Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2006

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Iimages and Physiognomic Interpretations

A thing is not necessarily true because badly uttered, nor false because spoken magnificently.

Beauty is indeed a good gift of God; but that the good may not think it a great good, God dispenses it even to the wicked.

By faithfulness we are collected and wound up into unity within ourselves, whereas we had been scattered abroad in multiplicity.

Charity is no substitute for justice withheld.

Complete abstinence is easier than perfect moderation.

Faith is to believe what you do not see; the reward of this faith is to see what you believe.

Find out how much God has given you and from it take what you need; the remainder is needed by others.

Forgiveness is the remission of sins. For it is by this that what has been lost, and was found, is saved from being lost again.

Give me chastity and continence, but not yet.

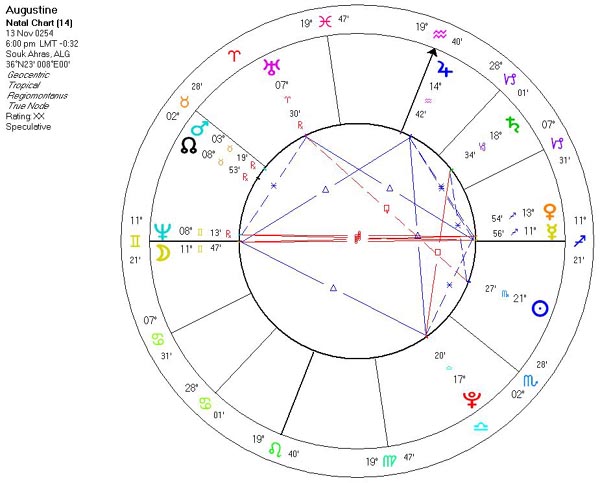

Jupiter on MCGod had one son on earth without sin, but never one without suffering.

God judged it better to bring good out of evil than to suffer no evil to exist.

Humility is the foundation of all the other virtues hence, in the soul in which this virtue does not exist there cannot be any other virtue except in mere appearance.

I have learnt to love you late, Beauty at once so ancient and so new!

I want my friend to miss me as long as I miss him.

If two friends ask you to judge a dispute, don't accept, because you will lose one friend; on the other hand, if two strangers come with the same request, accept because you will gain one friend.

Love, and do what you like.

Miracles are not contrary to nature, but only contrary to what we know about nature.

No eulogy is due to him who simply does his duty and nothing more.

Passion is the evil in adultery. If a man has no opportunity of living with another man's wife, but if it is obvious for some reason that he would like to do so, and would do so if he could, he is no less guilty than if he was caught in the act.

Patience is the companion of wisdom.

Pray as though everything depended on God. Work as though everything depended on you.

Seek not to understand that you may believe, but believe that you may understand.

(Neptune conjunct Ascendant; Venus & Mercury conjunct Descendant.)The greatest evil is physical pain.

The people who remained victorious were less like conquerors than conquered.

The purpose of all wars, is peace.

The words printed here are concepts. You must go through the experiences.

The World is a book, and those who do not travel read only a page.

Mercury in Sagittarius conjunct DescendantThere is no possible source of evil except good.

To seek the highest good is to live well.

If we did not have rational souls, we would not be able to believe.

Understanding is the wages of faith. Do not believe yourself healthy. Immortality is health; this life is a long sickness.

We make a ladder for ourselves out of our vices when we trample them.

To touch God a little with our mind is a great blessing, to grasp him is impossible.

The intellectual knowledge of eternal things pertains to wisdom; the rational knowledge of temporal things, to science.

It is not the punishment but the cause that makes the martyr.

Carnal lust rules where there is no love of God.

What am I then, my God? What is my nature? A life varied, multifaceted and truly immense.

Thy word remaineth for ever, which word now appeareth unto us in the riddle of the clouds, and through the mirror of the heavens, not as it is: because that even we, though the well beloved of thy Son, yet it hath not yet appeared what we shall be. He looked through the lattice of our flesh and he spake us fair, yea, he set us on fire, and we hasten on his scent. But when he shall appear, then shall we be like him, for we shall see him as he is: as he is, Lord, will our sight be, though the time be not yet.

If bodies please thee, praise God on occasion of them, and turn back thy love upon their Maker; lest in these things which please thee, thou displease. If souls please thee, be they loved in God: for they too are mutable, but in Him they are firmly established.

The good Christian should beware of mathematicians, and all those who make empty prophecies. The danger already exists that the mathematicians have made a covenant with the devil to darken the spirit and to confine man in the bonds of Hell.

Source: DeGenesi ad Litteram, Book II, xviii, 37 [Note: mathematician = astrologer][Though he avoided outright endorsement of the view, fifth-century Church Father Saint Augustine was clearly familiar with the theory of the spherical earth:]

"They [those who believe that "there are men on the other side of the earth"] fail to observe that even if the world is held to be global or rounded in shape, or if some process of reasoning should prove this to be the case, it would still not necessarily follow that the land on the opposite side is not covered by masses of water."Anger is a weed; hate is the tree.

Free curiosity is of more value than harsh discipline.

Of this I am certain, that no one has ever died who was not destined to die some time. Now the end of life puts the longest life on a par with the shortest. . . . And of what consequence is it what kind of death puts an end to life, since he who has died once is not forced to go through the same ordeal a second time? They, then, who are destined to die, need not be careful to inquire what death they are to die, but into what place death will usher them.

(Pluto in Libra square Saturn in Capricorn.)Six is a number perfect in itself, and not because God created the world in six days; rather the contrary is true. God created the world in six days because this number is perfect, and it would remain perfect, even if the work of the six days did not exist.

To be under pressure is inescapable. Pressure takes place through all the world; war, siege, the worries of state. We all know men who grumble under these pressures and complain. They are cowards. They lack splendour. But there is another sort of man who is under the same pressure but does not complain, for it is the friction which polishes him. It is the pressure which refines and makes him noble

If you would attain to what you are not yet, you must always be displeased by what you are. For where you are pleased with yourself there you have remained. Keep adding, keep walking, keep advancing.

Imagine the vanity of thinking that your enemy can do you more damage than your enmity.

When all is said and done, is there any more wonderful sight, any moment when man's reason is nearer to some sort of contact with the nature of the world than the sowing of seeds, the planting of cuttings, the transplanting of shrubs or the grafting of slips.

You aspire to great things? Begin with little ones.

If the thing believed is incredible, it is also incredible that the incredible should have been so believed.

We enjoy some gratification when our good friends die; for though their death leaves us in sorrow, we have the consolatory assurance that they are beyond the ills by which in this life even the best of men are broken down or corrupted.

Of the first and bodily death, we may say that to the good it is good, and evil to the evil. But, doubtless, the second, because it happens to none of the good, can be good for none.

The death . . . of the soul takes place when God forsakes it, as the death of the body when the soul forsakes it.

Understanding is the reward of faith. Therefore seek not to understand that thou mayest believe, but believe that thou mayest understand.

God is more truly imagined than expressed, and He exists more truely than imagined.

I was in love with loving.

Will is to grace as the horse is to the rider.

The function of perfection - to make one know one's imperfection.

The superfluities of the rich are the necessaries of the poor. They who possess superfluities, possess the goods of others.

All sin is a kind of lying.

But those wars also are just, without doubt, which are ordained by God Himself, in Whom is no iniquity, and Who knows everyman's merits.

You (God) have not only commanded continence, that is, from what things we are to restrain our love, but also justice, that is, on what we are to bestow our love.

There is something in humility which strangely exalts the heart.

Women should not be enlightened or educated in any way. They should, in fact, be segregated as they are the cause of hideous and involuntary erections in holy men.

He who created us without our help will not save us without our consent.

He that is jealous is not in love.

Renouncement: the heroism of mediocrity.

Despise not yourselves, ye women; the Son of God was born of a woman

While the best men are guided by love, most mean are still goaded by fear

Hell was made for the inquisitive.

Augustine of Hippo

Bishop and Doctor of the Church

Born November 13, 354, Souk-Ahras, Algeria

Died August 28, 430, Hippo

Feast August 28

Attributes child; dove; pen; shell, pierced heart

Patronage brewers; Bridgeport, Connecticut; Cagayan de Oro, Philippines; Ida, Philippines; Kalamazoo Michigan; printers; Saint Augustine, Florida; sore eyes; Superior, Wisconsin; theologians; Tucson, ArizonaAurelius Augustinus, Augustine of Hippo, or Saint Augustine (November 13, 354–August 28, 430) was one of the most important figures in the development of Western Christianity. In Roman Catholicism, he is a saint and pre-eminent Doctor of the Church. Many Protestants, especially Calvinists, consider him to be one of the theological fountainheads of Reformation teaching on salvation and grace. Born in Africa as the eldest son of Saint Monica, he was educated and baptized in Italy. His works—including The Confessions, which is often called the first Western autobiography—are still read by Christians around the world.

Saint Augustine was born in 354 in Tagaste, a provincial Roman city in North Africa. He was raised and educated in Carthage. His mother Monica was a devout Catholic[1] and his father Patricius a pagan, but Augustine followed the controversial Manichaean religion, much to the horror of his mother. As a youth Augustine lived a hedonistic lifestyle for a time, and in Carthage, he developed a relationship with a young woman who would be his concubine for over a decade, with whom he had a son. His education and early career was in philosophy and rhetoric, the art of persuasion and public speaking. He taught in Tagaste and Carthage, but desired to travel to Rome where he believed the best and brightest rhetoricians practiced. However, Augustine grew disappointed with the Roman schools, which he found apathetic. Once the time came for his students to pay their fees they simply fled. Manichean friends introduced him to the prefect of the City of Rome, Symmachus, who had been asked to provide a professor of rhetoric for the imperial court at Milan.

"St Augustine and Monica" (1846), by Ary Scheffer.The young provincial won the job and headed north to take up his position in late 384. At age thirty, Augustine had won the most visible academic chair in the Latin world, at a time when such posts gave ready access to political careers. However, he felt the tensions of life at an imperial court, lamenting one day as he rode in his carriage to deliver a grand speech before the emperor, that a drunken beggar he passed on the street had a less careworn existence than he.

His mother Monica pressured him to become a Catholic, but it was the bishop of Milan, Ambrose, who had most influence over Augustine. Ambrose was a master of rhetoric like Augustine himself, but older and more experienced. Prompted in part by Ambrose's sermons, and other studies, including a disappointing meeting with a key exponent of Manichaean theology, Augustine moved away from Manichaeism; but instead of becoming Catholic like Ambrose and Monica, he converted to a pagan Neoplatonic approach to truth, saying that for a time he had a sense of making real progress in his quest, although he eventually lapsed into skepticism.

Augustine's mother had followed him to Milan and he allowed her to arrange a society marriage, for which he abandoned his concubine (however he had to wait two years until his fiancée came of age; he promptly took up in the meantime with another woman). It was during this period Augustine of Hippo uttered his famous prayer, "Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet" [da mihi castitatem et continentiam, sed noli modo] (Conf., VIII. vii (17)).

In the summer of 386, after having read an account of the life of Saint Anthony of the Desert which greatly inspired him, Augustine underwent a profound personal crisis and decided to convert to Christianity, abandon his career in rhetoric, quit his teaching position in Milan, give up any ideas of marriage (much to the horror of his mother), and devote himself entirely to serving God and the practices of priesthood, which included celibacy. Key to this conversion was the voice of a small girl he heard at one point telling him in a sing-song voice to 'Take up and read' the Bible, at which point he opened the Bible at random and fell upon a passage from St. Paul. He would detail his spiritual journey in his famous Confessions, which went on to become a classic of both Christian theology and world literature. Ambrose baptized Augustine, along with his son, on Easter day in 387, and soon thereafter in 388 he returned to Africa. On his way back to Africa his mother died, as did his son soon after, leaving him relatively alone in the world without family.

Upon his return to north Africa he created a monastic foundation at Tagaste for himself and a group of friends. In 391 he was ordained a priest in Hippo Regius, (now Annaba, in Algeria). He became a famous preacher (more than 350 preserved sermons are believed to be authentic), and was noted for combating the Manichaean heresy, to which he had formerly adhered.

In 396 he was made coadjutor bishop of Hippo (assistant with the right of succession on the death of the current bishop), and remained as bishop in Hippo until his death in 430. He left his monastery, but continued to lead a monastic life in the episcopal residence. He left a Rule (Latin, Regula) for his monastery that has led him to be designated the "patron saint of Regular Clergy," that is, parish clergy who live by a monastic rule.

Augustine died on August 28, 430, during the siege of Hippo by the Vandals. He is said to have encouraged its citizens to resist the attacks, primarily on the grounds that the Vandals adhered to the Arian heresy.

Influence as a theologian and thinker

Detail of St. Augustine in a stained glass window by Louis Comfort Tiffany in the Lightner Museum, St. Augustine, Florida.Augustine remains a central figure, both within Christianity and in the history of Western thought. In both his philosophical and theological reasoning, he was greatly influenced by Stoicism, Platonism and Neoplatonism, particularly by the work of Plotinus, author of the Enneads, probably through the mediation of Porphyry and Victorinus (as Pierre Hadot has argued). His generally favorable outlook upon Neoplatonic thought contributed to the "baptism" of Greek thought and its entrance into the Christian and subsequently the European intellectual tradition. His early and influential writing on the human will, a central topic in ethics, would become a focus for later philosophers such as Schopenhauer and Nietzsche.It is largely due to Augustine's arguments against the Pelagians, who did not believe in original sin, that Western Christianity has maintained the doctrine of original sin. However, Eastern Orthodox theologians, while they believe all humans were damaged by the original sin of Adam and Eve, have key disputes with Augustine about this doctrine, and as such this is viewed as a key source of division between East and West.

Augustine's writings helped formulate the theory of the just war. He also advocated the use of force against the Donatists, asking "Why ... should not the Church use force in compelling her lost sons to return, if the lost sons compelled others to their destruction?" (The Correction of the Donatists, 22–24)

St. Thomas Aquinas took much from Augustine's theology while creating his own unique synthesis of Greek and Christian thought after the widespread rediscovery of the work of Aristotle.

While Augustine's doctrine of divine predestination would never be wholly forgotten within the Catholic Church, finding eloquent expression in the works of Bernard of Clairvaux, Reformation theologians such as Martin Luther and John Calvin would look back to him as the inspiration for their avowed capturing of the Biblical Gospel. Later, within the Catholic Church, the writings of Cornelius Jansen, who claimed heavy influence from Augustine, would form the basis of the movement known as Jansenism; some Jansenists went into schism and formed their own church.

Augustine was canonized by popular recognition and recognized as a Doctor of the Church in 1303 by Pope Boniface VIII. His feast day is August 28, the day on which he is thought to have died. He is considered the patron saint of brewers, printers, theologians, sore eyes, and a number of cities and dioceses.

The latter part of Augustine's Confessions consists of an extended meditation on the nature of time. Catholic theologians generally subscribe to Augustine's belief that God exists outside of time in the "eternal present"; that time only exists within the created universe.

Augustine's meditations on the nature of time are closely linked to his consideration of the human ability of memory. Frances Yates in her 1966 study, The Art of Memory argues that a brief passage of the Confessions, X.8.12, in which Augustine writes of walking up a flight of stairs and entering the vast fields of memory (see text and commentary)clearly indicates that the ancient Romans were aware of how to use explicit spatial and architectural metaphors as a mnemonic technique for organizing large amounts of information. A few French philosophers have argued that this technique can be seen as the conceptual ancestor of the user interface paradigm of virtual reality.[citation needed]

According to Leo Ruickbie, Augustine's arguments against magic, differentiating it from miracle, were crucial in the early Church's fight against paganism and became a central thesis in the later denunciation of witches and witchcraft.

Natural knowledge and biblical interpretation

A more clear distinction between "metaphorical" and "literal" in literary texts arose with the rise of the Scientific Revolution, although its source could be found in earlier writings, such as those of Herodotus (5th century BC). It was even considered heretical to interpret the Bible literally at times (cf. Origen, St. Jerome). Augustine took the view that the Biblical text should not be interpreted literally if it contradicts what we know from science and our God-given reason. In an important passage on his "The Literal Interpretation of Genesis" (early 5th century, AD), St. Augustine wrote:"It not infrequently happens that something about the earth, about the sky, about other elements of this world, about the motion and rotation or even the magnitude and distances of the stars, about definite eclipses of the sun and moon, about the passage of years and seasons, about the nature of animals, of fruits, of stones, and of other such things, may be known with the greatest certainty by reasoning or by experience, even by one who is not a Christian. It is too disgraceful and ruinous, though, and greatly to be avoided, that he [the non-Christian] should hear a Christian speaking so idiotically on these matters, and as if in accord with Christian writings, that he might say that he could scarcely keep from laughing when he saw how totally in error they are. In view of this and in keeping it in mind constantly while dealing with the book of Genesis, I have, insofar as I was able, explained in detail and set forth for consideration the meanings of obscure passages, taking care not to affirm rashly some one meaning to the prejudice of another and perhaps better explanation." (The Literal Interpretation of Genesis 1:19–20, Chapt. 19 [AD 408])

"With the scriptures it is a matter of treating about the faith. For that reason, as I have noted repeatedly, if anyone, not understanding the mode of divine eloquence, should find something about these matters [about the physical universe] in our books, or hear of the same from those books, of such a kind that it seems to be at variance with the perceptions of his own rational faculties, let him believe that these other things are in no way necessary to the admonitions or accounts or predictions of the scriptures. In short, it must be said that our authors knew the truth about the nature of the skies, but it was not the intention of the Spirit of God, who spoke through them, to teach men anything that would not be of use to them for their salvation." (ibid, 2:9)Creation

In "The Literal Interpretation of Genesis" Augustine took the view that everything in the universe was created simultaneously by God, and not in seven days like a plain account of Genesis would require. He argues that the six-day structure of creation presented in the book of Genesis represents a logical framework, rather than the passage of time in a physical way. Augustine also doesn’t envisage original sin as originating structural changes in the universe, and even suggests that the bodies of Adam and Eve were already created mortal before the Fall. Apart from his specific views, Augustine recognizes that the interpretation of the creation story is difficult, and remarks that we should be willing to change our mind about it as new information comes up. [1]In "The City of God", Augustine also defended what would be called today as Young Earth creationism. In the specific passage, Augustine rejected both the immortality of the human race proposed by pagans, and contemporary ideas of ages (such as those of certain Greeks and Egyptians) that differed from the Church's sacred writings:

"Let us, then, omit the conjectures of men who know not what they say, when they speak of the nature and origin of the human race. For some hold the same opinion regarding men that they hold regarding the world itself, that they have always been... They are deceived, too, by those highly mendacious documents which profess to give the history of many thousand years, though, reckoning by the sacred writings, we find that not 6000 years have yet passed." (Augustine, Of the Falseness of the History Which Allots Many Thousand Years to the World’s Past, The City of God, Book 12: Chapt. 10 [AD 419]).

Augustine and the Jews

Augustine wrote in Book 18, Chapter 46 of The City of God [2] (one of his most celebrated works along with The Confessions): "The Jews who slew Him, and would not believe in Him, because it behooved Him to die and rise again, were yet more miserably wasted by the Romans, and utterly rooted out from their kingdom, where aliens had already ruled over them, and were dispersed through the lands (so that indeed there is no place where they are not), and are thus by their own Scriptures a testimony to us that we have not forged the prophecies about Christ."Augustine deemed this scattering important because he believed that it was a fulfillment of certain prophecies, thus proving that Jesus was the Messiah. This is because Augustine believed that the Jews who were dispersed were the enemies of the Christian Church. He also quotes part of the same prophecy that says "Slay them not, lest they should at last forget Thy law". Some people have used Augustine's words to attack Jews as anti-Christian, while others have used them to attack Christians as anti-Jewish. See Christianity and anti-Semitism.

Augustine was born at Tagaste on 13 November, 354. Tagaste, now Souk-Ahras, about 60 miles from Bona (ancient Hippo-Regius), was at that time a small free city of proconsular Numidia which had recently been converted from Donatism. Although eminently respectable, his family was not rich, and his father, Patricius, one of the curiales of the city, was still a pagan. However, the admirable virtues that made Monica the ideal of Christian mothers at length brought her husband the grace of baptism and of a holy death, about the year 371.

Augustine received a Christian education. Once when very ill he asked for baptism, but all danger being soon passed he deferred receiving the sacrament, thus yielding to a deplorable custom of the times. His association with "men of prayer" left three great ideas deeply engraven upon his soul: a Divine Providence, the future life with terrible sanctions, and, above all, Christ the Saviour. "From my tenderest infancy, I had in a manner sucked with my mother's milk that name of my Saviour, Thy Son; I kept it in the recesses of my heart; and all that presented itself to me without that Divine Name, though it might be elegant, well written, and even replete with truth, did not altogether carry me away"

In 373, an entirely new inclination manifested itself in his life, brought about by the reading Cicero's "Hortensius" whence he imbibed a love of the wisdom which Cicero so eloquently praises. Thenceforward Augustine looked upon rhetoric merely as a profession; his heart was in philosophy. In 373, Augustine and his friend Honoratus fell into the snares of the Manichæans. It seems strange that so great a mind should have been victimized by Oriental vapourings, synthesized by the Persian Mani (215-276) into coarse, material dualism, and introduced into Africa scarcely fifty years previously. Augustine himself tells us that he was enticed by the promises of a free philosophy unbridled by faith; by the boasts of the Manichæans, who claimed to have discovered contradictions in Holy Writ; and, above all, by the hope of finding in their doctrine a scientific explanation of nature and its most mysterious phenomena. Augustine's inquiring mind was enthusiastic for the natural sciences, and the Manichæans declared that nature withheld no secrets from Faustus, their doctor. Moreover, being tortured by the problem of the origin of evil, Augustine, in default of solving it, acknowledged a conflict of two principles. And then, again, there was a very powerful charm in the moral irresponsibility resulting from a doctrine which denied liberty and attributed the commission of crime to a foreign principle.

Once won over to this sect, Augustine devoted himself to it with all the ardour of his character; he read all its books, adopted and defended all its opinions. His furious proselytism drew into error his friend Alypius and Romanianus, his Mæcenas of Tagaste, the friend of his father who was defraying the expenses of Augustine's studies. It was during this Manichæan period that Augustine's literary faculties reached their full development, and he was still a student at Carthage when he embraced error. His studies ended, he should in due course have entered the forum litigiosum, but he preferred the career of letters, and Possidius tells us that he returned to Tagaste to "teach grammar." The young professor captivated his pupils, one of whom, Alypius, hardly younger than his master, loath to leave, him after following him into error, was afterwards baptized with him at Milan, eventually becoming Bishop of Tagaste, his native city. But Monica deeply deplored Augustine's heresy and would not have received him into her home or at her table but for the advice of a saintly bishop, who declared that "the son of so many tears could not perish." Soon afterwards Augustine went to Carthage, where he continued to teach rhetoric.

His talents shone to even better advantage on this wider stage, and by an indefatigable pursuit of the liberal arts his intellect attained its full maturity. Having taken part in a poetic tournament, he carried off the prize, and the Proconsul Vindicianus publicly conferred upon him the corona agonistica. It was at this moment of literary intoxication, when he had just completed his first work on æsthetics, now lost that he began to repudiate Manichæism. Even when Augustine was in his first fervour, the teachings of Mani had been far from quieting his restlessness, and although he has been accused of becoming a priest of the sect, he was never initiated or numbered among the "elect," but remained an "auditor" the lowest degree in the hierarchy. Reason for his disenchantment. First of all there was the fearful depravity of Manichæan philosophy — "They destroy everything and build up nothing"; then, the dreadful immorality in contrast with their affectation of virtue; the feebleness of their arguments in controversy with the Catholics, to whose Scriptural arguments their only reply was: "The Scriptures have been falsified." But, worse than all, he did not find science among them — science in the modern sense of the word — that knowledge of nature and its laws which they had promised him. When he questioned them concerning the movements of the stars, none of them could answer him. "Wait for Faustus," they said, "he will explain everything to you." Faustus of Mileve, the celebrated Manichæan bishop, at last came to Carthage; Augustine visited and questioned him, and discovered in his responses the vulgar rhetorician, the utter stranger to all scientific culture. The spell was broken, and, although Augustine did not immediately abandon the sect, his mind rejected Manichæan doctrines. The illusion had lasted nine years.

But the religious crisis of this great soul was only to be resolved in Italy, under the influence of Ambrose. In 383 Augustine, at the age of twenty-nine, yielded to the irresistible attraction which Italy had for him, but his mother suspected his departure and was so reluctant to be separated from him that he resorted to a subterfuge and embarked under cover of the night. He had only just arrived in Rome when he was taken seriously ill; upon recovering he opened a school of rhetoric, but, disgusted by the tricks of his pupils, who shamelessly defrauded him of their tuition fees, he applied for a vacant professorship at Milan, obtained it, and was accepted by the prefect, Symmachus. Having visited Bishop Ambrose, the fascination of that saint's kindness induced him to become a regular attendant at his preachings. However, before embracing the Faith, Augustine underwent a three years' struggle during which his mind passed through several distinct phases.

At first he turned towards the philosophy of the Academics, with its pessimistic scepticism; then neo-Platonic philosophy inspired him with genuine enthusiasm. At Milan he had scarcely read certain works of Plato and, more especially, of Plotinus, before the hope of finding the truth dawned upon him. Once more he began to dream that he and his friends might lead a life dedicated to the search for it, a life purged of all vulgar aspirations after honours, wealth, or pleasure, and with celibacy for its rule (Confessions, VI). But it was only a dream; his passions still enslaved him. Monica, who had joined her son at Milan, prevailed upon him to become betrothed, but his affianced bride was too young, and although Augustine dismissed the mother of Adeodatus, her place was soon filled by another. Thus did he pass through one last period of struggle and anguish.

Finally, through the reading of the Holy Scriptures light penetrated his mind. Soon he possessed the certainty that Jesus Christ is the only way to truth and salvation. After that resistance came only from the heart. An interview with Simplicianus, the future successor of St. Ambrose, who told Augustine the story of the conversion of the celebrated neo-Platonic rhetorician, Victorinus (Confessions, VIII, i, ii), prepared the way for the grand stroke of grace which, at the age of thirty-three, smote him to the ground in the garden at Milan (September, 386). A few days later Augustine, being ill, took advantage of the autumn holidays and, resigning his professorship, went with Monica, Adeodatus, and his friends to Cassisiacum, the country estate of Verecundus, there to devote himself to the pursuit of true philosophy which, for him, was now inseparable from Christianity.

II. FROM HIS CONVERSION TO HIS EPISCOPATE (386-395)

Augustine gradually became acquainted with Christian doctrine, and in his mind the fusion of Platonic philosophy with revealed dogmas was taking place. The law that governed this change of thought has of late years been frequently misconstrued; it is sufficiently important to be precisely defined. The solitude of Cassisiacum realized a long-cherished dream. In his books "Against the Academics," Augustine has described the ideal serenity of this existence, enlivened only by the passion for truth. He completed the education of his young friends, now by literary readings in common, now by philosophical conferences to which he sometimes invited Monica, and the accounts of which, compiled by a secretary, have supplied the foundation of the "Dialogues." Licentius, in his "Letters," would later on recall these delightful philosophical mornings and evenings, at which Augustine was wont to evolve the most elevating discussions from the most commonplace incidents. The favourite topics at their conferences were truth, certainty (Against the Academics), true happiness in philosophy (On a Happy Life), the Providential order of the world and the problem of evil (On Order) and finally God and the soul (Soliloquies, On the Immortality of the Soul).

Here arises the curious question propounded modern critics: Was Augustine a Christian when wrote these "Dialogues" at Cassisiacum? Until now no one had doubted it; historians, relying upon the "Confessions," had all believed that Augustine's retirement to the villa had for its twofold object the improvement of his health and his preparation for baptism. But certain critics nowadays claim to have discovered a radical opposition between the philosophical "Dialogues" composed in this retirement and the state of soul described in the "Confessions." According to Harnack, in writing the "Confessions" Augustine must have projected upon the recluse of 386 the sentiments of the bishop of 400. Others go farther and maintain that the recluse of the Milanese villa could not have been at heart a Christian, but a Platonist; and that the scene in the garden was a conversion not to Christianity, but to philosophy, the genuinely Christian phase beginning only in 390. But this interpretation of the "Dialogues" cannot withstand the test of facts and texts. It is admitted that Augustine received baptism at Easter, 387; and who could suppose that it was for him a meaningless ceremony?

So too, how can it be admitted that the scene in the garden, the example of the recluses, the reading of St. Paul, the conversion of Victorinus, Augustine's ecstasies in reading the Psalms with Monica were all invented after the fact? Again, as it was in 388 that Augustine wrote his beautiful apology "On the Holiness of the Catholic Church," how is it conceivable that he was not yet a Christian at that date? To settle the argument, however, it is only necessary to read the "Dialogues" themselves. They are certainly a purely philosophical work — a work of youth, too, not without some pretension, as Augustine ingenuously acknowledges (Confessions, IX, iv); nevertheless, they contain the entire history of his Christian formation. As early as 386, the first work written at Cassisiacum reveals to us the great underlying motive of his researches. The object of his philosophy is to give authority the support of reason, and "for him the great authority, that which dominates all others and from which he never wished to deviate, is the authority of Christ"; and if he loves the Platonists it is because he counts on finding among them interpretations always in harmony with his faith (Against the Academics, III, c. x).

To be sure such confidence was excessive, but it remains evident that in these "Dialogues" it is a Christian, and not a Platonist, that speaks. He reveals to us the intimate details of his conversion, the argument that convinced him (the life and conquests of the Apostles), his progress in the Faith at the school of St. Paul (ibid., II, ii), his delightful conferences with his friends on the Divinity of Jesus Christ, the wonderful transformations worked in his soul by faith, even to that victory of his over the intellectual pride which his Platonic studies had aroused in him (On The Happy Life, I, ii), and at last the gradual calming of his passions and the great resolution to choose wisdom for his only spouse (Soliloquies, I, x).

It is now easy to appreciate at its true value the influence of neo-Platonism upon the mind of the great African Doctor. It would be impossible for anyone who has read the works of St. Augustine to deny the existence of this influence. However, it would be a great exaggeration of this influence to pretend that it at any time sacrificed the Gospel to Plato. The same learned critic thus wisely concludes his study: "So long, therefore, as his philosophy agrees with his religious doctrines, St. Augustine is frankly neo-Platonist; as soon as a contradiction arises, he never hesitates to subordinate his philosophy to religion, reason to faith. He was, first of all, a Christian; the philosophical questions that occupied his mind constantly found themselves more and more relegated to the background" (op. cit., 155). But the method was a dangerous one; in thus seeking harmony between the two doctrines he thought too easily to find Christianity in Plato, or Platonism in the Gospel.

More than once, in his "Retractations" and elsewhere, he acknowledges that he has not always shunned this danger. Thus he had imagined that in Platonism he discovered the entire doctrine of the Word and the whole prologue of St. John. He likewise disavowed a good number of neo-Platonic theories which had at first misled him — the cosmological thesis of the universal soul, which makes the world one immense animal — the Platonic doubts upon that grave question: Is there a single soul for all or a distinct soul for each? But on the other hand, he had always reproached the Platonists, as Schaff very properly remarks (Saint Augustine, New York, 1886, p. 51), with being ignorant of, or rejecting, the fundamental points of Christianity: "first, the great mystery, the Word made flesh; and then love, resting on the basis of humility." They also ignore grace, he says, giving sublime precepts of morality without any help towards realizing them.

It was this Divine grace that Augustine sought in Christian baptism. Towards the beginning of Lent, 387, he went to Milan and, with Adeodatus and Alypius, took his place among the competentes, being baptized by Ambrose on Easter Day, or at least during Eastertide. The tradition maintaining that the Te Deum was sung on that occasion by the bishop and the neophyte alternately is groundless. Nevertheless this legend is certainly expressive of the joy of the Church upon receiving as her son him who was to be her most illustrious doctor. It was at this time that Augustine, Alypius, and Evodius resolved to retire into solitude in Africa. Augustine undoubtedly remained at Milan until towards autumn, continuing his works: "On the Immortality of the Soul" and "On Music." In the autumn of 387, he was about to embark at Ostia, when Monica was summoned from this life.

In all literature there are no pages of more exquisite sentiment than the story of her saintly death and Augustine's grief (Confessions, IX). Augustine remained several months in Rome, chiefly engaged in refuting Manichæism. He sailed for Africa after the death of the tyrant Maximus (August 388) and after a short sojourn in Carthage, returned to his native Tagaste. Immediately upon arriving there, he wished to carry out his idea of a perfect life, and began by selling all his goods and giving the proceeds to the poor. Then he and his friends withdrew to his estate, which had already been alienated, there to lead a common life in poverty, prayer, and the study of sacred letters. Book of the "LXXXIII Questions" is the fruit of conferences held in this retirement, in which he also wrote "De Genesi contra Manichæos," "De Magistro," and, "De Vera Religione."

Augustine did not think of entering the priesthood, and, through fear of the episcopacy, he even fled from cities in which an election was necessary. One day, having been summoned to Hippo by a friend whose soul's salvation was at stake, he was praying in a church when the people suddenly gathered about him, cheered him, and begged Valerius, the bishop, to raise him to the priesthood. In spite of his tears Augustine was obliged to yield to their entreaties, and was ordained in 391. The new priest looked upon his ordination as an additional reason for resuming religious life at Tagaste, and so fully did Valerius approve that he put some church property at Augustine's disposal, thus enabling him to establish a monastery the second that he had founded.

His priestly ministry of five years was admirably fruitful; Valerius had bidden him preach, in spite of the deplorable custom which in Africa reserved that ministry to bishops. Augustine combated heresy, especially Manichæism, and his success was prodigious. Fortunatus, one of their great doctors, whom Augustine had challenged in public conference, was so humiliated by his defeat that he fled from Hippo. Augustine also abolished the abuse of holding banquets in the chapels of the martyrs. He took part, 8 October, 393, in the Plenary Council of Africa, presided over by Aurelius, Bishop of Carthage, and, at the request of the bishops, was obliged to deliver a discourse which, in its completed form, afterwards became the treatise "De Fide et symbolo."

Enfeebled by old age, Valerius, Bishop of Hippo, obtained the authorization of Aurelius, Primate of Africa, to associate Augustine with himself as coadjutor. Augustine had to resign himself to consecration at the hands of Megalius, Primate of Numidia. He was then forty two, and was to occupy the See of Hippo for thirty-four years. The new bishop understood well how to combine the exercise of his pastoral duties with the austerities of the religious life, and although he left his convent, his episcopal residence became a monastery where he lived a community life with his clergy, who bound themselves to observe religious poverty. Was it an order of regular clerics or of monks that he thus founded? This is a question often asked, but we feel that Augustine gave but little thought to such distinctions. Be that as it may, the episcopal house of Hippo became a veritable nursery which supplied the founders of the monasteries that were soon spread all over Africa and the bishops who occupied the neighbouring sees. Possidius (Vita S. August., xxii) enumerates ten of the saint's friends and disciples who were promoted to the episcopacy. Thus it was that Augustine earned the title of patriarch of the religious, and renovator of the clerical, life in Africa.

But he was above all the defender of truth and the shepherd of souls. His doctrinal activities, the influence of which was destined to last as long as the Church itself, were manifold: he preached frequently, sometimes for five days consecutively, his sermons breathing a spirit of charity that won all hearts; he wrote letters which scattered broadcast through the then known world his solutions of the problems of that day; he impressed his spirit upon divers African councils at which he assisted, for instance, those of Carthage in 398, 401, 407, 419 and of Mileve in 416 and 418; and lastly struggled indefatigably against all errors. To relate these struggles were endless; we shall, therefore, select only the chief controversies and indicate in each the doctrinal attitude of the great Bishop of Hippo.

Problem of Evil - After Augustine became bishop the zeal which, from the time of his baptism, he had manifested in bringing his former co-religionists into the true Church, took on a more paternal form without losing its pristine ardour — "let those rage against us who know not at what a bitter cost truth is attained. . . . As for me, I should show you the same forbearance that my brethren had for me when I blind, was wandering in your doctrines" (Contra Epistolam Fundamenti, iii). Among the most memorable events that occurred during this controversy was the great victory won in 404 over Felix, one of the "elect" of the Manichæans and the great doctor of the sect. He was propagating his errors in Hippo, and Augustine invited him to a public conference the issue of which would necessarily cause a great stir; Felix declared himself vanquished, embraced the Faith, and, together with Augustine, subscribed the acts of the conference. In his writings Augustine successively refuted Mani (397), the famous Faustus (400), Secundinus (405), and (about 415) the fatalistic Priscillianists whom Paulus Orosius had denounced to him. These writings contain the saint's clear, unquestionable views on the eternal problem of evil, views based on an optimism proclaiming, like the Platonists, that every work of God is good and that the only source of moral evil is the liberty of creatures (De Civitate Dei, XIX, c. xiii, n. 2). Augustine takes up the defence of free will, even in man as he is, with such ardour that his works against the Manichæan are an inexhaustible storehouse of arguments in this still living controversy.

In vain have the Jansenists maintained that Augustine was unconsciously a Pelagian and that he afterwards acknowledged the loss of liberty through the sin of Adam. Modern critics, doubtless unfamiliar with Augustine's complicated system and his peculiar terminology, have gone much farther. In the "Revue d'histoire et de littérature religieuses" (1899, p. 447), M. Margival exhibits St. Augustine as the victim of metaphysical pessimism unconsciously imbibed from Manichæan doctrines. "Never," says he, "will the Oriental idea of the necessity and the eternity of evil have a more zealous defender than this bishop." Nothing is more opposed to the facts. Augustine acknowledges that he had not yet understood how the first good inclination of the will is a gift of God (Retractions, I, xxiii, n, 3); but it should be remembered that he never retracted his leading theories on liberty, never modified his opinion upon what constitutes its essential condition, that is to say, the full power of choosing or of deciding. Who will dare to say that in revising his own writings on so important a point he lacked either clearness of perception or sincerity?

Theory of the Church - The Donatist schism was the last episode in the Montanist and Novatian controversies which had agitated the Church from the second century. While the East was discussing under varying aspects the Divine and Christological problem of the Word, the West, doubtless because of its more practical genius, took up the moral question of sin in all its forms. The general problem was the holiness of the Church; could the sinner be pardoned, and remain in her bosom? In Africa the question especially concerned the holiness of the hierarchy. The bishops of Numidia, who, in 312, had refused to accept as valid the consecration of Cæcilian, Bishop of Carthage, by a traditor, had inaugurated the schism and at the same time proposed these grave questions: Do the hierarchical powers depend upon the moral worthiness of the priest? How can the holiness of the Church be compatible with the unworthiness of its ministers?

At the time of Augustine's arrival in Hippo, the schism had attained immense proportions, having become identified with political tendencies — perhaps with a national movement against Roman domination. In any event, it is easy to discover in it an undercurrent of anti-social revenge which the emperors had to combat by strict laws. The strange sect known as "Soldiers of Christ," and called by Catholics Circumcelliones (brigands, vagrants), resembled the revolutionary sects of the Middle Ages in point of fanatic destructiveness — a fact that must not be lost sight of, if the severe legislation of the emperors is to be properly appreciated.

The history of Augustine's struggles with the Donatists is also that of his change of opinion on the employment of rigorous measures against the heretics; and the Church in Africa, of whose councils he had been the very soul, followed him in the change. This change of views is solemnly attested by the Bishop of Hippo himself, especially in his Letters, xciii (in the year 408). In the beginning, it was by conferences and a friendly controversy that he sought to re-establish unity. He inspired various conciliatory measures of the African councils, and sent ambassadors to the Donatists to invite them to re-enter the Church, or at least to urge them to send deputies to a conference (403). The Donatists met these advances at first with silence, then with insults, and lastly with such violence that Possidius Bishop of Calamet, Augustine's friend, escaped death only by flight, the Bishop of Bagaïa was left covered with horrible wounds, and the life of the Bishop of Hippo himself was several times attempted (Letter lxxxviii, to Januarius, the Donatist bishop).

This madness of the Circumcelliones required harsh repression, and Augustine, witnessing the many conversions that resulted therefrom, thenceforth approved rigid laws. However, this important restriction must be pointed out: that St. Augustine never wished heresy to be punishable by death — Vos rogamus ne occidatis (Letter c, to the Proconsul Donatus). But the bishops still favoured a conference with the schismatics, and in 410 an edict issued by Honorius put an end to the refusal of the Donatists. A solemn conference took place at Carthage, in June, 411, in presence of 286 Catholic, and 279 Donatist bishops. The Donatist spokesmen were Petilian of Constantine, Primian of Carthage, and Emeritus of Cæsarea; the Catholic orators, Aurelius and Augustine. On the historic question then at issue, the Bishop of Hippo proved the innocence of Cæcilian and his consecrator Felix, and in the dogmatic debate he established the Catholic thesis that the Church, as long as it is upon earth, can, without losing its holiness, tolerate sinners within its pale for the sake of converting them. In the name of the emperor the Proconsul Marcellinus sanctioned the victory of the Catholics on all points. Little by little Donatism died out, to disappear with the coming of the Vandals.

So amply and magnificently did Augustine develop his theory on the Church that, according to Specht "he deserves to be named the Doctor of the Church as well as the Doctor of Grace"; and Möhler (Dogmatik, 351) is not afraid to write: "For depth of feeling and power of conception nothing written on the Church since St. Paul's time, is comparable to the works of St. Augustine." He has corrected, perfected, and even excelled the beautiful pages of St. Cyprian on the Divine institution of the Church, its authority, its essential marks, and its mission in the economy of grace and the administration of the sacraments.

The Protestant critics, Dorner, Bindemann, Böhringer and especially Reuter, loudly proclaim, and sometimes even exaggerate, this rôle of the Doctor of Hippo; and while Harnack does not quite agree with them in every respect he does not hesitate to say (History of Dogma, II, c. iii): "It is one of the points upon which Augustine specially affirms and strengthens the Catholic idea.... He was the first [!] to transform the authority of the Church into a religious power, and to confer upon practical religion the gift of a doctrine of the Church." He was not the first, for Dorner acknowledges (Augustinus, 88) that Optatus of Mileve had expressed the basis of the same doctrines. Augustine, however, deepened, systematized, and completed the views of St. Cyprian and Optatus. But it is impossible here to go into detail. (See Specht, Die Lehre von der Kirche nach dem hl. Augustinus, Paderborn, l892.)

The close of the struggle against the Donatists almost coincided with the beginnings of a very grave theological dispute which not only was to demand Augustine's unremitting attention up to the time of his death, but was to become an eternal problem for individuals and for the Church. Farther on we shall enlarge upon Augustine's system; here we need only indicate the phases of the controversy. Africa, where Pelagius and his disciple Celestius had sought refuge after the taking of Rome by Alaric, was the principal centre of the first Pelagian disturbances; as early as 412 a council held at Carthage condemned Pelagians for their attacks upon the doctrine of original sin. Among other books directed against them by Augustine was his famous "De naturâ et gratiâ." Thanks to his activity the condemnation of these innovators, who had succeeded in deceiving a synod convened at Diospolis in Palestine, was reiterated by councils held later at Carthage and Mileve and confirmed by Pope Innocent I (417).

A second period of Pelagian intrigues developed at Rome, but Pope Zosimus, whom the stratagems of Celestius had for a moment deluded, being enlightened by Augustine, pronounced the solemn condemnation of these heretics in 418. Thenceforth the combat was conducted in writing against Julian of Eclanum, who assumed the leadership of the party and violently attacked Augustine. Towards 426 there entered the lists a school which afterwards acquired the name of Semipelagian, the first members being monks of Hadrumetum in Africa, who were followed by others from Marseilles, led by Cassian, the celebrated abbot of Saint-Victor. Unable to admit the absolute gratuitousness of predestination, they sought a middle course between Augustine and Pelagius, and maintained that grace must be given to those who merit it and denied to others; hence goodwill has the precedence, it desires, it asks, and God rewards. Informed of their views by Prosper of Aquitaine, the holy Doctor once more expounded, in "De Prædestinatione Sanctorum," how even these first desires for salvation are due to the grace of God, which therefore absolutely controls our predestination.

In 426 at the age of seventy-two, wishing to spare his episcopal city the turmoil of an election after his death, caused both clergy and people to acclaim the choice of the deacon Heraclius as his auxiliary and successor, and transferred to him the administration of externals. Augustine might then have enjoyed some rest had Africa not been agitated by the undeserved disgrace and the revolt of Count Boniface (427). The Goths, sent by the Empress Placidia to oppose Boniface, and the Vandals, whom the latter summoned to his assistance, were all Arians. Maximinus, an Arian bishop, entered Hippo with the imperial troops.

The holy Doctor defended the Faith at a public conference (428) and in various writings. Being deeply grieved at the devastation of Africa, he laboured to effect a reconciliation between Count Boniface and the empress. Peace was indeed re stablished, but not with Genseric, the Vandal king. Boniface, vanquished, sought refuge in Hippo, whither many bishops had already fled for protection and this well fortified city was to suffer the horrors of an eighteen months' siege. Endeavouring to control his anguish, Augustine continued to refute Julian of Eclanum; but early in the siege he was stricken with what he realized to be a fatal illness, and, after three months of admirable patience and fervent prayer, departed from this land of exile on 8 August, 430, in the seventy-sixth year of his age.

Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430), bishop and Doctor of the Church is best known for his Confessions (401), his autobiographical account of his conversion. The term augustinianism evolved from his writings that had a profound influence on the church.

Augustine was born at Tagaste (now Nigeria) in North Africa on 13 November, 354. His father, Patricius, while holding an official position in the city remained a pagan until converting on his deathbed. His mother, Saint Monica, was a devout Christian. She had had Augustine signed with the cross and enrolled among the catechumens but unable to secure his baptism. Her grief was great when young Augustine fell gravely ill and agreed to be baptised only to withdraw his consent upon recovery, denouncing the Christian faith.

At the encouragement of Monica, his extensive religious education started in the schools of Tagaste (an important part of the Roman Empire) and Madaura until he was sixteen. He was off to Carthage next in 370, but soon fell to the pleasures and excesses of the half pagan city’s theatres, licentiousness and decadent socialising with fellow students. After a time he confessed to Monica that he had been living in sin with a woman with whom he had a son in 372, Adeodatus, (which means Gift of God).

Still a student, and with a newfound desire to focus yet again on exploration of his faith, in 373 Augustine became a confirmed Manichaean, much against his mother’s wishes. He was enticed by its promise of free philosophy which attracted his intellectual interest in the natural sciences. It did not however erase his moral turmoil of finding his faith. His intellect having attained full maturity, he returned to Tagaste then Carthage to teach rhetoric, being very popular among his students. Now in his thirties, his spiritual journey led him away from Manichaeism after nine years because of disagreement with its cosmology and a disenchanting meeting with the celebrated Manichaean bishop, Faustus of Mileve.

Passing through yet another period of spiritual struggle, Augustine went to Italy in 383, studying Neo-platonic philosophy. Enthralled by his kindness and generous spirit, he became a pupil of Ambrose. At the age of thirty-three, the epiphany and clarity of purpose which Augustine had sought for so long finally came to him in Milan in 386 through a vast stream of tears as he lay prostrate under a fig tree. He was baptised by Ambrose in 387 much to the eternal delight of his mother, “..nothing is far from God.” The next event in his life leads to some of the most profound and exquisite writings on love and grief; the death of his mother Monica.

Surrounded by friends, Augustine now returned to his native Tagaste where he devoted himself to the rule in a quasi-monastic life to prayer and studying sacred letters and to finding harmony between the philosophical questions that plagued his mind and his faith in Christianity. He was ordained as priest in 391.

For the next five years Augustine’s priestly life was fruitful, consisting of administration of church business, tending to the poor, preaching and writing and acting as judge for civil and ecclesiastical cases, always the defender of truth and a compassionate shepherd of souls. At the age of forty-two he then became coadjutor-bishop of Hippo. From 396 till his death in 439, he ruled the diocese alone. At that point the Roman Empire was in disintegration, and at the time of his death the Vandals where at the gates of Hippo. 28 August, 430, in the seventy-sixth year of his age Augustine succumbed to a fatal illness. His relics were translated from Sardinia to Pavia by Luitprand, King of the Lombards. Saint Augustine is often depicted as one of the Four Latin Doctors in many paintings, frescoes and stained glass throughout the world. “Unhappy is the soul enslaved by the love of anything that is mortal.” Saint Augustine. The cult of Augustine formed swiftly and was widespread. His feast is 28 August.