Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2006

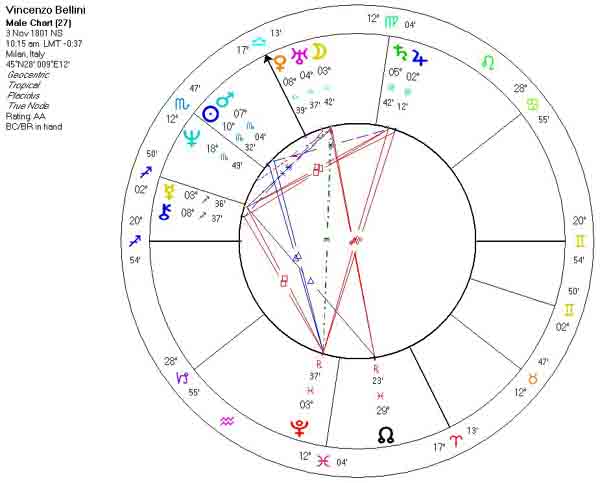

Astro-Rayological Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

Two lines only, o my dear friend, to give you word about my health, which is at the breaking point from the great fatigue that I am experiencing because of having to compose the opera in a short time, and whose fault is that? that of my usual and original poet, the God of Sloth!.

Vincenzo Salvatore Carmelo Francesco Bellini (November 3, 1801 – September 23, 1835) was an Italian opera composer. Known for his flowing melodic line, Bellini was the quintessential composer of Bel canto opera.

Born in Catania, Sicily, Italy, Bellini was a child prodigy from a highly musical family and legend has it he could sing an air of Valentino Fioravanti at eighteen months, began studying music theory at two, the piano at three, and by the age of five could play well. His first composition dates from his sixth year. Regardless of the veracity of these claims, it is certain that Bellini grew up in a musical household and that a career as a musician was never in doubt.

Having learned from his grandfather, Bellini left provincial Catania in June 1819 to study at the conservatory in Naples, with a stipend from the municipal government of Catania. By 1822 he was in the class of the director Nicolò Zingarelli, studying the masters of the Neapolitan school and the orchestral works of Haydn and Mozart. It was the custom at the Conservatory to introduce a promising student to the public with a dramatic work: the result was Bellini's first opera Adelson e Salvini an opera semiseria that was presented at the Conservatory's theater. Bianca e Gernando met with some success at the Teatro San Carlo, leading to an offer from the impresario Barbaia for an opera at La Scala. Il pirata was a resounding immediate success and began Bellini's faithful and fruitful collaboration with the librettist and poet Felice Romani, and cemented his friendship with his favored tenor Giovanni Battista Rubini, who had sung in Bianca e Gernando.

Bellini spent the next years, 1827–33 in Milan, where all doors were open to him. Supported solely by his opera commissions, for La straniera (1828) was even more successful than Il pirata, sparking controversy in the press for its new style and its restless harmonic shifts into remote keys, he showed the taste for social life and the dandyism that Heinrich Heine emphasized in his literary portrait of Bellini (Florentinische Nächte, 1837). Opening a new theater in Parma, his Zaira (1829) was a failure at the Teatro Ducale, but Venice welcomed I Capuleti e i Montecchi, which was based on the same Italian sources as Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet.

The next five years were triumphant, cut short by Bellini's premature death.

Bellini died in Puteaux, near Paris of acute inflammation of the intestine, and was buried in the cemetery of Père Lachaise, Paris; his remains were removed to the cathedral of Catania in 1876. The Museo Belliniano, Catania, preserves memorabilia and scores.

Bellini is best known for his opera Norma, the title role of which is considered the most difficult role in the soprano repertoire. During the 20th century, only a small number of singers were able to assay it with success: Rosa Ponselle in the early 1920s, and later Joan Sutherland in the 1950s and 1960s. Maria Callas was the famous Norma of the postwar period; she performed it many times and recorded it in the studio twice.

The youngest of the three, Vincenzo Bellini completes the triumvirate of composers that define Bel Canto. His special contribution to the art form was to be revered by the masters of late Romantic opera – Giuseppe Verdi and Richard Wagner – and his influence would linger into the 20th century. In contrast to his more famous contemporaries, Gioachino Rossini and Gaetano Donizetti, Bellini was from the deep south, born on the island of Sicily. He was the eldest of seven children in a musical family. Little is known about his general education, but he must have exhibited enough natural talent to be granted a scholarship from the city of Catania to study music in Naples.

At the Naples Conservatory Bellini had the usual battery of teachers, the most significant being Niccolò Zingarelli, himself an established composer, and Girolamo Crescentini, a vocal teacher counting among his students Isabella Colbran (who would become one of the city's leading singers and eventually Rossini's first wife). Bellini's graduation work, Adelson e Salvini, was successful enough to generate a commission from the royal court. Bianca e Fernando was deemed a moderate success, given that applause was forbidden in Naples during a command performance unless it was initiated by the reigning monarch. These first two works relied on soon-to-be outdated formulas but were pleasing enough to attract the attention of impresario Domenico Barbaja. In addition to controlling the royal theaters (and the gambling syndicate) in Naples, Barbaja had his hands in the management at La Scala. There he secured Bellini a commission for his third opera, Il pirata, which was to become a triumph for the young composer, whose star was now ascending.

Il pirata was the beginning of a fruitful partnership between Bellini and librettist Felice Romani – they would collaborate on all of the composer's remaining operas except his last. Romani's greatest gift was his attention to the diction of the text. In Bellini's hands the words received even greater subtlety, a stylistic feature often lost on audiences not familiar with the Italian language. Their next opera was an even greater achievement, and with La straniera the composer threw off the shackles of Rossinian imitation (an irresistible tendency in the wake of the master's popularity) and moved toward a more personal style. His teacher Zingarelli vehemently opposed Rossini's practice of employing richer orchestration and superfluous ornamentation and encouraged his protégé to focus on melody, which would be enriched by Bellini's recollection of folk songs of his native Sicily. The result became the composer's trademark style – long, serpentine, stepwise vocal lines meandering over simple accompaniment. Such an approach worked perfectly in tandem with the singer's careful elocution of Romani's meticulously chosen words.

Because Bellini believed he invested more into his craft, thus being only able to produce about one opera a year (unlike other composers of the day who could produce up to three or four), he demanded higher fees for his commissions, topping those received by Rossini only a few years before. At least one theater acquiesced, Parma's new Teatro Ducale, but only after Rossini turned it down. For the theater's inaugural opera Bellini and Romani turned to Voltaire's Zaire, a subject matter very much in vogue at the time, with an exotic setting, a soprano heroine, a pants-role contralto, a weighty bass and a tenor in a subsidiary role. Stylistically he backpeddled a bit, incorporating some of Rossini's bravura vocal techniques. Still, Zaira was not well received, and Bellini salvaged much of the score in his next opera, I Capuleti e i Montecchi.

After Capuleti's success, Bellini considered setting Victor Hugo's Hernani but recanted after work had begun. The play had created a scandal at its premiere only a few months earlier, and the composer feared the libretto would draw rebuke from the censors (Verdi would boldly set this same story 14 years later as Ernani). Instead he was drawn to a ballet, La sonnambule, ou L'arrivée d'un nouveau seigneur, later made into a vaudeville by the veteran French playwright/librettists Eugène Scribe and Casimir Delavigne. Sleepwalking was of special interest to Romantic-period writers and audiences, and the new opera was an instant hit. Bellini followed La sonnambula with Norma, a recent French play whose heroine displayed Medea and Semiramide tendencies. It was greeted coolly on its first night but was soon to become a hallmark of the bel canto style.

During the composition of their next project, a rift developed between Bellini and his librettist. Romani had over-committed himself (he had been working for four other composers at the time), leaving their latest opus stalled in its tracks. Bellini had to appeal to the Venetian government, which forced Romani to honor his contract, but the composer was still rushed to complete Beatrice di Tenda, which opened beyond its original date. The opera was based on another ballet, in this instance adapted from a historical event: the accusation of adultery and beheading of Beatrice, whose husband belonged to the powerful but cruel Visconti family of Milan.

Now at the top of his game, Bellini went first to London, then settled in Paris, intent on pursuing an international career. Capuleti and Pirata both made their premieres at the Théâtre Italien, but Bellini hoped for a commission from the Opéra, the more distinguished house. None was forthcoming, in part due to his insistence on both the usual high fee and a prime or an additional lump-sum payable to the composer upon signing an agreement. Also the requirement of a French text was troubling to some extent since Bellini was not familiar with the language, and the words normally played such a large role in his compositions. In spite of this barrier, Bellini still was able to make important Parisian contacts with the leading artistic figures of the Romantic period, including Frédéric Chopin, Franz Liszt, Alfred de Mussy, Heinrich Heine, Victor Hugo, George Sand, Alexandre Dumas père and Horace Vernet, among others.

In 1834 Bellini received a fresh offer from the Théâtre Italien for a new work. This would become I puritani, styled after a play in the vein of Sir Walter Scott's British scenarios; still it was clogged with so much intrigue and politics that large sections had to be excised. Bellini refused to work with Romani again (though they did mend the fence soon after) and instead turned to Count Carlo Pepoli, a versifier of some merit with little stage-writing experience. The new work was a triumph, outshining Donizetti's new opera for Paris, Marino Faliero, which opened shortly after. This delighted Bellini to no end, as he was constantly jealous of his rival composers (he once remarked that two men involved in the same metier could never be friends).

I puritani was Bellini's final work. While spending the summer in the Parisian suburb of Puteaux, the 33-year-old composer's chronic amoebic infection flared up and became life-threatening. A certain degree of mystery surrounds his final days, which were spent alone after his landlords had fled, no doubt fearing that his symptoms indicated an outbreak of cholera. Rossini was quick to take care of the funeral arrangements, and Bellini was buried in the Père Lachaise cemetery, mourned by his fellow composers Cherubini, Carafa and Paer, who with Rossini served as pallbearers. Bellini died exactly as Heinrich Heine had once predicted – like Mozart and Raphael, all young and at the height of their genius.