Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2005

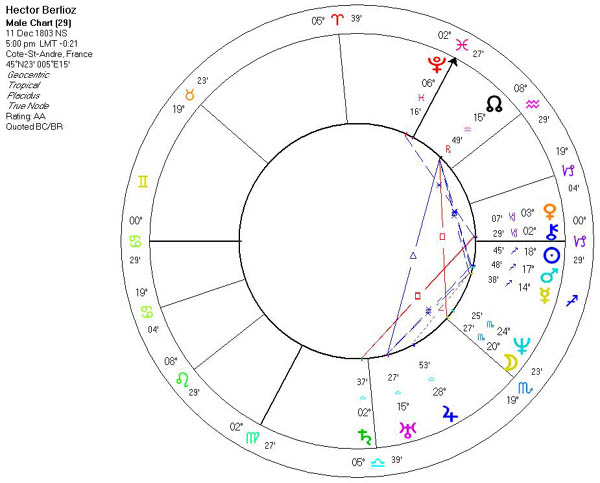

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

At least I have the modesty to admit that lack of modesty is one of my failings.

Every composer knows the anguish and despair occasioned by forgetting ideas which one had no time to write down.

(Sun, Mercury & Mars in Sagittarius.)Love cannot express the idea of music, while music may give an idea of love.

The luck of having talent is not enough; one must also have a talent for luck.

(Jupiter in Libra in 5th house.)Time is a great teacher, but unfortunately it kills all its pupils.

To render my works properly requires a combination of extreme precision and irresistible verve, a regulated vehemence, a dreamy tenderness, and an almost morbid melancholy. Hector Berlioz

"In my opinion, the trombone is the true head of the family of wind instruments, which I have named the 'epic' one. It possesses nobility and grandeur to the highest degree; it has all the serious and powerful tones of sublime musical poetry, from religious, calm and imposing accents to savage, orgiastic outburst. Directed by the will of the master, the trombones can chant like a choir of priests, threaten, utter gloomy sighs, a mournful lament, or a bright hymn of glory; they can break forth into awe-inspiring cries and awaken the dead or doom the living with their fearful voices."

Hector Berlioz on Creative Dreaming

Two years ago, at a time when my wife's state of health was involving me in a lot of expense, but there was still some hope of its improving, I dreamed one night that I was composing a symphony, and heard it in my dream. On waking the next morning I could recall nearly the whole of the first movement, which was an allegro in A minor in two-four time (that is all I now remember about it).I was going to my desk to begin writing it down, when I suddenly thought: "If I do, I shall be led on to compose the rest. My ideas always tend to expand nowadays, this symphony could well be on an enormous scale. I shall spend perhaps three or four months on the work (I took seven to write 'Romeo and Juliet'), during which time I shall do no articles, or very few, and my income will diminish accordingly. When the symphony is written I shall be weak enough to let myself be persuaded by my copyist to have it copied, which will immediately put me a thousand or twelve hundred francs in debt. Once the parts exist, I shall be plagued by the temptation to have the work performed. I shall give a concert, the receipts of which will barely cover one half of the costs--that is inevitable these days. I shall lose what I haven't got, and be short of money to provide for the poor invalid, and no longer able to meet my personal expenses or pay my son's allowance on the ship he will shortly be joining."

These thoughts made me shudder, and I threw down my pen, thinking: "What of it? I shall have forgotten it by tomorrow!" That night the symphony again appeared and obstinately rang in my head. I heard the allegro in A minor quite distinctly. More, I seemed to see it written. I woke in a state of feverish excitement. I hummed the theme to myself; its form and character pleased me exceedingly. I was on the point of getting up. Then my previous thoughts recurred and held me fast. I lay still, steeling myself against temptation, clinging to the hope that I would forget. At last I fell asleep; and when I next awoke, all recollection of it had vanished forever.

“I believe nothing.”

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869): "The essentially barbaric timbre of this instrument [the serpent] would have been far more appropriate to the ceremonies of the bloody cult of the Druids than to those of the Catholic religion. There is only one exception to be made - the case where the Serpent is employed in the Masses for the Dead, to reinforce the terrible plainsong of the Dies Irae. Then, no doubt, its cold and abominable howling is in place."

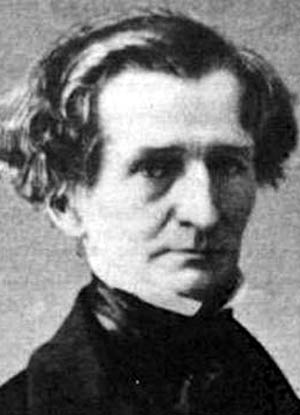

Portrait of Berlioz by Signol, 1832Louis Hector Berlioz (December 11, 1803 – March 8, 1869) was a French Romantic composer best known for the Symphonie fantastique, first performed in 1830, and for his Grande Messe des morts Requiem of 1837, with its tremendous resources that include four antiphonal brass choirs.

Berlioz, by Alphonse LegrosBerlioz was born in France at La Côte-Saint-André in the département of Isère, between Lyon and Grenoble. His father was a physician, and young Hector was sent to Paris to study medicine at the age of eighteen. Berlioz was horrified by the process of dissection, and, despite his father's disapproval, he abandoned his career path in medicine to study music a year later. He then attended the Paris Conservatoire studying opera and composition.

He became identified early on with the French romantic movement. Among his friends were writers such as Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, and Honoré de Balzac. Later, Théophile Gautier wrote, "Hector Berlioz seems to me to form with Hugo and Delacroix, the Trinity of Romantic Art."

Berlioz is said to have been innately romantic, experiencing emotions deeply from early childhood. This manifested itself in his weeping at passages of Virgil as a child, and later in a series of love affairs. At the age of 23, his unrequited (at first) love for the Irish Shakespearean actress Harriet Constance Smithson was the inspiration for his Symphonie fantastique. In 1830, the same year as the symphony's premiere, Berlioz won the Prix de Rome.

Berlioz's letters were considered so overly passionate by Smithson that she initially refused his advances. The symphony which these emotions are said to inspire was received as startling and vivid. The autobiographic nature of this piece of program music was also considered sensational at the time. After his return to Paris from his two years study in Rome, he finally married Smithson when she had finally attended a performance of the Symphonie Fantastique. She quickly realized that it was his depiction of his passionate letters to her. However, after only a few years, the relationship quickly fell apart. (Kamien 242)

During his lifetime, Berlioz was more famous as a conductor than a composer. He regularly toured Germany and England where he conducted operas and symphonic music, both his own and music composed by others. He met virtuoso violinist and composer Niccolò Paganini a few times and, according to Berlioz's memoirs, Paganini offered him 20,000 francs after he saw Harold in Italy performed live as the money was intended as a reward for writing a viola piece for the violin virtuoso to perform as his own.

Hector Berlioz is buried in the Cimetiere de Montmartre with his two wives, Harriet Smithson (died 1854) and Marie Recio (died 1862).

The music of Berlioz enjoyed a revival during the 1960s and 1970s, due in large part to the efforts of British conductor Colin Davis, who recorded his entire oeuvre, bringing a number of Berlioz's lesser-known works to the light. Davis's recording of Les Troyens was the first complete recording of that work. The work, which Berlioz never saw staged in its entirety during his life, is now revived regularly.

In 2003, the bicentenary of Berlioz's birth, a proposal was made to remove his remains to the Panthéon, but it was blocked by President Jacques Chirac in a political dispute over Berlioz's worthiness as a symbol of the glory of France in comparison to such figures as Andre Malraux, Jean Jaures, and Alexandre Dumas. In his land of birth, Berlioz still remains something of the neglected prophet.

Berlioz had a keen affection for literature, and many of his best compositions are inspired by literary works. For Symphonie Fantastique, Berlioz was inspired by Thomas de Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. For La damnation de Faust, Berlioz drew on Goethe's Faust; for Harold in Italy, he drew on Byron's Childe Harold; for Benvenuto Cellini, he drew on Cellini's own autobiography. For Roméo et Juliette, Berlioz turned, of course, to Shakespeare's Romeo And Juliet. For his magnum opus, the monumental opera Les Troyens, Berlioz turned to Virgil's epic poem The Aeneid. For his last opera, the comic opera Béatrice et Bénédict, Berlioz prepared a libretto based loosely on Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing.

Apart from the many literary influences, Berlioz also championed Beethoven who was at the time unknown in France. The performance of the "Eroica" symphony in Paris seems to have been a turning point for Berlioz's compositions. Next to Beethoven, Berlioz worshipped Christoph Willibald Gluck, Etienne Mehul, Carl Maria von Weber, and Gaspare Spontini.

In addition to the Symphonie Fantastique, some other works of Berlioz currently in the standard orchestral repertoire include his "légende dramatique" La damnation de Faust and "symphonie dramatique" Roméo et Juliette (symphony) (both large-scale works for mixed voices and orchestra), the song cycle Les nuits d'été (originally for voice and piano, later with an orchestral accompaniment), and his symphonic viola concerto Harold in Italy.

The unconventional music of Berlioz irritated the established concert and opera scene. Berlioz had to arrange for his own performances as well as pay for them himself. This took a heavy toll on him financially and emotionally. He had about 1,200 loyal attendants to his performances who guaranteed ticket sales, but the nature of his large works—involving hundreds of performers—made financial success difficult. His journalistic abilities became essential for him to make a living and he survived as a witty critic emphasizing the importance of drama and expressivity in musical entertainment.

While Berlioz is best known as a composer, he was also a prolific writer, and supported himself for many years writing musical criticism. He wrote in a bold, vigorous style, at times imperious and sarcastic. Evenings With the Orchestra (1852) is a scathing satire of provincial musical life in 19th century France. Berlioz's Memoirs (1870) paints a magisterial portrait of the Romantic era through the eyes of one of its chief protagonists.

A pedagogic work, The Treatise on Modern Instrumentation and Orchestration, established his reputation as a master of orchestration. The work was closely studied by Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss and served as the foundation for a subsequent textbook by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov who as a music student attended the concerts Berlioz conducted in Moscow and St Petersburg. Music critic Norman Lebrecht wrote:

Before the visits of Berlioz, there was no Russian music. His was the paradigm that inspired the genre. Tchaikovsky raided the Symphonie fantastique like a tuck-shop for his third symphony. Mussorgsky died with a copy of the Berlioz Treatise on his bed. [1]

On 7 February Louis Berlioz, a young doctor from La Côte Saint André in the Département of Isère, and Marie-Antoinette-Josephine, daughter of Nicolas Marmion, a lawyer from Meylan, are married in her home town on. She is 18 years old, he is 27.

Louis-Hector Berlioz is born at 5.00pm on 11 December at No. 83 rue nationale, La Côte Saint-André and is baptised in the chapel of the Church of Saint André (14 December). His paternal grand-father Nicolas Marmion and great-grand-mother Sophie Brochier are, respectively, his god-father and god-mother.

Dr and Madame Berlioz will have five other children of whom two will reach adulthood, Nanci and Adèle.

ca 1811 Following the closure of the local seminary, Dr Louis Berlioz takes charge of his son’s education.

ca 1815 Berlioz receives his first communion in spring where he undergoes his first musical experience.

Berlioz learns to read Virgil in the original Latin and translate it into French under his father’s tuition.

1816 Berlioz learns to play the flageolet; earliest attempts at composition.

1818 Composition of two quintets for flute and strings. A theme from one of them is reused later in the overture to Les Francs-Juges.

1819 In January Dr Berlioz buys a flute and later a guitar for his son who begins lessons on the instrument with his new teacher Dorant.

1821 Berlioz is made bachelier ès lettres at Grenoble on 22 March.

He departs for Paris to read medicine in late October.

First visit to the Opéra, where he sees a performance of Gluck’s masterpiece Iphigénie en Tauride (November). Shortly after he writes to his sister Nanci about this first experience.

1822 He decides to devote himself to music. He is introduced by a friend to Lesueur, director of the Royal Chapel and professor at the Paris Conservatoire, who gives him encouragement.

1823 Berlioz writes his very first article at the age of 20, in the form of a letter to the journal Le Corsaire, which is published in the issue of 12 August 1823

During a visit to La Côte in spring and early summer his family fails to make him abandon his interest in music, he wins over his father but his mother curses him.

Composition of Estelle et Némorin (now lost); the libretto is by Hyacinthe-Christophe Gerono, after Florian’s poem of the same title.

During the winter he writes an oratorio entitled Le Passage de la mer Rouge (The Crossing of the Red Sea; now lost) and shows it to Lesueur, who admits him as one of his private pupils.

1824 He is made Bachelier ès sciences physiques (12 January).

He finally abandons medicine and embarks on a career in music.

In December he attends a performance of Der Freischütz at the Odéon Theatre; this is Berlioz’s first acquaintance with the music of Weber.

1825

His Messe solennelle is successfully performed at Saint-Roch on 10 July. The autograph score, believed to have been destroyed by him in 1827, is miraculously discovered in 1992 in a chest in the Church of St Carolus Borromeus in Antwerp.

Berlioz starts working on an opera, Les Francs-Juges, on a libretto by his friend Humbert Ferrand.

During the winter he composes La Révolution grecque (La Scène héroïque).

1826 He is eliminated from the preliminary round of the Prix de Rome competition, his fugue submitted for consideration is unsuccessful (early July).

He enrols at the Conservatoire in classes of Lesueur and Reicha (October).

He completes Les Francs-Juges in October. The libretto is later rejected by the Opéra (May 1828).1830 Composition of the Symphonie fantastique (January-April).

He starts a relationship with Camille Moke, a young talented pianist. This is, it seems, his first relationship with a woman. They are subsequently engaged.

Berlioz meets Liszt, who has attended the concert; it is the beginning of a long friendship between the two men which continues until the late 1850s. Later Liszt, who will champion Berlioz for years to come, transcribes the Symphonie fantastique for piano.

1831 He meets Mendelssohn in Rome for the first time; they will meet again some years later when Berlioz goes on his first concert tour in Germany (1843).

He writes an autobiographical sketch, the first he is known to have written, which forms the basis of an article on him by his friend Joseph d’Ortigue, published on 23 December in the Revue de Paris.

1833 After a prolonged and (for Berlioz) painful courtship, Hector and Harriet marry on 3 October at the British Embassy in Paris; Liszt is one of the witnesses; Berlioz’s friend Thomas Gounet pays for the expenses. Berlioz and his bride spend a short honeymoon in Vincennes near Paris. The marriage takes place against the vehement opposition of Berlioz’s family, except for his younger sister, Adèle.

1834 Hector and Harriet’s son Louis is born on 14 August. Berlioz’s younger sister Adèle is the little boy’s godmother.

1838 Berlioz’s mother dies on 18 February.

1841 Berlioz starts his relationship with the singer Marie Recio.

1844 Berlioz and his wife Harriet separate; he moves in with Marie Recio in her flat at 41 rue de Provence; Harriet continues to live at 43 and then 65 rue Blanche. From now on Berlioz will maintain two households; he continues to provide for Harriet and, a few years later when she becomes seriously ill, he pays for all her medical expenses as well.

1850 Berlioz’s sister Nanci dies of breast cancer on 4 May.

1851 Death of Spontini (24 January).

1854 Harriet Smithson dies on 3 March and is buried the next day in the Cimetière Saint-Vincent, a small cemetery in Montmartre. Later in 1864 she will be moved to Montmartre Cemetery, to her final resting place which she will share with Berlioz and his second wife Marie Recio.

1856 In July and August he visits Plombières (to take waters on his doctor’s advice) and Baden-Baden for the annual concerts.

Berlioz and Marie move to 4 rue de Calais in October; this will be Berlioz’s last domicile in Paris till his death.

Onset of an intestinal illness from which he will suffer for the rest of his life and which will progressively get worse.

1860 Berlioz’s younger sister Adèle dies of heart-related illness on 2 March, shortly after being visited by Berlioz. She is buried in Vienne where she has been living with her husband and two daughters.

1862 Completion of Béatrice et Bénédict, loosely based on Shakespeare’s Much ado about nothing; both libretto and score are by Berlioz himself. The autograph score is dated 25 February 1862.

Death of Halévy (17 March); Berlioz fails in his application to succeed him as permanent secretary of the Académie des beaux-arts.

Berlioz’s second wife, Marie Recio, dies of a heart attack on 13 June at the age of 48, while staying with some friends at Saint-Germain near Paris. She is buried at Montmartre Cemetery on 16 June and later moved to a private plot donated by one of Berlioz’s friends Édouard Alexandre.

Berlioz meets a young woman called Amélie at Montmartre Cemetery; though she is only 24 he comes close to her (late June).

First performances of Béatrice et Bénédict at Baden-Baden on 9 and 11 August. Madame Charton-Demeur sings the role of Béatrice.

Berlioz gives to Vladimir Stasov the manuscript of his Te Deum which he donates to the municipal library of St-Petersburg (11 September)

Publication of À Travers Chants (September).

1863 Berlioz ends his relationship with Amélie at her request and is deeply upset (mid-February)

Les Troyens is dropped by the Opéra but accepted by Carvalho, director of the newly re-built Théâtre-Lyrique (mid February).

Visit to Weimar in April to conduct Béatrice et Bénédict (8 and 10 April); while in Germany he also goes to Loewenberg to give a concert there (19 April).

He conducts L’Enfance du Christ in Strasbourg on 22 June.

Visit to Baden-Baden in August to revive Béatrice et Bénédict in an augmented form (14 and 18 August).

Berlioz publishes his last signed article for the Journal des débats on 8 October, on Bizet’s opera Les Pêcheurs de perles [The Pearl Fishers].

He encounters great difficulties in staging Les Troyens in a truncated form at the Théâtre-Lyrique. It is eventually premièred on 4 November and runs to 21 performances until 20 December. Madame Charton-Demeur sings the role of Didon. Paris will wait another 140 years to see Les Troyens staged complete and without cuts in 2003 at the Théâtre du Châtelet, on the opposite side of the Place du Châtelet.

7. 1864-1869: Final years

1864

Arrangement of the Marche troyenne as a concert piece (January).

Harriet Smithson’s remains are moved to the cemetery in Montmartre from the Saint Vincent Cemetery which was due for demolition (3 February or 3 March).

Berlioz finally resigns as music critic of the Journal des débats (end March).

Death of Meyerbeer (2 May).

Berlioz adds the Postface to the Memoirs (first half of July)

Berlioz is made Officier de la Légion d’honneur at the same time as his friend Legouvé (12 August).

On 22 August, Berlioz hears from a friend that Amélie, who was suffering from poor health, had died at the age of 26. A week later, while walking in the Montmartre Cemetery, Berlioz discovers Amélie’s grave; she had been dead for six months. He is devastated.

Berlioz travels to Dauphiné to visit relatives: Adèle’s family in Vienne (30 August), Camille Pal (Nanci’s husband) in Grenoble (ca. 18 September). He revisits Meylan (22 September) and the next day meets Estelle Fornier in Lyon for the first time in over 40 years. He begins a regular correspondence with her.

1865

The final section of the Memoirs, the Trip to Dauphiné, is completed and dated on 1 January. Berlioz sends the completed text to the publishers.

Completion of the printing of the Memoirs (1200 copies, on 29 July). Berlioz sends a copy to Estelle Fornier; the remaining copies are stored in his office at the Conservatoire awaiting posthumous publication (a copy of this early print is now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, and another in the Hector Berlioz Museum in La Côte).

Visit to Estelle Fornier in Geneva (18-25 August), followed by visits to his brothers-in-law Camille Pal in Grenoble (ca. 25-29 August) and Marc Suat in Vienne (29 August-9 September).

1866

Berlioz meets Liszt for the last time (21 April).

Last meeting with his son Louis (early August).

Visit to Estelle Fornier in Geneva (15-19 September).

Successful revival of Gluck’s Alceste at the Opéra (first performance on 12 October). During the preceding months Berlioz had supervised the rehearsals (from July onwards).

Death of Joseph d’Ortigue, one of Berlioz’s closest friends (20 November).

1867

Visit to Cologne to give a concert (26 February).

His son Louis, who was commander of a merchant ship, dies of yellow fever in Havana on 5 June; Berlioz only receives the news on 29 June and is devastated.

In his study at the Conservatoire Berlioz destroys a large number of papers and memorabilia associated with his career (mid July).

Berlioz draws up his will (29 July).

He visits Adèle’s family in Vienne in August and Estelle Fornier in St Symphorien, where she now lives with her son and his family, in September. The visit on 9 September is the last time that he sees her.

He accepts an invitation from Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna to make a concert tour in Russia (18 September).

Departure from Paris for Russia (12 November).

1868

Berlioz returns to Paris from Russia exhausted (17 February).

Last trip to Nice early in March, where Berlioz suffers two falls. He adds a codicil to his will.

In August he visits Grenoble for the last time to address a choral festival.

1869 8 March: Berlioz dies at his Paris home No. 4 rue de Calais at 30 minutes past midday. His faithful servant, his mother-in-law Madame Martin and his devoted friends Ernest Reyer and Madame Charton-Demeur are with him in his final hours. The funeral service is held at the Église de la Trinité (11 March). He joins his two wives at Montmartre Cemetery.