William Jennings Bryan

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Iimages and Physiognomic Interpretations

William Jennings Bryan—Statesman, Orator

(1860-1925) March 19, 1860, Salem, Illinois, 9:15 AM, LMT. (Source: Dewey quotes biography, Star of the Magi) 9:04 AM, LMT given in Sabian Symbols. Died, July 26, 1925.

(Ascendant, Gemini with Uranus in Gemini conjunct Ascendant from H12; MC Aquarius with Moon and NN also in Aquarius; Sun conjunct Neptune in Pisces; Mercury in Aries; Venus conjunct Pluto in Taurus; Mars in Sagittarius; Jupiter in Cancer; Saturn in Leo loosely conjunct IC;

American orator, lawyer and peerless leader of the Democratic party. Unsuccessful candidate for U.S. President three times--in 1896, 1900 and 1908. Member of the U.S. House of Representatives; newspaper editor. Watch “Cross of Gold” imagery.

R6 is clearly powerful as indicated by his oratory and conservative stances. His numerous idealistic schemes for the welfare of the country, however, failed to materialize.

Destiny is not a matter of chance, it is a matter of choice; it is not a thing to be waited for, it is a thing to be achieved.

(Mars in Sagittarius square Sun & Neptune.)Do not compute the totality of your poultry population until all the manifestations of incubation have been entirely completed.

I hope the two wings of the Democratic Party may flap together.

No one can earn a million dollars honestly.

(Venus conjunct Pluto in Taurus, square the Nodes.)The Imperial German Government will not expect the Government of the United States to omit any word or any act necessary to the performance of its sacred duty of maintaining the rights of the United States and its citizens and of safeguarding their free exercise and enjoyment.

Burn down your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again as if by magic; but destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country…. We will answer their demand for a gold standard by saying to them: You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.

If that vital spark that we find in a grain of wheat can pass unchanged through countless deaths and resurrections, will the spirit of man be unable to pass from this body to another?

In “The Prince of Peace,” a lecture delivered at Chautauquas and religious gatherings, starting in 1904, he phrased the idea this way: “If this invisible germ of life in the grain of wheat can thus pass unimpaired through three thousand resurrections, I shall not doubt that my soul has power to clothe itself with a body suited to its new existence when this earthly frame has crumbled into dust.”—Speeches of William Jennings Bryan, vol. 2, p. 284 (1909).

I can not wish you success in your effort to reject the treaty because while it may win the fight it may destroy our cause. My plan cannot fail if the people are with us and we ought not to succeed unless we do have the people with us.

The government being the people’s business, it necessarily follows that its operations should be at all times open to the public view. Publicity is therefore as essential to honest administration as freedom of speech is to representative government. “Equal rights to all and special privileges to none” is the maxim which should control in all departments of government.

Bryan prepared the ten rules as a synopsis of his speech so the newspapers might get the exact sense of it.

The chief duty of governments, in so far as they are coercive, is to restrain those who would interfere with the inalienable rights of the individual, among which are the right to life, the right to liberty, the right to the pursuit of happiness and the right to worship God according to the dictates of one’s conscience.

Anglo-Saxon civilization has taught the individual to protect his own rights; American civilization will teach him to respect the rights of others.

The humblest citizen of all the land, when clad in the armor of a righteous cause, is stronger than all the hosts of error.

“The way to develop self-confidence is to do the thing you fear and get a record of successful experiences behind you.”

“As long as there are human rights to be defended; as long as there are great interests to be guarded; as long as the welfare of nations is a matter for discussion, so long will public speaking have its place.”

(Uranus in Gemini conjunct Ascendant. Mercury in Aries trine Saturn in Leo.)“Never be afraid to stand with the minority when the minority is right, for the minority which is right will one day be the majority.”

“My place in history will depend on what I can do for the people and not on what the people can do for me.”

(Moon conjunct Chiron in Aquarius in 10th house. Sun, Neptune & Mercury in 11th house.)“There is no more reason to believe that man descended from some inferior animal than there is to believe that a stately mansion has descended from a small cottage.”

“The parents have a right to say that no teacher paid by their money shall rob their children of faith in God and send them back to their homes skeptical, or infidels, or agnostics, or atheists”

“If we have to give up either religion or education, we should give up education”

“All the ills from which America suffers can be traced to the teaching of evolution”

“Behold a republic standing erect while empires all around are bowed beneath the weight of their own armaments -- a republic whose flag is loved while other flags are only feared.”

“Evolution seems to close the heart to some of the plainest spiritual truths while it opens the mind to the wildest guesses advanced in the name of science.”

“If the Bible had said that Jonah swallowed the whale, I would believe it”

“In this fight I have the most intolerant and vindictive enemies I have ever met and I have the largest majority on my side I have ever had and I am discussing the greatest issue I have ever discussed.”

“None so little enjoy themselves, and are such burdens to themselves, as those who have nothing to do. Only the active have the true relish of life.” (Mars square Sun.)

“One miracle is just as easy to believe as another.”

“Eloquent speech is not from lip to ear, but rather from heart to heart.”

“Christian civilization is the greatest that the world has ever known because it rests on a conception of life that makes life one unending progress toward higher things, with no limit to advancement or development.”

“All the ills from which America suffers can be traced back to the teaching of evolution. It would be better to destroy every other book ever written, and save just the first three verses of Genesis.”

“The temptation was an absolute truth and the serpent was the tempter. For his insolence the snake was punished and condemned to crawl on its belly forever.”

“God may be a matter of indifference to the evolutionists, and a life beyond may have no charm for them, but the mass of mankind will continue to worship their creator and continue to find comfort in the promise of their Savior that he has gone to prepare a place for them.”

“There can be no settlement of a great cause without discussion, and people will not discuss a cause until their attention is drawn to it.”

(Uranus in Gemini conjunct Ascendant.)“Who are the people in the land of Nod? Where did Cain's wife come from? There are mysteries we should not question.”

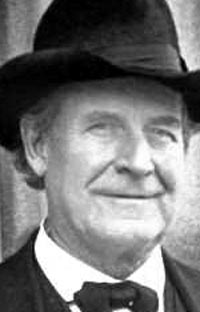

William Jennings Bryan, 1907William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, statesman, and politician. He was a three-time Democratic Party nominee for President of the United States noted for his deep, commanding voice. Bryan was a devout Presbyterian, a strong proponent of popular democracy, an outspoken critic of banks and railroads, a leader of the silverite movement in the 1890s, a dominant figure in the Democratic Party, a peace advocate, a prohibitionist, an opponent of Darwinism, and one of the most prominent leaders of the Progressive Movement. He was called "The Great Commoner" because of his total faith in the goodness and rightness of the common people.

He was one of the most energetic campaigners in American history, inventing the national stumping tour. In his presidential bids, he promoted Free Silver in 1896, anti-imperialism in 1900, and antitrust in 1908, calling on all Democrats to renounce conservatism, fight the trusts and big banks, and embrace progressive ideas. President Woodrow Wilson appointed him Secretary of State in 1913, but Bryan resigned in protest against Wilson's policies in 1915. In the 1920s he was a strong supporter of Prohibition, but is probably best known today for his negative criticism of Darwinism, which culminated in the Scopes Trial in 1925.

Background and early career

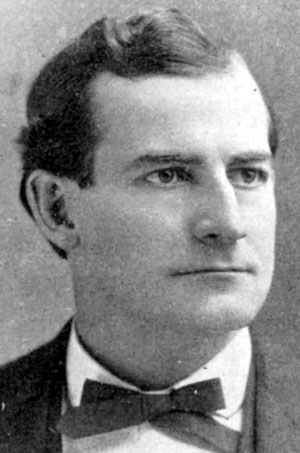

William Jennings Bryan as a young man.Bryan was born in Salem, in the Little Egypt region of southern Illinois, on March 19, 1860, the son of Silas and Mariah Bryan.Silas Bryan was born in 1822 in Virginia, of Irish stock. At age 18, he walked to Troy, Missouri to live with his elder brother. He attended McKendree College in Lebanon, Illinois, graduating with a Bachelor's degree in 1849, and eventually earning his master's. He then taught at Walnut Hill High School while preparing for the bar exam. During his brief tenure as a school teacher, he met Mariah Elizabeth Jennings: in 1852, now an attorney, he would marry his former pupil. The young couple settled in Salem, a young town with a population of approximately 2000. Shortly after this, Silas Bryan, a Jacksonian Democrat, won election to the Illinois State Senate, where he rubbed elbows with such luminaries as Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas. Silas lost his seat to a Republican in 1860, the year of William Jennings Bryan's birth, but quickly rebounded by winning election as a state circuit judge.

In 1866, the family moved to a 520-acre farm north of Salem, living in a ten-room house that was the envy of Marion County, complete with silver dining service and black servants. Silas served as a sort of "gentleman farmer" and William Jennings Bryan grew up in this agricultural setting. In 1872, Silas left the bench to run for the House of Representatives, with the backing of the Democratic and Greenback parties, but lost to a Republican. This was the last time he sought public office, and he would spend the rest of his life as a trial lawyer.

Both of Bryan's parents were devout Christians. Since his father was a Baptist and his mother was a Methodist, Bryan grew up attending Methodist services on Sunday mornings and Baptist services in the afternoon. In 1872, Mariah Bryan joined the Salem Baptists and the family now worshipped with the Baptists in the morning - at this point, William began spending his Sunday afternoons at the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. In 1874, at age 14, Bryan attended a revival held at the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, and, together with 70 of his classmates, was baptized and joined the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. In later life, Bryan would refer to the day of his baptism as the most important day in his life, but, being raised in a devout family, at the time it caused little change in his daily routine. As an adult, Bryan left the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in favor of the more mainstream Presbyterian Church in the USA.

Bryan was homeschooled until age 10, finding in the Bible and McGuffey Readers the truths he adhered to all his life, such as that gambling and liquor were evil and sinful. In 1874, shortly after his baptism, 14-year-old Bryan moved to Jacksonville to attend Whipple Academy, the academy attached to Illinois College. Following high school, he entered Illinois College and studied classics, graduating as valedictorian in 1881. During his time at Illinois College, Bryan was a proud member of the Sigma Pi Literary Society. He then moved to Chicago to study law at Union Law College.

He married Mary Baird in 1884; she became a lawyer and collaborated with him on all his speeches and writings. He practiced law in Jacksonville (1883–87), then moved to the boom city of Lincoln, Nebraska. He was elected to Congress in the Democratic landslide of 1890 and reelected by 140 votes in 1892. In 1894 he ran for the Senate but was overwhelmed in the Republican landslide.

First Battle: 1896

At the 1896 Democratic National Convention, Bryan galvanized the silver forces to defeat Bourbon Democrats tied to incumbent Democratic President Grover Cleveland. Thanks in large part to his Cross of Gold speech, Bryan won the nomination for President.His famous "Cross of Gold" speech, delivered prior to his nomination, lambasted Eastern monied classes for supporting the gold standard at the expense of the average worker. Bryan's stance, directly opposing the conservative Cleveland and the Bourbon Democrats, united the agrarian and silver factions and won the "Boy Orator of the Platte" the nomination. Bryan was said to have enjoyed this colorful nickname until opponents ridiculed it by saying that it was an appropriate thing to call Bryan, since the Platte River was narrow, shallow and widest at the mouth. Just 36, the youngest presidential nominee ever, Bryan managed to attract the support of most mainstream Democrats as well as disaffected Populists and Republican supporters of Free Silver in the West. Bryan formally received the nominations of Populist Party nomination and the Silver Republican Party in addition to the Democratic nomination. Thus voters from any party could vote for him without crossing party lines, an important advantage in an era of intense party loyalty. Republicans called Bryan a Populist. However, "Bryan's reform program was so similar to that of the Populists that he has often been mistaken for a Populist, but he remained a stanch Democrat throughout the Populist period."[1] The Populists nominated him in 1896 only--they refused to do so in previous and later elections.

Bryan as Populist swallowing the Democratic party; 1896 cartoon from the Republican magazine Judge.Bryan crusaded against the gold standard and the money interests, demanding Bimetallism and "free silver" at a ratio of 16:1. Most leading Democratic newspapers rejected his candidacy, so he took his cause directly to the people, making over 500 speeches in 27 states.

The Republicans nominated William McKinley on a program of prosperity through industrial growth, high tariffs, and sound money (that is, gold.) Republicans discovered that, by August, Bryan was solidly ahead in the South and West, and far behind in the Northeast. But he also appeared to be ahead in the Midwest, so the Republicans concentrated their efforts there. They counter-crusaded against Bryan, warning that he was a madman--a religious fanatic surrounded by anarchists--who would wreck the economy. By late September the Republicans felt they were ahead in the decisive Midwest, and began emphasizing that McKinley would bring prosperity to every group of Americans. McKinley scored solid gains among the middle classes, factory and railroad workers, prosperous farmers, and among the German Americans who rejected free silver. William McKinley won by a margin of 271 to 176 in the electoral college.

Conservatives in 1900 ridiculed Bryan's eclectic platform[edit]

War and Peace: 1898-1900

Although Bryan never won an election after 1892, he continued to dominate the Democratic party. He strongly supported going to war with Spain in 1898, and volunteered for combat, arguing that "Universal peace cannot come until justice is enthroned throughout the world. Until the right has triumphed in every land and love reigns in every heart, government must, as a last resort, appeal to force." Bryan volunteered and became a colonel of a Nebraska militia regiment; he spent the war in Florida and never saw combat.After the war, Bryan came to denounce the imperialism that resulted from it. He strongly opposed the annexation of the Philippines (though he did support the Treaty of Paris that ended the war). He ran as an anti-imperialist in 1900, finding himself in an awkward alliance with Andrew Carnegie and other millionaire anti-imperialists. Republicans mocked Bryan as indecisive, or even a coward, a theme echoed in the portrayal of the Cowardly Lion in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900). In 1900, he combined anti-imperialism with free silver, saying:

The nation is of age and it can do what it pleases; it can spurn the traditions of the past; it can repudiate the principles upon which the nation rests; it can employ force instead of reason; it can substitute might for right; it can conquer weaker people; it can exploit their lands, appropriate their property and kill their people; but it cannot repeal the moral law or escape the punishment decreed for the violation of human rights.[2]

His stamina was evident from his schedule. In a typical day he gave four hour-long speeches and shorter talks that added up to six hours of speaking. At an average rate of 175 words a minute, he turned out 63,000 words, enough to fill 52 columns of a newspaper. (No paper printed more than a column or two.) In Wisconsin, he made 12 speeches in 15 hours. [Coletta 1:272]. He held his base in the South, but lost part of the West as McKinley retained the Northeast and Midwest and rolled up a landslide.

1900-1912: on the Chautauqua circuit

Following his failed presidential bid in 1900, the 40-year-old Bryan re-examined his life and concluded that he had let his passion for politics obscure his calling as a Christian. He now prepared a number of speeches in defense of the Christian faith and hit the lecture circuit, especially the Chautauqua circuit. For the next 25+ years, Bryan would be the most popular Chautauqua speaker, delivering thousands of speeches, even while serving as secretary of state. He spoke on a wide variety of topics, but he preferred religious topics. His most popular lecture (and his personal favorite) was a lecture entitled "The Prince of Peace": in it, Bryan stressed that religion was the only solid foundation of morality, and that individual and group morality was the only foundation for peace and equality. Another famous lecture from this period, "The Value of an Ideal", was a stirring call to public service.As early as 1905, Bryan was warning Chautauquans of the dangers of Darwinism: "The Darwinian theory represents man reaching his present perfection by the operation of the law of hate - the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak. If this is the law of our development then, if there is any logic that can bind the human mind, we shall turn backward to the beast in proportion as we substitute the law of love. I choose to believe that love rather than hatred is the law of development."

Bryan also now threw himself into the work of the Social Gospel. Bryan served on organizations containing a large number of theological liberals: he sat on the temperance committee of the Federal Council of Churches and on the general committee of the short-lived Interchurch World Movement.

In the years following his 1900 presidential loss, Bryan founded a weekly magazine , The Commoner, calling on Democrats to dissolve the trusts, regulate the railroads more tightly and support the Progressive Movement. He regarded prohibition as a "local" issue and did not endorse it until 1910. In London in 1906, he presented a plan to the Inter-Parliamentary Peace Conference for arbitration of disputes that he hoped would avert warfare. He tentatively called for nationalization of the railroads, then backtracked and called only for more regulation. His party nominated gold bug Alton B. Parker in 1904, but Bryan was back in 1908, losing this time to William Howard Taft.

Secretary of State: 1913-1916

Cartoon depicting Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan reading news from the war fronts, 1914.After supporting Wilson in 1912, he was rewarded with the top job as Secretary of State. Wilson made all the major foreign policy decisions himself, only nominally consulting Bryan. Dedicated to peace (though not a pacifist), Bryan negotiated 28 treaties that promised arbitration of disputes before war broke out between that country and the United States; Germany never signed on. He supported American military intervention in the civil war in Mexico in 1914. Bryan resigned in June 1915 over Wilson's strong notes demanding "strict accountability for any infringement of [American] rights, intentional or incidental." He campaigned energetically for Wilson's reelection in 1916. When war finally was declared in April 1917, Bryan wrote Wilson, "Believing it to be the duty of the citizen to bear his part of the burden of war and his share of the peril, I hereby tender my services to the Government. Please enroll me as a private whenever I am needed and assign me to any work that I can do."[3] Wilson, however, did not allow Bryan to rejoin the military and did not offer him any wartime role, so he threw his energies into successful campaigns for Constitutional amendments on prohibition and women's suffrage.Prohibition Battles 1916-1925

Bryan moved to Florida in part to avoid the Nebraska ethnics (especially the German Americans) who were "wet" and opposed to prohibition. (Coletta 3:116). He remained as busy as ever, often filling lucrative speaking engagements. Always pious, during the final years of his life, he was extremely active in religious organizations and devoted himself to the defense of fundamentalist Christianity. (His father, a judge, was a Baptist, and his mother converted to this faith from Methodism when Bryan was 12. He and his sister later became Presbyterians.) After leaving the State Department, he shifted focus to social and moral issues, and to world disarmament. He refused to support the party nominee in 1920 because he was not dry enough. As one biographer explains,Bryan epitomized the prohibitionist viewpoint: Protestant and nativist, hostile to the corporation and the evils of urban civilization, devoted to personal regeneration and the social gospel, he sincerely believed that prohibition would contribute to the physical health and moral improvement of the individual, stimulate civic progress, and end the notorious abuses connected with the liquor traffic. Hence he became interested when its devotees in Nebraska viewed direct legislation as a means of obtaining antisaloon laws. (Coletta 2:8)

He was thus primarily interested in destroying the liquor interest, which controlled politics in many inner-city wards and seemed to be on the other side of every issue. His national campaigning helped Congress pass the 18th Amendment in 1918, which shut down all saloons starting in 1920. While prohibition was in effect, however, he did not work to secure better enforcement. He ignored the Ku Klux Klan, expecting it would soon fold. He strongly opposed wet Al Smith for the nomination in 1924; his brother Charles Bryan was put on the ticket as candidate for vice president to keep the Bryanites in line.

Fighting Darwinism: 1918-1924

In his famous Chautauqua lecture, "The Prince of Peace," Bryan had warned of the possibility that the theory of evolution could undermine the foundations of morality. However, at this point, he concluded "While I do not accept the Darwinian theory I shall not quarrel with you about it."This attitude changed when the horrors of the First World War convinced Bryan that Darwinism was not only a potential threat, but had in fact undermined morality. Before World War I, Bryan had been an optimist who believed that moral progress could achieve equality at home and, in the international field, peace between all the nations of the world. World War I convinced him that this optimism was misplaced and that moral progress seemed to have ground to a complete halt.

In concluding that Darwinism was responsible for the immorality of the present age, Bryan was heavily influenced by two books: the first was Headquarters Nights: A Record of Conversations and Experiences at the Headquarters of the German Army in Belgium and France by Vernon Kellogg (1917), which confirmed that most German military leaders were committed Darwinists who were sceptical of Christianity. The second was The Science of Power by Benjamin Kidd (1918), which argued that German nationalism, materialism, and militarism could be attributed to the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, which in turn was the logical outworking of the Darwinian hypothesis.

In 1920, Bryan told the World Brotherhood Congress that Darwinism was "the most paralyzing influence with which civilization has had to deal in the last century" and that Nietzsche, in carrying Darwinism to its logical conclusion, had "promulgated a philosophy that condemned democracy...denounced Christianity...denied the existence of God, overturned all concepts of morality...and endeavored to substitute the worship of the superhuman for the worship of Jehovah."

However, it was not until 1921 that Bryan saw the threat to morality posed by Darwinism as a major internal threat to the US. The major study which seemed to convince Bryan of this was James Henry Leuba's The Belief in God and Immortality, a Psychological, Anthropological and Statistical Study (1916). In this study, Leuba showed that a considerable number of college students lost their faith during the four years they spent in college. Bryan was horrified that the next generation of American leaders might have the degraded sense of morality which had prevailed in Germany and caused the Great War. Bryan decided it was time to act and launched his massive anti-evolution campaign.

The campaign kicked off when Union Theological Seminary in Virginia invited Bryan to deliver the James Sprunt Lectures in October 1921. The heart of the lectures was a lecture entitled "The Origin of Man", in which Bryan addressed what he saw as the question foundational to all other moral and political questions: what is the role of man in the universe and what is the purpose of man? For Bryan, religion was absolutely central to answering this question, and moral responsibility and the spirit of brotherhood could only rest on belief in God. The Darwinists, however, in calling into question religion, had laid the foundation for the bloodiest war in human history; had removed sympathy and brotherhood from the economic realm, replacing it with competition and survival of the fittest; and offered no program for improving life except for "scientific breeding" which would take hundreds of years to achieve.

The Sprunt lectures were published as In His Image, and sold over 100,000 copies, while "The Origin of Man was published separately as The Menace of Darwinism and also sold very well.

Bryan was worried that Darwinism was making grounds not only in the universities, but also within the church itself. (And it's worth pointing out that many universities and schools were still run by churches at this point.) The developments of 19th-century liberal theology, and higher criticism in particular, had left the door open to the point where many clergymen were willing to embrace Darwinism and claimed that it was not contradictory with their being Christians. Determined to put an end to this, Bryan, who had long served as a Presbyterian elder, decided to run for the position of Moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the USA. (Under presbyterian church governance, clergy and laymen are equally represented in the General Assembly, and the post of Moderator is open to any member of General Assembly.) Bryan's main competition in the race was the Rev. Charles F. Wishart, president of the College of Wooster, who had loudly endorsed the teaching of Darwinism in the college. Bryan lost to Wishart by a vote of 451-427.

However, Bryan continued his fight from the floor of the General Assembly. He convinced the Assembly to pass a resolution endorsing total abstinence from alcoholic beverages before turning his guns on Darwinism. He put forth a motion that no denominational funds should be spent at any university, college, or school where Darwinism was taught. However, the General Assembly opted instead for a milder motion, saying they disapproved of materialistic (as opposed to theistic) evolution, but refusing to cut off funds.

Bryan actively supported state laws banning public schools from teaching evolution; several southern states did pass such laws after Bryan addressed them. His participation in the highly publicized 1925 Scopes Trial served as a capstone to his career. Bryan was asked by William Bell Riley to represent as counsel the World Christian Fundamentals Association at the trial. During the trial Bryan took the stand and was questioned by defense lawyer Clarence Darrow about his views on the Bible. Biologist Stephen J. Gould has speculated that Bryan's antievolution views were a result of his Populist idealism and suggests that Bryan's fight was really against Social Darwinism. Others, such as biographer Michael Kazin, reject that conclusion based on Bryan's failure during the trial to attack the eugenics and white supremacy in the textbook, Civic Biology. [Kazin p 289] The national media reported the trial in great detail, with H. L. Mencken using Bryan as a foil for Southern ignorance and anti-intellectualism. Bryan died on July 26, 1925, only five days after the trial ended. School Superintendent Walter White proposed that Dayton should create a Christian college as a lasting memorial to Bryan; fund raising was successful and Bryan College opened in 1930.

Kazin (2006) considers him the first of the 20th-century "celebrity politicians" better known for their personalities and communications skills than their political views. Alan Wolfe has concluded that Bryan's "legacy remains complicated. Form and content mix uneasily in Bryan's politics. The content of his speeches . . . leads in a direct line to the progressive reforms adopted by 20th-century Democrats. But the form his actions took—-a romantic invocation of the American past, a populist insistence on the wisdom of ordinary folk, a faith-based insistence on sincerity and character—lead just as directly to the Republican Party of Karl Rove and George W. Bush."[4]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

BRYAN, William Jennings, (father of Ruth Bryan Owen), a Representative from Nebraska; born in Salem, Marion County, Ill., March 19, 1860; attended the public schools and Whipple Academy, Jacksonville, Ill.; was graduated from Illinois College, Jacksonville, Ill., in 1881; studied law at Union College in Chicago; was graduated in 1883 and commenced practice at Jacksonville, Ill., in 1883; moved to Lincoln, Nebr., in 1887 and continued the practice of law; elected as a Democrat to the Fifty-second and Fifty-third Congresses (March 4, 1891-March 3, 1895); declined to be a candidate for reelection in 1894; unsuccessful candidate for election to the United States Senate in 1894; delegate to the Democratic National Conventions in 1896, 1904, 1912, 1920, and 1924; unsuccessful Democratic candidate for President in 1896, 1900, and 1908; was endorsed by the Populist and Silver Republican Parties in the first and second campaigns; during the Spanish-American War raised the Third Regiment, Nebraska Volunteer Infantry, in May 1898 and was commissioned colonel; established a newspaper, “The Commoner,” at Lincoln, Nebr., in 1901; engaged in editorial writing and delivering Chautauqua lectures; Secretary of State in the Cabinet of President Wilson and served from March 4, 1913, until June 9, 1915, when he resigned; resumed his former pursuits of lecturing and writing; established his home in Miami, Fla., in 1921; died while attending court in Dayton, Tenn., July 26, 1925; interment in Arlington National Cemetery.