Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2006

Astro-Rayological

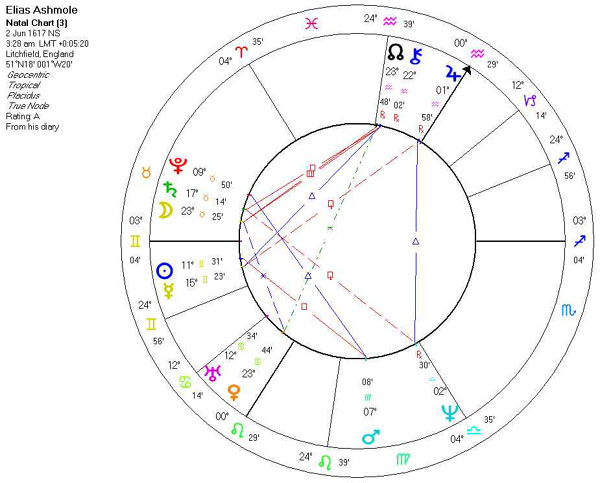

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

Writes Elias Ashmole, "And certainly he to whom the whole course of Nature lyes open rejoyceth not so much that he can make Gold or Silver or the Divells [devils] to become subject to him, as that hee sees the Heavens open, the Angells of God Ascending and Descending, and that his own name is fairely written in the Book of Life" ("Prolegomenia," in Theatrum Chemicum Bitannicum [London, 1652]).

On 13th May 1653, Backhouse "told me, in syllables, the true matter of the philosopher's stone, which he bequeathed to me as a legacy."

Elias Ashmole (May 23, 1617–May 18, 1692) was an antiquarian, collector, politician and student of astrology and alchemy. He supported the royalist side during the English Civil War, and at the restoration of Charles II he was rewarded with several lucrative offices. Throughout his life he was an avid collector of books, manuscripts, curiosities and other artifacts, most of which he donated to Oxford University to create the Ashmolean Museum.

Solicitor and royalist

Ashmole was born in Lichfield. His family had been prominent, but its fortunes had declined somewhat by the time of Ashmole's birth. His father, Simon Ashmole, was a soldier and a saddler; his mother Anne was a relative of James Pagit, a Baron of the Exchequer. Ashmole attended Lichfield Grammar School and became a chorister at Lichfield Cathedral. In 1638, with the help of Pagit, he became a solicitor. He enjoyed a successful practice in London, and married Eleanor Mainwaring, a member of poor but aristocratic family, who died only three years later. Still in his early twenties, Ashmole had taken the first steps towards status and wealth.Ashmole supported the side of Charles I in the Civil War. At the outbreak of fighting in 1642, he left London for the house of his father-in-law, Peter Mainwaring, at Smallwood in Cheshire. There he lived a retired life until 1644, when he was appointed King's Commissioner of Excise at Lichfield. Soon afterwards he was given a military post at Oxford, where he devoted most of his time to study and acquired a deep interest in alchemy, astrology and magic. He studied physics and mathematics at Brasenose College, though he did not formally enter as a student. In late 1645, he left Oxford to accept the position of Commissioner of Excise at Worcester. (Excise Commissioners set taxes on specific locally produced commodities; at that time, the division between official and personal property was not as rigorously observed as it is today, so such offices could be very lucrative to their holders.)

Ashmole was given the additional military posts of Captain of the Horse and Comptroller of Ordnance, though he seems never to have participated in any fighting. After the Royalist defeat of 1646, he retired again to Cheshire. During this period he was admitted as a Freemason (the earliest documented admission of a Freemason in England), though he seems to have participated in Masonic activity on only one other occasion.

In 1649 he married Mary, Lady Mainwaring (nee Forster), a wealthy thrice-widowed woman twenty years his senior. She was a relative by marriage of his first wife's family and the mother of grown children. The marriage took place over the opposition of the bride's family, and it did not prove to be harmonious: Lady Mainwaring filed an unsuccessful suit for separation and alimony in 1657. The match, did, however, leave Ashmole wealthy enough to pursue his interests without concern for his livelihood.

Alchemy and the Tradescant Collection

During the 1650s, Ashmole devoted a great deal of energy to the study of alchemy. In 1650 he published Fasciculus Chemicus under the anagrammatic pseudonym James Hasholle. This work was an English translation of two Latin alchemical works, one by Arthur Dee. In 1652, he published his most important alchemical work, Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum, an extensively annotated compilation of alchemical poems in English. The book preserved and made available many works that had previously existed only in privately-held manuscripts. It was avidly studied by other alchemists.In 1653, the alchemist William Backhouse, who had made Ashmole his alchemical "son," confided the secret of the Philosopher's Stone to Ashmole when he believed himself to be close to death. (The Philosopher's Stone was a substance or object that had the power to convert base metals to gold, among other mystical virtues: its discovery was one of the key goals of European alchemists.) Ashmole is said to have passed the secret on to Robert Plot, the first keeper of the Ashmolean Museum. Ashmole published his final alchemical work, The Way to Bliss, in 1658. There is no evidence of him personally carrying out any actual experiments (or "operations," in the alchemical jargon of the time).

Ashmole met the botanist and collector John Tradescant around 1650. Tradescant had, with his father, built up a vast and renowned collection of exotic plants, mineral specimens and other curiosities from around the world. Ashmole helped Tradescant catalogue his collection in 1652, and in 1656 he financed the publication of the catalogue, the Musaeum Tradescantianum. In 1659, Tradescant, who had lost his only son and heir ten years earlier, legally deeded his collection to Ashmole. Under the agreement, Ashmole would take possession at Tradescant's death. When Tradescant did die in 1662, his widow Hester contested the deed, but the matter was settled in Chancery in Ashmole's favor two years later.

Restoration

With the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, Ashmole's loyalty was richly rewarded. He was given the office of Comptroller for the Excise in London, and later was made a Commissioner of Surinam and the Accountant General of the Excise, a position that made him responsible for a large portion of the king's revenue. These posts yielded him considerable income as well as considerable patronage power.Ashmole became one of the founding members of the Royal Society in 1661, but he was never an active member. His most significant appointment, though, was to the College of Arms as Windsor Herald in 1660. In this position he devoted himself to the study of the history of the Order of the Garter, which had been a special interest of his since the 1650s. In 1672, he published the fruits of his years of research, The Institution, Laws and Ceremonies of the Most Noble Order of the Garter, a lavish folio with illustrations by Wenceslaus Hollar. Ashmole performed the heraldic and genealogical work of his office scrupulously, and he was considered the leading authority on court protocol and ceremonial.

In 1668, Lady Mainwaring died, and Ashmole married the much younger daughter of his friend and fellow herald, the antiquarian Sir William Dugdale. In 1675 he resigned as Windsor Herald, perhaps because of factional strife within the College of Arms. He was offered the post of Garter King of Arms, but he turned it down in favor of Dugdale.

Though his interest in alchemy cooled somewhat after the 1650s, he never lost interest in magic and astrology. He was often consulted on astrological matters by Charles II and members of his court. In 1672, he acquired some of John Dee's previously unknown spiritual diaries describing his conferences with angels. He devoted much time and energy to the intensive study of these manuscripts, and contemplated writing a biography of Dee.

Ashmole's health began to deteriorate in the 1680s, and though he would hold his excise office until he died, he became much less active in affairs. He began to collect notes on his life in diary form to serve as source material for a biography; although the biography was never written, these notes are a rich source of information on Ashmole and his times. He died in Lambeth on May 18, 1692. He was buried at South Lambeth Church. Ashmole bequeathed his library and his priceless manuscript collection to Oxford.

Michael Hunter, in his entry on Ashmole for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, concluded that the most salient points of Ashmole's character were his ambition and his heirarchical vision of the world--a vision that unified his royalism and his interests in heraldry, genealogy, ceremony and even astrology and magic. He was as successful in his legal, business and political affairs as we was in his collecting and scholarly pursuits. His antiquarian work is still considered valuable, and his alchemical publications, especially the Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum, preserved many works that might otherwise have been lost. He formed several close and long-lasting friendships, with John Aubrey for example, but, as Richard Garnett has observed, "Acquisitiveness was his master passion."

Born: 23rd May 1617

at Lichfield, Staffordshire Windsor Herald

Died: 18th May 1692 at South Lambeth, SurreyElias Ashmole, "the greatest virtuoso and curioso that ever was known or read of in England before his time," was born at Lichfield on 23rd May 1617. His father, though following the trade of a saddler, was a man of good family, who had seen much service in Ireland. His mother, whose maiden name was Bowyer, was nearly related to James Pagitt, a Baron of the Exchequer. A childhood friendship with Pagitt's son procured Elias' reception into the judge's family, after having received a fair education at Lichfield Grammar School, and as a chorister in the Cathedral.

Through the patronage of Baron Pagitt, he became a solicitor in 1638, "and had indifferent good practice." In the same year, he married Eleanor Mainwaring, of Smallwood in Cheshire, who died suddenly in 1641. In 1642, having embraced the Royalist side in the Civil War, he left London and retired into Cheshire and, in 1644, was appointed by the King as Commissioner of Excise at Lichfield. Business connected with this employment brought him to Oxford, where he was long detained soliciting the Royalist Parliament assembled in that city. There, he made the acquaintance of Captain (afterwards Sir) George Wharton, who procured him a commission in the ordnance, and imbued him with the love of astrology and alchemy which, next to his antiquarianism, became the leading feature of his intellectual character. He entered himself at Brasenose College and studied physics and mathematics; but, about the end of the year, became Commissioner of Excise at Worcester, to which he soon added the employments of Captain of Horse and Controller of the Ordnance. In July 1646, Worcester, however, surrendered to the Parliament, and Ashmole again retired into Cheshire.

In the October, Elias came to London and mixed much in astrological circles, becoming acquainted with Lilly and Booker, and finding himself a guest at 'the mathematical feast at the White Hart.' He was also one of the earliest English Freemasons, having been initiated in or about 1646, in which year the first formal meeting of the body in England was held. His marriage must have been prudent or his employments profitable for, about this time, "it pleased God to put me in mind that I was now placed in the condition I had always desired, which was that I might be enabled to live to myself and studies without being forced to take pains for a livelihood in the World."

This did not, however, prevent his seeking to improve his fortunes still further by marriage with a lady twenty years older than himself. Mary Forster from Aldermaston Court was the widow of three husbands, the mother of grown-up sons and, as Lady Mainwaring, was, in all probability, a relative, through her last husband, of Ashmole's first wife. On 1st March 1647, "I moved the Lady Mainwaring in the way of marriage, and received a fair answer, though no condescension." In July, the lady's second son, Humphrey Stafford, disapproving of the match, "broke into my chamber, and had like to have killed me." He was not deterred, however, from prosecuting his suit, the progress of which is amusingly recorded in his diary. At length, on 16th November 1649, his perseverance was triumphant, and he "enjoyed his wife's estate, though not her company for altogether"; and notwithstanding family jars, subpoenas, sequestrations and frequent sicknesses, all faithfully noted, he vigorously pushed forward his studies in astrology, chemistry and botany.

In 1650, Ashmole edited an alchemical work by Dr. Dee, together with an anonymous tract on the same subject, under the anagram of James Hasolle. In 1652, he published the first volume of his 'Theatruin Chemicum,' a collection of ancient metrical treatises on alchemy. He procured his friend Wharton's deliverance from prison and made him steward of the estates, centred on Bradfield in Berkshire, which he had acquired by his second marriage. He also formed the acquaintance of William Backhouse of Swallowfield Park, a venerable Rosicrucian, who called him son, and "opened himself very freely touching the great secret;" as well as that of John Tradescant, keeper of the botanic garden at Chelsea, an intimacy which has indirectly contributed more than anything else to his celebrity with posterity. He studied Hebrew, engraving and heraldry, and manifested, in every way, an insatiable curiosity for knowledge, justifying Selden's opinion of him as one "affected to the furtherance of all good learning." On 13th May 1653, Backhouse "told me, in syllables, the true matter of the philosopher's stone, which he bequeathed to me as a legacy." But Ashmole has omitted to bequeath it to us. His domestic troubles came to a head in October 1657, when his wife's petition for a separation and alimony, though fortified by eight hundred sheets of depositions, was dismissed by the court and she returned to live with him.

The Restoration marks a great turning point in his life. His loyalty had entitled him to Charles II's favour and, being introduced to the King by no less influential a person than Chiffinch, he was appointed Windsor Herald "and had Henry VIII's closet assigned for my use." From this time, antiquarian pursuits predominated with him and we hear comparatively little of astrology, in which, however, he never lost his belief or interest, and nothing of alchemy. His favour at court continued to grow and places were showered upon him. He successively became commissioner, controller, and accountant-general of excise, and held, at the same time, the employments of commissioner for Surinam and controller of the White office. He was, about this time, engaged in litigation with the widow of his old friend, Tradescant, who had bequeathed his museum to him. A friendly arrangement was, at length, concluded and Ashmole became possessed of the curiosities which formed the nucleus of the institution by which he is best remembered. In 1668, his wife died and, in the course of the same year, he married a much younger lady, the daughter of his friend, the herald, Dugdale. All this time, he was diligently engaged upon his great work, the 'Institution, Laws and Ceremonies of the Order of the Garter,' which was published in 1672 and brought him many tokens of honour, both from his own and foreign countries. It is certainly a noble example of antiquarian zeal and research. He, soon afterwards, retired from his post as Windsor Herald, receiving a pension of £400, secured upon the paper duty; and he subsequently declined the appointment of Garter King-at-Arms in favour of his father-in-law, Sir William Dugdale.

In 1677, Ashmole determined to bestow the museum he had inherited from Tradescant, with his own additions to it, upon the University of Oxford, on condition of a suitable building being provided for its reception. The gift was accepted on these terms, and the collection was removed to Oxford upon the completion of the building in 1682, Dr. Plot being appointed curator. According to Anthony Wood, the curiosities filled twelve wagons. Ashmole quaintly notes in his diary, for 17th February 1683, "The last load of my rarities was sent to the barge, and this afternoon I relapsed into the gout." In 1685, he was invited to represent his native city in Parliament, but desisted from his candidature to gratify King James II. In 1690, he was magnificently entertained by the University of Oxford, which had conferred upon him the degree of MD. He ultimately also bequeathed his library to this institution. It was invaluable as regards manuscripts but equally so in printed books until damaged by a fire at the Temple in 1679, which had also destroyed his collection of medals. He closed his industrious and prosperous life on 18th May 1692, and is interred in South Lambeth Church under a black marble slab with a Latin inscription, promising that his name shall endure as long as his museum.

The Ashmolean Museum, though really formed by Tradescant, has indeed secured its donor a celebrity which he could not have obtained by his writings. Ashmole was nevertheless no ordinary man. His industry was most exemplary, he was disinterestedly attached to the pursuit of knowledge, and his antiquarian researches, at all events, were guided by great good sense. His addiction to astrology was no mark of weakness of judgment in that age. He can hardly have been more attached to it than Dryden or Shaftesbury, but he had more leisure and perseverance for its pursuit. Alchemy, he seems to have quietly dropped. He appears in his diary as a man by no means unfeeling or ungenerous, constant and affectionate in his friendships, and placable towards his adversaries. He had evidently, however, a very keen eye to his own interest, and acquisitiveness was his master passion. His munificence, nevertheless, speaks for itself, and was frequently exercised on unlooked-for occasions, as when he erected monuments to his astrological friends, Lilly and Booker. He was also a benefactor to his native city.

Ashmole's principal work is his 'Institution, Laws, and Ceremonies of the Order of the Garter' (1672), one of those books which exhaust the subject of which they treat and leave scope only for supplements. The edition of 1693 is a mere reprint; but in 1715 a new edition was published under the title of 'The History of the Order of the Garter,' with a continuation by T. Walker. 'The Antiquities of Berkshire, with a particular account of the Castle, College and Town of Windsor,' was published in 1719, and again in 1736. It consists merely of Ashmole's notes during his official visitation as herald, and the genealogical papers transcribed by him; but these form together a very copious collection. It is prefaced by a memoir of the author. His own memoirs, drawn up by himself by way of his diary, were published in 1717, and reprinted along with the autobiography of his friend Lilly in 1774. They are a quaint and curious record, narrating matters of great personal importance to him in the same dry style as the most trivial particulars of big numerous ailments: how he cured himself of an ague by hanging three spiders about his neck and how, on the ever-memorable 14th February 1677, "I took cold in my right ear." His alchemical works are merely editions or reprints and the only one of importance is the 'Theatrum Chemicum' (1652), which contains twenty-nine old English poems on the subject, some very curious. The extent of his collections in genealogy, heraldry, local and family history, astrology and alchemy, may be estimated from the admirable catalogue of Mr. W. H. Black and the index by Messrs. Macray and Gough (1845-66).

____________________________________

Elias Ashmole was a chemist and antiquarian of the late 1600s with connections at Oxford. Some sources have reckoned him to be the first person whose name is recorded as having been made a speculative mason on October 16, 1646 while other sources now propose Robert Moray on May 20, 1641. Neither are identified as the first speculative masons in history — only the first whose names are known.

Ashmole wrote his autobiography, published in London by Davies in 1774, with excerpts reprinted in 1966; Clarendon Press, Oxford. Ashmole included in diary materials of the time reference to his having been a member of a masonic lodge. The dates for these meetings are placed at 16 October 1646, and again on 11 March 1682. An introductory article can be found in A Freemasons Guide and Compendium by Bernard E. Jones and there are substantial articles in the Transactions of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge No 2076 UGLE.

Elias Ashmole's father, Simon Ashmole, was an artisan and a saddler, but he spent more time as a soldier in Ireland and on the continent. Elias implies that he plunged the family into poverty although he did inherit a house from him.

He was educated at Lichfield grammar school with legal training in London, 1633-8. Ashmole studied in Oxford in 1645, and was a member of Brasenose College. He took no degree, but he must have developed a considerable affection for the university, as his later benefaction testifies. Oxford conferred an M.D. on him in 1669.

Raised Anglican with a strong interest in astrology and alchemy, as well as botany. In alchemy he published Fasciculus chemicus (1650), Theatrum chemicum britannicum (1652), and The Way to Bliss (1658). Ashmole later became a simpler in Oxford and developed a fair knowledge of plants.

In 1633 James Pagit, Baron of the Exchequer, whose second wife was the sister of Ashmole's mother, brought him to London to live in his house and continue his education in music. Ashmole studied law with Pagit's sons. It seems manifest that the Pagit connection made possible Ashmole's first marriage above his station.

In 1640 Lord Keeper Finch employed him for a time until Finch was forced to flee the country. Apparently Baroness Kinderton, whom he met through his wife's family, who were gentry, rather adopted Ashmole, and Peter Venables, Baron Kinderton, became his patron.

Ashmole established a law practice in 1638, and for a few years law was his principal means of support. His marrige of 1638 may have provided him with independent means, although this is unclear. Josten thinks that there was no dowry. However, it is worth of note that she was a spinster fourteen years older than Ashmole and from a family of prosperous gentry. In any case, this first wife died in 1641.

During the early forties Ashmole successfully insinuated himself into royalist circles in Oxford. The King, in 1645 inserted his name in the commission instead of that of one John Hanslopp who had originally been appointed.

A royalist in the Civil War, he was appointed by Charles I to collect the excise in Staffordshire in 1644. Appointed commissioner, receiver and registrar of Excise of Worcester, 1645, and Controller and assistant Master of Ordnance in Worcester, 1646.

In 1649 he married a well-to-do widow, Lady Manwaring, who was twenty years his senior; it was her fourth marriage. Her estate established Ashmole's fortunes, even though he ceased to receive the income from her estate after her death in 1668. In every way except for Ashmole's finances the marriage was a disaster.

With the Restoration Ashmole's fortunes really looked up. He was appointed Comptroller and Auditor of the Excise and continued with the Excise until his death. Charles also appointed him Windsor Herald in the same year 1660. He was also appointed Secretary and Clerk of the Courts of Surinam (duties and recompense unknown).

About 1660 he became primarily an antiquarian. He published quite a few books in that field and gathered a collection that he gave to Oxford, along with Tradescant's collection, which had been given to him.

Charles II granted him the position of Comptroller and Auditor of the Excise for the city of London in September of 1660, and Comptroller of the entire Excise in October of the same year. This position gave him more than enough money for living. The King also granted him the office of Windsor Herald and full power and authority to keep accounts of all entries, receipts and payments. He was given the right to peruse, to collect, and to transcribe any documents he might wish to use in his work. His position in the Herald's office was strengthened by a royal warrant in the October of 1660 which granted him precedence over the others newly appointed. In 1661 the King also made him Secretary and Clerk of the Courts of Surinam for life. Along with his offices Ashmole performed various commissions for Charles, such as caring for the King's medals.

Ashmole dedicated his book on the Garter (The Institutions, Laws, and Ceremonies of the Most Noble Order of the Garter, 1672) to Charles II, and gave the first presentation copy, richly bound, to the King. Charles granted him a pension of 400 pounds from the customs on paper. In the presentation copies to six foreign princes who were members of the order, Ashmole inserted specially printed dedications to them. From these came gifts of a gold chain and medal (the King of Denmark) and a similar gift from the Elector of Brandenberg. The other rulers also acknowledged the gift.

In 1677 Ashmole was offered the post of Garter King at Arms; he arranged for it to be conferred instead on his then father-in-law (by his third marriage), William Dugdale.

When his second marriage made him wealthy, Ashmole became something of a patron himself —for example to George Wharton, a fellow royalist and astrologer, who dedicated a book to him in 1652. In 1656 Nathaniel and Thomas Hodges dedicated a translation of Maier's Themis aurea to Ashmole. Also a book on astrology in 1657 was dedicate to him, and in 1655 one on plants. And in fact there were quite a few more dedications throught the rest of his life. In 1682 or 83 he bequeathed the Tradescant collection, which he had received, together with his own collection to Oxford - the initial source of the Ashmolean Museum.

He was deeply interested in the medicinal uses of plants and a member of the Royal Society in 1661, although not active.

In 1677, Ashmole determined to bestow the museum he had inherited from Tradescant, with his own additions to it, upon the University of Oxford, on condition of a suitable building being provided for its reception. The gift was accepted on these terms, and the collection was removed to Oxford upon the completion of the building in 1682, Dr. Plot being appointed curator. According to Anthony Wood, the curiosities filled twelve wagons. Ashmole quaintly notes in his diary, for 17th February 1683, "The last load of my rarities was sent to the barge, and this afternoon I relapsed into the gout."