions included 300 senators (one of whom was Antony's enemy Cicero) and 2,000 members of the class below the senators, the equites or knights. Julius Caesar's recognition as a god of the Roman state in January 42 BC enhanced Octavian's prestige as son of a god.

He and Antony crossed the Adriatic and, under Antony's leadership (Octavian being ill), won the two battles of Philippi against Brutus and Cassius, both of whom committed suicide. Antony, the senior partner, was allotted the east (and Gaul); and Octavian returned to Italy, where difficulties caused by the settlement of his veterans involved him in the Perusine War (decided in his favour at Perusia, the modern Perugia) against Antony's brother and wife. In order to appease another potential enemy, Sextus Pompeius (Pompey the Great's son), who had seized Sicily and the sea routes, Octavian married Sextus's relative Scribonia (though before long he divorced her for personal incompatibility).

These ties of kinship did not deter Sextus, after the Perusine War, from making overtures to Antony; but Antony rejected them and reached a fresh understanding with Octavian at the treaty of Brundisium, under the terms of which Octavian was to have the whole west (except for Africa, which Lepidus was allowed to keep) and Italy, which, though supposedly neutral ground, was in fact controlled by Octavian. The east was again to go to Antony, and it was arranged that Antony, who had spent the previous winter with Queen Cleopatra in Egypt, should marry Octavian's sister Octavia. The peoples of the empire were overjoyed by the treaty, which seemed to promise an end to so many years of civil war. In 38 BC Octavian formed a significant new link with the aristocracy by his marriage to Livia Drusilla.

But a reconciliation with Sextus Pompeius proved abortive, and Octavian was soon plunged into serious warfare against him. When his first operations against Sextus's Sicilian bases proved disastrous, he felt obliged to make a new compact with Antony at Tarentum (Taranto) in 37 BC. Antony was to provide Octavian with ships, in return for troops Antony needed for his forthcoming war against the empire's eastern neighbour Parthia and its Median allies. Antony handed over the ships, but Octavian never sent the troops. The treaty also provided for renewal of the Second Triumvirate for five years, until the end of 33 BC.

Rise to power

Returning to Italy, he was told that Caesar in his will had adopted him as his son and had made him his chief personal heir. He was only 18 when, against the advice of his stepfather and others, he decided to take up this perilous inheritance and proceeded to Rome. Mark Antony (Marcus Antonius), Caesar's chief lieutenant, who had taken possession of his papers and assets and had expected that he himself would be the principal heir, refused to hand over any of Caesar's funds, forcing Octavius to pay the late dictator's bequests to the Roman populace from such resources as he could raise. Caesar's assassins, Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus, ignored him and withdrew to the east. Cicero, the famous orator who was one of Rome's principal elder statesmen, hoped to make use of him but underestimated his abilities.Celebrating public games, instituted by Caesar, to ingratiate himself with the city populace, Octavius succeeded in winning considerable numbers of the dictator's troops to his own allegiance. The Senate, encouraged by Cicero, broke with Antony, called upon Octavius for aid (granting him the rank of senator in spite of his youth), and joined the campaign of Mutina (Modena) against Antony, who was compelled to withdraw to Gaul. When the consuls who commanded the Senate's forces lost their lives, Octavius's soldiers compelled the Senate to confer a vacant consulship on him. Under the name of Gaius Julius Caesar he next secured official recognition as Caesar's adoptive son. Although it would have been normal to add “Octavianus” (with reference to his original family name), he preferred not to do so. Today, however, he is habitually described as Octavian (until the date when he assumed the designation Augustus).

Octavian soon reached an agreement with Antony and with another of Caesar's principal supporters, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who had succeeded him as chief priest. On November 27, 43 BC, the three men were formally given a five-year dictatorial appointment as triumvirs for the reconstitution of the state (the Second Triumvirate—the first having been the informal compact between Pompey, Crassus, and Julius Caesar). The east was occupied by Brutus and Cassius, but the triumvirs divided the west among themselves. They drew up a list of “proscribed” political enemies, and the consequent executions included 300 senators (one of whom was Antony's enemy Cicero) and 2,000 members of the class below the senators, the equites or knights. Julius Caesar's recognition as a god of the Roman state in January 42 BC enhanced Octavian's prestige as son of a god.

He and Antony crossed the Adriatic and, under Antony's leadership (Octavian being ill), won the two battles of Philippi against Brutus and Cassius, both of whom committed suicide. Antony, the senior partner, was allotted the east (and Gaul); and Octavian returned to Italy, where difficulties caused by the settlement of his veterans involved him in the Perusine War (decided in his favour at Perusia, the modern Perugia) against Antony's brother and wife. In order to appease another potential enemy, Sextus Pompeius (Pompey the Great's son), who had seized Sicily and the sea routes, Octavian married Sextus's relative Scribonia (though before long he divorced her for personal incompatibility).

These ties of kinship did not deter Sextus, after the Perusine War, from making overtures to Antony; but Antony rejected them and reached a fresh understanding with Octavian at the treaty of Brundisium, under the terms of which Octavian was to have the whole west (except for Africa, which Lepidus was allowed to keep) and Italy, which, though supposedly neutral ground, was in fact controlled by Octavian. The east was again to go to Antony, and it was arranged that Antony, who had spent the previous winter with Queen Cleopatra in Egypt, should marry Octavian's sister Octavia. The peoples of the empire were overjoyed by the treaty, which seemed to promise an end to so many years of civil war. In 38 BC Octavian formed a significant new link with the aristocracy by his marriage to Livia Drusilla.

But a reconciliation with Sextus Pompeius proved abortive, and Octavian was soon plunged into serious warfare against him. When his first operations against Sextus's Sicilian bases proved disastrous, he felt obliged to make a new compact with Antony at Tarentum (Taranto) in 37 BC. Antony was to provide Octavian with ships, in return for troops Antony needed for his forthcoming war against the empire's eastern neighbour Parthia and its Median allies. Antony handed over the ships, but Octavian never sent the troops. The treaty also provided for renewal of the Second Triumvirate for five years, until the end of 33 BC.

Rise to power

Returning to Italy, he was told that Caesar in his will had adopted him as his son and had made him his chief personal heir. He was only 18 when, against the advice of his stepfather and others, he decided to take up this perilous inheritance and proceeded to Rome. Mark Antony (Marcus Antonius), Caesar's chief lieutenant, who had taken possession of his papers and assets and had expected that he himself would be the principal heir, refused to hand over any of Caesar's funds, forcing Octavius to pay the late dictator's bequests to the Roman populace from such resources as he could raise. Caesar's assassins, Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus, ignored him and withdrew to the east. Cicero, the famous orator who was one of Rome's principal elder statesmen, hoped to make use of him but underestimated his abilities.Celebrating public games, instituted by Caesar, to ingratiate himself with the city populace, Octavius succeeded in winning considerable numbers of the dictator's troops to his own allegiance. The Senate, encouraged by Cicero, broke with Antony, called upon Octavius for aid (granting him the rank of senator in spite of his youth), and joined the campaign of Mutina (Modena) against Antony, who was compelled to withdraw to Gaul. When the consuls who commanded the Senate's forces lost their lives, Octavius's soldiers compelled the Senate to confer a vacant consulship on him. Under the name of Gaius Julius Caesar he next secured official recognition as Caesar's adoptive son. Although it would have been normal to add “Octavianus” (with reference to his original family name), he preferred not to do so. Today, however, he is habitually described as Octavian (until the date when he assumed the designation Augustus).

Octavian soon reached an agreement with Antony and with another of Caesar's principal supporters, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who had succeeded him as chief priest. On November 27, 43 BC, the three men were formally given a five-year dictatorial appointment as triumvirs for the reconstitution of the state (the Second Triumvirate—the first having been the informal compact between Pompey, Crassus, and Julius Caesar). The east was occupied by Brutus and Cassius, but the triumvirs divided the west among themselves. They drew up a list of “proscribed” political enemies, and the consequent executions included 300 senators (one of whom was Antony's enemy Cicero) and 2,000 members of the class below the senators, the equites or knights. Julius Caesar's recognition as a god of the Roman state in January 42 BC enhanced Octavian's prestige as son of a god.

He and Antony crossed the Adriatic and, under Antony's leadership (Octavian being ill), won the two battles of Philippi against Brutus and Cassius, both of whom committed suicide. Antony, the senior partner, was allotted the east (and Gaul); and Octavian returned to Italy, where difficulties caused by the settlement of his veterans involved him in the Perusine War (decided in his favour at Perusia, the modern Perugia) against Antony's brother and wife. In order to appease another potential enemy, Sextus Pompeius (Pompey the Great's son), who had seized Sicily and the sea routes, Octavian married Sextus's relative Scribonia (though before long he divorced her for personal incompatibility). These ties of kinship did not deter Sextus, after the Perusine War, from making overtures to Antony; but Antony rejected them and reached a fresh understanding with Octavian at the treaty of Brundisium, under the terms of which Octavian was to have the whole west (except for Africa, which Lepidus was allowed to keep) and Italy, which, though supposedly neutral ground, was in fact controlled by Octavian. The east was again to go to Antony, and it was arranged that Antony, who had spent the previous winter with Queen Cleopatra in Egypt, should marry Octavian's sister Octavia. The peoples of the empire were overjoyed by the treaty, which seemed to promise an end to so many years of civil war. In 38 BC Octavian formed a significant new link with the aristocracy by his marriage to Livia Drusilla.

But a reconciliation with Sextus Pompeius proved abortive, and Octavian was soon plunged into serious warfare against him. When his first operations against Sextus's Sicilian bases proved disastrous, he felt obliged to make a new compact with Antony at Tarentum (Taranto) in 37 BC. Antony was to provide Octavian with ships, in return for troops Antony needed for his forthcoming war against the empire's eastern neighbour Parthia and its Median allies. Antony handed over the ships, but Octavian never sent the troops. The treaty also provided for renewal of the Second Triumvirate for five years, until the end of 33 BC.

Expansion of the empire

The death in 12 BC of Lepidus enabled Augustus finally to succeed him as the official head of the Roman religion, the chief priest (pontifex maximus). In the same year, Agrippa, too, died. Augustus compelled his widow, Julia, to marry Tiberius against both their wishes. During the next three years, however, Tiberius was away in the field, reducing Pannonia up to the middle Danube, while his brother Drusus crossed the Rhine frontier and invaded Germany as far as the Elbe, where he died in 9 BC. In the following year, Augustus lost another of his intimates, Maecenas, who had been the adviser of his early days and was an outstanding patron of letters.Tiberius, who replaced Drusus in Germany, was elevated in 6 BC to a share in his stepfather's tribunician power. But shortly afterward he went into retirement on the island of Rhodes. This was attributed to jealousy of his stepnephew Gaius Caesar, who was introduced to public life with a great fanfare in the following year; and the same compliments were paid to his brother Lucius in 2 BC, the year in which Augustus received his climactic title, “father of the country” (pater patriae). Gaius was sent to the east and Lucius to the west. Both, however, soon died. Tiberius returned home in 2, and in 4 Augustus adopted him as his son, who in turn was required to adopt Germanicus, the son of his brother Drusus. The powers conferred upon Tiberius made him almost Augustus's own equal in everything except prestige.

Tiberius's next task was to consolidate the invasion and provincial organization of Germany (AD 4–5). An invasion of Bohemia was planned and had already been launched from two directions when news came in 6 that Pannonia and Illyricum had revolted. It took three years for the rebellion to be put down; and this had only just been completed when Arminius raised the Germans against their Roman governor Varus and destroyed him and his three legions. As Augustus could not readily replace the troops, the annexation of western Germany and Bohemia was postponed indefinitely; Tiberius and Germanicus were sent to consolidate the Rhine frontier.

Although Augustus was now feeling his age, these years in association with Tiberius were marked by administrative innovations: the annexation of Judaea in AD 6 (its client king Herod the Great had died 10 years previously); the establishment at Rome (in the same year) of a fire brigade with police duties, supplemented seven years later by a regular police force (cohortes urbanae); the creation of a military treasury (aerarium militare) to defray soldiers' retirement bounties from taxes; and the conversion of the hitherto occasional appointment of prefect of the city (praefectus urbi) into a permanent office (AD 13). When, in the same year, the powers of Augustus were renewed for 10 years—such renewals had been granted at intervals throughout the reign—Tiberius was made his equal in every constitutional respect. In April, Augustus deposited his will at the House of the Vestals in Rome. It included a summary of the military and financial resources of the empire (breviarium totius imperii) and his political testament, known as the “Res Gestae Divi Augusti” (“Achievements of the Divine Augustus”). The best-preserved copy of the latter document is on the walls of the Temple of Rome and Augustus at Ankara, Turkey (the Monumentum Ancyranum). In AD 14 Tiberius was due to leave for Illyricum but was recalled by the news that Augustus was gravely ill. He died on August 19, and on September 17 the Senate enrolled him among the gods of the Roman state. By that time Tiberius had succeeded him as the second Roman emperor, though the formalities involved in the succession proved embarrassing both to himself and to the Senate because the “principate” of Augustus had not, constitutionally speaking, been heritable or continuous. Like other emperors, Tiberius assumed the designation “Augustus” as an additional title of his own. Agrippa Postumus, who had been named his co-heir but was later banished, was put to death. The order to kill him may already have been given by Augustus, but this is not certain.

Personality and achievement

Augustus was one of the great administrative geniuses of history. The gigantic work of reorganization that he carried out in every field of Roman life and throughout the entire empire not only transformed the decaying republic into a new, monarchic regime with many centuries of life ahead of it but also created a durable Roman peace, based on easy communications and flourishing trade. It was this Pax Romana that ensured the survival and eventual transmission of the classical heritage, Greek and Roman alike, and provided the means for the diffusion of Judaism and Christianity. Although his regime was an autocracy, Augustus, being a tactful and imaginative master of propaganda of many kinds, knew how to cloak that autocracy in traditionalist forms that would satisfy a war-worn generation—perhaps, most of all, the upper bourgeoisie immediately below the leading nobility, since it was they who benefited from the new order more than anyone. He was also able to win the approbation, through the patronage of Maecenas, of some of the greatest writers the world has ever known, including Virgil, Horace, and Livy.Their enthusiasm was partly due to Augustus's conviction that the Roman peace must be under Occidental, Italian control. This was in contrast to the views of Antony and Cleopatra, who had envisaged some sort of Greco-Roman partnership such as began to prevail only three or four centuries later. Augustus's narrower view, although modified by an informed admiration of Greek civilization, was based on his small-town Italian origins. These were also partly responsible for his patriotic, antiquarian attachment to the ancient religion and for his puritanical social policy.

Augustus was a cultured man, the author of a number of works (all lost): a pamphlet against Brutus, an exhortation to philosophy, an account of his own early life, a biography of Drusus, poems, and epigrams. The conventional view of his character distinguishes between his cruelty in early years and his mildness in later life. But there was not so much need for cruelty later on, and, when it was needed (notably in the suppression of alleged plots), he was still ready to apply it. It is probable that nothing short of this degree of political ruthlessness could have achieved such enormous results. His domestic life, however, was simple and homespun. Within his family, the successive deaths of those he had earmarked as his successors or helpers caused him much sadness and disappointment. His devotion to his wife Livia Drusilla remained constant, though, like other Romans, he was unfaithful. His surviving letters show kindliness to his relations. Yet he exiled his daughter Julia for offending against his public moral attitudes, and he exiled her daughter by Agrippa for the same reason; he also exiled the son of Agrippa and Julia, Agrippa Postumus, though the suspicion that he later had him killed is unproved. As for Augustus's male relatives who were his helpers, he was loyal to them but drove them as hard as he drove himself. He needed them because the burden was so heavy, and he especially needed them in the military sphere because he was not a great commander. In Agrippa and Tiberius and a number of others, he had men who supplied this deficiency, and although, on his deathbed, he is said to have advised against the further expansion of the empire, he himself, with their assistance, had expanded its frontiers in many directions.

His physical condition was subject to a host of ills and weaknesses, many of them recurrent. Indeed, in his early life, particularly, it was only his indomitable will that enabled him to survive—a strange preliminary to an unprecedented and unequaled life's work. His appearance is described by the biographer Suetonius:

He was unusually handsome and exceedingly graceful at all periods of his life, though he cared nothing for personal adornment. His expression, whether in conversation or when he was silent, was calm and mild.…He had clear, bright eyes, in which he liked to have it thought that there was a kind of divine power, and it greatly pleased him, whenever he looked keenly at anyone, if he let his face fall as if before the radiance of the sun. His teeth were wide apart, small and ill-kept; his hair was slightly curly and inclining to golden; his eyebrows met.…His complexion was between dark and fair. He was short of stature, but this was concealed by the fine proportion and symmetry of his figure, and was noticeable only by comparison with some taller person standing beside him.

Augustus's countenance proved a godsend to the Greeks and Hellenized easterners, who were the best sculptors of the time, for they elevated his features into a moving, never-to-be-forgotten imperial type, which Napoleon's artists, among others, keenly emulated. The contemporary portrait busts of Augustus, echoed on his coins, formed part of a significant renaissance of the arts in which Italic and Hellenic styles were discreetly and brilliantly blended. Still extant at Rome are the severe yet delicate reliefs of the Ara Pacis (“Altar of Peace”), depicting a religious procession in which the national leaders are taking part; there are also scenes from the Roman mythology. The altar was dedicated by the Senate and people of Rome in 13 BC to commemorate the pacification of Gaul and Spain.

The architectural masterpieces of the time were also numerous; and something of their monumental grandeur and classical purity can be seen today at Rome in the remains of the Theatre of Marcellus and of the massive Forum of Augustus, flanked by colonnades and culminating in the Temple of Mars the Avenger—the Avenger of Julius Caesar. Outside Rome, too, there are abundant memorials of the Augustan Age; on either side of the Alps, for example, there are monuments to celebrate the submission and loyalty of the local tribes, an elegant arch at Segusio (Susa), and a square stone trophy, topped by a cylindrical drum, at La Turbie. From Livia's mansion on the outskirts of Rome, at Prima Porta, comes a reminder that not all the art of the day was formal and grand. One of the rooms is adorned with wall paintings representing an enchanted garden; beyond a trellis are orchards and flower beds, in which birds and insects perch among the foliage. Augustus himself had no interest in personal luxury. Yet if ever he or his associates had any spare time, such were the rooms in which they spent it.