Marc Antony

Copyright Michael D. Robbins 2006

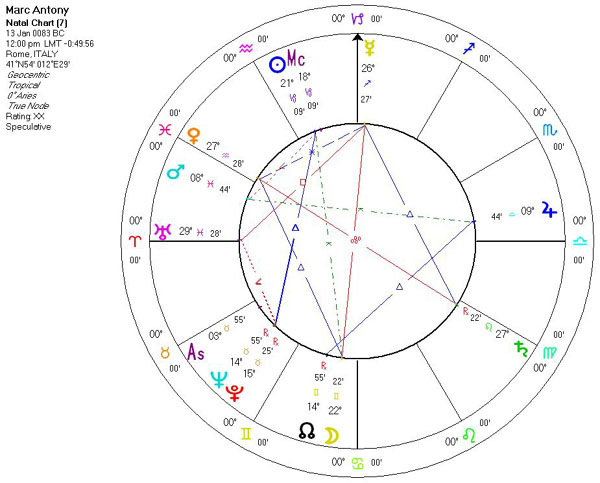

Astro-Rayological

Interpretation & Charts

Quotes

Biography

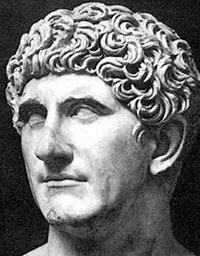

Images and Physiognomic Interpretation

I come here not to praise Caesar.

Oh what a fall was there my countrymen!

A big loveable teddy bear of a man, Marc Antony was Caesar's most loyal supporter. He defended Caesar in a Senate that much preferred Caesar's rival, Pompey. After Pompey's defeat, Caesar left Marc Antony in charge of affairs in Rome.

Upon Caesar's assassination by pro-Republican conspirators Brutus and Cassius and many other senators, Antony so roused the populace that Brutus and Cassius fled Rome for their own safety. But the popular image of Antony giving an eloquent speech at Caesar's funeral is not quite accurate. Instead, in a brilliant stroke, he used the Senate's own words to crush support for a return to a Senate-controlled republic. He simply ordered that the Senate's proclamations declaring Caesar dictator-for-life and granting him the Senate's protection be read at the funeral, adding only a few words of his own. But that was quite enough.

His next move was not so successful. He tried to thwart the efforts of Caesar's heir, Octavian, to collect his political inheritance. Octavian reacted by raising an army among Caesar's veterans and chasing Antony from Rome. He also allied himself with the famous orator, Cicero, though it's not clear whether the idea was Cicero's (who despised Antony) or Octavian's. In any case, Cicero won Octavian the support of the Senate, and Octavian led an army to attack Antony in Gaul.

Instead of fighting, though, they talked over their differences. They agreed to a power sharing arrangement that left Antony, Octavian, and a relatively unimportant fellow named Lepidus in charge, forming the so-called "Second Triumvirate" (the first being Crassus, Pompey, and Caesar). This proved unfortunate for Cicero. As part of the deal, Antony asked that Cicero be executed, and Octavian readily agreed. This probably should have alerted Antony that Octavian wasn't the most reliable of friends.

The first order of business after killing Cicero was to deal once and for all with Caesar's assassins, who still controlled Rome's eastern provinces. Antony and Octavian's armies made short work of it, and both Brutus and Cassius were soon history. Things got a bit rocky between Antony and Octavian after that, but once again they renewed the Triumvirate, this time giving Octavian the west, Antony the east, and Lepidius the African provinces. It was during this period that Herod I gained Antony's assistance in defeating the last of the Hasmonean rulers of Judaea.

Antony then got cozy with Caesar's former lover, Cleopatra VII, in Egypt. After a disastrous campaign against the Parthians, Antony retreated to Egypt, and appeared content to play house with Cleo. When the Second Triumvirate expired in 33 BCE, Octavian used Antony's relationship with Cleopatra for its propaganda value to undermine Antony's support.

About this coin: After the collapse of the Second Triumvirate, denarii like this one were minted by legions loyal to Marc Antony to pay the troops. They featured a war galley on the obverse and a legionary eagle ("Bird on a Stick") flanked by two legionary standards on the reverse. They were typically poorly struck and made of relatively low-grade silver.

Octavian declared war against Egypt in 31 BCE. It came as no surprise to anyone that Antony came in on the side of Egypt. They met at Actium on September 2, 31 BCE, in a great sea battle, and Octavian's forces eventually won, though it was close. Antony and Cleopatra fled to Egypt, but Antony decided that the cause was lost and committed suicide. Cleopatra did the same shortly thereafter, once she decided that she would not be able to successfully ply her charms on Octavian.

Marcus Antonius (Latin: M•ANTONIVS•M•F•M•N¹) (c. 83 BC – August 30 BC), known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general. He was an important supporter of Julius Caesar as a military commander and administrator. After Caesar's assassination, Antony allied with Octavian and Marcus Amelius Lepidus to form the second triumvirate. The triumvirate ended in 33 BC, and Antony committed suicide with Cleopatra in 30 BC.

Antony was born in Rome around 83 BC. His father was his namesake, Marcus Antonius Creticus, the son of the great rhetorician Marcus Antonius Orator executed by Gaius Marius' supporters in 86 BC. Through his mother Julia Caesaris, he was a distant cousin and relative of Julius Caesar. His father died at a young age, leaving him and his brothers, Lucius and Gaius, to the care of his mother. Julia Antonia (known in sources by her married name, to distinguish from the other Julias) then married Publius Cornelius Lentulus Sura, a politician involved in and executed during the Catiline conspiracy of 63 BC.

Antony's early life was characterized by a lack of parental guidance. According to historians like Plutarch, he spent his teenage years roaming through Rome with his brothers and friends (Publius Clodius Pulcher among them). Together, they embarked on a rather wild sort of life, frequenting gambling houses, drinking too much, and involving themselves in scandalous love affairs. Plutarch mentions the rumour that before Antony reached 20 years of age, he was already indebted the sum of 250 talents (equivalent to several million dollars).

After this period of recklessness, Antony went to Greece to study rhetoric. During this visit, he joined the cavalry in the Roman legions of the proconsul Aulus Gabinius en route to Syria. In the ensuing campaign, he demonstrated his talents as a cavalry commander and distinguished himself with bravery and courage. It was during this campaign that he first visited Egypt and Alexandria.

In 54 BC, Antony became a member of the staff of Julius Caesar's armies in Gaul. He again proved to be a competent military leader in the Gallic wars, but his personality caused instability wherever he went. Caesar himself was said to be frequently irritated by his behaviour.

Nevertheless, Antony became a wholehearted Julius Caesar supporter, and he dedicated his year as tribune of the plebians in 50 BC to his cause. Caesar's two proconsular commands, during a period of 10 years, were expiring, and the general wanted to return to Rome for the consular elections. But resistance from the conservative faction of the Roman senate, led by Pompey, demanded that Caesar resign his proconsulship and the command of his armies before he be allowed to seek re-election to the consulship. This he could not do, as such an act would leave him a private citizen--and therefore open to prosecution for his acts while proconsul--in the interim between his proconsulship and his second consulship; it would also leave him at the mercy of Pompey's armies. Antony proposed that both generals lay down their commands. The idea was rejected, and Antony resorted to violence, ending up expelled from the senate. He left Rome, joining Caesar, who had led his armies to the banks of the Rubicon, the river that marked the southern limit of his proconsular authority. With all hopes of a peaceful solution for the conflict with Pompey gone, Caesar led his armies across the river into Italy and marched on Rome, starting the last Republican civil war. During the civil war, Antony was Caesar's second in command. In all battles against the Pompeians, Antony led the left wing of the army, a proof of Caesar's confidence in him.

When Caesar became dictator, Antony was made master of the horse, the dictator's right hand man, and in this capacity remained in Italy as the peninsula's administrator in 47 BC, while Caesar was fighting the last Pompeians, who had taken refuge in the African provinces. But Antony's skills as administrator were a poor match to those as general. Conflict soon arose, and, as on other occasions, Antony resorted to violence. Hundreds of citizens were killed and Rome herself descended into a state of anarchy. Caesar was most displeased with the whole affair and removed Antony from all political responsibilities. The two men did not see each other for two years. Reconciliation arrived in 44 BC, when Antony was chosen as partner for Caesar's fifth consulship.

Whatever conflicts existed between the two men, Antony remained faithful to Caesar at all times. In February of 44 BC, during the Lupercalia festival, Antony publicly offered Caesar a diadem. This was an event fraught with meaning: a diadem was a symbol of a king, and in refusing it, Caesar demonstrated that he did not intend to assume the throne.

On March 15, 44 BC (the Ides of March), Julius Caesar was assassinated by a group of senators, led by Gaius Cassius Longinus and Marcus Junius Brutus. In the turmoil that surrounded the event, Antony escaped Rome dressed as a slave, fearing that the dictator's assassination would be the start of a bloodbath among his supporters. When this did not occur, he soon returned to Rome, discussing a truce with the assassins' faction. For a while, Antony, as consul of the year, seemed to pursue peace and the end of the political tension. Following a speech by Marcus Tullius Cicero in the Senate, an amnesty was agreed for the assassins. Then came the day of Caesar's funeral. As Caesar's ever-present second in command, partner in consulship and cousin, Antony was the natural choice to make the funeral eulogy. In his speech, he sprang his accusations of murder and ensured a permanent breach with conspirators. Showing a talent for rhetoric and dramatic interpretation, Antony snatched the toga from Caesar's body to show the crowd the scars from his wounds. That night, the Roman populace attacked the assassins' houses, forcing them to flee for their lives.

The death of Caesar had left an open space in Rome's politics. The Republic was dying, and yet another civil war was starting. It was then that Octavian, Caesar's great nephew and adopted son, emerged on the political scene. As heir of Caesar's name and estate, he had great political potential due to the esteem of the population and the loyalty of the legions. He was also very willing to fight for power with the other two main contestants: Antony himself and Lepidus. After a few months of difficult negotiations, the three men agreed to share the power as the second triumvirate. The Triumvirs for the Organization of the People gained official recognition by the Lex Titia, a law passed by the Assembly in 43 BC, which granted them virtually all powers for a period of five years. To solidify the alliance, Octavian married Clodia, Antony's step-daughter. The triumvirs then set to pursue the assassins' faction, who had fled to the East, and to murder the conspirators' supporters who remained in Rome. Cicero was the most famous victim of these violent days; knowing that Antony had a grudge against him, the writer committed suicide before they could kill him. (Livy, however, writes that he merely refused to resist the executioners.) Antony and his wife Fulvia did not spare the body: Cicero's head and hands were posted in the rostra, with his tongue pierced by Fulvia's golden hairpins. After the twin battles at Philippi and the suicides of Brutus and Cassius, no one else would defy the triumvirate's power.

With the political and military situations dealt with, the triumvirs divided the Roman world among themselves. Lepidus took control of the western provinces, and Octavian remained in Italy with the responsibility of securing lands for the veteran soldiers—an important task, since the loyalty of the legions depended heavily on this promise. As for Antony, he went to the Eastern provinces, to pacify yet another rebellion in Judaea and attempt to conquer the Parthian Empire. During this trip, he met Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt in Tarsus, in 41 BC, and became her lover.

Meanwhile, in Italy, the situation was not pacified. Octavian's administration was not appeasing, and a revolt was about to occur. Moreover, he divorced Clodia, giving a curious explanation: she was annoying. The leader of this revolt was Fulvia, the wife of Antony, a woman known to history for her political ambition and tempestuous character. She feared for her husband's political position and was not keen to see her daughter put aside. Assisted by Lucius Antonius, her brother-in-law, Fulvia raised eight legions with her own money. Her army invaded Rome, and for a while managed to create problems for Octavian. However, in the winter of 41–40 BC, Fulvia was besieged in Perusia and forced to surrender by starvation. Fulvia was exiled to Sicyon, where she died while waiting for Antony's arrival.

Fulvia's death was providential. A truce with Octavian was negotiated and reinforced by Antony's marriage to Octavia, Octavian's beloved sister. This peace, known as the Treaty of Brundisium, reinforced the triumvirate and allowed Antony to finally prepare his long awaited campaign against the Parthians.

With this military purpose on his mind, Antony sailed to Greece with his new wife. But the rebellion in Sicily of Sextus Pompeius, the last of the Pompeians, kept the army promised to Antony in Italy. With his plans again severed, Antony and Octavian quarreled again. This time with the help of Octavia, a new treaty was signed in Tarentum in 38 BC. The triumvirate was renewed for a period of another five years (ending in 33 BC) and Octavian promised again to send legions to the East.

But by now, Antony was skeptical of Octavian's true support of his Parthian cause. Leaving Octavia pregnant of her second Antonia in Rome, he sailed to Alexandria, where he expected funding from Cleopatra, the mother of his twins. The queen of Egypt loaned him the money he needed for the army, but the campaign proved a disaster. After a series of defeats in battle, Antony lost most of his Egyptian army during a retreat through Armenia in the peak of winter.

Meanwhile in Rome, the triumvirate was no more. Lepidus was forced to resign after an ill-judged political move. Now in sole power, Octavian was occupied in wooing the traditional Republican aristocracy to his side. He married Livia and started to attack Antony in order to raise himself to power. He argued that Antony was a man of low morals to have left his faithful wife abandoned in Rome with the children to be with the promiscuous queen of Egypt. Antony was accused of everything, but most of all, of "becoming native", an unforgivable crime to the proud Romans. Several times Antony was summoned to Rome, but remained in Alexandria with Cleopatra and her funds.

Again with Egyptian money, Antony invaded Armenia, this time successfully. In the return, a mock Roman triumph was celebrated in the streets of Alexandria. The parade through the city was a pastiche of Rome's most important military celebration. For the finale, the whole city was summoned to hear a very important political statement. Surrounded by Cleopatra and her children, Antony was about to put an end to his alliance with Octavian. He distributed kingdoms between his children: Alexander Helios was named king of Armenia and Parthia (not conquered yet), his twin Cleopatra Selene got Cyrenaica and Libya, and the young Ptolemy Philadelphus was awarded with Syria and Cilicia. As for Cleopatra, she was proclaimed Queen of Kings and Queen of Egypt, to rule with Caesarion (Ptolemy Caesar, son of Julius Caesar), King of Kings and King of Egypt. Most important of all, Caesarion was declared legitimate son and heir of Julius Caesar. These proclamations were known as the Donations of Alexandria and caused a fatal breach in Antony's relations with Rome.

Distributing insignificant lands among the children of Cleopatra was not a peace move, but it was not a serious problem either. What did seriously threaten Octavian's political position, however, was the acknowledgment of Caesarion as legitimate and heir to Julius Caesar's name. Octavian's base of power was his link with Caesar through adoption, which granted him much-needed popularity and loyalty of the legions. To see this convenient situation attacked by a child sired by the richest woman in the world was something Octavian could not accept. The triumvirate expired in the last day of 33 BC and was not renewed. Another civil war was beginning.

During 33 and 32 BC, a propaganda war was fought in the political arena of Rome, with accusations flying between sides. Antony (in Egypt) divorced Octavia and accused Octavian of being a social upstart, of usurping power, and of forging the adoption papers by Julius Caesar. Octavian responded with treason charges: of illegally keeping provinces that should be given to other men by lots, as was Rome's tradition, and of starting wars against foreign nations (Armenia and Parthia) without the consent of the senate. Antony was also held responsible for Sextus Pompeius execution with no trial. In 32 BC, both consuls (Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and Gaius Sosius) and a third of the senate abandoned Rome to meet Antony and Cleopatra in Greece.

In 31 BC, the war started. Octavian's loyal and talented general Agrippa captured the Greek city and naval port of Methone, loyal to Antony. The enormous popularity of Octavian with the legions secured the defection of the provinces of Cyrenaica and Greece to his side. On September 2, the naval battle of Actium took place. Antony and Cleopatra's navy was destroyed, and they were forced to escape to Egypt.

Octavian, now close to absolute power, did not intend to give them rest. In August 30 BC, assisted by Agrippa, he invaded Egypt. With no other refuge to escape to, Antony committed suicide. A few days later, Cleopatra herself followed his example.

With the death of Antony, Octavian became uncontested ruler of Rome: no one else attempted to take power from him. In the following years, Octavian, known as Augustus Caesar after 27 BC, managed to accumulate in his person all administrative, political, and military offices. During his life, the Roman Republic was not officially ended. Many date the beginning of the Roman Empire to the battle of Actium; however, the Empire can also be considered to date from the death of Augustus in 14 AD, with the succession of Tiberius.

Antony's marriages and descendants

1. Marriage to Fadia

2. Marriage to Antonia Hybrida (his direct cousin)

3. Marriage to Fulvia

o Marcus Antonius Antyllus, executed by Octavian in 31 BC

o Iullus Antonius, married Claudia Marcella Major, daughter of Octavia

4. Marriage to Octavia

o Antonia Major, married Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus

o Antonia Minor, married Drusus, the son of Livia

5. Children with Cleopatra

o The twins

? Alexander Helios, the sun

? Cleopatra Selene, the moon, married King Juba II of Numidia (and, later, Mauretania)

o Ptolemy Philadelphus.Chronology

• 83 BC—born in Rome

• 54–50 BC—joins Caesar's staff in Gaul and fights in the Gallic wars

• 50 BC—tribune of the plebians

• 48 BC—master of the horse

• 47 BC—ruinous administration of Italy: political exile

• 44 BC—consul with Caesar

• 43 BC—forms the second triumvirate with Octavian and Lepidus

• 42 BC—defeats Cassius and Brutus; travels through the East

• 41 BC—meets Cleopatra

• 40 BC—returns to Rome, marries Octavia; treaty of Brundisium

• 38 BC—treaty of Tarentum: triumvirate renewed until 33 BC

• 36 BC—disastrous campaign against the Parthians

• 35 BC—conquers Armenia

• 34 BC—the donations of Alexandria

• 33 BC—end of the triumvirate

• 32 BC—exchange of accusations between Octavian and Antony

• 31 BC—battle of Actium

• 30 BC—Antony and Cleopatra commit suicide• Born: 83 B.C. • Birthplace: Rome

• Died: 30 B.C. (suicide)

• Best Known As: Cleopatra's ill-fated loverLatin name: Marcus Antonius

Antony was a daring general in the army of Julius Caesar who rose to become one of Caesar's closest colleagues. After Caesar was assassinated in 44 B.C., Antony jumped into the struggle for control of Rome. (At the funeral of Caesar he spoke out strongly against the assassins; William Shakespeare later dramatized this moment in the play Julius Caesar, with the famous oration beginning "Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears.") Antony joined forces with Caesar's adopted heir Octavian to purge Rome of their common enemies. They formed the so-called Second Triumvirate with general Marcus Lepidus and divided the empire, with Antony being given control of Egypt. There he met and became the lover of the Egyptian queen Cleopatra. Their meeting, with Cleopatra dressed as the love goddess Venus and arriving on a lavishly decorated barge, is a famous story recorded by Plutarch and others. Antony and Cleopatra joined forces and the triumvirate dissolved. At the battle of Actium in 31 B.C. the naval forces of Antony and Cleopatra were routed by those of Octavian. (Cleopatra fled the scene while the battle was still underway, and Antony followed; their departure is often regarded as one of naval history's great blunders.) A year later, with Octavian's forces nearing Alexandria, Antony committed suicide by falling on his sword. Cleopatra followed suit (allegedly killing herself with the self-inflicted bite of a poisonous snake) and Octavian was left in final control of Egypt and Rome. Antony's life and tragic end was immortalized by Shakespeare in his play Antony and Cleopatra.

Marc Antony's name is sometimes modernized to "Marc Anthony," and he is sometimes called simply "Antony"... Marc Anthony is also the name of a popular modern salsa musician... Much of what we know about Antony's character comes from his description by Plutarch in Parallel Lives of Famous Greeks and Romans, otherwise known as Plutarch's Lives... Cleopatra had been a lover of Julius Caesar before becoming the lover of Antony... Among those killed by Antony in his purge of Rome was the popular statesman and orator Cicero.